WSC 2023-2024, Conference 15, Case 2

Signalment:

40-day-old male Cobb broilers (Gallus gallus domesticus)

History:

Two male 40-day-old Cobb broilers from a commercial farm in Victoria were submitted for necropsy and diagnostic work up following euthanasia by cervical dislocation. The farm was culling 200 birds per shed (approximately 0.5% of birds) at the time. The submitting veterinarian reported that the birds have normal mentation but have paresis or paralysis and a characteristic posture, sitting back on their hocks with legs extended in front of them and wing walking. Post mortem examination of one bird by the submitting veterinarian showed a small bursa and femoral head necrosis.

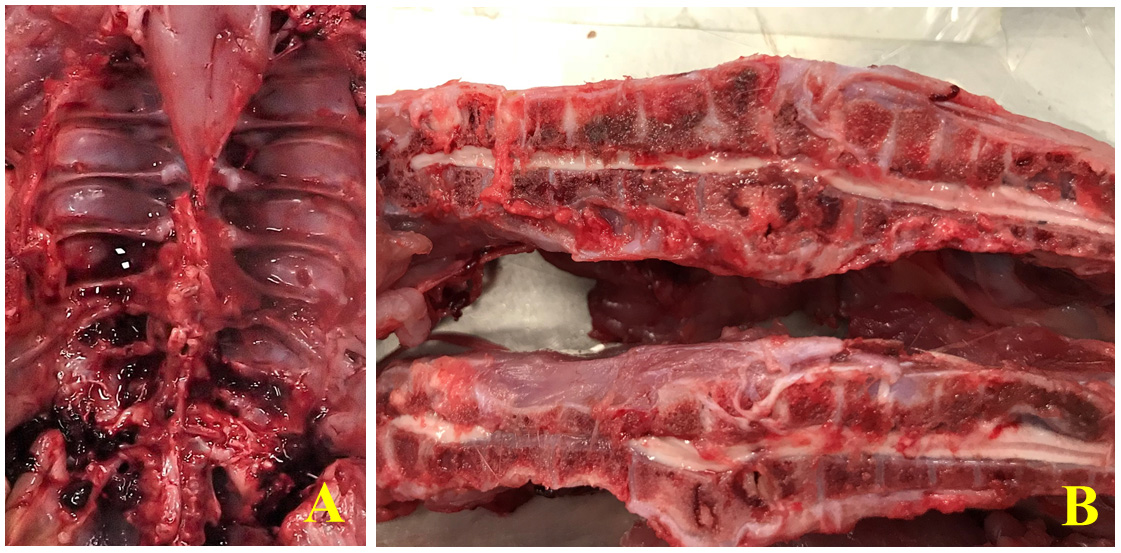

Gross Pathology:

Both birds examined were well-preserved and in good body condition. The free thoracic vertebra was expanded and effaced by a yellow-tan multinodular mass that appeared to be inflammatory, associated with a presumably pathologic fracture, and to focally and severely compress the spinal cord. The bisected T4-T5 vertebral sections of both subjects revealed focal red discolouration of the hypaxial muscles surrounding the cord compression focus. The left femoral head was diffusely, markedly red on the articular surface and appeared enlarged compared to the right in both birds. There was some soiling (brown, soft material) of the vent of one bird. The bursa and other organs, including other vertebrae examined, showed no noteworthy changes grossly.

Laboratory Results:

Aerobic culture (vertebral abscess swabs) yielded a lightly contaminated growth, with Enterococcus cecorum isolated as the predominant organism.

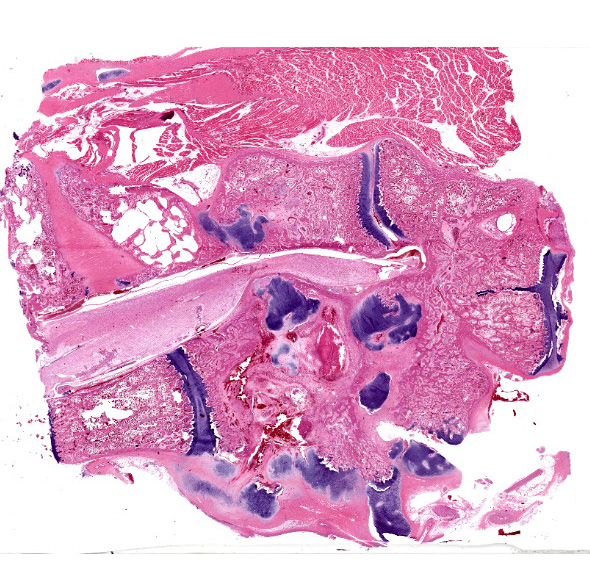

Microscopic Description:

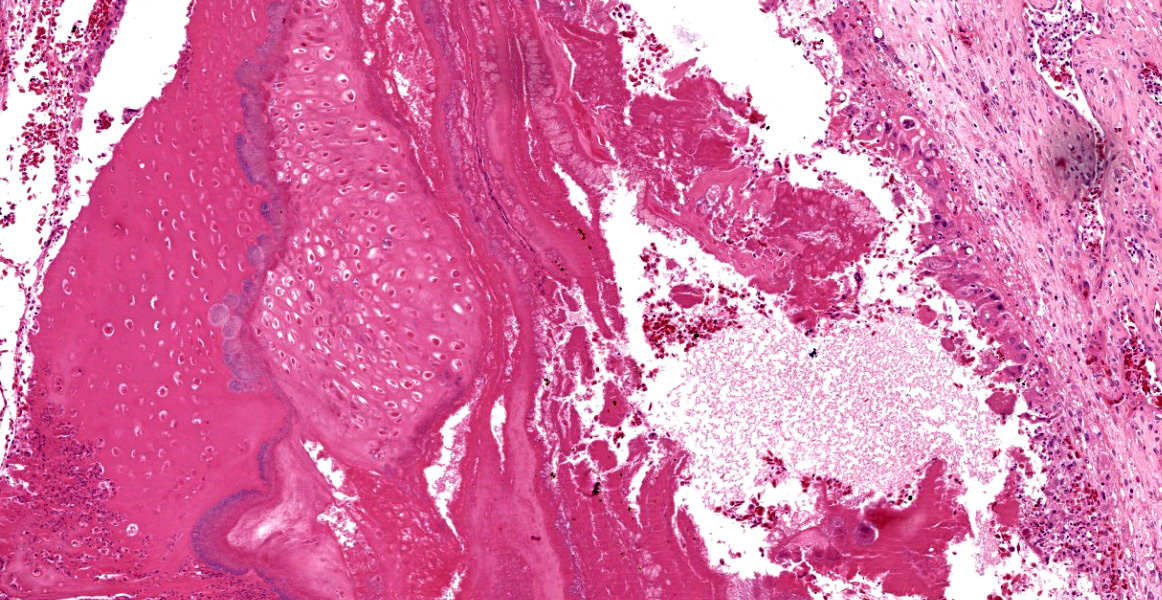

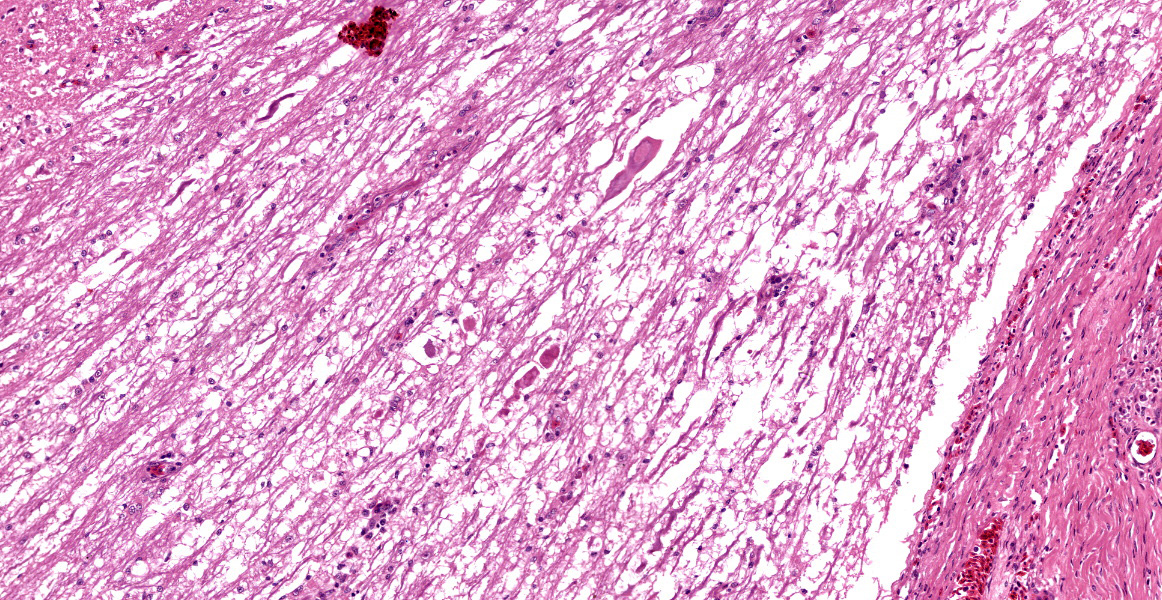

Histologically, the femur, bursa, and other organs apart from the free thoracic vertebra (FTV) showed no noteworthy changes. In both birds, covering over 70% of the sagittal plane examined, the architecture of the vertebral bodies of T4/T5 was largely obliterated and replaced by extensive multinodular callus formation. The spinal cord was severely compressed at this level by the callus. There was mild to moderate Wallerian degeneration characterised by vacuolation of the adjacent white matter, with spheroids, degenerate macrophages, or axonal debris noted in some vacuoles, these changes interpreted as confirming that the compression was real, as opposed to a plane of section artifact. Within the vertebra, there was extensive necrosis, osteolysis, oedema, fibrin deposition, haemorrhage and moderate infiltration by heterophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Multifocally within these areas of necrosis and remodelling there were large numbers of small monomorphic bacterial aggregates (mainly cocci). On Gram stained sections, these were shown to be gram positive cocci.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

T4/T5 vertebrae: Spondylitis, severe, heterophilic, lymphoplasmacytic, haemorrhagic, necrotising with extensive remodelling, pathologic fracture, callus formation and focal spinal cord compression.

Contributor’s Comment:

The colloquial term “kinky back” is occasionally used in practice to refer to Enterococcal spondylitis of the T4/T5 vertebrae. Enterococcus cecorum is a gram-positive enteric commensal of poultry; however, strains of E. cecorum causing outbreaks have significantly smaller genomes than commensal E. cecorum.1 Pathogenic E. cecorum has also been reported to cause disease in Pekin ducklings and pigeons. The posture of the broilers (sitting back on their hocks) is characteristic, although not pathognomonic of this condition. Wing walking is used for locomotion, and this also limits their access to food. An interesting feature of this condition is the characteristic lesion localisation at the free thoracic vertebra (FTV). The FTV has greater weight-bearing articulations compared to the adjacent notarium and synsacrum, potentially predisposing it to infection with pathogenic E. cecorum.

Another condition that is also referred to as “kinky back” is spondylolisthesis caused by subluxation of the fourth thoracic vertebra (T4). Ventral displacement of the cranial end of T4 also results in compression of the spinal cord via narrowing of the vertebral canal (dorsal projection of its posterior extremity). The aetiology of spondylolisthesis is primarily genetic, as opposed to bacterial as is the case for enterococcal spondylitis, but the occurrence is influenced by increased growth rate.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Biosciences and Australian Pacific Centre for Animal Health Melbourne Veterinary School

The University of Melbourne

Werribee, Victoria, Australia

unimelb.edu.au

JPC Diagnosis:

Vertebrae: Spondylitis, necrotizing, focally extensive, severe, with pathologic fracture, callus, and focal spinal cord compression.

JPC Comment:

This case provides an excellent example of a classic entity of poultry. As the contributor notes, one of the curiosities of Enterococcal spondylitis (ES) is its tropism for the free thoracic vertebra (FTV). Cranial to the FTV, the thoracic vertebrae are fused into the notarium via synchondrosis rather than with synovial articulations and intervertebral discs, as in mammals.1 Caudal to the FTV, the caudal thoracic vertebrae, lumbosacral vertebrae, and the pelvic bones are similary fused into the synsacrum, leaving the FTV as the only vertebra in the thoracolumbar column to have weight bearing articulations.1 This anatomic oddity places substantial mechanical stress on the FTV as it transfers body weight to the hips and hind limb, perhaps predisposing the FTV to injury and to subsequent infection with pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum.1

By the time clinical signs are evident, typically in weeks 4-6 of life, spinal lesions are already well developed, with histologic evidence of chronic infection.1 A recent study evaluated lesion development in ES during the first four weeks of life, when affected chickens are incubating subclinical disease. The study found that the first step in the development of ES is the colonization of the gut by pathogenic E. cecorum species within the first week of life. This is in contrast to commensal E. cecorum, which arrives in the chicken gut around 3 weeks of age. The authors speculate that the ability to colonize the gut early in life may be a key virulence event, conveying a competitive advantage that allows pathogenic bacteria to disseminate throughout a flock.1

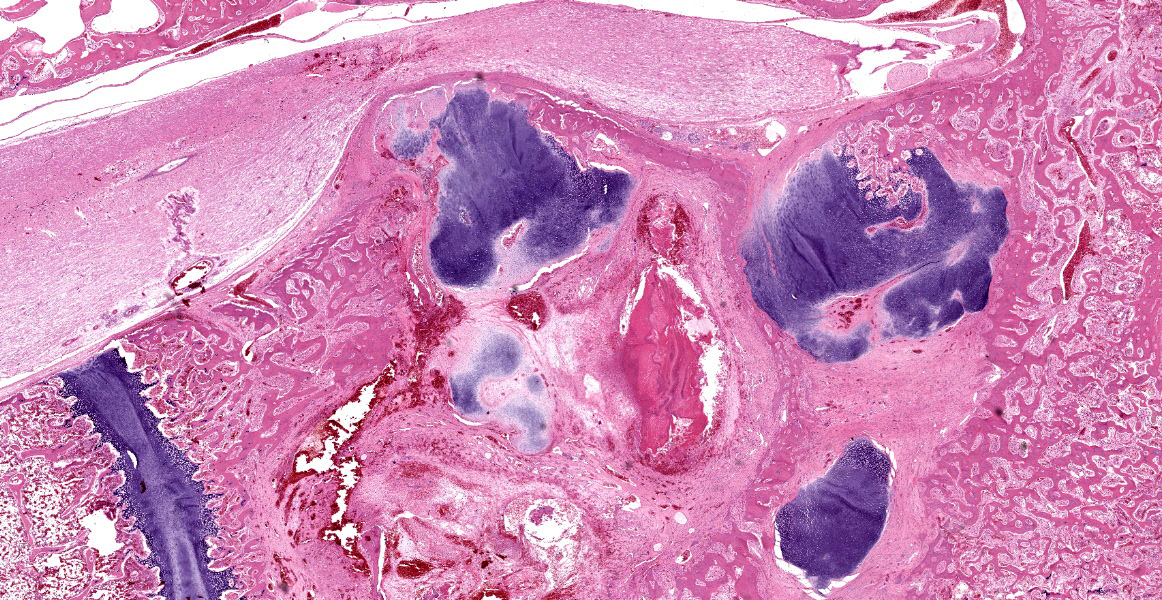

A second likely step in ES pathogenesis is the development of osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD) lesions in the FTV.1 OCD lesions progress through a stereotypical sequence, thought to be initiated and driven by vascular disturbances or increased type II collagen production.2 The earliest changes observable in the cartilage consist of a poorly defined focus of eosinophilia and hypocellularity in the articular cartilage, termed osteochondrosis latens, which may extend to the subchondral bone.1,2 These areas may remain stable, or may progress to osteochondrosis manifesta, characterized by areas of cartilage retention in the ossification zone.1 Finally, fully-fledged OCD lesions are characterized by clefts in the hyaline cartilage which may communicate with the joint space or extend into subchondral bone.1,2

Large cartilaginous clefts are the hallmark lesion of OCD and are readily identifiable in affected birds as early as 1 week of age; these clefts are variably filled with fibrin, erythrocytes, and, in some birds, bacterial cocci consistent with E. cecorum.1 These lesions progress over the next two weeks with an influx of heterophilic and histiocytic inflammation targeting these cocci-filled cartilaginous clefts.1 Continued progression leads to the bone remodeling and spinal cord compression that comprise the stereotypical ES lesion.1

It remains unclear why cartilage clefting predisposes chickens to ES lesions. One theory is that hemorrhage into the cartilage clefts introduces bacteremic, pathogenic E. cecorum to the site of injury and, once there, the devitalized cartilage provides a favorable niche for bacterial persistence and proliferation. Whatever the reason, the unique anatomic features of the weight-bearing FTV, which articulates through epiphyseal cartilage without the benefit of joint capsules or intervertebral discs, makes it uniquely susceptible to trauma, and the FTV is the only location within the vertebral column where OCD lesions and subsequent E. cecorum colonization occur.1

Dr. Craig discussed the alternating layers of bacteria and cartilage within the lesion. These layers provide histologic support for the tidy pathogenic narrative discussed above. Without engaging in excessive flights of fancy, it is easy to imagine the successive rounds of cartilage clefting and bacterial colonization that result in this spectacular ES lesion. Dr. Craig also noted several basophilic, circular areas within the tissue that represent residual mineral left over from the decalcification process. These artifacts can be misinterpreted as mast cells, macrophages, or other histologic features, and can be avoided by copious rinsing of tissue after decalcification and prior to further processing.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis focused initially on whether to include the various inflammatory cells present in the lesion. Conference participants felt that the chronic nature of the lesion, evidenced by callous formation, implied the existence of a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and made the inclusion of this histologic feature superfluous. Partipants also decided to omit the bacterial cocci which, while confirmed with Gram stain, were not convincingly evident to all participants based on H&E evaluation alone.

References:

- Borst LB, Suyemoto MM, Sarsour AH, et al. Pathogenesis of enterococcal spondylitis caused by Enterococcus cecorum in broiler chickens. Vet Pathol. 2017;54:61-73.

- Olstad K, Ekman S, Carlson CS. An update on the pathogenesis of osteochondrosis. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(5):785-802.