Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 11

December 6th, 2017

CASE IV: WSC 2017-2018 Rhinoceros (JPC 4101227).

Signalment: 48-year-old female, southern white (Ceratotherium simum), rhinoceros.

History: This 48-year-old, female southern white rhinoceros was housed at a zoologic institution. The animal was humanely euthanized due to quality of life concerns including progressive right forelimb lameness that had become poorly responsive to medical management.

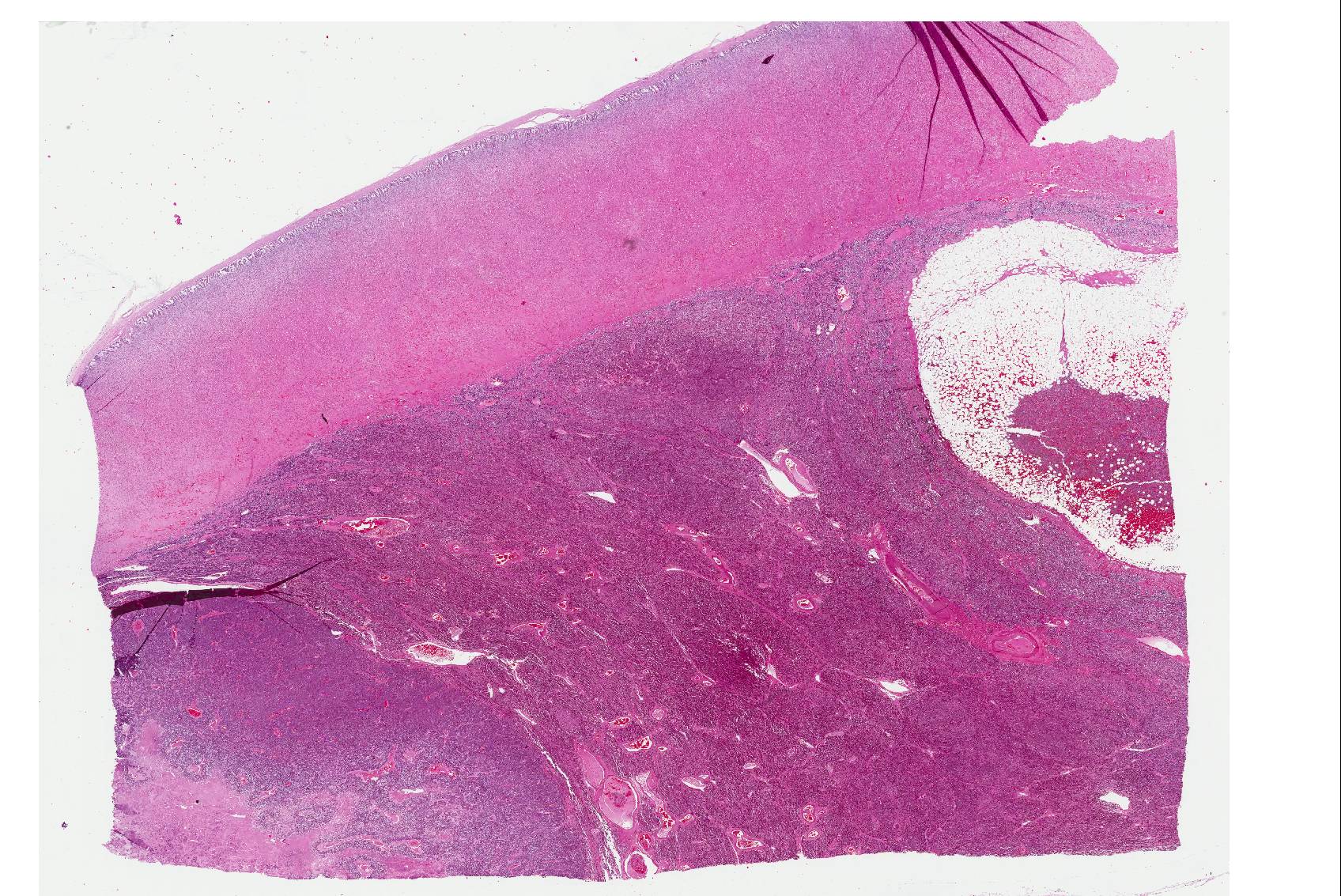

Gross Pathology: At necropsy, both adrenal medullas were markedly enlarged relative to the adrenal cortices (cortex: medulla thickness ratio approximately 1:8). The right adrenal medulla contained a well demarcated, 4cm diameter, slightly firm, round, tan to pink mass that focally compressed the adjacent cortex. Also present within the right medulla, were two, well demarcated, 1-1.5cm diameter, soft, ovoid masses that were mottled light tan to dark red. Approximately 90% of normal tissue in the left adrenal medulla was replaced by an irregular, multilobulated, approximately 8cm diameter mass that was light tan and soft, with multiple areas that were dark red, shiny, and friable.

Additional gross findings in this animal included severe osteoarthritis affecting all appendicular joints examined, multiple uterine leiomyomas, sclerotic kidneys with numerous cysts, severe dental disease, and a pedunculated mesenteric lipoma.

Laboratory results:

None submitted.

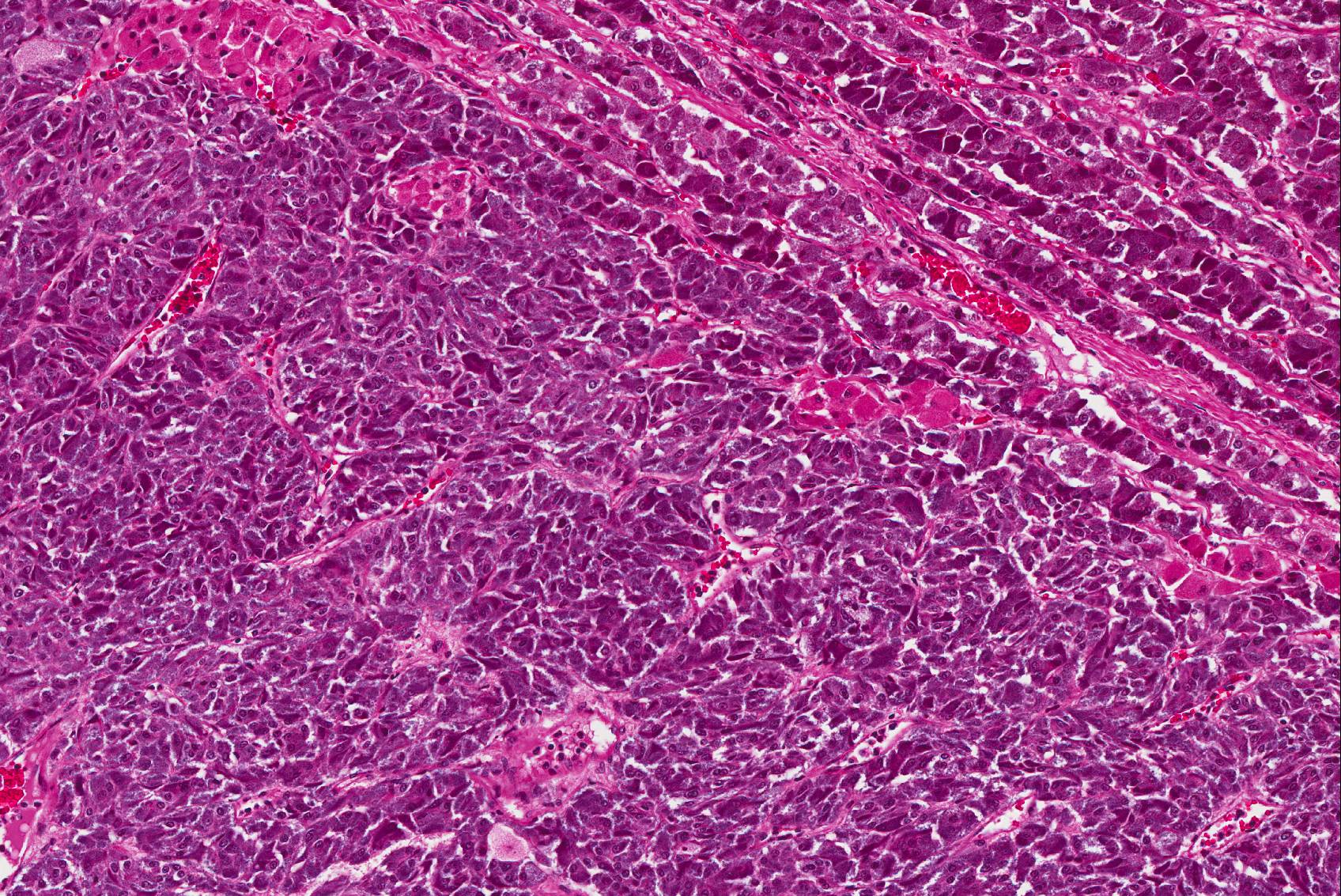

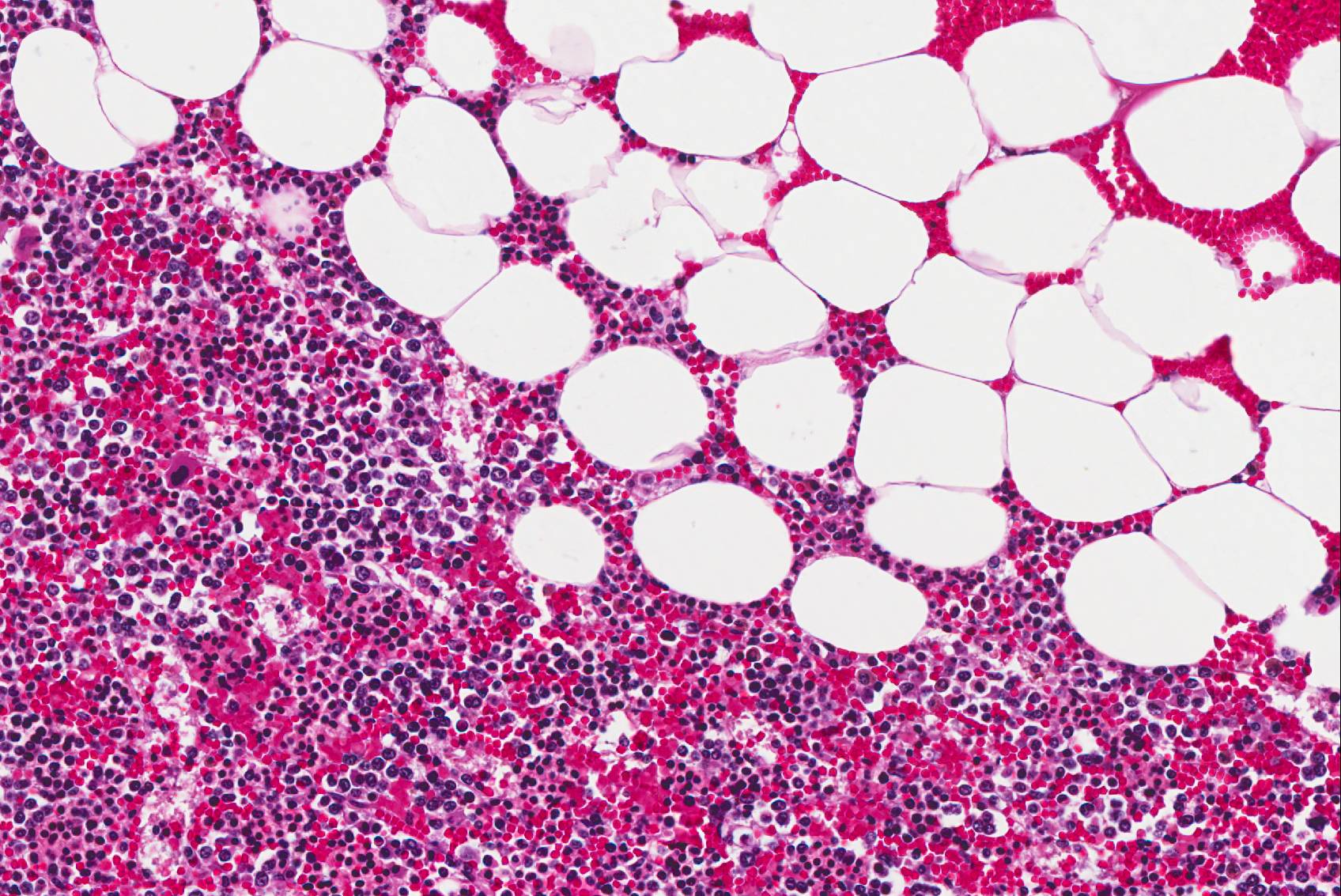

Microscopic Description: The tissue consists of a single section from the right adrenal gland. Within the medulla are two, distinct, neoplastic masses that are well-demarcated, partially encapsulated, and variably compress the adjacent parenchyma. One mass is composed of mature adipocytes and hematopoietic precursor cells arranged in sheets on a scant fibrovascular stroma. All three blood cell lineages (erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid) are represented. There are also abundant mature red blood cells admixed with small amounts of eosinophilic proteinaceous fluid and scattered, golden to dark brown pigment-laden macrophages. Cellular atypia is minimal and mitotic figures are rare in this mass (<1 per 10 HPF). The second mass is composed of neoplastic cells arranged in nests and packets on a highly-vascularized fibrous stroma. Neoplastic cells frequently palisade around blood vessels (pseudorosette formation). Neoplastic cells are polygonal with distinct cell borders, abundant finely granular, basophilic cytoplasm, and round nuclei with finely stippled chromatin and one distinct nucleolus. There is minimal anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Mitoses average less than 1 per 10 HPF. Affecting approximately 30% of the mass is an area of central coagulation necrosis and mineralization. Multiple medium-caliber arteries within the medulla contain intraluminal aggregates of neoplastic cells (vascular invasion).

Additional note: The large mass in the left adrenal medulla was histologically identical to the first mass described above, with areas of hematopoietic precursor cells and mature adipose tissue.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

- Adrenal gland, pheochromocytoma, unilateral, with necrosis and vascular invasion

- Adrenal gland, myelolipoma, multifocal, bilateral

- Adrenal gland, medullary hyperplasia, diffuse, unilateral, marked (gross diagnosis)

Contributor’s Comment: This case documents the presence of bilateral adrenal myelolipoma with concurrent unilateral pheochromocytoma and adrenal medullary hyperplasia in a rare species.

Myelolipomas are benign, hormonally inactive, extra-marrow tumors composed of mature adipose tissue and hematopoietic elements. While myelolipomas are not uncommon in humans, they are relatively rare in veterinary species. Reports of myelolipomas in animals are limited to dogs,20 domestic and non-domestic cats (most notably cheetahs),2 rodents,3,18 opossums,13 and Old and New World monkeys.9 In animals, they are most commonly reported in the liver, spleen, and adrenal cortex; additional sites include the subcutis (birds),7 extradural space (dog),11 and eye (dog).21

The etiology of adrenal myelolipomas remains unclear; however there are three proposed mechanisms of development: (1) distant seeding of bone marrow via hematogenous emboli, (2) maturation of embryonic mesenchymal rests, and (3) metaplasia of the adrenal cortex due to chronic hormonal imbalance or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion.5 Support for hypothesis #3 comes from controlled experiments in rats, which demonstrated that prolonged administration of testosterone and ACTH induced transformation of the inner zona fasciculata to tissue resembling bone marrow.19 Additionally, myelolipomas frequently occur in people concurrently suffering from Cushing’s disease, hypertension, diabetes and obesity, further suggesting a link with hormonal imbalance or chronic stress.6 Myelolipomas are rarely reported in conjunction with pheochromocytomas in both people22 and non-human primates.10

Pheochromocytomas are tumors of the chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla; these are the cells which synthesize and secrete catecholamines (norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine). They are the most common tumor of the adrenal medulla in animals, have been reported in a wide variety of mammals, and are best documented in humans, dogs, bulls, and rats.15 There is a single previous report of pheochromocytoma a white rhinoceros.1 While most pheochromocytomas in animals are reportedly non-functional,14 functional tumors can be associated with hypertension and cardiomyopathy due to high circulating levels of catecholamines.4,24 The previous report of pheochromocytoma in a rhinoceros documented increased serum epinephrine and norepinephrine, as well as histologic changes consistent with systemic hypertension.1 Hormone levels were not tested in this animal, however medial hypertrophy of arteries and arterioles in multiple organs and a focally extensive area of myocardial fibrosis at the junction of the right and left ventricles, suggest that the pheochromocytoma may have been functional. Histologic grading of pheochromocytomas in humans is based on a scoring system (Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score) in which points are assigned for characteristics including vascular invasion, capsular invasion, local invasion, necrosis, mitoses, and nuclear pleomorphism.8 While vascular invasion and necrosis were observed in the present case, there was no evidence of local invasion or distant metastases.

Grossly, the right adrenal gland of this rhinoceros had a cortical to medullary thickness ratio of roughly 1:8, suggestive of generalized medullary hyperplasia and / or cortical atrophy. The ratio in the left adrenal gland was similar, but this may have been due to replacement and expansion of normal medullary tissue by the large myelolipoma. While normal ratios for white rhinos are not well established, a previous morphologic study reported that the medulla accounted for only 20% of the mass of the entire adrenal gland.14 Medullary hyperplasia in veterinary species can be associated with pheochromocytoma and multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN was not documented in this case).12

JPC Diagnosis:

- Adrenal gland: Pheochromocytoma, Southern white (Ceratotherium simum), rhinoceros.

- Adrenal gland: Myelolipoma.

Conference Comment: In prehistoric times, rhinoceroses were the most common large herbivores in North America, and today, they are one of the most primitive of the world’s large mammals. There are five species that exist in four genera: in Africa there are white (Ceratotherium simum) and black (Dicero bicornis) rhinos, in Asia there are Sumatran (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), Indian (Rhinoceros unicornis), and Javan (Rhinoceros sondaicus) rhinos. Of the five species, Sumatran are the most primitive and predate the wooly rhino (Coelodonta antiqitatis), now extinct, which inhabited northern Europe and Asia during the last Ice Age. In Africa, white rhinos prefer to live on flat terrain which short grasses and black rhinos live in areas with shrubs and young trees, these preferences are associated with their dietary requirements. Regardless, all species of rhino are hindgut fermenters with fast transit times who require regular access to water to cool off, keep their skin free of external parasites, and stay hydrated. Of the five species, white rhinos have the largest world population estimate at 20,143 (2012). The skin of a rhinoceros is extremely thick, with the white rhino’s skin reaching a thickness of five centimeters.11

In rhinoceroses, neoplasia is fairly uncommon. There have been reported cases of squamous cell carcinoma in white, black, and Indian rhinos as well as cutaneous melanoma in black and Indian rhinos. Rare cases of thyroid carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia have been reported in black rhinos.11

Myelolipomas are benign tumors that are most often encountered in the adrenal glands of cattle, nonhuman primates, and occasionally other species composed of aggregates of mature adipocytes, reactive fibroblasts, and myeloid and erythroid hematopoietic cells. Occasionally, fibroblasts undergo osseous differentiation and areas of osseous metaplasia occur within the tumor. These tumors are thought to originate from metaplastic transformation of adrenal cortical cells, although their exact origin in currently unknown.16,23

Pheochromocytomas are the most common neoplasm arising in the adrenal medulla of domestic animals, but are more frequent in cattle and dogs. Microscopically, they arise from the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla, are either unilateral or bilateral, and generally have abundant hemorrhage and necrosis. Macroscopically, the Henle chromaffin reaction can be used to detect the tumor using either potassium dichromate or iodate. When Zenker’s solution is applied to a flat surface of freshly cut tumor, there is oxidation of the catecholamines, and a dark brown pigment that forms within 20 minutes. Ultrastructurally, pheochromocytomas are composed of epinephrine secreting cells, norepinephrine secreting cells, or a combination of the two. The cells that secrete epinephrine have many low electron density granules with a narrow submembranous space. Conversely, the norepinephrine secreting cells have secretory granules with an eccentric electron dense core surrounded by a prominent submembranous space. With chronicity, tumor cells can grow into the caudal vena cava and form a neoplastic thrombus that can occlude drainage from caudal extremities. Metastasis occurs in about 50% of affected dogs to the liver, regional lymph nodes, spleen, and lungs. Since they are of endocrine origin, pheochromocytomas, when functional, can have serious systemic effects related to excessive catecholamine secretion such as: tachycardia, edema, cardiac hypertrophy, arteriolar sclerosis, and medial hyperplasia of arterioles.16,17

When discussing the adjacent “normal” adrenal medullary tissue, attendees reached an impasse. Some believed it to be truly hyperplastic, as evidenced by the gross images submitted by the contributor, while others believed that the thinned cortex was due to the mass of two neoplasms expanding the medulla and compressing and stretching the cortex. In short, it was difficult to make a definitive diagnosis of medullary hyperplasia with the single slide available to conference participants; however, if the contributor’s other sections of the medulla revealed increased amounts of normal medullary tissue histologically, we support the contributor’s gross diagnosis of medullary hyperplasia.

Contributing Institution:

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Department of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/mcp/

References:

- Bertelsen MF, Steele SL, Grondahl C, Baandrup U. Pheochromocytoma in a white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2011;42(3):521-523.

- Cardy RH, Bostrom RE. Multiple splenic myelolipomas in a cheetah. Veterinary Pathology. 1968;15:556-558.

- Dixon D, Yoshitomi K, Boorman G, Maronpot RR. "Lipomatous" lesions of unknown cellular origin in the liver of B6C3F1 mice. Veterinary Pathology. 1994;31:173-182.

- Edmondson EF, Bright JM, Halsey CH, Ehrhart EJ. Pathologic and cardiovascular characterization of pheochromocytoma-associated cardiomyopathy in dogs. Vet Pathol. 2015;52(2):338-343.

- Ishay A, Dharan M, Luboshitzky R. Combined adrenal myelolipoma and medullary hyperplasia. Horm Res. 2004;62(1):23-26.

- Khater N, Khauli R. Myelolipomas and other fatty tumours of the adrenals. Arab J Urol. 2011;9(4):259-265.

- Latimer KS, Rakich PM. Subcutaneous and hepatic myelolipomas in four exotic birds. Veterinary Pathology. 1995;32:84-87.

- LDR T. Pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland scaled score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2002;26(5):551-566.

- Lowenstine LJ, McManamon R, Terio KA. Comparative pathology of aging great apes: Bonobos, Chimpanzees, Gorillas, and Orangutans. Vet Pathol. 2016;53(2):250-276.

- Miller AD, Masek-Hammerman K, Dalecki K, Mansfield KG, Westmoreland SV. Histologic and immunohistochemical characterization of pheochromocytoma in 6 cotton-top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus). Vet Pathol. 2009;46(6):1221-1229.

- Miller MA, Buss PE. Rhinoceridae (rhinoceroses). In: Miller RE, Fowler ME, eds. Fowler’s Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 8. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:538-539, 544.

- Miller MA. Endocrine system. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017:709.

- Newman SJ, Inzana K, Chickering W. Extradural myelolipoma in a dog. Journal of veterinary diagnostic investigation. 2000;12:71-74.

- Peng K, Song H, Liu H, Zhang J, Lu Z, Liu Z, et al. Histologic study of the adrenal gland of African White Rhinoceros. Pakistan Veterinary Journal. 2011;32(3):394-397.

- Pope JP, Donnell RL. Spontaneous neoplasms in captive Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana): a retrospective case series (1989-2014) and review of the literature. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2017;29(3):1-7.

- Rosol TJ, Grone A. Endocrine glands. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 3. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:343-344, 349-352.

- Rosol TJ, Meuten DJ. Tumors of the endocrine glands. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. Ames, IA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2017:787-791.

- Schardein JL, Fitzgerald JE, Kaump DH. Spontaneous tumors in holtzman-source rats of various ages. Veterinary Pathology. 1968;5:238-252.

- Selye H, Stone H: Hormonally induced transformation of adrenal into myeloid tissue. American Journal of Pathology. 1950;26(2):211-233.

- Spangler WL, Culbertson MR, Kass PH: Primary mesenchymal (nonangiomatous/nonlymphomatous) neoplasms occurring in the canine spleen: anatomic classification, immunohistochemistry, and mitotic activity correlated with patient survival. Veterinary Pathology. 1994;31:37-47.

- Storms G, Janssens G. Intraocular myelolipoma in a dog. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2013;16:183-187.

- Ukimura O, Inui E, Ochiai A, Kojima M, Watanabe H. Combined adrenal myelolipoma and pheochromocytoma. Journal of Urology. 1995;154:

- Valli VE, Bienzle D, Meuten DJ. Tumors of the hemolymphatic system. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. Ames, IA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2017:317-318.

- Zuber SM, Kantorovich V, Pacak K. Hypertension in pheochromocytoma: characteristics and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(2):295-311, vii.