Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

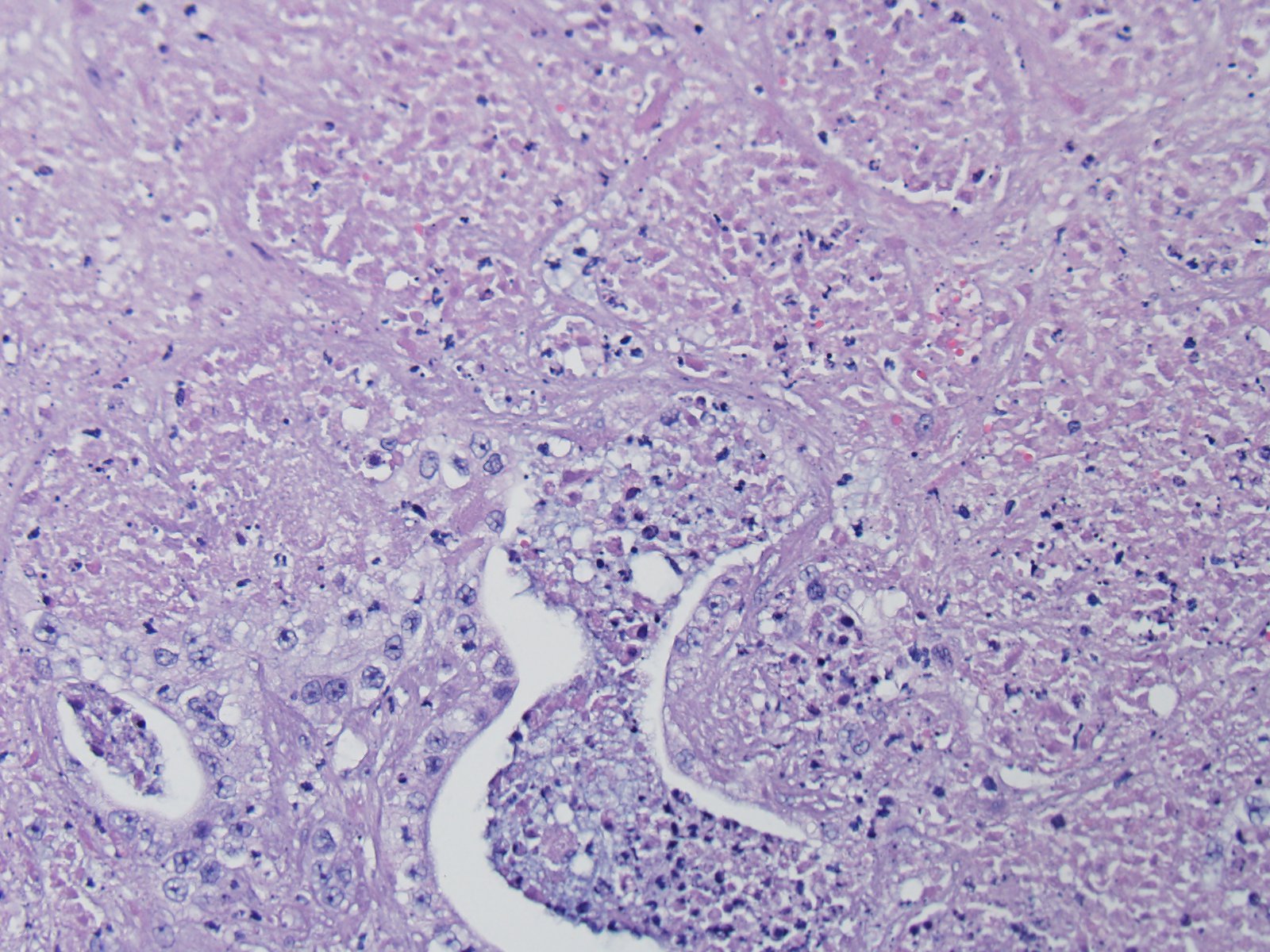

Within the adjacent remaining parenchyma, portal regions are expanded by moderate proliferations of lymphocytes & plasma cells, with bile duct proliferation, and periductular fibrosis. Some bile ducts are lined by attenuated epithelium and contain luminal or periductal neutrophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Although primary hepatobiliary tumors are rare in cats, cholangiocellular carcinoma represents the most common non-hematopoietic, hepatic malignancy in this species.1 This is a locally aggressive neoplasm with a high metastatic potential, and metastases are documented in up to 80% of necropsy cases.8 Extrahepatic metastasis is common, especially to cranial abdominal lymph nodes and lung, and seeding of tumor into the abdominal cavity is not uncommon, with lesions extending throughout the mesentery and visceral peritoneal surfaces.11

In cats, cholangiocellular carcinomas are typically found in animals of 9 years of age and older.1 There are no breed predilections, and although there are some suggestions that this tumor is more commonly diagnosed in male cats,1 other studies do not demonstrate such a gender difference.6 The prognosis is poor, with a life expectancy of less than 6 months.6

As compared with cats with benign tumors of the biliary tract, cats with cholangiocellular carcinoma are more likely to exhibit clinical signs, and lethargy, anorexia, and vomiting are most commonly reported.1 Upon physical examination, the most common finding is the presence of a cranial abdominal mass or hepatomegaly, while ascites and icterus are less common.1

Hematologic and biochemical profiles are often nonspecific.1 Leukocytosis is so-metimes reported, and alanine amino-transferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bilirubin levels may be elevated.6

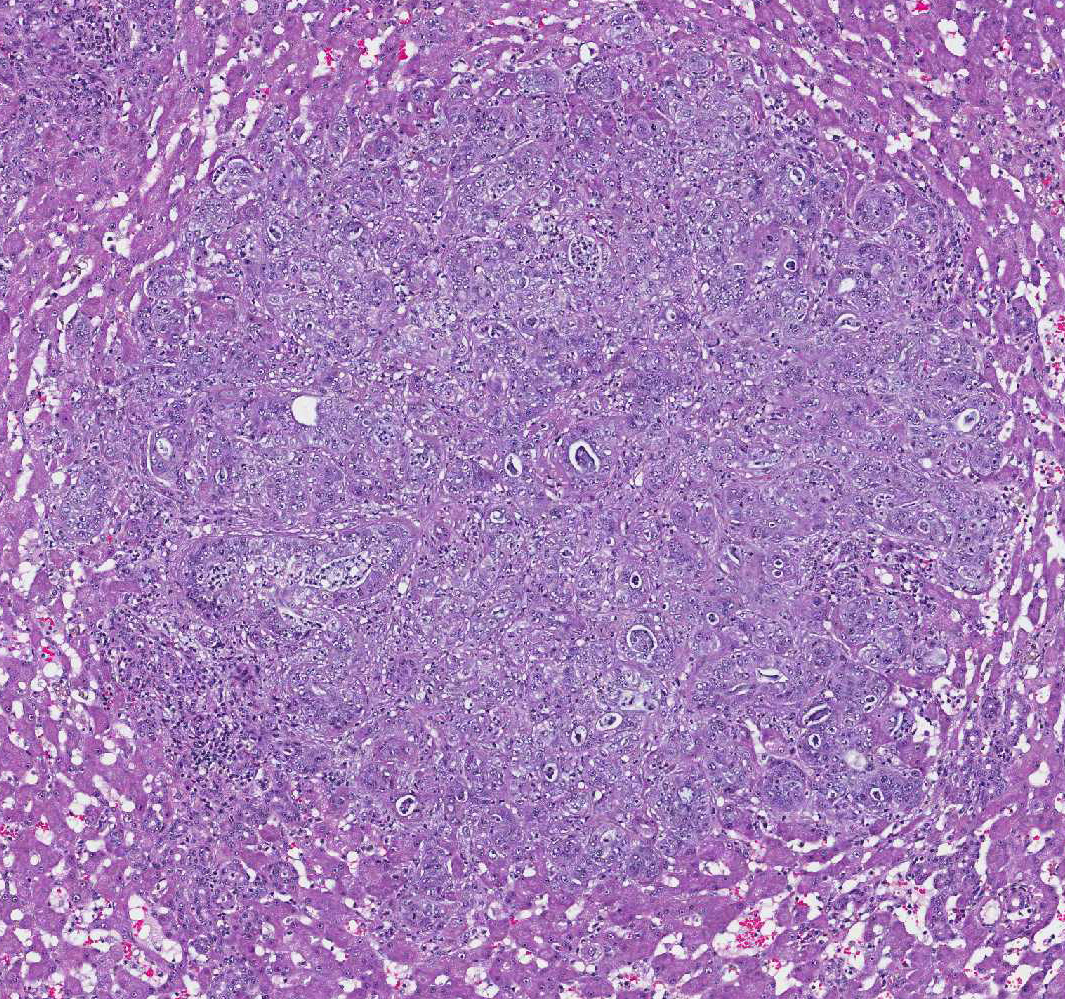

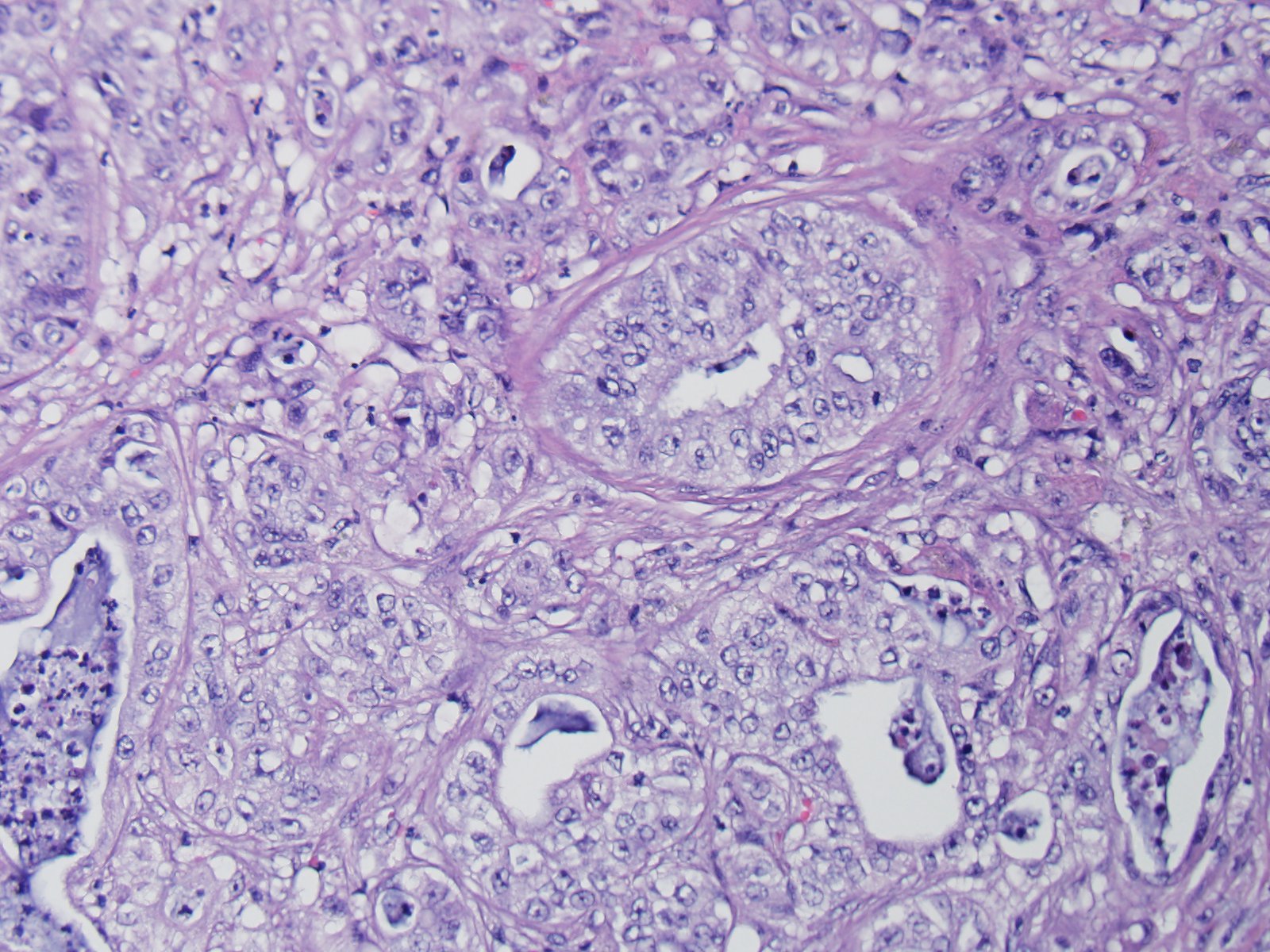

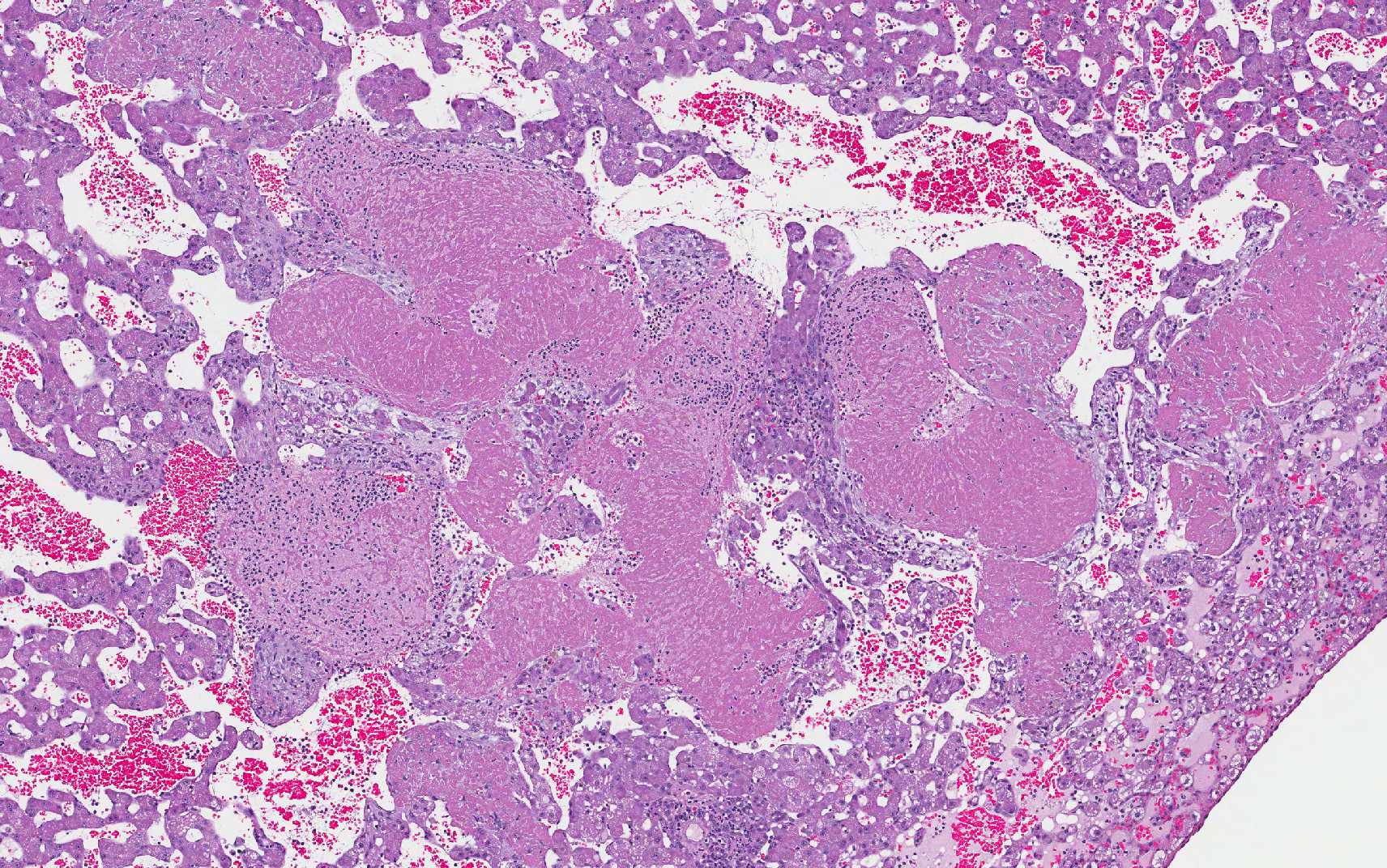

Microscopically, these tumors are usually distinctly adenocarcinomatous, comprising proliferations of cells that differentiate toward biliary epithelial cells, and form acini, tubules, and papillary projections. More poorly differentiated forms may be composed of solid epithelial proliferations, with or without the formation of islands, cords, or packets of cells, and foci of squamous differentiation. Numerous mitotic figures are present. A variable connective tissue stroma is present, often with marked collagen deposition, the so-called scirrhous response. Areas of necrosis are also common.7,11

Paraneoplastic alopecia has also been associated with cholangiocellular carcinoma, as well as pancreatic adenocarcinoma in cats. This presents as bilaterally symmetrical alopecia of the ventrum and limbs, sometimes with a shiny appearance to the alopecic skin. Histologically, skin changes comprise follicular and adnexal atrophy with hypoplasia of the stratum corneum.9

In people, cholangiocellular

carcinoma is the second most common hepatic malignancy after hepatocellular

carcinoma, accounting for more than 7% of cancer deaths throughout the world.

In the United States, it accounts for 3% of all cancer deaths, and its

prevalence is highest in Hispanics. Although most cholangiocellular carcinomas

in the western world arise without evidence of antecedent disease, chronic

hepatobiliary inflammatory conditions can predispose patients to development of

these tumors. The incidence rates of this malignancy are highest in Southeast

Asia, where a major risk factor is chronic infection of the biliary tract with

the liver fluke Opisthorchis sinensis. Additional predisposing risk

factors for development of cholangiocellular carcinoma in people, include:

primary sclerosing cholangitis; infection with hepatitis B or C; and congenital

diseases of the biliary tract, such as choledochal cysts or Carolis syndrome.4,5

However, no definitive association between inflammatory hep-atobiliary disease,

or other antecedent conditions, has been established in cats.

JPC Diagnosis:

2. Liver: Cholangiohepatitis, suppurative, multifocal, severe, with septic thrombi and telangiectasis.

Conference Comment:

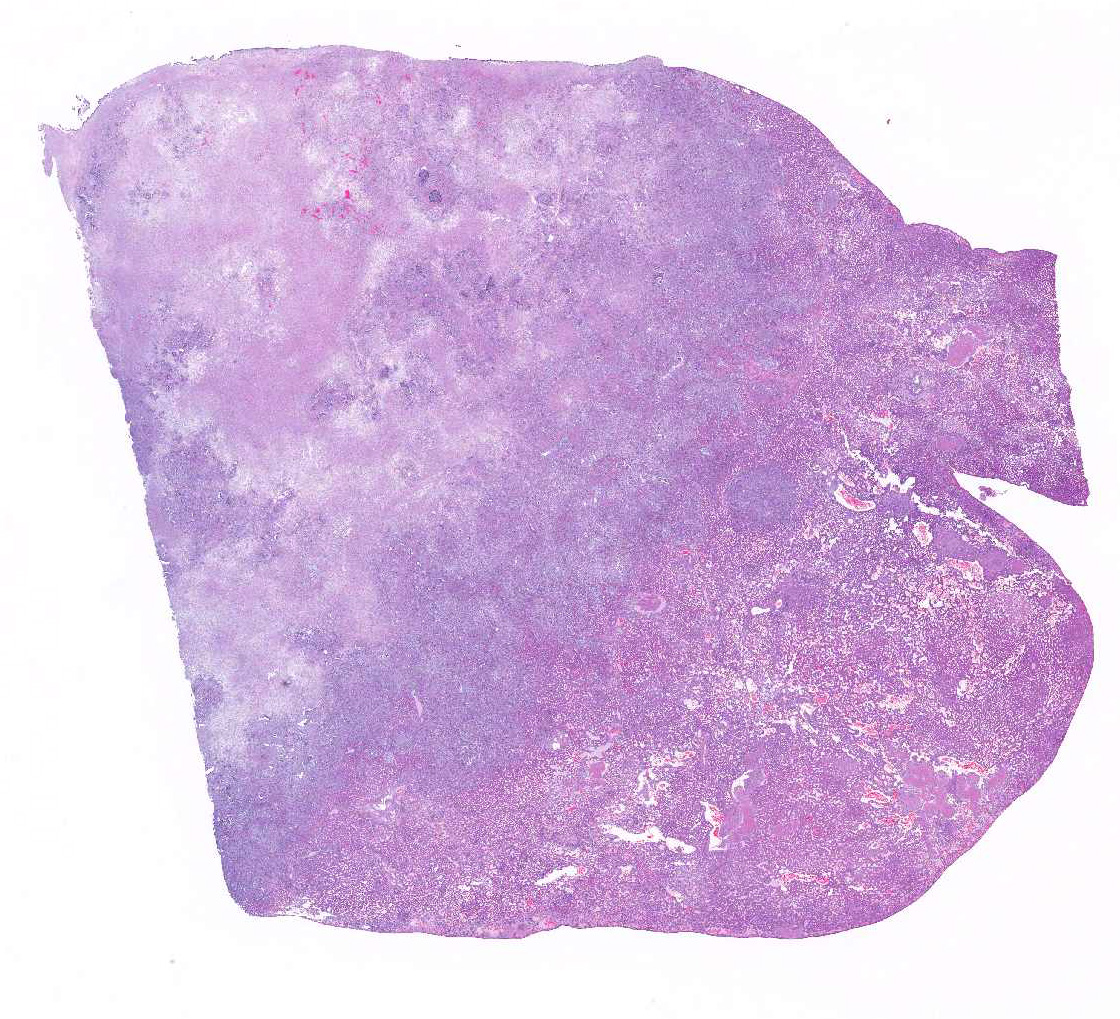

In this slide, the lobular hepatic

architecture is approximately 75% effaced.

Concentric fibrosis surrounding bile ducts is a prominent feature, and the

moderator commented this feature is secondary to cholestasis, and neutrophilic

cholangitis is, in turn, the result of biliary stasis.

Fibrin thrombi within sinusoids and blood vessels contain enmeshed epithelioid macrophages and other inflammatory cells. In this slide, large areas of sinusoidal dilation border fibrin thrombi. These areas of dilation may represent local blood flow change or, in the normal liver, would often be interpreted as foci of telangiectasis, a common histologic finding in the liver of the cat.

Additionally, two important diagnostic features in this case include the scirrhous reaction and mucous within ducts / tubules, which are not seen in hepatocellular carcinoma. In domestic animal species, metastatic neoplasia in the liver is more common than primary neoplasia.10

References:

2. Chaiyadet S, Sotillo J, Smout M, Cantacessi C, et al. Carcinogenic liver fluke secretes extracellular vesicles that promote cholangiocytes to adopt a tumorigenic phenotype. J Infect Dis. 2015; 212(10):1636-45.

3. Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:322.

4. Friman S. Cholangiocarcinoma – current treatment options. Scand J Surg. 2011; 100:30-34.

5. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran, Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2010:880-881.

6. Lawrence HJ, Erb HN, Harvey HJ. Nonlymphomatous hepatobiliary masses in

cats: 41 cases (1972 to 1991). Vet Surg. 1994; 23:365–368.

7. Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:385-386.

8. Patnaik AK. A morphological and immunocytochemical study of hepatic

neoplasms in cats. Vet Pathol. 1992; 29:405–415.

9. Tasker S, Griffon DJ, Nuttall TJ, et al. Resolution of paraneoplastic alopecia following surgical removal of a pancreatic carcinoma in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 1999; 40:16-19.

10. World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Standards for the Clinical and Histologic Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2006.

11. Zachary JF, McGavin MD. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis; Mosby Elsevier; 2012:444.