Signalment:

11-year-old female spayed West-Highland white terrier dog (

Canis familiars).This dog had chronic diarrhea for more than 30 days, which was non-responsive to antibiotics. Exploratory surgery revealed numerous small pin-point pale proliferative lesions within the mesentery and on the enteric serosa. The patient was euthanized due to poor prognosis.

Gross Description:

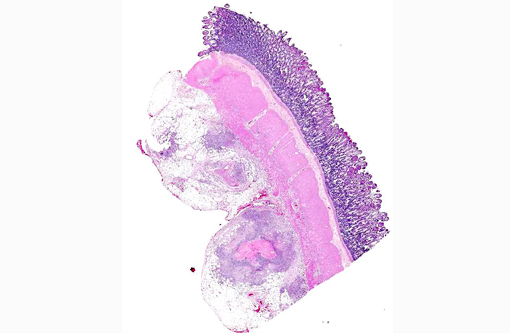

Four images were submitted along with the biopsy by the referring clinician. These images reveal severely thickened and turgid enteric wall. On cut section (upper-right hand), there is marked transmural edema involving predominantly mucosa. The mucosa is diffusely rough, pink and has Turkish-towel-like appearance due to chyle-filled lacteals. Multiple, pale, pin-point, discrete, raised, and sharply demarcated granulomas are present on the enteric serosal surface and in the mesentery (lower left and right-hand images).

Histopathologic Description:

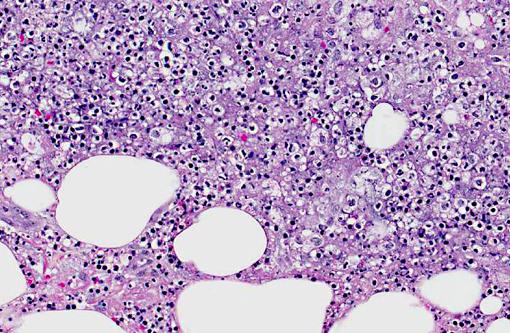

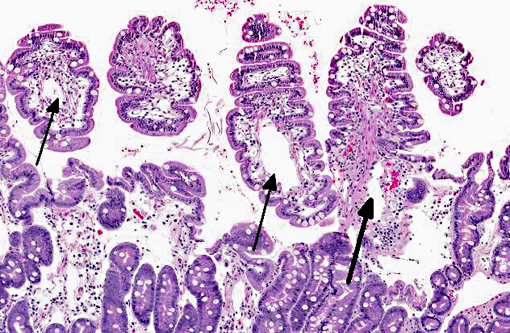

Small intestine - The lacteals are markedly dilated and the lamina propria is expanded by edema. Lymphatics within the submucosa, adventitia, muscularis, and mesentery are dilated and are surrounded by vacuolated lipid-laden macrophages with necrotic cores, rare neutrophils and fibrous connective tissue (lipogranulomas). Fibrosis, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells are scattered within the mesentery.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Small intestine: Severe chronic lymphangiectasia with pyogranulomatous non-mucosal enteritis and lymphangitis.

Lab Results:

Hypoproteinemia.

Condition:

Lymphangectasia

Contributor Comment:

Lymphangiectasia syndrome is a common cause of malabsorption and protein losing enteropathy in dogs. It is characterized by chronic diarrhea, wasting, hypoproteinemia, hypocalcemia, lymphopenia, and hypocholesterolemia. Anorexia, weight loss and steatorrhea are also observed. Yorkshire terriers and Norwegian Lundehunds are predisposed. The lesions of this syndrome grossly resemble an intestinal neoplasm because of the proliferative nature. Patients with this syndrome are often difficult to treat because of the poorly delineated pathogenesis of this condition; typically, these patients have a poor prognosis. The pathogenesis of this syndrome remains unknown. No congenital or acquired cause of lymphatic obstruction is observed in this case. Lipogranulomas are an inconsistent finding considered to be secondary to chronic leakage of lipid-laden chyle. These lesions can secondarily block lymphatics and add to the edema. Malabsorption of lipid from the gut causes diarrhea through the effects of fatty acids on colonic secretion. Hypocalcemia can be due to loss of mineral bound albumin and perhaps due to vitamin D malabsorption or binding of calcium with esterified fatty acids. Lipid malabsorption causes hypocholesterolemia, while lymphopenia is due to loss of lymphocyte-rich lymph into the intestine.(1)

JPC Diagnosis:

Small intestine, submucosa, tunica muscularis, serosa, and mesentery: Lymphangitis, lipogranulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with lymphangiectasia and edema.

Conference Comment:

A distinguishing feature of lymphangiectasia, which is readily apparent in this case, is the even distribution of histological lesions; intestinal lymphatics and lacteals are generally diffusely affected. In contrast, there are few reports focal lipogranulomatous lymphangitis with lymphangiectasia, which manifests as localized masses rather than disseminated intestinal disease. In most of these cases, there is no laboratory evidence of protein losing enteropathy (PLE) and surgical excision appears curative; however, some affected animals do develop signs consistent with PLE, indicating the possibility of disease progression. Both presentations have an unknown pathogenesis and tend to affect older animals, producing vomiting, weight loss, and diarrhea.3

In addition to the idiopathic lymphangiectasia syndrome diagnosed in this case, canine PLE has been associated with alimentary lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease and infectious agents such as

Giardia, Ancylostoma, Histoplasma, Prototheca or

Pythium sp.(2) Gross, histological and clinicopathologic findings, which are comprehensively reviewed above, can help differentiate between these conditions; there are also reports of dogs affected with multiple concurrent causes of PLE.

References:

1. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2007:103-104.

2. Tarpley HL, Bounous DI. Digestive system. In: Latimer KS, ed. Duncan and Prasses Veterinary Laboratory Medicine Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011:244-245.

3. Watson VE, Hobday MM, Durham AC. Focal intestinal lipogranulomatous lymphangitis in 6 dogs (2008-2011). J Vet Intern Med. 2013 Nov 7. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12248. [Epub ahead of print]. Accessed January 11 2014.