CASE IV: 20040779 (JPC 4166757)

Signalment:

1-year-old, castrated male, domestic longhair cat (Felis catus)

History:

This patient presented at a private clinic with a fever (105.3°F), icterus, and thrombocytopenia. The animal progressed to a comatose state within 48 hours. Humane euthanasia and necropsy were performed off-site, and selected tissues were received at Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (OADDL).

Gross Pathology:

No gross findings reported.

Laboratory results:

No laboratory findings reported.

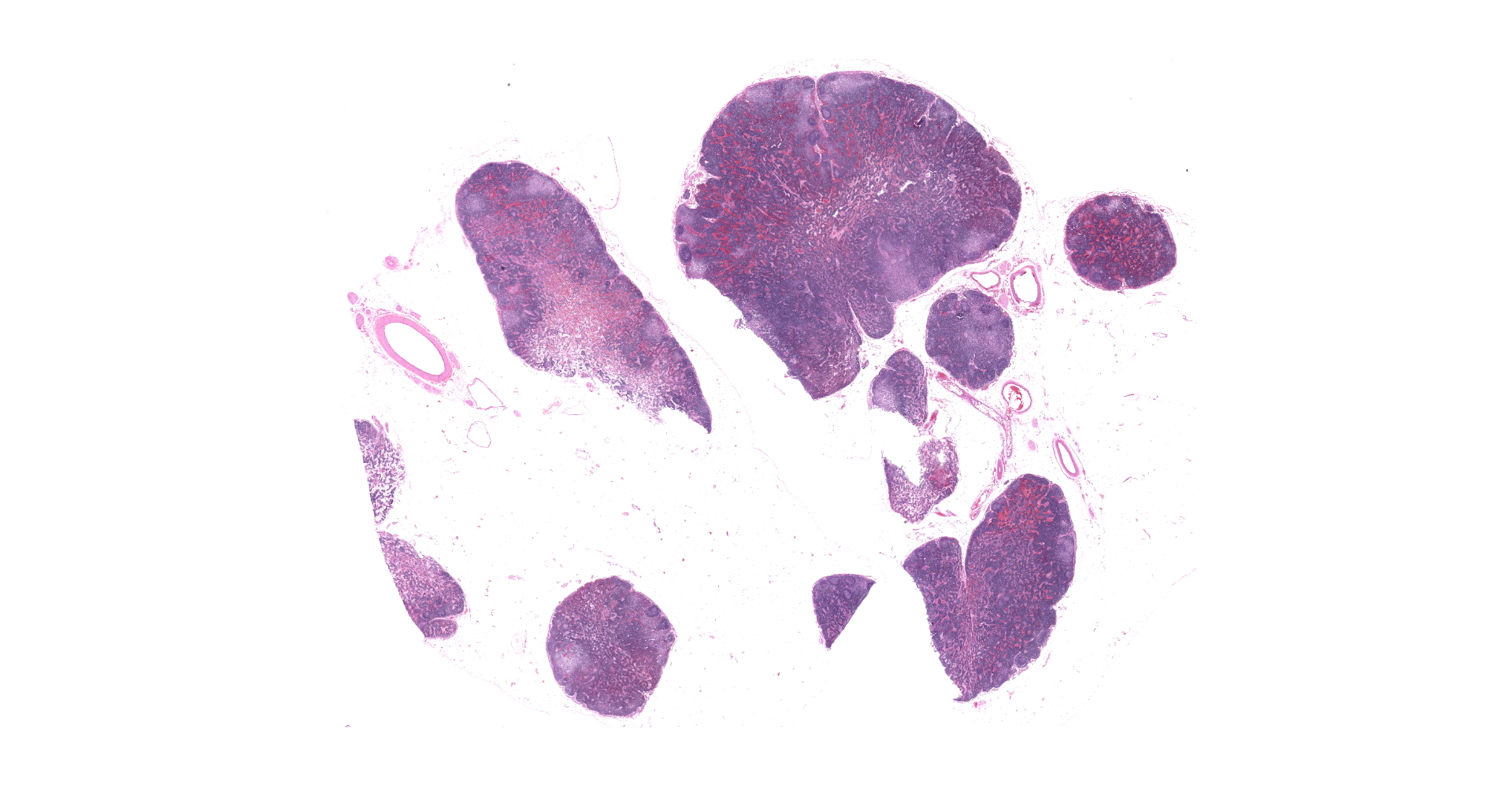

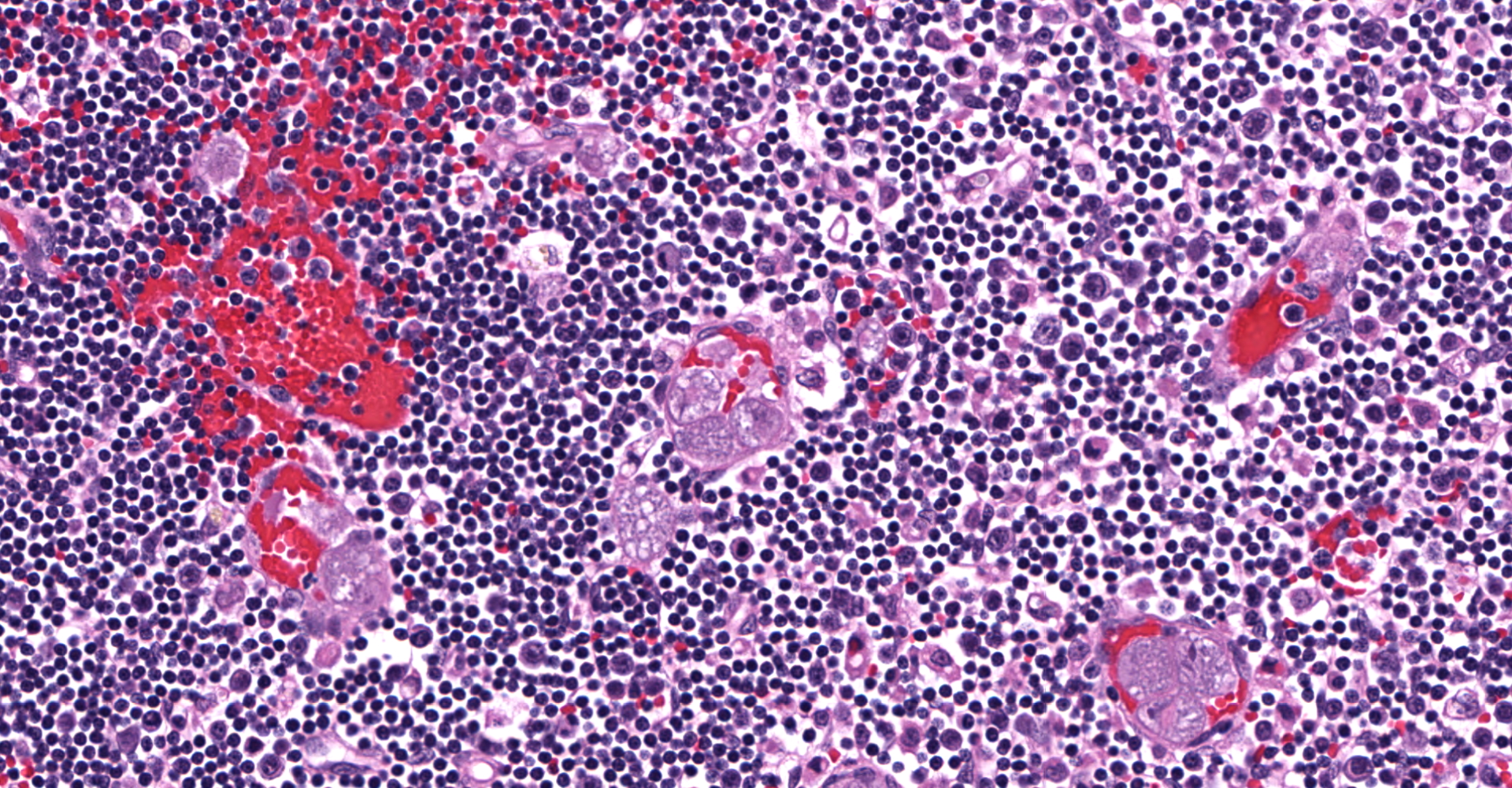

Microscopic Description:

Lymph node: Multifocally expanding blood vessels and extensively scattered within subendothelial spaces, cortical and medullary sinuses, are numerous, discrete, enlarged macrophages, distended up to 55 µm by multiple intracytoplasmic, irregularly round, developing schizonts, containing numerous, 1-3 µm, uninucleate merozoites. Affected blood vessels are congested, and lumina are frequently marginated and occasionally occluded by the schizont-laden macrophages. Small numbers of these vessels are lined by plump, hypertrophic endothelial cells. The connective tissue stroma within the medullary cords is loose and separated by increased amounts of clear space (edema).

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Lymph node: Histiocytosis, intravascular and parenchymal, diffuse, severe with intrahistiocytic schizonts (consistent with Cytauxzoon felis).

Contributor's Comment:

The microscopic features of the lymph node are consistent with a diagnosis of Cytauxzoonosis, which is an emerging, tick-borne, life-threatening disease that affects domestic cats and wildlife felids. Since the first cases reported in Missouri in 1976, this disease has been identified in domestic cats from 17 states from within the United States, mainly in the southern and southeastern regions, and also in a few other countries to include Europe, South America, and Asia.13, 15, 16

The main etiologic agent, Cytauxzoon felis, is an apicomplexan protozoa belonging to order Piroplasmida, family Theileriidiae.7 C. felis infects a variety of wild felids including bobcat (Lynx rufus), Texas cougars (Puma concolor stanleyana) and Florida panthers (Puma concolor coryi), which act as natural reservoirs or incidental hosts in North America.4,12 Infected bobcats rarely have clinical illness but develop a persistent, non-fatal parasitemia as a life-long carrier of this parasite.14 In contrast, domestic cats (Felis catus) infected with C. felis usually show clinical signs at approximately 5-14 days

after exposure to an infected tick.16 Clinical presentation is typically non-specific, with an acute onset of anorexia, lethargy, and fever.7 Other clinical findings exhibited by infected domestic cats, may include increased vocalization, respiratory distress, weakness, icterus, vomiting, abnormal mentation, or moribund.7,13 The duration of illness is extremely rapid and more than 90% of infected domestic cats succumb within days despite medical intervention.3 Domestic cats surviving acute illness, may become asymptomatic carriers with long-term parasitemia for years.8

Transmission of Cytauxzoon felis to a felid host requires a tick vector. Although C. felis has been recovered from both Amblyomma americanum (lone star tick) and Dermancentor variabilis (American dog tick), Amblyomma americanum has been viewed as the primary vector for natural transmission of C. felis in North America, because the geographic distribution of this tick appears to overlap with ranges of reported C. felis infections, in domestic cats.1,5 In the life cycle of C. felis, zygotes develop in tick guts during the sexual phase of reproduction.16 The zygotes mature into mobile ookinetes and migrate to the salivary glands, where sporogony occurs, and then infectious sporozoites are inoculated into the dermis of the felid hosts during tick feeding.13 In the peripheral blood circulation, sporozoites directly enter into mononuclear phagocytic cells and develop into nucleated schizonts. During schizogony, numerous merozoites are formed within mature schizonts that significantly expand the cytoplasm of phagocytes, with an increase in size up to 250 µm in diameter.16 Upon rupture of infected phagocytes, merozoites are released and subsequently taken up by circulating erythrocytes by endocytosis. The intra-erythrocytic merozoites (piroplasms) are 1-2 µm, often "signet-ring" or occasionally "safety pin" shaped, and capable of undergoing asexual reproduction by binary fission and then infecting other erythrocytes.16 Repetition of the asexual cycle results in parasitemia in the host animals. The parasite-laden erythrocytes are ingested by the tick vector, and the merozoites are released from the erythrocytes into the tick guts.13 After gametogenesis and fusion of male and female gametocytes, the life cycle of C. felis is completed.13,16

The schizogenous phase of parasitic replication within the host's mononuclear phagocytic cells is responsible for the primary clinical illness.7 In cats with C. felis infection, the large, schizont-laden macrophages are scattered throughout the body via blood circulation, which may occlude vascular lumina in various organs, particularly lung, liver, spleen, and lymphoid tissues.13 Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and enlarged lymph nodes are often observed at necropsy.2 Additionally, disruption of vascular endothelia resulting in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), is a common complication in naturally infected cats.16 Vascular obstruction, anoxia, severe systemic immune response against the parasites, and cell death, are contributory to multiorgan failure resulting in death of infected cats.6,13 Although the invasion of merozoites into erythrocytes sometimes leads to hemolysis, this parasitic phase (intra-erythrocytic piroplasmosis) is not considered a main contributor to illness.8,13

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathobiology

College of Veterinary Medicine

Oklahoma State University

https://vetmed.okstate.edu/veterinary-pathobiology/index.html

JPC Diagnosis:

Lymph nodes and perinodal fibroadipose tissue: Apicomplexan schizonts, intrahistiocytic, intra- and extravascular, numerous, with diffuse mild reactive hyperplasia and draining hemorrhage, etiology consistent with Cytauxzoon felis.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a detailed and thorough overview of Cytauxzoon felis, an emerging tick-borne disease of domestic and wild felids first reported as a parasite of domestic cats in Missouri by Wagner in 1976.10,13

Cytauxzoon spp. are closely related to Thelieria spp. and are classically differentiated based on leukocyte predilection in their vertebrate hosts. Thelieria spp. undergo schizogony in lymphocytes with multiple fission in erythrocytes whereas Cytauxzoon spp. undergo schizogony within histiocytes and binary fission within erythrocytes. However, differentiation between these genera based on host leukocyte predilection may be inadequate and in need of reconsideration.10

C. felis has historically been considered to be highly fatal in domestic cats. However, recent studies have found there is a significant subpopulation of subclinically infected domestic cats in the United States. Using PCR amplification with C. felis specific primers, 902 blood samples from healthy asymptomatic cats from Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma were evaluated. 15.5%, 12.9%, and 3.4%, respectively, were infected with C. felis in one study.11 A similar study of 1104 healthy cats in Kansas found 25.8% were subclinically infected.17 Similar to the bobcat, transmission of C. felis from subclinically infected domestic cats to naïve cats via A. americanum has been observed in multiple studies. Therefore, it is likely these chronically infected cats serve as an important reservoir of infection to other domestic cats.10

An additional interesting case of likely C. felis transmission was reported in Switzerland, involving a subclinical blood donor. Following transfusion, the recipient demonstrated intra-erythrocytic inclusions. C. felis was confirmed in both donor and recipient using PCR and sequencing of 1637 bp of the 18S rRNA gene with 100% nucleotide sequence identity. Therefore, it may be prudent to screen healthy blood donor cats for this agent by PCR, particularly given the aforementioned rates of subclinically infected domestic cats in endemic areas.9

References:

1. Allen KE, Thomas JE, Wohltjen ML, Reichard M V. Transmission of Cytauxzoon felis to domestic cats by Amblyomma americanum nymphs. 2019;12:1?6.

2. Aschenbroich SA, Rech RR, Sousa RS, Carmichael KP, Sakamoto K. Pathology in practice. Cytauxzoon felis infection. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2012 Jan;240:159?161.

3. Birkenheuer AJ, Le JA, Valenzisi AM, Tucker MD, Levy MG, Breitschwerdt EB. Cytauxzoon felis infection in cats in the mid-Atlantic states: 34 Cases (1998-2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;228:568?571.

4. Blouin EF, Kocan AA, Kocan KM, Hair J. Evidence of a limited schizogonous cycle for Cytauxzoon felis in bobcats following exposure to infected ticks. J Wildl Dis. 1987;23:499?501.

5. Bondy PJ, Cohn LA, Tyler JW, Marsh AE. Polymerase chain reaction detection of Cytauxzoon felis from field-collected ticks and sequence analysis of the small subunit and internal transcribed spacer 1 region of the ribosomal RNA gene. J Parasitol. 2005;91:458?461.

6. Frontera-Acevedo K, Balsone NM, Dugan MA, et al. Systemic immune responses in Cytauxzoon felis-infected domestic cats. Am J Vet Res. 2013;74:901?909.

7. Lloret A, Addie DD, Boucraut-Baralon C, et al. Cytauxzoonosis in cats: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17:637?641.

8. Meinkoth J, Kocan AA, Whitworth L, Murphy G, Fox JC, Woods JP. Cats surviving natural infection with Cytauxzoon felis: 18 cases (1997-1998). J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14:521?525.

9. Nentwig A, Meli ML, Schrack J, et al. First report of Cytauxzoon sp. infection in domestic cats in Switzerland: natural and transfusion-transmitted infections. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):292.

10. Reichard MV, Sanders TL, Weerarathne P, et al. Cytauxzoonosis in North America. Pathogens. 2021;10(9):1170. Published 2021 Sep 10.

11. Rizzi TE, Reichard MV, Cohn LA, Birkenheuer AJ, Taylor JD, Meinkoth JH. Prevalence of Cytauxzoon felis infection in healthy cats from enzootic areas in Arkansas, Missouri, and Oklahoma. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:13.

12. Rotstein DS, Taylor SK, Harvey JW, Bean J. Hematologic effects of cytauxzoonosis in Florida panthers and Texas cougars in Florida. J Wildl Dis. 1999;35:613?617.

13. Sherrill MK, Cohn LA. Cytauxzoonosis: Diagnosis and treatment of an emerging disease. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17:940?948.

14. Shock BC, Murphy SM, Patton LL, et al. Distribution and prevalence of Cytauxzoon felis in bobcats (Lynx rufus), the natural reservoir, and other wild felids in thirteen states. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:325?330.

15. Wagner JE. A fatal cytauxzoonosis-like disease in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1976 Apr;168:585?588.

16. Wang JL, Li TT, Liu GH, Zhu XQ, Yao C. Two tales of cytauxzoon felis infections in domestic cats. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:861?885.

17. Wikander YM, Anantatat T, Kang Q, Reif KE. Prevalence of Cytauxzoon felis Infection-Carriers in Eastern Kansas Domestic Cats. Pathogens. 2020;9(10):854.