Signalment:

Histopathologic Description:

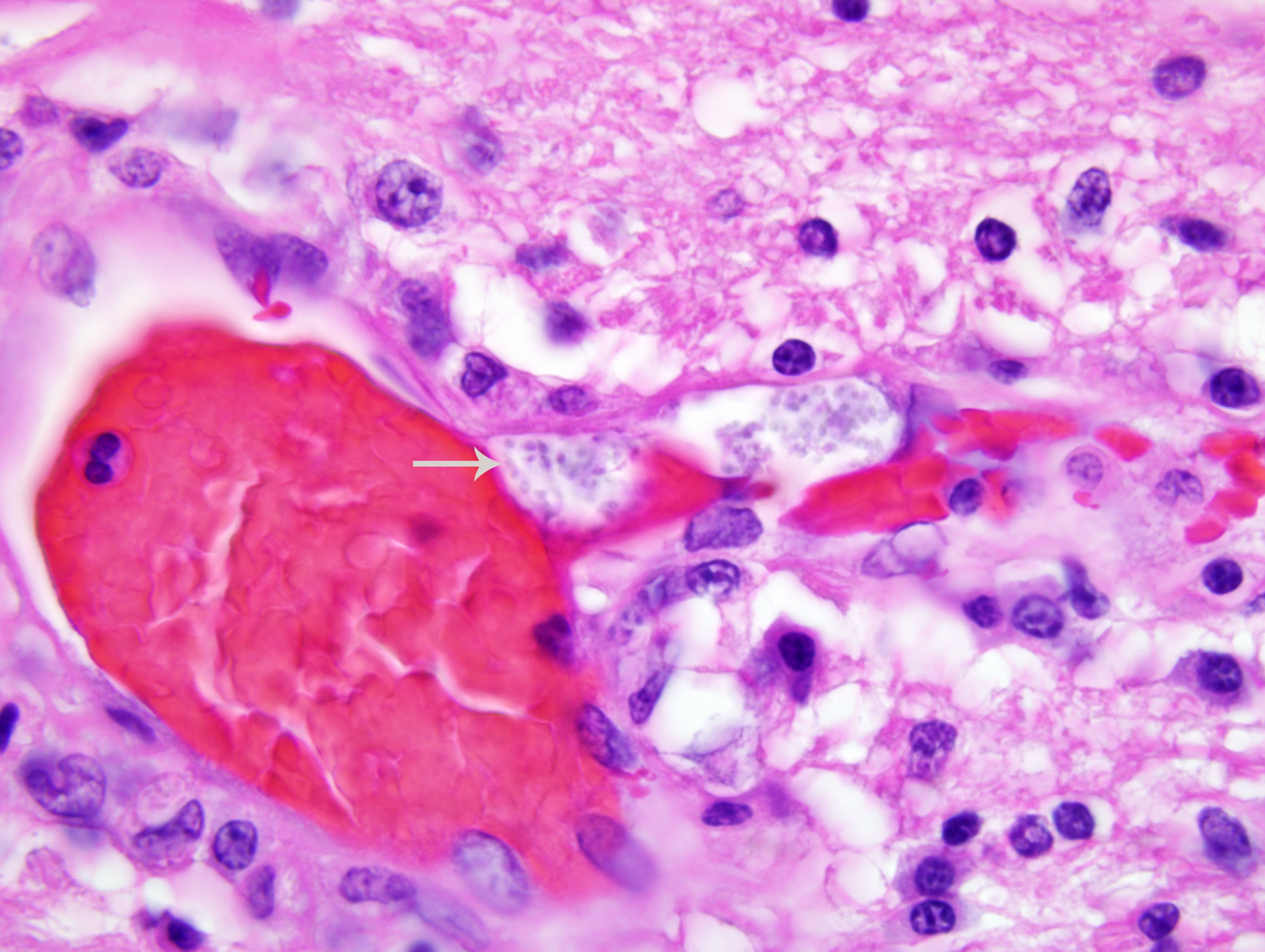

The kidney has diffuse interstitial inflammation composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells within the cortex and similar, but milder inflammation, within the medulla. Extensive cortical tubular necrosis is present and occasional necrosis of medullary tubules is seen. Occasional clusters of organisms are present within cortical tubular epithelial cells and vascular lumina.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Encephalitis and meningitis, lymphoplasmacytic, diffuse, severe with intralesional protozoa consistent with Encephalitozoon.

2. Interstitial nephritis, lymphoplasmacytic, diffuse, severe with intralesional protozoa consistent with Encephalitozoon.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Encephalitozoonosis is a systemic disease of neonatal dogs that tends to localize in the kidney and brain. Clinical signs are neurologic in origin. Gross lesions are often absent but radial streaks may be seen in the kidneys. Histopathology reveals a lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis and meningoencephalitis. Spores may be visible in the lesions with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, but are few and difficult to see. The spores are rodshaped, 1-3 μm in diameter, and form aggregates within a parasitophorous vacuole. They are located predominantly within endothelial cells but can be found in epithelial cells and macrophages. Spores are gram-positive and are easily visualized with a Grams stain.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Brain, cerebrum and hippocampus: Meningoencephalitis, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, multifocal, moderate, with neuronal necrosis, gliosis, and intraendothelial anisotropic microsporidia.

2. Kidney: Nephritis, interstitial, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate to marked, with pyelitis, tubular degeneration and necrosis, and few anisotropic microsporidia.

Conference Comment:

Discussion during the conference was primarily devoted to the comparative pathology of mammalian microsporidiosis in general, and encephalitozoonosis in particular. Microsporidia have an obligate intracellular life stage, and exist as environmentally resistant spores outside the host. The polar filament, the defining morphologic feature of the microsporidia, is a unique organelle that remains coiled within the spore until stimulated by some poorly-defined environmental signal to extrude. Upon extrusion, the polar filament penetrates a host cell and injects infectious sporoplasm, which then divides to form meronts, which further differentiate into sporoblasts, sporonts, and spores; these may be contained within a parasitophorous vacuole, as in the case of Encephalitozoon spp., or may remain free in the cytoplasm, as in the case of Enterocytozoon bieneusi. Other typical microsporidian features include a proteinaceous exospore; a chitinous endospore; an anchoring disc at the anterior pole; an electron-lucent posterior vacuole; and a distinct lack of mitochondria, peroxisomes, and stacked Golgi membranes at all developmental stages. In addition to polar filament extrusion, phagocytosis of spores by host cells may also produce intracellular infection.(2)

Best characterized in rabbits, the species in which it was first identified, spontaneous encephalitozoonosis has also been described in numerous other species, including guinea pigs, mice, rats, hamsters, muskrats, ground shrews, goats, sheep, pigs, horses, dogs, foxes, cats, exotic carnivores, humans, and nonhuman primates. Generally, infection in immunocompetent rabbits, guinea pigs, mice, and squirrel monkeys is subclinical, whereas infection in domestic dogs, farm-raised blue foxes, and immunocompromised mice and humans results in clinical disease. As noted by the contributor and illustrated by this case, infection in carnivores often results in fulminating disease. In particular, domestic dogs in South Africa and the United States, and farm-raised blue fox kits in Scandinavian countries have been affected in outbreaks. Gross lesions include pale streaks extending from the renal cortex to the renal pelvis; edematous meninges; and thickened, tortuous, medium-sized to small arteries in the heart, intestines, and central nervous system, reminiscent of polyarteritis nodosa. Microscopic lesions include lymphoplasmacytic meningoencephalitis, lymphoplasmacytic nephritis, microgranulomatous hepatitis, and interstitial pneumonia.(2)

In rabbits, E. cuniculi is shed in the urine and the ingestion of infective urine is the primary route of infection. The brain and kidney are the organs primarily affected, and usually do not exhibit any gross abnormalities, although multifocal irregularly-shaped depressions in the renal cortex are sometimes present. Microscopic lesions in the brain include multifocal nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis, astrogliosis, and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation; lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis is the typical renal lesion. The microsporidian organisms are primarily identified within epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and/or macrophages of affected tissues, but also are commonly found in the lens, lung, liver, and/or heart.(2)

In guinea pigs, as in rabbits, encephalitozoonosis is usually subclinical, but may result in multifocal necrotizing and granulomatous encephalitis and interstitial nephritis. In mice, E. cuniculi results in mononuclear inflammatory foci in the liver, lungs, and brain; the differential diagnosis includes Clostridium piliforme, Corynebacterium kutscheri, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella species, mouse hepatitis virus (coronavirus), and ectromelia virus (mousepox). Infection in squirrel monkeys is also typically subclinical, but has been implicated in cases of granulomatous encephalitis, nonsuppurative meningitis, and vasculitis in immunosuppressed and neonatal animals; in utero infection is suspected in the latter. Interestingly, microsporidiosis in psittacines is reported with increasing frequency, and many cases are caused by Encephalitozoon hellem. Microsporidiosis is an emerging human disease, largely attributed to growing populations of immunocompromised hosts; E. bieneusi is the most frequently diagnosed microsporidian pathogen in humans, but disease is also attributed to E. cuniculi, E. hellem, and Encephalitozoon intestinalis.(2)

References:

2. Wasson K, Peper RL: Mammalian microsporidiosis. Vet Pathol 37:113-118, 2000