WSC 22-23:

Conference 4 Case 1

CASE I:

Signalment:

14-year-old, intact female Alpaca (Vicugna pacos)

History:

Per attending veterinarian: ?Presented with hypernatremia, mild azotemia, decreased albumin, treated last week with IV fluids, electrolytes. Suspect bilateral polycystic kidney disease.?

Gross Pathology:

The peritoneal, pleural and pericardial cavities contained approximately 2L, 1.5L and 10mL of clear, yellow watery fluid with scant fibrin strands. The pleural surfaces of the lung lobes contain scant, scattered fibrin strands. The lungs are diffusely wet, heavy and meaty and did not collapse when the chest cavity was opened. The lungs contain enumerable, individual to coalescing nodules ranging from 0.2cm-2cm. (Refer to attached digital image, 15041635). The nodules are firm and white; some of the larger nodules contain central caseous material.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

Microscopic Description:

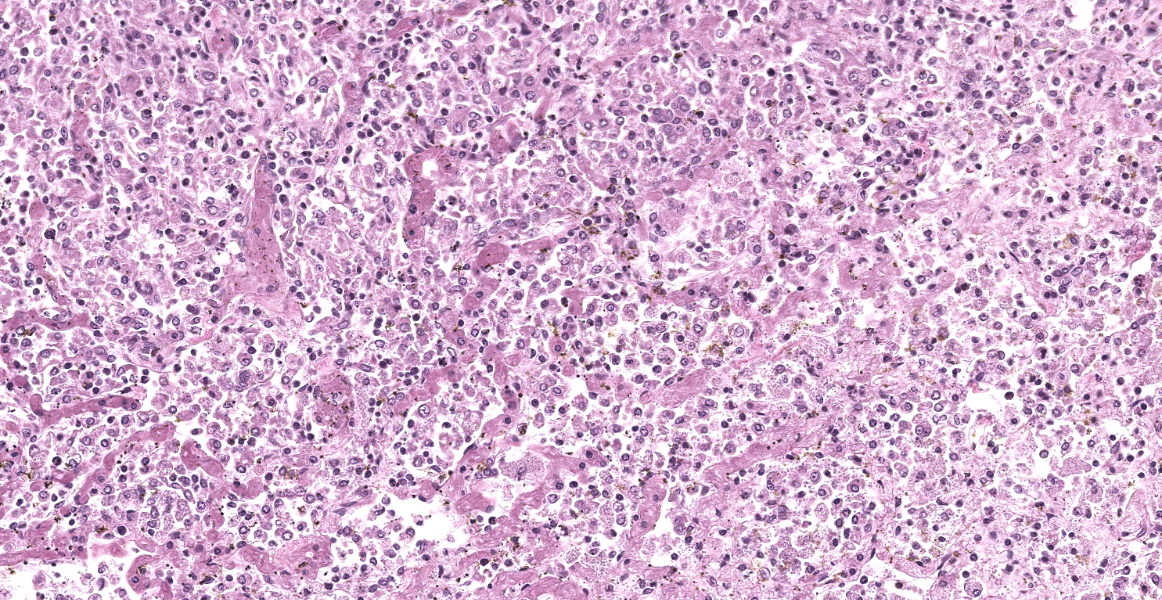

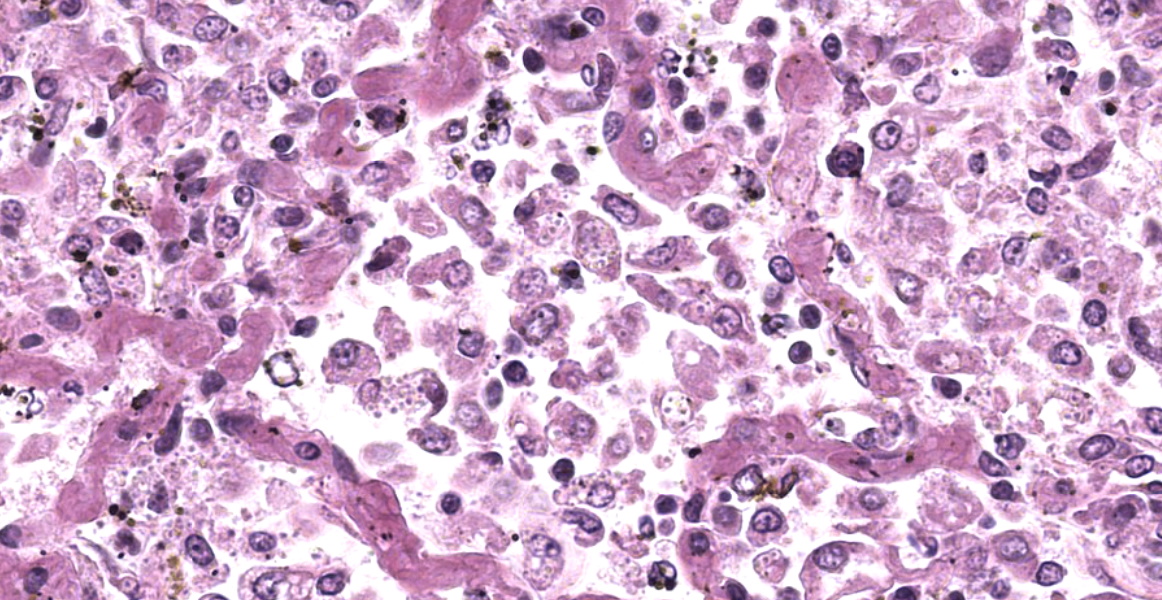

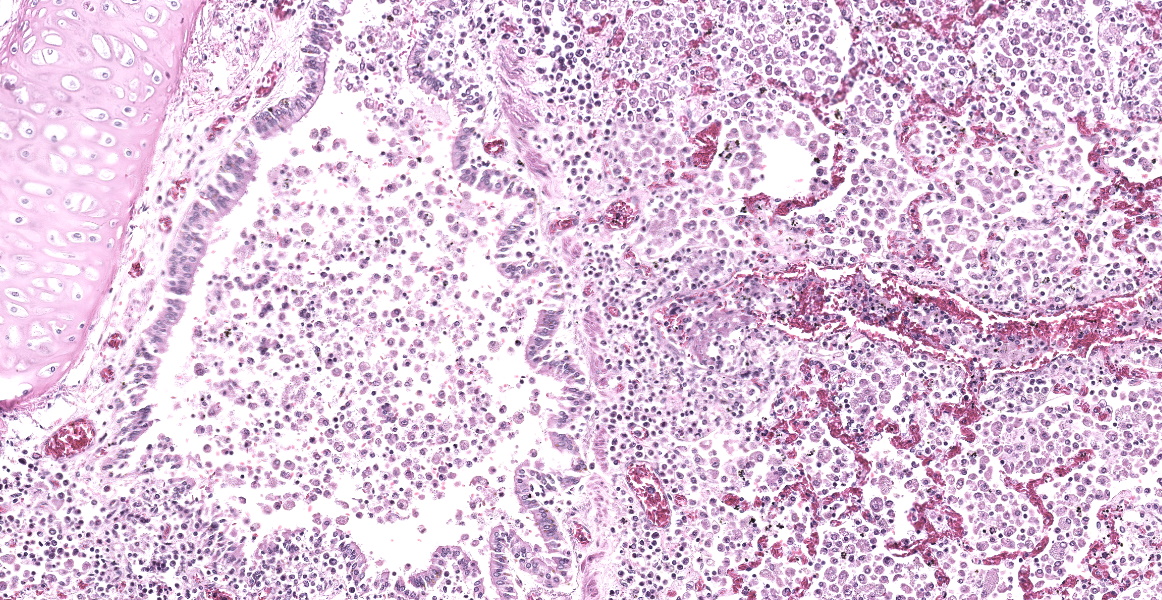

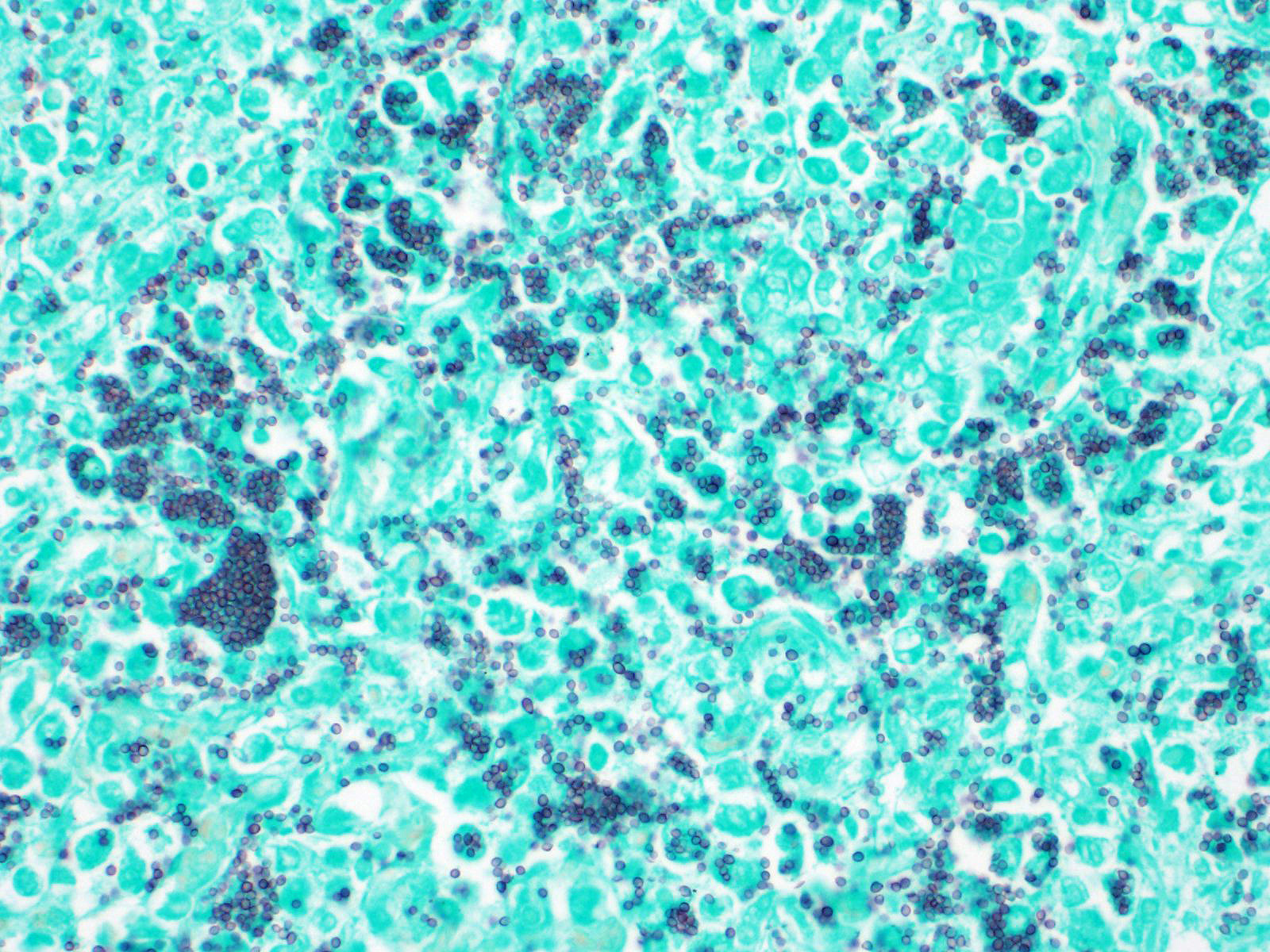

The open alveolar architecture of the lung is nearly diffusely effaced secondary to alveolar filling by numerous macrophages, epithelioid macrophages and fewer multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Randomly scattered conspicuous aggregates of neutrophils (intact and degenerate) randomly interrupt the otherwise monotonous infiltrate by macrophages. When visible, alveolar septa are thickened approximately 2X expected by congestion. Many of the macrophages contain numerous yeast organisms; the yeast organisms were characterized by a 1.0µm, round to crescent-shaped yeast body surrounded by a variably-sized (1.0-2.0µm) halo.

In addition to the lung (provided), sections of the liver and spleen also contained randomly distributed aggregates of macrophages (some with epithelioid morphology and multinucleated giant cells) containing yeast organisms similar to that described in the lung.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Syndrome: Disseminated histoplasmosis

- Severe, diffuse, granulomatous pneumonia with myriad intralesional yeast organisms consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum.

- Severe, multifocal, granulomatous splenitis with myriad intralesional yeast organisms consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum.

- Severe, multifocal, granulomatous hepatitis myriad intralesional yeast organisms consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum.

Contributor?s Comment:

This patient originally presented with a history and clinical diagnosis of renal disease. The severe pneumonia, as well as other lesions secondary to histoplasmosis, were a surprise finding at necropsy. After the fact query of the attending veterinarian did not reveal any mention of clinical signs of respiratory disease.

Our institution has a respectable caseload of llamas/alpacas; however, disseminated histoplasmosis has not before been seen, even as an etiology for pneumonias. A literature search revealed a single case report of pulmonary histoplasmosis in a llama.11 The patient in that report had been recently imported from Bolivia 7-mos prior; however, the patient in this report had spent its entire life in the United States.

Histoplasma capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus commonly found in soil that has been contaminated with bird feces or bat guano.1 Within the United States, histoplasmosis is most common in the Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio river valleys; however, infections are certainly not uncommon elsewhere in the Midwest.5 The organism exists in the soil as a mold producing infective microconidia.1 When inhaled, the microconidia convert to yeast forms that replicate within phagolysosomes of the pulmonary mononuclear-phagocytic system.1,6 From this initial pulmonary infection, the organism disseminates into other organs by hematogenous (spleen, liver) or lymphatic (lymph node) routes.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathobiology &

The Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory

Center for Veterinary Health Sciences

Oklahoma State University

JPCDiagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, granulomatous, diffuse, severe with numerous intrahistiocytic yeasts.

JPC Comment:

During the conference, participants discussed the similar histologic morphology of this entity to Sporothrix schenkii, and that definitive diagnosis may require speciation through culture, PCR, or IHC.

Histoplasma capsulatum subs. capsulatum infects a wide variety of mammals (including humans) and birds, and most infections are likely subclinical or mild due to effective adaptive immunity involving cytokine-mediated macrophage killing and T-cell response.9 Overt pulmonary or disseminated infections may occur if the animal is exposed to a large dose of infectious microconidia or is immunosuppressed.1, 9 Dogs and cats are most commonly affected by clinical disease, but a plethora of reports demonstrate that disseminated histoplasmosis can occur in many species, including goats and raccoons, or as seen in this case, an alpaca.8, 2 Even if an effective immune response is generated, yeast may enter a state of dormancy and re-emerge when the animal becomes immunocompromised.1,9 In disseminated infections, Histoplasma travels in phagocytic cells to other organs with high concentrations of phagocytes, such as lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, spleen, and liver. Spread to the adrenal glands, skin, eye, and bone is also possible.9

In most cases, the host develops an appropriate adaptive immune response which controls and eliminates the Histoplasma infection. In immunocompetent hosts, the Th1 response is critical in controlling infection.6 Innate cells initially produce IL-12, which stimulates the production of IFN-gamma mostly by CD4+ T cells.6 IFN-gamma has a wide range of effects including activation of macrophages, stimulation of intracellular nitric oxide production by macrophages, and regulation of iron and zinc availability.6 T cells also produce TNF-alpha, which further stimulates nitric oxide production, chemokine production, and increased INF-gamma production.6 TNF-alpha also restricts expansion and trafficking of regulatory T cells and signals for apoptosis.6 These proinflammatory cytokines stimulate expression of CCR5, the receptor for chemokines CCL3, CCL4, and CCL5, all of which become upregulated during Histoplasma infection.6 CCR5 activation leads to influx of additional inflammatory cells.6 These cytokines also activate macrophages to produce microbe-killing agents such as reactive oxygen species (ROS).12

The NADPH-oxidase system produces many of these reactive oxygen species, including superoxide, hydroxyl, and peroxide, to neutralize and destroy microbes, and Histoplasma has evolved a few tricks to resist ROS destruction. H. capsulatum produces two catalases, CatB (M-antigen) and CatP, which create a layered defense by neutralizing extracellular and intracellular ROS, respectively.12 H. capsulatum also produces superoxide dismutases, such as extracellular Sod3 and intracellular Sod1, which add to these defenses.12 Other mechanisms that Histoplasma has evolved to evade non-oxidative host defenses include producing anti-inflammatory IL-4, melanin, and substances which increase intracellular pH.1

Other pathogenic H. capsulatum species include H. capsulatum var. farciminosum (HCF) and H. capsulatum var. duboisii (HCD). HCF, or equine histoplasmosis, causes epizootic lymphangitis (pseudoglanders) in horses and mules.7 The yeast enters open wounds in the skin and causes swollen lymphatics and chronic, progressive, ulcerative nodules that drain and scar.7 Less commonly, HCF can cause rhinitis, sinusitis, pneumonia, or keratoconjunctivitis.7H. capsulatum var. duboisii causes African histoplasmosis, which is characterized by granulomatous inflammation within the skin and bone of baboons and humans, though disseminated disease can also occur.3 A recent report described granulomatous gingivitis due to HCD infection in three baboons.4

References:

- Brömel C, Green CE. Histoplasmosis. In: Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th St. Louis, MO, USA: Saunders; 2012: 614-621.

- Clotheir KA, Villaneuva M, Torain A, Reinl S, Barr B. Disseminated histoplasmosis in two juvenile raccoons (Procyon lotor) from a nonendemic region of the United States. Jour Vet Diag Invest. 2014; 26(2):297-301.

- Hensel M, Hoffman AR, Gonzales M, Owston MA, Dick EJ. Phylogenic analysis of Histoplasma capsulatum var duboisii in baboons from archived formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissues. Medical Mycology. 2019; 57:256-259.

- Johannigman TA, Gonzalez O, Dutton JW, Kumar S, Dick EJ. Gingival histoplasmosis: An atypical presentation of African Histoplasmosis in three baboons (Papio spp). J Med Primatol. 2020; 49(1): 47-51.

- Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007; 20:115-132.

- Kroetz DN, Deepe GS. The role of cytokines and chemokines in Histoplasma capsulatumCytokine. 2012; 58:112-117.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016: 97-98.

- Schlemmer SN, Fratzke AP, Gibbons P, et al. Histoplasmosis and multicentric lymphoma in a Nubian goat. Journ Vet Diag Invest. 2019; 31(5): 770-773.

- Valli VEO, Kiupel M, Bienzle D. Hematopoietic System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016: 186-187.

- Woods JP. Knocking on the right door and making a comfortable home: Histoplasma capsulatum intracellular pathogenesis. Curr Opinion in Microbiol. 2003; 6:327-331.

- Woolums AR, DeNicola DB, Rhyan JC, Murphy DA, Kazacos KR, Jenkins SJ, Kaufman L, Thronburg M. Pulmonary histoplasmosis in a llama. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1995; 7:567-569.

- Youseff BH, Holbrook ED, Smolnycki KA, Rappleye CA. Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase Protects Histoplasma Yeast Cells from Host-Derived Oxidative Stress. PLoS Pathog. 2012; 8(5): e1002713.