Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 16

29 January 2020

Dr.

Ingeborg Langohr, DVM, PhD, DACVP

Professor

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine

Baton Rouge, LA

CASE III: P590-19 (JPC 4136500).

Signalment: 5½ week-old, neutered male, crossbred Landrace, Sus scrofa domesticus, domestic pig.

History: Two out of 950 weanling piglets showed clinical signs described as paresis progressing to paralysis affecting mostly the forelimbs; they were otherwise alert. The piglets were euthanized and rapidly brought to our diagnostic laboratory for a complete autopsy.

Gross Pathology: No gross lesions were seen.

Laboratory results: PCR for PRRSV at our institution was negative on samples of brainstem and spinal cord. Similar samples were sent to the Iowa State University's Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for PCR and were positive for porcine sapelovirus and negative for porcine teschovirus.

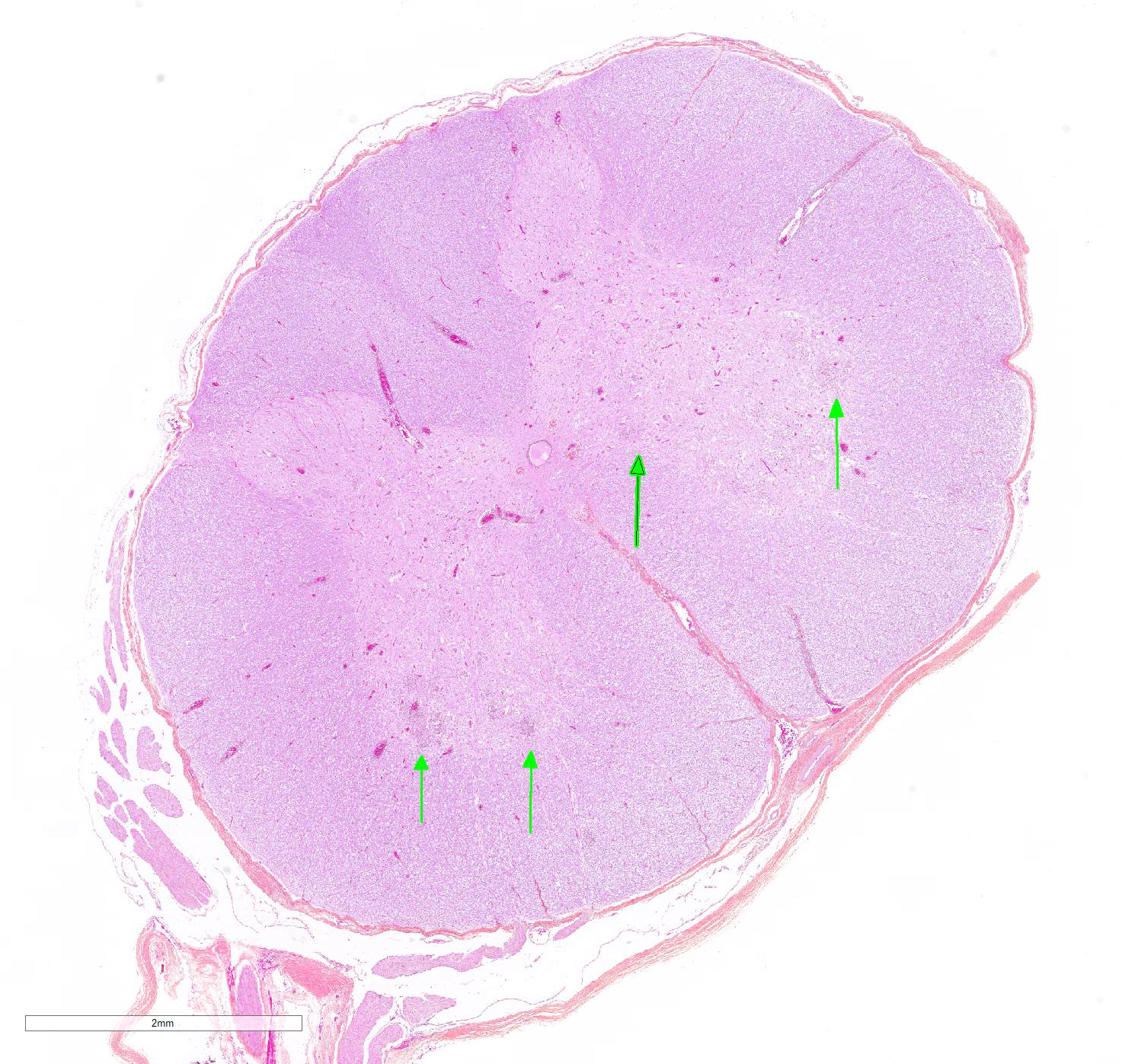

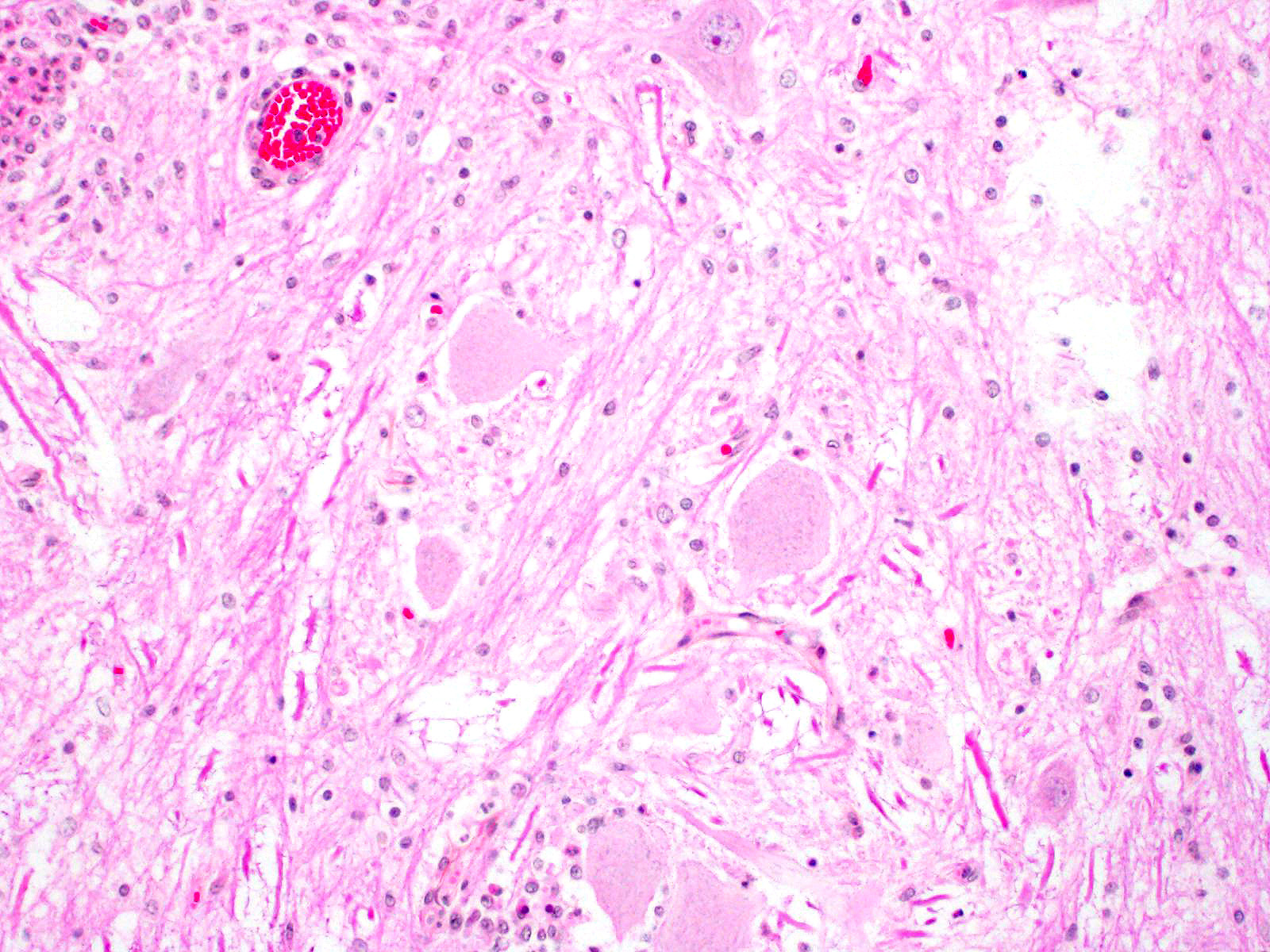

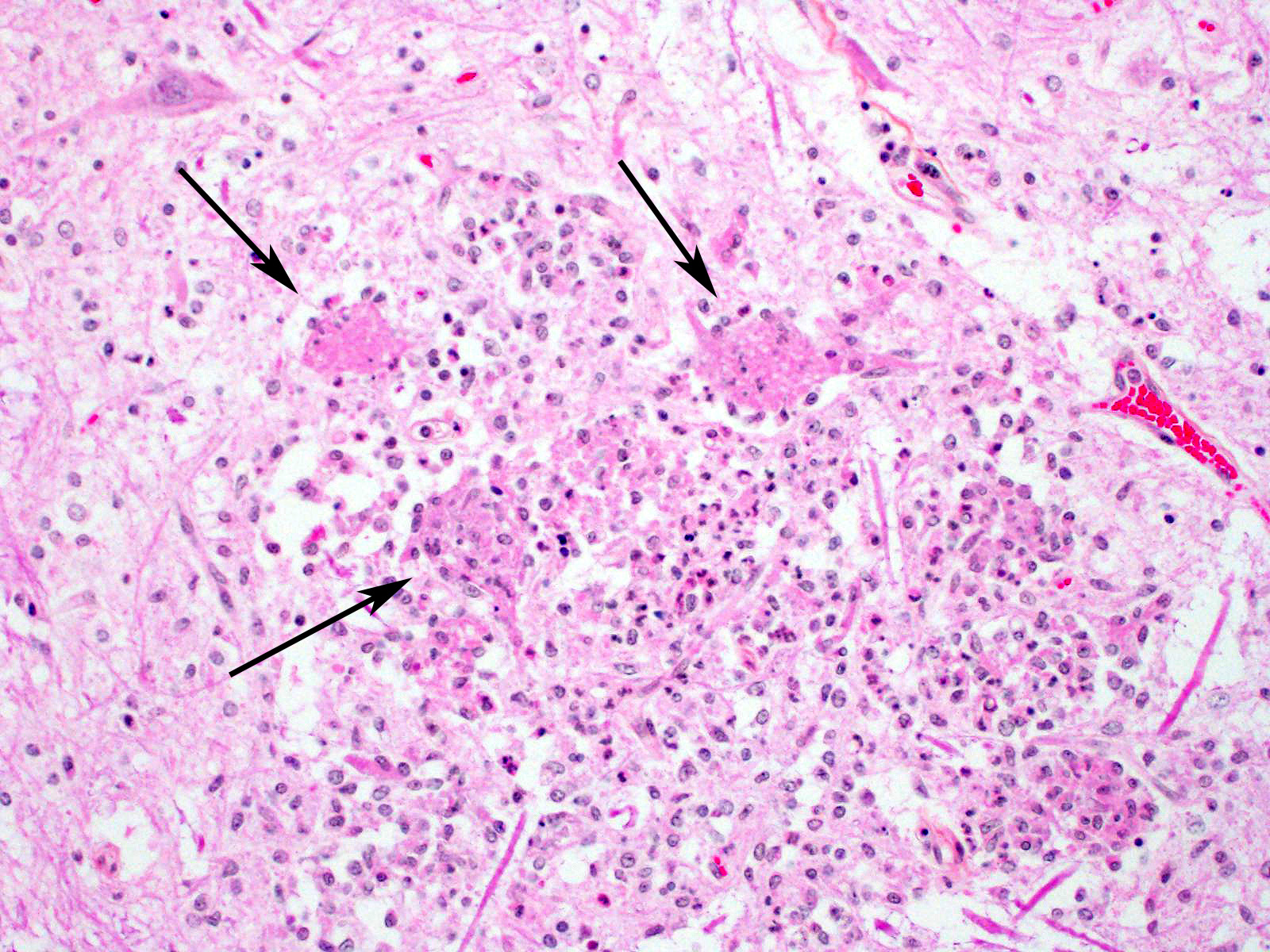

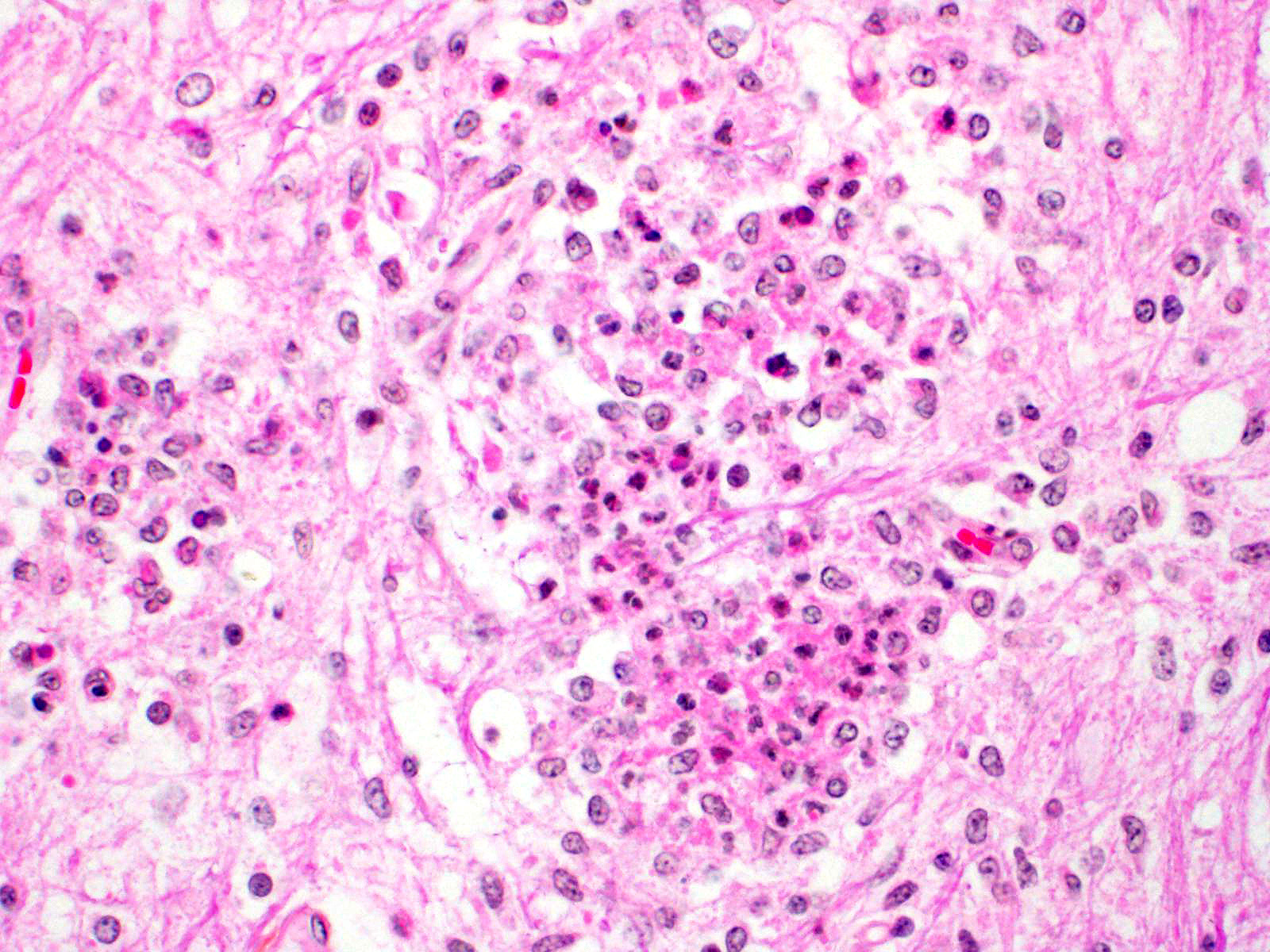

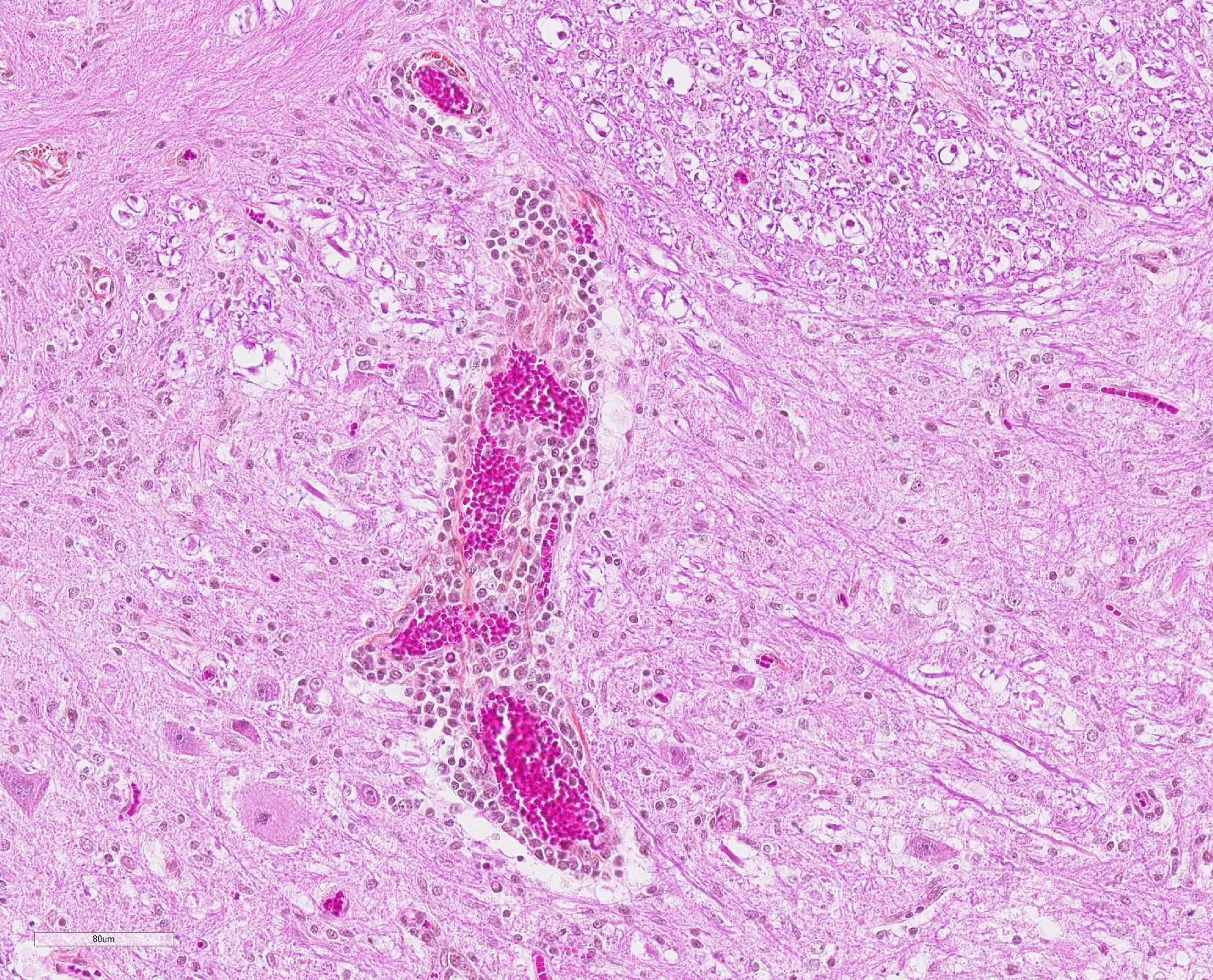

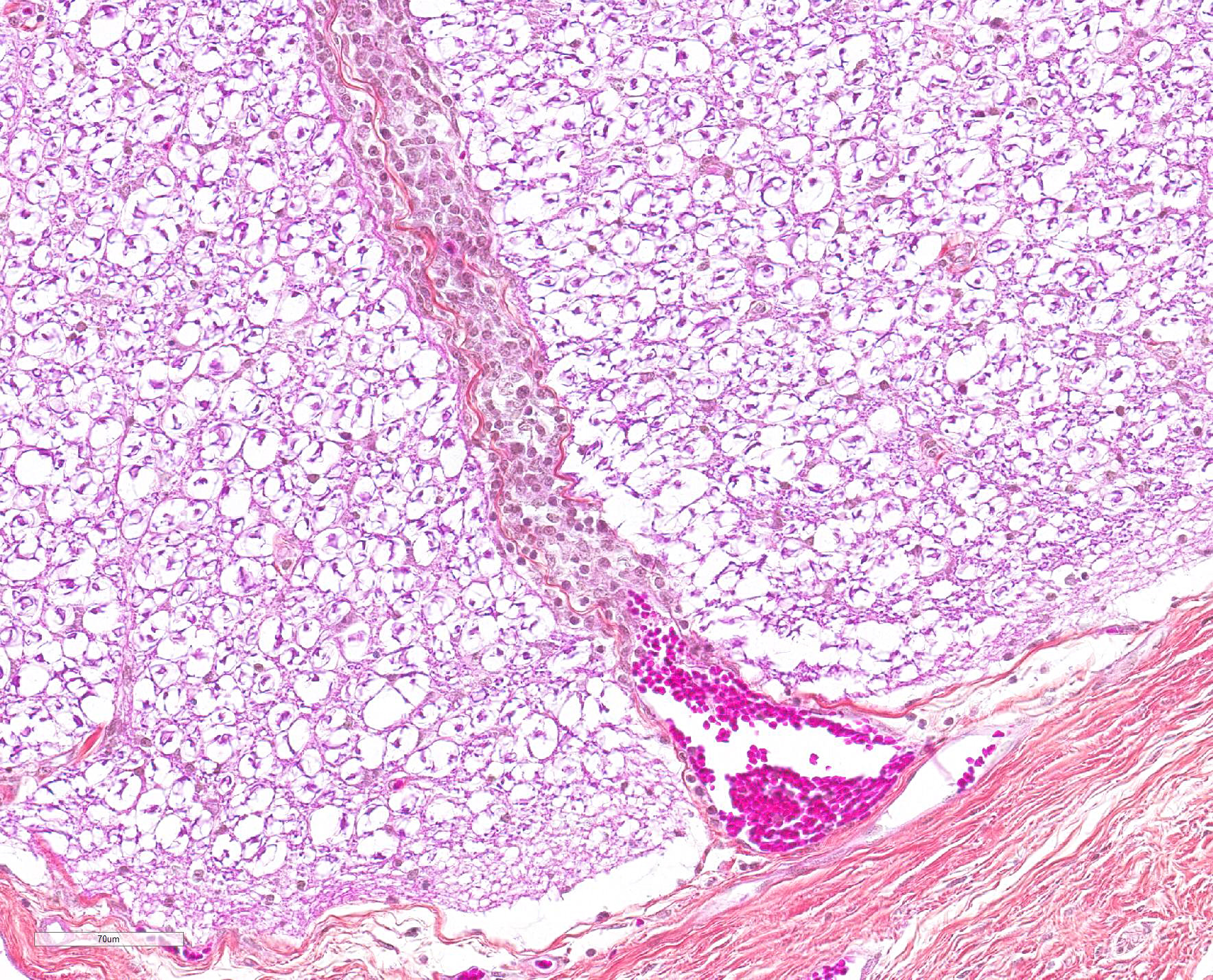

Microscopic Description: In this section of spinal cord, lesions involve the grey matter, predominantly the ventral horns. There is marked neuronal degeneration, necrosis and loss. Necrotic neurons are surrounded, infiltrated and eventually replaced by activated microgliocytes (neuronophagia and microglial nodules) with a few admixed neutrophils (Fig. 1). Necrotic neurons are shrunken with a hypereosinophilic, sometimes vacuolated cytoplasm, and the nucleus is often not visible. There is mild to moderate, multifocal perivascular cuffing by lymphocytes with fewer plasma cells also involving, but to a lesser degree, the leptomeninges.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Mild to moderate lymphoplasmacytic poliomyelitis with marked neuronal degeneration/necrosis (nonsuppurative necrotizing poliomyelitis).

Contributor Comment: These lesions were diffuse in the spinal cord, but more severe in the cervical and cranial thoracic segments, consistent with the reported clinical signs. Lesions similar in nature and intensity were present in the brainstem, mainly in the medulla and pons, but also involved the white matter, albeit more mildly. Significant lesions were not present in the cerebellum or cerebrum (minimal lymphocytic meningitis) nor in other organs. The nature of the lesions, i.e. nonsuppurative inflammation involving preferentially the grey matter with neuronal necrosis and microglial nodules, was highly suggestive of a neuronotropic viral infection. Selenium toxicosis causes bilateral symmetrical poliomyelomalacia in the ventral horns, but it was not considered here as it is malacic (necrosis of all CNS components, not only neurons) in nature, and does not cause neuronophagia/microglial nodules or inflammation (although primarily malacic conditions will eventually incite inflammation with microglia, macrophages, and gitter cells). The viral etiologies considered in our geographical area (northeastern North America) were porcine teschovirus A (PTV), porcine sapelovirus A (PSV), porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (PHEV) and, to a lesser degree, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV-2). These viruses are all specific to the porcine species (in natural disease). The final diagnosis, based on histopathology and PCR results, was encephalomyelitis due to PSV infection.

Porcine teschovirus A (PTV), formerly known as porcine enteroviruses (PEV) 1-7 and 11-13, is a member of the Picornaviridae family, which also includes porcine sapelovirus A (PSV) and porcine enteroviruses (PEV).1 PTV causes a polioencephalomyelitis in pigs known as Teschen and/or Talfan disease; it has also been associated with reproductive failure. Teschen disease, the first one reported, is clinically severe (high morbidity and mortality) and limited mostly to Europe while Talfan disease, reported 20 years later, is a milder form (infection is usually asymptomatic) and is cosmopolitan.1,2,7 Porcine sapelovirus A (PSV), formerly known as porcine enterovirus (PEV) 8, also causes a polioencephalomyelitis that is essentially similar to PTV, and has only been relatively recently reported in North America in 11 week-old pigs (20% morbidity; 30% mortality); it has also been associated with enteritis, pneumonia and reproductive failure. In contrast to PTV, the pathogenesis of PSV polioencephalomyelitis is still largely unknown and, to our knowledge, the disease has not been experimentally reproduced; PSV, but not PTV, is known to be cytopathic in porcine kidney cells.1 Both PSV and PTV, like PEV, can be found in feces of normal pigs; thus, CNS sampling must be done as aseptically as possible.1 Microscopic lesions in PTV and PSV are characterized by nonsuppurative polioencephalomyelitis with neuronal degeneration/necrosis and gliosis. Lesions are usually present throughout the neuraxis with some minor differences in the severity and distribution of lesions.1,10

PHEV, the only neurotropic porcine coronavirus, causes "vomiting and wasting disease" and/or encephalomyelitis in piglets less than 4 weeks of age, generally in 1-3 week-old piglets. It causes a nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis with neuronal degeneration involving predominantly the grey matter of the brainstem and proximal spinal cord.2,6

Although it is a systemic infection, PRRS has rarely been reported to cause predominantly central nervous system (CNS) lesions and clinical signs (neuroinvasive/ neurovirulent).3,8 Lesions described in the CNS are lymphohistiocytic encephalitis (grey and white matter), with or without vasculitis, and/or meningitis;3,9 in published reports we found, the spinal cord has apparently not been examined. Neuronal degeneration/ necrosis is not however a feature even in these cases and PRRSV is not considered a neuronotropic virus, although it was detected in neurons in one case.3,7 PRRS is a common disease in Quebec and a generally mild lymphohistiocytic meningitis and/or encephalitis is often present along with the classical interstitial pneumonia and other lesions (e.g. lymphohistiocytic interstitial myocarditis).

PCV-2 also causes a systemic infection that results in a spectrum of diseases known as "porcine circovirus disease" (PCVD) or "porcine circovirus-associated disease" (PCVAD), the best known being postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS). CNS lesions are reported in PCVAD, but the role of PCV-2 is often not clear; they are generally mild and non-specific, e.g. nonsuppurative encephalitis and/or meningitis.2,4,8 Neurological disease has rarely been reported with PCV-2 infection; in these cases, reported CNS lesions include cerebellar vasculitis and granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis with multinucleated cells. These lesions were seen concurrently with systemic lesions typical of PMWS (e.g. widespread lymphoid depletion with granulomatous inflammation).4,8

Other possible causes of nonsuppurative polioencephalitis ± myelitis in pigs include rabies (Lyssavirus), pseudorabies (suid herpes 1/varicellovirus; not present in Canada), West Nile virus (flavivirus) infection and "blue eye disease" (rubelavirus; Mexico). Although it is called encephalomyocarditis (cardiovirus), this disease is mainly a necrotizing myocarditis with generally minimal CNS lesions.2,10

Contributing Institution:

Faculty of veterinary medicine, Université de Montréal: https://fmv.umontreal.ca/faculte/departements/pathologie-et-microbiologie

JPC Diagnosis: Spinal cord, grey matter: Poliomyelitis, lymphocytic, diffuse, marked with neuronal necrosis, neuronophagia, glial nodule formation, and meningitis.

JPC Comment: The contributor provided an excellent review of neuronotropic viruses that target the spinal cord in swine.

Porcine sapelovirus is a member of the family Picornaviridae and was previously known as porcine enterovirus-8. There are historically two other species within the sapeloviruses, an avian species with one serotype and a simian species with three, hence the name ?sapelovirus? for simian, avian, and porcine entero-like viruses. More recently, the avian virus was moved to the genus Anativirus, and sapeloviruses have been discovered in the fecal flora of the sea lion and of a house mouse.11

Porcine

sapelovirus has been identified in the feces of both healthy and diseased swine

around the world.5 It may result in SMEDI-like fetal mortality if

inoculated into gilts on day 30 of gestation or earlier. In addition to

neurologic disease, it may result in pneumonia and diarrhea as well. Histologic

lesions in the intestine are those of villous atrophy.5

While most commonly transmitted by fecal-oral contact, this virus is

environmentally resistant, and may also be transmitted through fomites.

Diarrheic disease is seen intially in experimentally inoculated 50- to 60-day-old

pigs, which is followed by ataxia and paraparesis and ultimately paralysis

approximately five days later. Death occurs in an additional 2-3 days due to

encephalitis. Humoral immunity is important in protection against sapelovirus

infection, with maternal colostrum and early IgA production being considered

protective against infection in weanlings.5

The moderator reviewed a number of viral and nutritional/toxic possibilities for lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord.

References:

1. Arruda PH, Arruda BL, Schwartz KJ, et al. Detection of a novel sapelovirus in central nervous tissue of pigs with polioencephalomyelitis in the USA. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64(2):311-315.

2. Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer?s Pathology of domestic animals, vol.1. Sixth Edition. Elsevier. St.Louis, MO, 2016:250-406.

3. Cao J, Li B, Fang L, et al. Pathogenesis of nonsuppurative encephalitis caused by highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24(4):767-71.

4. Drolet R, Cardinal F, Houde A, et al. Unusual central nervous system lesions in slaughter-weight pigs with porcine circovirus type 2 systemic infection. Can Vet J. 2011;52(4):394-7.

5. Horak S, Killoran K, Leedom Larson KR. Porcine sapelovirus. Swine Health Information Center and Center for Food Security and Public Health, 2016. http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/pdf/shicfactsheet-porcine-sapelovirus.

6. Mora-Díaz JC, Piñeyro PE, Houston E, et al. Porcine Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis Virus: A Review. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:53.

7. Salles MW, Scholes SF, Dauber M, et al. Porcine teschovirus polioencephalomyelitis in western Canada. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23(2):367-73.

8. Seeliger FA, Brügmann ML, Krüger L, et al. Porcine circovirus type 2-associated cerebellar vasculitis in postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS)-affected pigs. Vet Pathol. 2007;44(5):621-34.

9. Thanawongnuwech R, Halbur PG, Andrews JJ. Immunohistochemical detection of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus antigen in neurovascular lesions. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1997;9(3):334-7.

10. Vandevelde M, Higgins RJ, Oevermann A. Inflammatory diseases. In: Veterinary Neuropathology. First Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. Chichester, West Sussex, 2012:48-80.

11. Murine sapelovirus. https://www.picornaviridae.com/sapelovirus/msv/msv.htm