WSC 22-23

Conference 2

CASE IV: 2019 NHP (JPC 4140673)

Signalment:

19-year-old intact female rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta)

History:

Several week history of inappetence, weight loss, and chronic non-regenerative hypochromic and microcytic anemia.

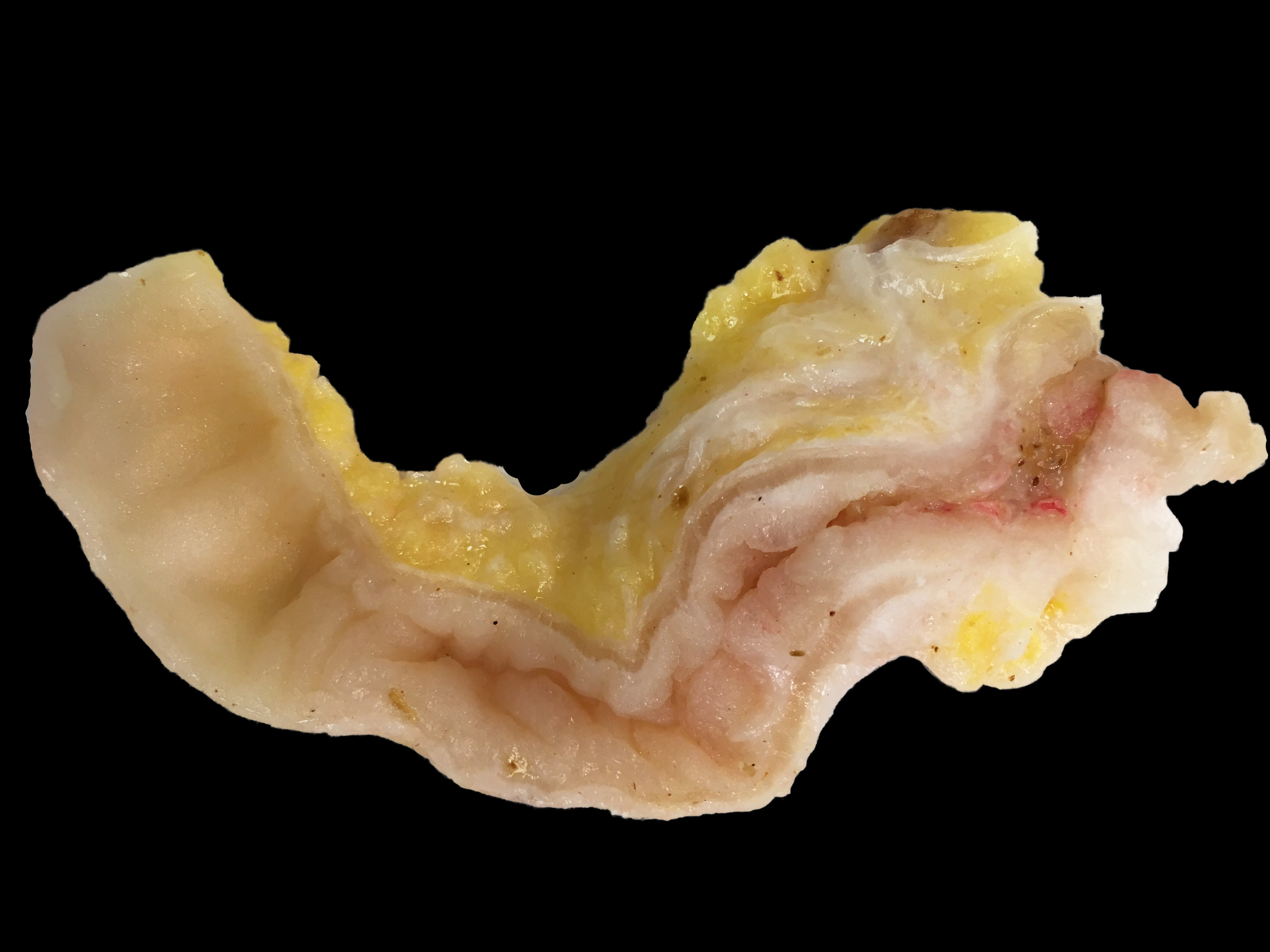

Gross Pathology:

The abdominal cavity contained ~1 liter of serosanguinous fluid. The mesentery and abdominal visceral serosa contain too numerous to count, multifocal-to-coalescing, pale tan-to-white, slightly raised, firm coalescing nodules ranging from 1-4 millimeters in diameter. The distal 2 cm of the ileum and proximal 1 cm of the paired ceca and colon are infiltrated and effaced by a poorly demarcated, highly infiltrative neoplasm. On cut surface, the lumen of the distal ileum is severely stenotic, with loss of normal intestinal mural stratification.

Laboratory Results:

Repeated CBC results indicated a chronic progressive hypochromic and microcytic non- anemia.

|

CBC Parameters |

||

|

WBC (K/uL) |

13.6 |

7.72-9.17 |

|

RBC (M/uL) |

5.3 |

6.24-6.73 |

|

HGB 9G/dL) |

5.7 |

12.03-12.95 |

|

HCT (%) |

22.2 |

41.90-44.77 |

|

MCV (fL) |

42 |

66.02-68.02 |

|

MCH (pg) |

10.8 |

18.84-19.81 |

|

MCHC (g/dL) |

25.7 |

28.32-29.29 |

|

Reticulocyte (%) |

4.9 |

1.44+/-0.46 |

|

Absolute Reticulocyte (K/uL) |

260 |

79.8+/-24.3 |

|

Nucleated RBC (/100 WBC) |

None seen |

|

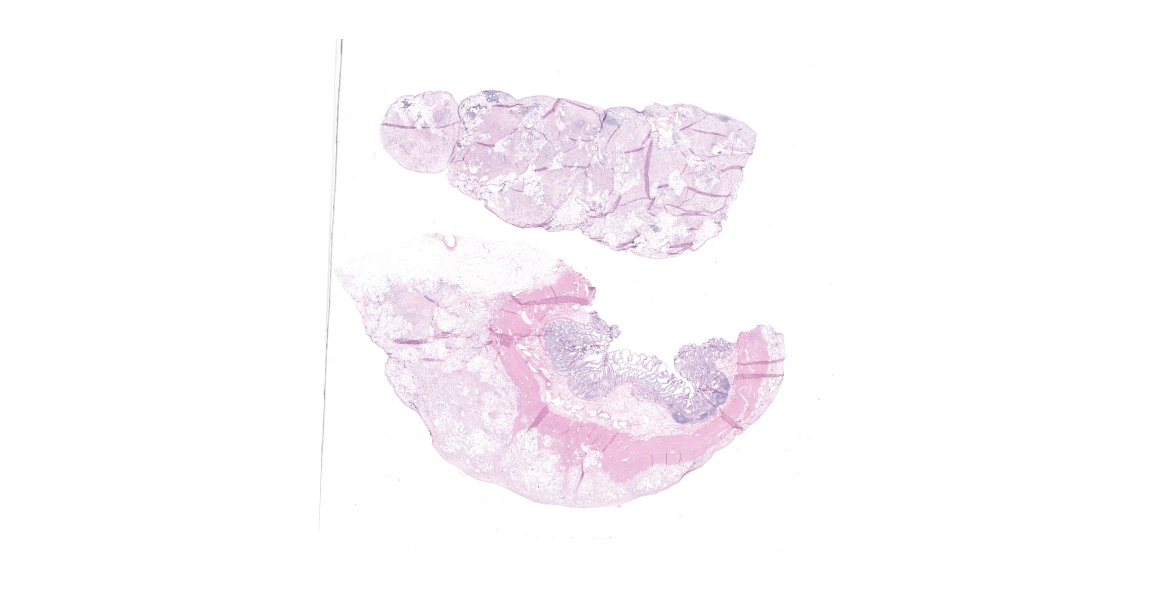

Microscopic Description:

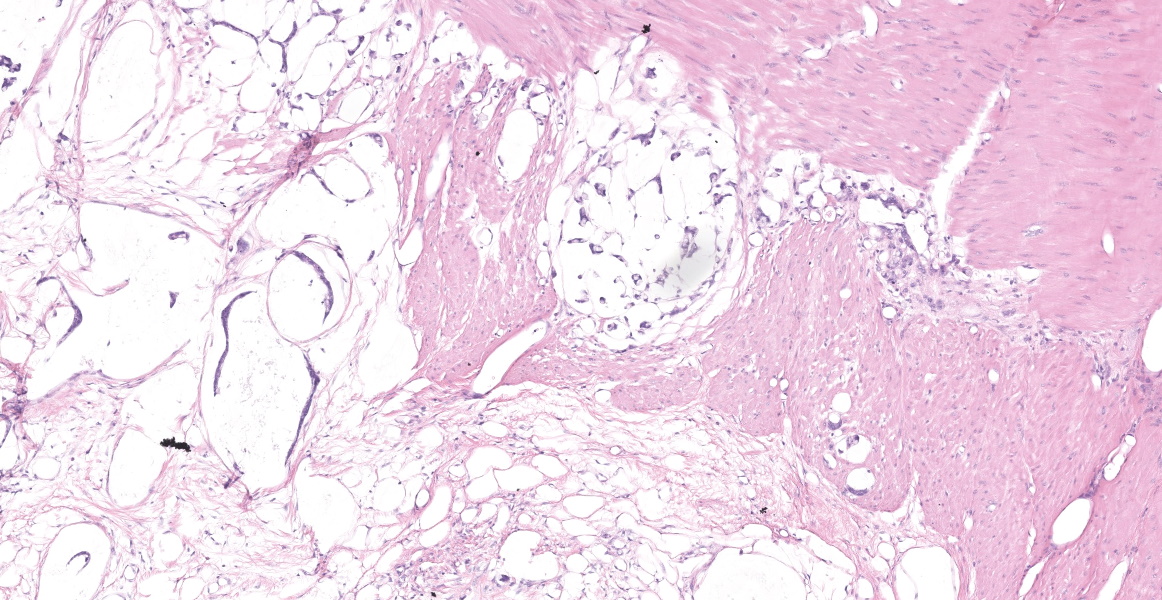

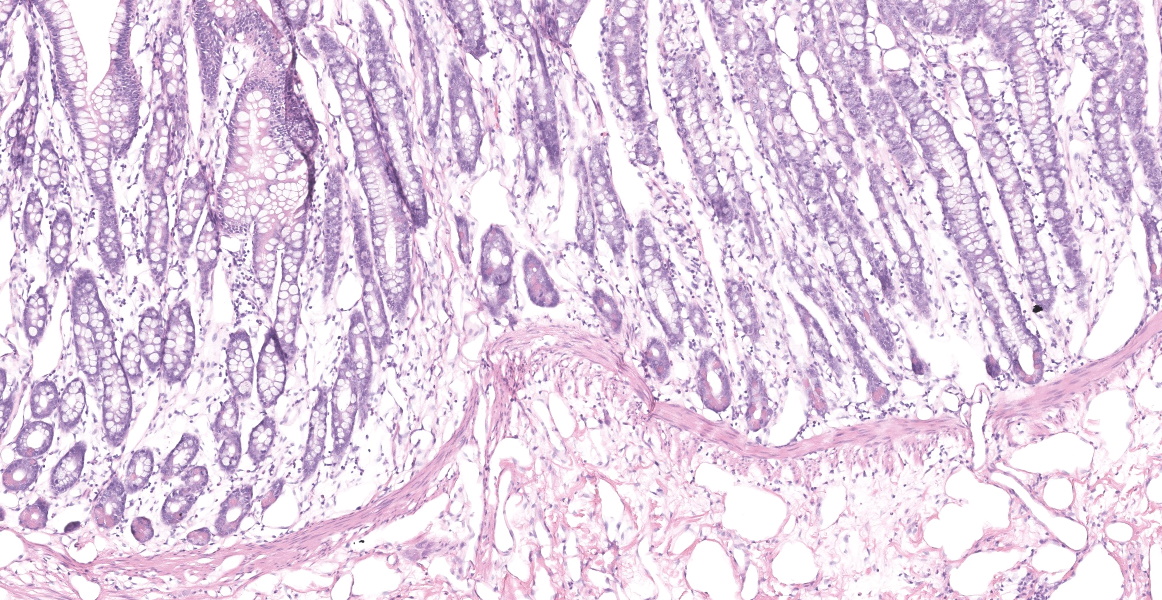

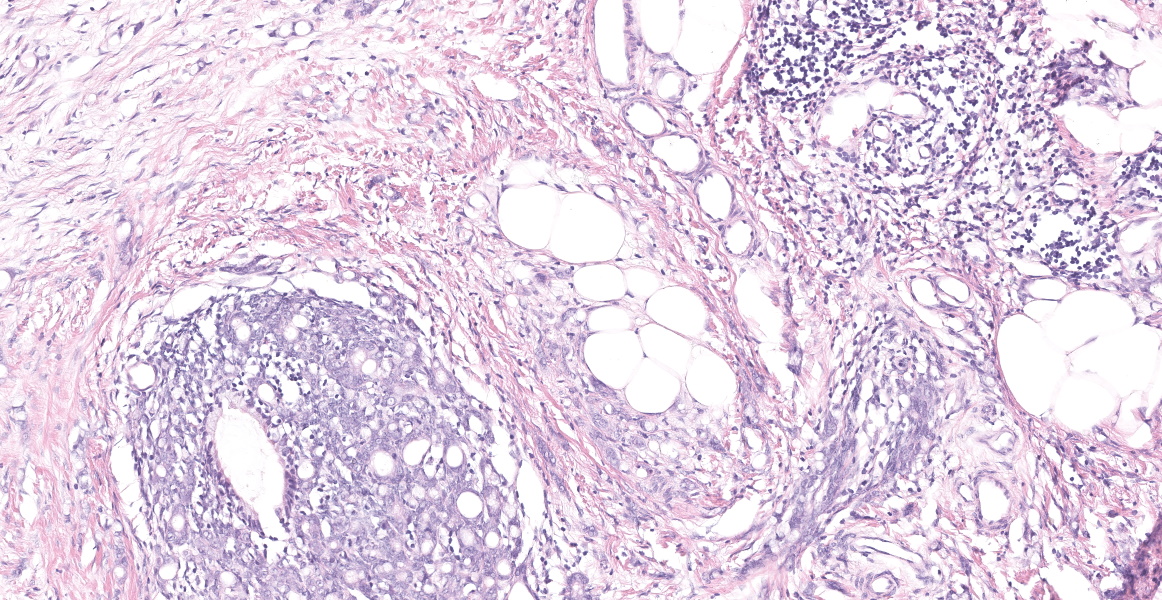

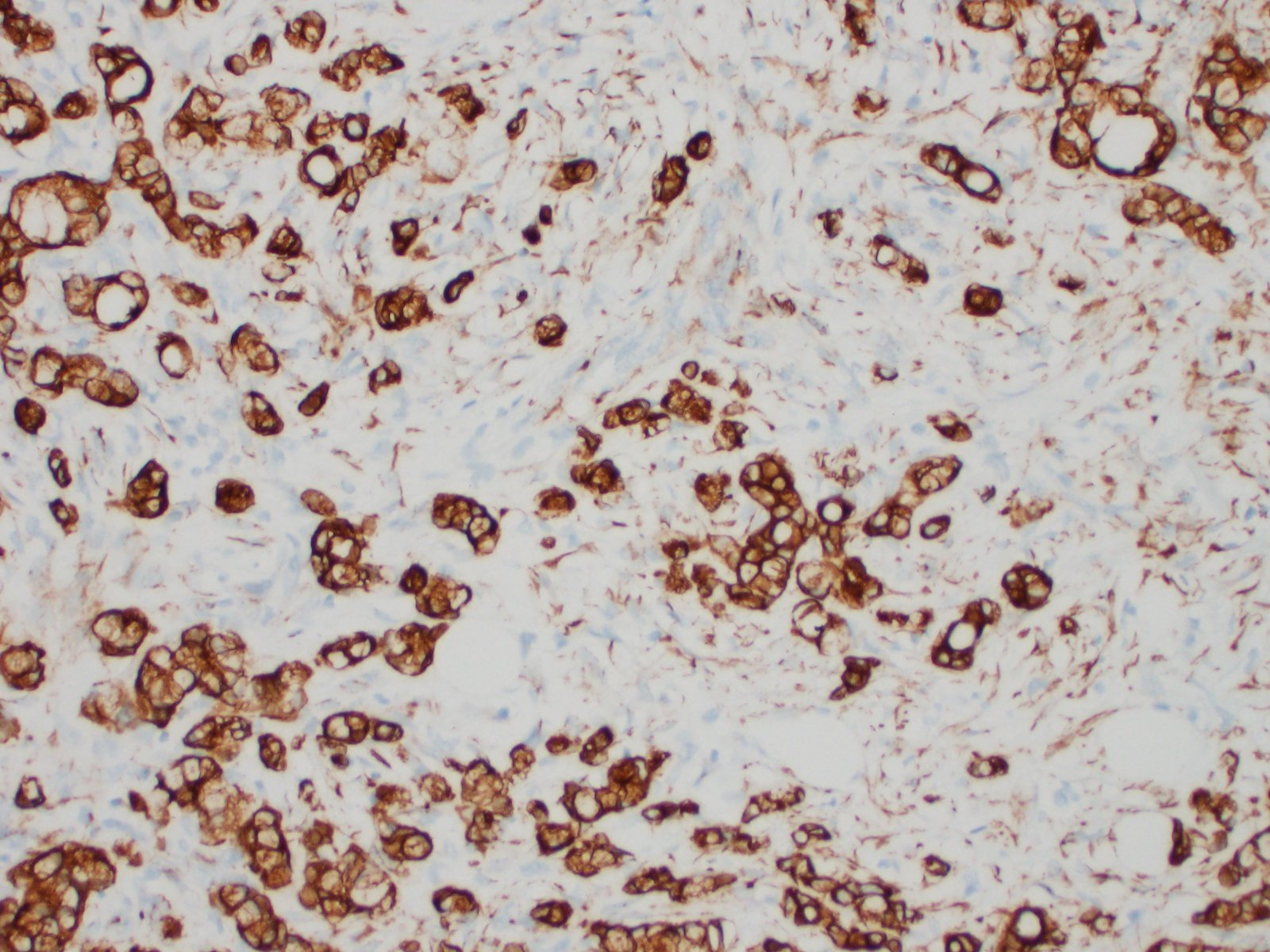

Distal ileum: In the sections submitted the submucosa, muscularis and serosa are multifocally effaced by an unencapsulated, poorly circumscribed, low-to-moderately cellular, infiltrative, highly pleomorphic epithelial neoplasm. Neoplastic cells are cuboidal-to-columnar and form both tubules and acini, with occasional formation of variably sized mucinous lakes surrounded by dense fibrous connective tissue stroma (desmoplasia). Formation of signet ring cells (epithelial cell with a large, clear cytoplasmic vacuole that peripheralizes the nucleus) is occasionally observed. Stroma is infiltrated by lymphocytes and lesser numbers of histiocytes. Neoplastic cells exhibit marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, have variably distinct cells borders and a moderate amount of granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are round to oval with one or two distinct nucleoli. The mitotic rate ranges from 1-4/HPF. Transmurally lymphatics are markedly ectatic (lymphangiectasia) as indicated by large clear spaces neoplastic cells display cytoplasmic immunoreactivity to pancytokeratin supportive of epithelial origin.

Mesentery: Similar neoplastic epithelial cells as described infiltrating the wall of the ileum efface and expand the mesentery, with scattered patches of retained adipocytes and mesenteric blood vessels.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnosis:

Ileocecocolic junction adenocarcinoma (scirrhous, mucus producing) with lymphangiectasia, and abdominal carcinomatosis

Contributor's Comment:

In humans, gastrointestinal carcinomas are relatively common, but most of these arise in the colon and rectum with only a small percentage in the small intestine and ileum.1 Furthermore, large intestinal neoplasia in the rhesus macaque is believed to be significantly different from that in humans due to the absence of polyp formation, although there are similarities in histologic appearance and immunohistochemical characteristics.1 In contrast, the ileocolic junction is considered a common site for intestinal adenocarcinomas in aged rhesus macaques and has also be described in the duodenum, jejunum, distal ileum, cecum, and colon.1,5,10 Cotton-top marmosets are unique among NHPs as they often develop adenocarcinomas in response to chronic inflammation of the colon, including the cecum, colon, and rectum.1 The most commonly reported site of metastasis of intestinal adenocarcinoma in NHPs is the regional mesentery lymph nodes, with colonic and thoracic lymph nodes, peritoneum, diaphragm, intercostal muscles, kidneys, adrenal glands, liver, lung, and spleen also having been reported.1,5 Representative specimens of the mesentery and intestinal neoplasm were the only tissues submitted for histopathologic examination from this case and thus we cannot rule out the possibility of previously described metastatic locations.

Surgical excision with intestinal resection and anastomosis remains the preferred treatment for intestinal adenocarcinoma in rhesus macaques. In a review article of the WNPRC breeding colony, 12% (3 of 25) of animals with surgical resection of intestinal adenocarcinomas were alive, with a mean survival time of 1.5 years.1 The other 22 of 25 animals were euthanized due to deterioration of clinical health. Following necropsy of these animals, surgical excision was determined to be curative in 55% (12 of 22) of cases with no gross or histologic evidence of recurrence at the time of necropsy.

This case of ileocecocolonic adenocarcinoma is particularly impressive given that there was severe mesenteric and peritoneal seeding (carcinomatosis) that resulted in occlusion of lymphatics and subsequent lymphangiectasia. Neither a serum iron concentration or a fecal occult blood test were conducted in this case, but it is reasonable to attribute the chronic microcytic hypochromic anemia to a combination of G.I. hemorrhage, chronic inflammation resulting in sequestration of iron stores, as well as malabsorption due to the lymphangiectasia.

Contributing Institution:

Boston University School of Medicine, National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory (http://www.bu.edu/neidl/)

JPC Diagnosis:

Ileocecocolic junction and mesentery: Mucinous adenocarcinoma.

JPC Comment:

Ileocecocolic adenocarcinoma is the most common gastrointestinal neoplasm in rhesus macaques and has also been reported in Japanese and cynomolgus macaques.9 Clinical signs include weight loss, inappetence, bloating, hematochezia, and decreased fecal volume. Grossly, the annular appearance of intestinal adenocarcinoma may mimic chronic cicatrizing ulcerative colitis, an uncommon condition in macaques which also affects the cecum and colon and causes distension of the proximal intestinal segments.6 These neoplasms invade transmurally and incite a pronounced desmoplastic response.9 Prominent infiltrates of lymphocytes within and surrounding the tumor may be present.4 In the mucinous subtype, which accounts for 25% of colonic adenocarcinomas in rhesus macaques, neoplastic cells produce abundant mucin which may impart a bubbly appearance grossly; histologically, neoplastic cells may accumulate mucin intracellularly, producing the signet ring appearance, or they may produce extracellular lakes of mucin which cause attenuation of surrounding cells. 4,6,10

As the contributor stated, ileocecal/colonic adenocarcinomas in rhesus macaques differ from similar neoplasms in humans by the lack of polyp formation; however, a recent study suggests that at least one colony of rhesus macaques may be a suitable model for a certain type of hereditary colorectal cancer in humans.4 Lynch syndrome, which can cause hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) in humans, is characterized by damage in any of the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, or PMS2. 4 Humans with Lynch syndrome have higher risks of various neoplasms at a younger age, including neoplasms of the colon, endometrium, stomach, and small intestine. 4 Lynch syndrome can be diagnosed through identification of microsatellite instability, a phenomenon where unrepaired DNA errors occur in certain short repetitive DNA segments (microsatellites) due to MMR gene defects. Additionally, immunohistochemical staining can illustrate decreased reactivity of the MMR proteins in neoplastic cells. In a study of 60 spontaneous cases of colorectal cancer in one closed colony of rhesus macaques, 17 of 20 tested animals lacked MLH1 and PMS2 immunoreactivity, and 6 of 9 tested animals demonstrated microsatellite instability.4 Whole genome sequencing also revealed strong association of colorectal cancer and mutations in MLH1 and MSH6 genes.4 This study indicates that this colony of rhesus macaques could potentially supply investigative avenues for a human disease where current animal models are lacking.

References:

- Beart RW, et al. Management and survival of patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum: a national survey of the Commission on Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 1995; 181(3): 225-36.

- Chalifoux LV, Bronson RT. Colonic adenocarcinoma associated with chronic colitis in cotton top marmosets, Saguinus oedipus. Gastroenterology. 1981; 80(5 pt 1): 942-946.

- DePaoli A, McClure HM. Gastrointestinal neoplasms in nonhuman primates: a review and report of eleven new cases. Vet Pathol. 1982; 19 (Suppl 7): 104-125.

- Dray BK, Raveendran M, Harris RA. Mismatch repair gene mutations lead to lynch syndrome colorectal cancer in rhesus macaques. Genes & Cancer. 2018; 9(3-4): 142-152.

- Harbison CE, et al. Immunohistochemical Characterization of Large Intestinal Adenocarcinoma in the Rhesus Macaque (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol. 2015; 52(4): 732-40.

- Johnson AL, Keesler RI, Lewis AD, Reader JR, Laing ST. Common and Not-So-Common Pathologic Findings of the Gastrointestinal Tract of Rhesus and Cynomolgus Macaques. Tox Pathol. 2002; 50(5): 638-659.

- Kerrick GP, Brownstein DG. Metastatic large intestinal adenocarcinoma in two rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2000; 39(4): 40-42.

- Lang CD, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the ileocolic junction and multifocal hepatic sarcomas in an aged rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta). Comp Med. 2013. 63(4): 361-366.

- Miller AD. Neoplasia and Proliferative Disorders of Nonhuman Primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfied K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. Vol 2. 2nd Waltham, MA: Elsevier; 2012: 325-356.

- Simmons HA. Age-Associated Pathology in Rhesus Macaques (Macaca mulatta). Vet Pathol. 2016; 53(2): 399-416.