WSC 2023-2024 Conference 7 Case 4

Signalment:

8-year-old, female spayed boxer, canine (Canis familiaris).

History:

The patient was referred to Auburn University Dermatology specialty service for a disease affecting all claws of all four paws with a clinical duration of approximately six months. Affected claws were misshapen,fractured, and ranged from soft to brittle. No systemic abnormalities were reported at the time of admission.

Gross Pathology:

Multiple claws had moderate paronychia characterized by edema, erythema, congestion, and purulent to hemorrhagic exudate at the claw fold with keratinous debris around the claw. All claws had moderate to severe onychodystrophy characterized by onychorrhexis, onychomalacia, onycholysis, onychogryphosis, onychauxis, and onychoschizia. An onychobiopsy without onychectomy employing the technique described by

Mueller and Olivry (1999) was performed and samples were sent for histopathology and fungal culture.

Laboratory Results:

Claw tissue submitted for fungal culture was negative for dermatophytes.

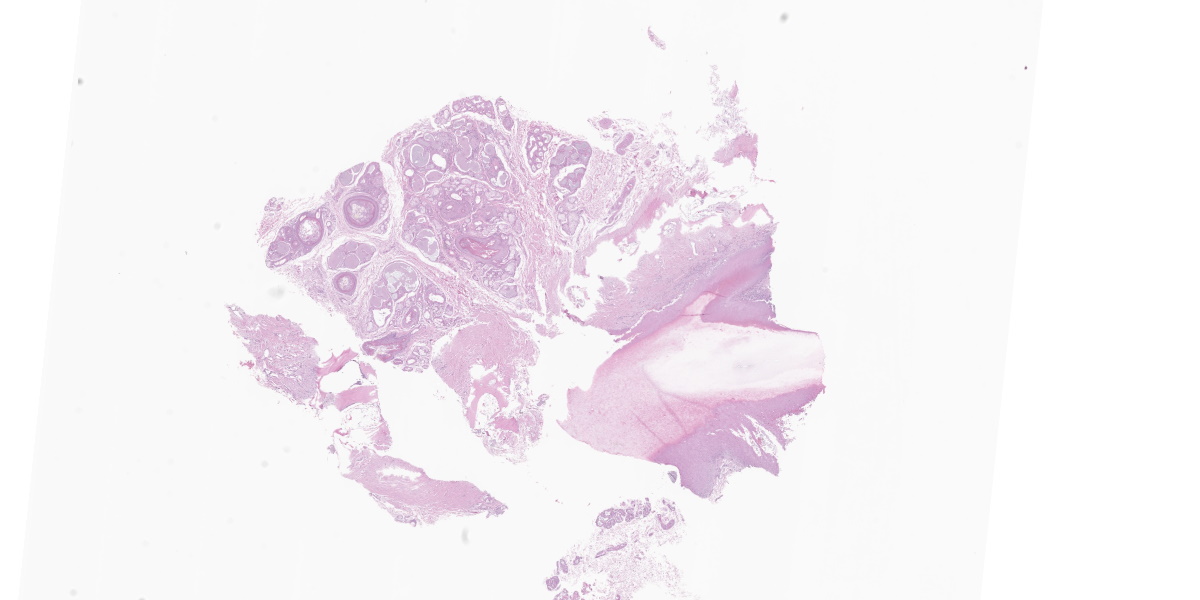

Microscopic Description:

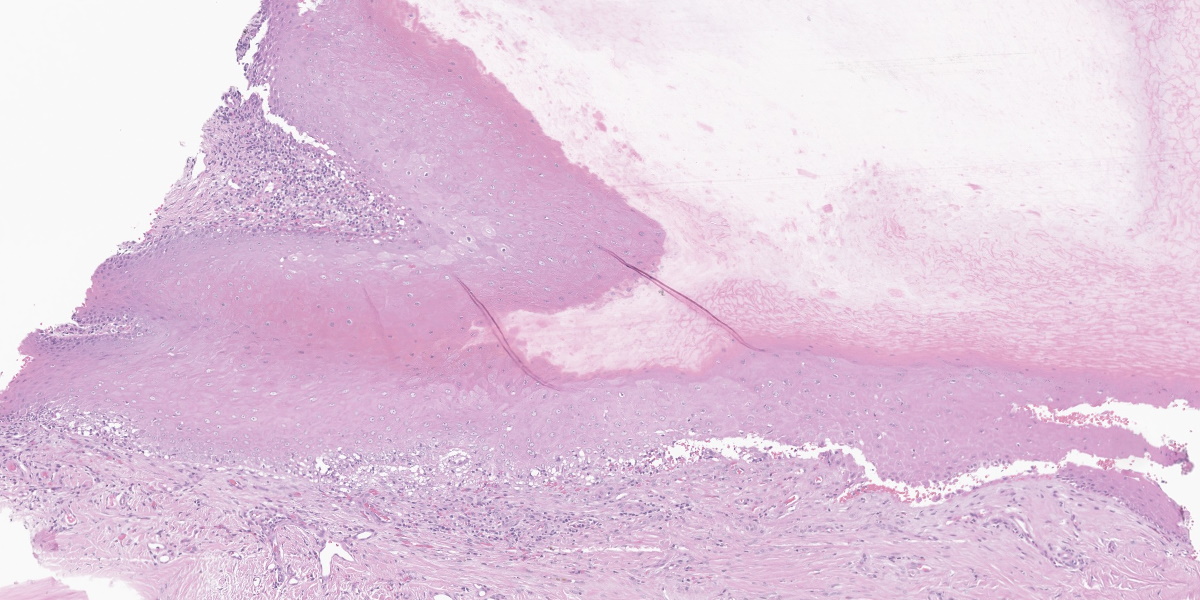

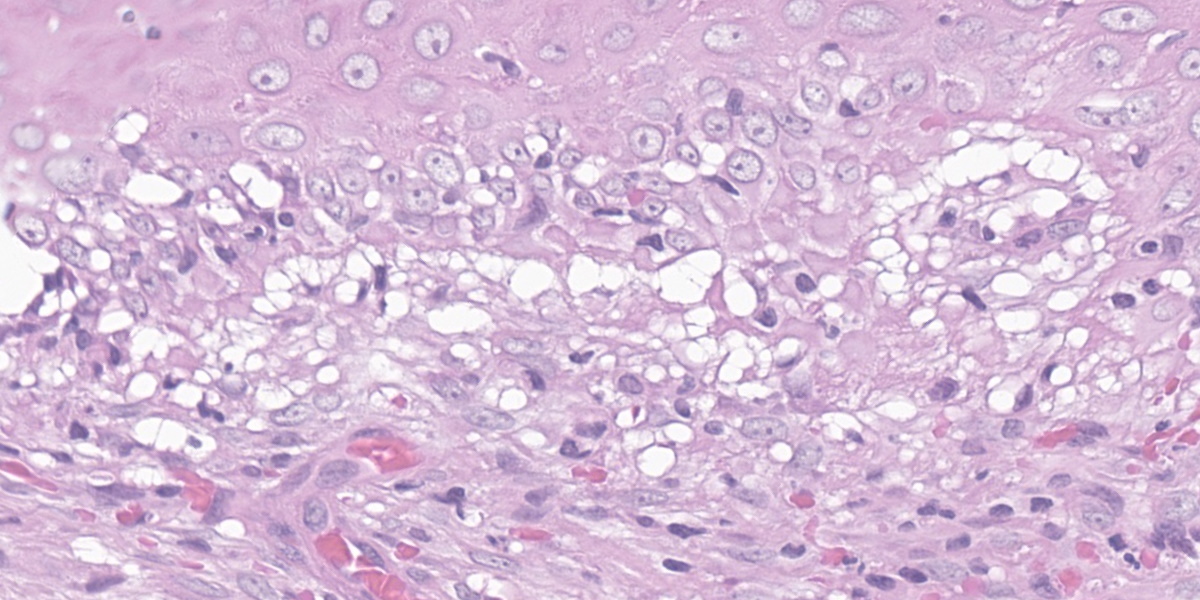

Affecting the claw bed, the dermo-epidermal junction is blurred by a band-like infiltrate composed of moderate numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, fewer neutrophils, and melanin-laden macrophages (pigmentary incontinence). At these segments and other less inflamed epidermal stretches, the basal epithelium is markedly vacuolated and interspersed with individualized, shrun-ken hypereosinophilic keratinocytes with pyknotic nuclei (apoptosis). The superficial dermis is minimally replaced by a smudgy collagenous matrix. Eccrine glands are mildly ectatic, filled with amphophilic product, and surrounded by mixtures of similar inflammatory infiltrates within increased concentric bands of fibrous tissue.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Claw to claw base/bed (digit unspecified): Dermatitis, interface and lichenoid, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, moderate, with pigmentary incontinence, basal epithelial vacuolation, and apoptosis (consistent with symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy).

Contributor’s Comment:

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Onychodystrophy |

Abnormal claw formation |

|

Paronychia |

Inflammation or infection of the claw folds |

|

Onychomalacia |

Softening of the claws |

|

Onycholysis |

Separation of the claw from the underlying corium but with continuing proximal attachment |

|

Onychogryphosis |

Hypertrophy and abnormal curvature of the claws |

|

Onychauxis |

Hypertrophy of the claws |

|

Onychoschizia |

Splitting or lamination of claws, usually beginning distally |

|

Onychalgia |

Claw pain |

|

Onychomadesis |

Sloughing of the claws (claw shedding) |

|

Table 4-1. A sampling of claw disorder terminology. Table adapted from Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. 2012. |

|

Symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy (SLO), also known as symmetric lupoid onychitis, is an uncommon primary ungual disease that has been described in dogs.1,4,6 This condition may occur in dogs of all ages; however, young to middle-aged dogs appear to be more commonly affected.4 Certain breeds seem to be predisposed, including German Shepherd and Gordon Setter; nevertheless, SLO has been reported in numerous breeds, and sex predisposition has not been described.1,4,9

SLO lesions are restricted to the claws and affected dogs are usually otherwise healthy with no systemic involvement.1 Typically, the first clinical signs observed by owners are licking of the paws and lameness due to onychalgia or onychomadesis.1,4 Paronychia with onycholysis of multiple claws is observed and, within weeks, several or all claws of all paws are affected.1,3 After sloughing, regrown claws are commonly misshapen, brittle, dry, and discolored, and secondary bacterial infections are common.1,4

The cause and pathogenesis of SLO are controversial and have not been completely elucidated.4 In a study with Gordon Setters, dog leukocyte antigen (DLA) class II alleles associated with the disease and negatively correlated with the disease were described, suggesting a genetic predisposition.9 A case series reported the detection of antinuclear antibodies in 3/10 Gordon Setters with SLO, suggesting that SLO may be an auto-immune disease.2 Nevertheless, some authors believe that the histopathological findings of SLO, characterized by lichenoid-interface dermatitis and basal cell vacuolation/damage affecting the claw represent a tissue response pattern to different conditions and not a separate entity.4 For instance, lesions affecting the claws with similar histopathological findings to those of SLO have been reported in cases of leishmaniasis, even when amastigotes were not detected in the affected tissue.3

The diagnosis of SLO is usually based on the clinical presentation with the disease restricted to the claws/digits and typical histological findings.4 Distal onychectomy (third phalanx [P3] amputation) has been considered the gold standard method to diagnose SLO. An alternative technique, onychobiopsy without onychectomy, was employed in this case.5 Through this technique, only a portion of the lateral claw matrix is collected, and no amputation is necessary; however, some downsides include the fact that localized lesions may be missed.5 Other systemic diseases may affect the claws, including systemic lupus erythematosus, hepatocutaneous syndrome, pemphigus vulgaris, and bullous pemphigoid, leading to potentially overlapping gross or microscopic findings; however, other cutaneous or systemic lesions are expected with these diseases.4,7

Several treatments for SLO have been reported with variable success, including supplementation with omega-3 and omega-6 essential fatty acids (EFA), as well as combinations of EFA with other therapies such as topical glucocorticoids, pentoxifylline, and tetracycline/niacinamide.1,4,6 In this case, the patient showed significant clinical improvement after treatment with pentoxifylline, vitamin E, and omega EFAs.

Contributing Institution:

Auburn University

Department of Veterinary Pathobiology

https://www.vetmed.auburn.edu/academic-departments/dept-of-pathobiology/

JPC Diagnosis:

Nailbed: Onychitis, lymphocytic, cytotoxic interface, marked.

JPC Comment:

A clinical history of loss of one or more claws on multiple paws within 2 weeks to a few months after initial onset should suggest a diagnosis of SLO.8 Regrown nails are typically misshapen and friable and will re-slough. The sequence of onychomadesis followed by onychodystrophy is required for an SLO diagnosis and differentiates this condition from idiopathic onychodystrophy of dogs, where there is no onychomadesis preceding onychodystrophy.8 In addition, SLO lesions are restricted to the claw and no skin or mucosal lesions occur.8

The contributor provides an excellent overview of this uncommon condition, and the case presented here is characteristic of the disease. The examined slide exhibits the typical histologic features of SLO - lymphocytic interface dermatitis with basal cell vacuolation, apoptosis, and pigmentary incontinence – though the interface dermatitis can vary widely in severity.8 Typical histologic findings may also be found in conjunction with superimposed bacterial infections and osteomyelitis.8 These histologic findings are relatively non-specific and can be found in a variety of diseases of the canine claw, making clinical history paramount in the diagnosis of this condition.

The moderator began by reviewing claw anatomy and the specialized terminology used to describe nail pathology (see Table 4-1). The moderator emphasized that SLO requires lesions in all paws and (almost) all claws; if a patient has the same clinical presentation but with only one affected nail, the moderator would prioritize onychomycosis as a differential diagnosis. The moderator uses a PAS stain to rule in or out onychomycosis as fungal elements are largely impossible to visualize on H&E sections of the claw.

Several participants questioned whether the clefting noted in the examined section is real or artifactual. While clefting can be an artifact caused during tissue collecting and processing, it can also be real and diagnostically helpful since clefting at the epidermal-dermal junction would be expected to occur in this condition. The moderator believes that the clefting present in this section is real due to the hemorrhage and cellular debris present within the cleft. The moderator also noted that the examined section is an exceptional example of cytotoxic interface dermatitis. The moderator showed more typical examples with less florid inflammatory infiltrates and less affected basilar epithelium.

The JPC morphologic diagnosis was once again whittled down to the essentials. While the original morphologic diagnosis contained many of the same histologic features enumerated in the contributor’s diagnosis, conference participants felt that many of the terms, such as basilar cell vacuolation, apoptosis, and pigmentary incontinence, were subsumed within the term “cytotoxic interface onychitis.” The resulting morphologic diagnosis is zippy, accurate, and mercilessly brief.

References:

- Auxilia ST, Hill PB, Thoday KL. Canine symmetrical lupoid onychodystrophy: a retrospective study with particular reference to management. J Small Anim Pract. 2001;42:82-87.

- Bohnhorst JO, Hanssen I, Moen T. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in gordon setters with symmetrical lupoid onychodystrophy and black hair follicular dysplasia. Acta Vet. Scand. 2001;42(3): 323-329.

- Koutinas AF, Carlotti DN, Koutinas C, et al. Claw histopathology and parasitic load in natural cases of canine leishmaniosis associated with Leishmania infantum. Dermatol. 2010;21:572-577.

- Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Diseases of eyelids, claws, anal sacs, and ears. In: Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL, eds. Muller and Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2012:724-773.

- Mueller RS, Olivry T. Onychobiopsy without onychectomy: description of a new biopsy technique for canine claws. Dermatol. 1999;10:55-59.

- Mueller RS, Rosychuck RAW, Jonas LD. A retrospective study regarding the treatment of lupoid onychodystrophy in 30 dogs and literature review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003;39:139-150.

- Stern AW, Pieper J. Pathology in Practice. JAVMA, 2010;246:197-199.

- Welle MM, Linder KE. The Integument. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. 2022;Elsevier:1244.

- Wilbe M, Ziener ML, Aronsson A, et al. DLA class II alleles are associated with risk for canine symmetrical lupoid onychodystropy (SLO). Plos One. 2010;5: e12332.