Signalment:

Gross Description:

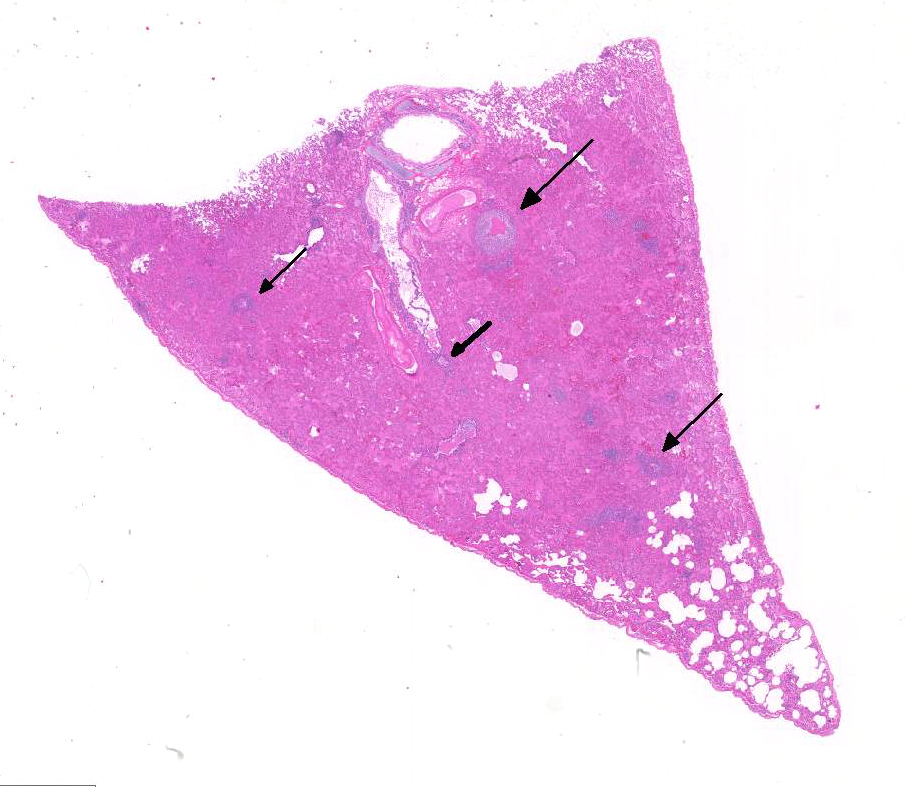

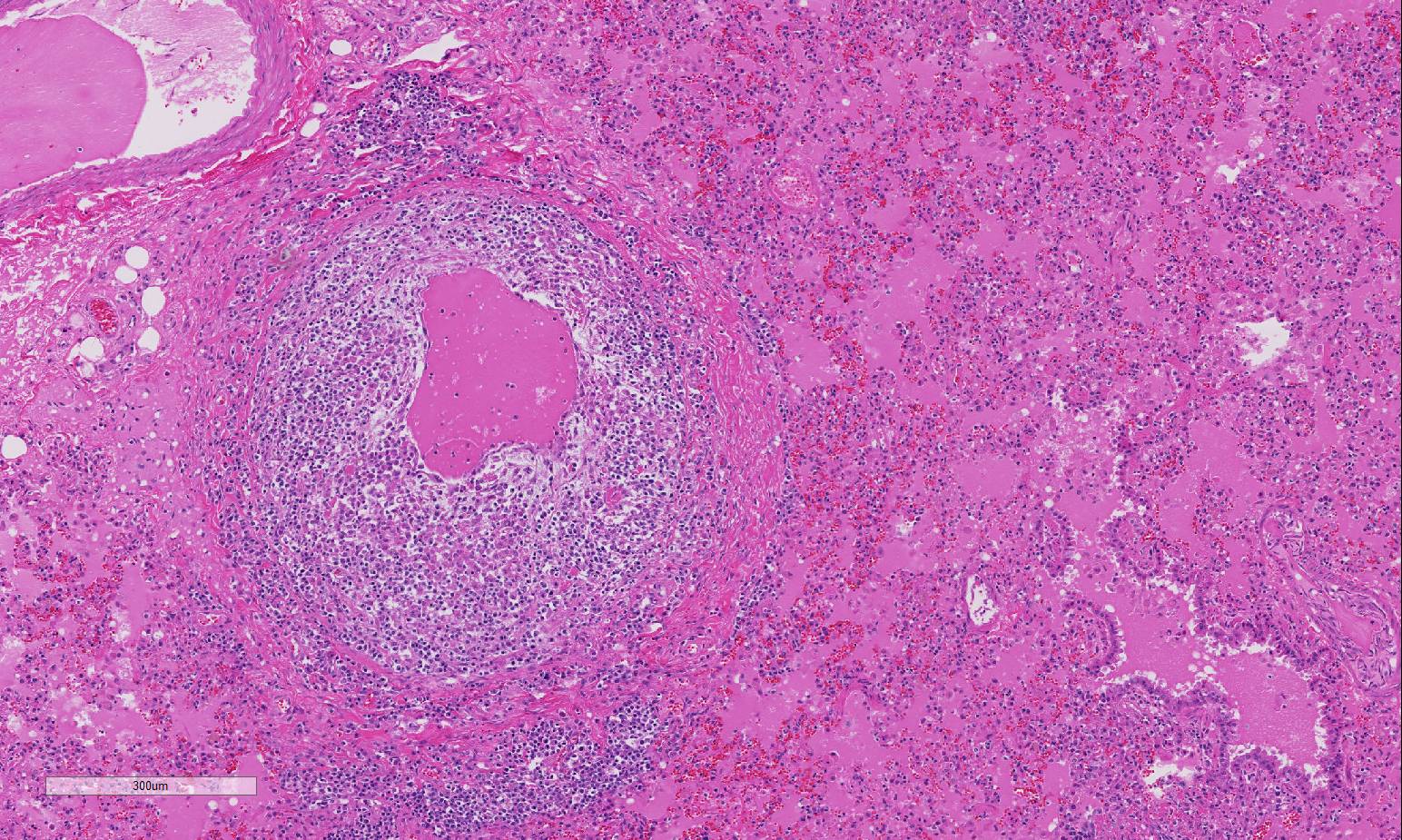

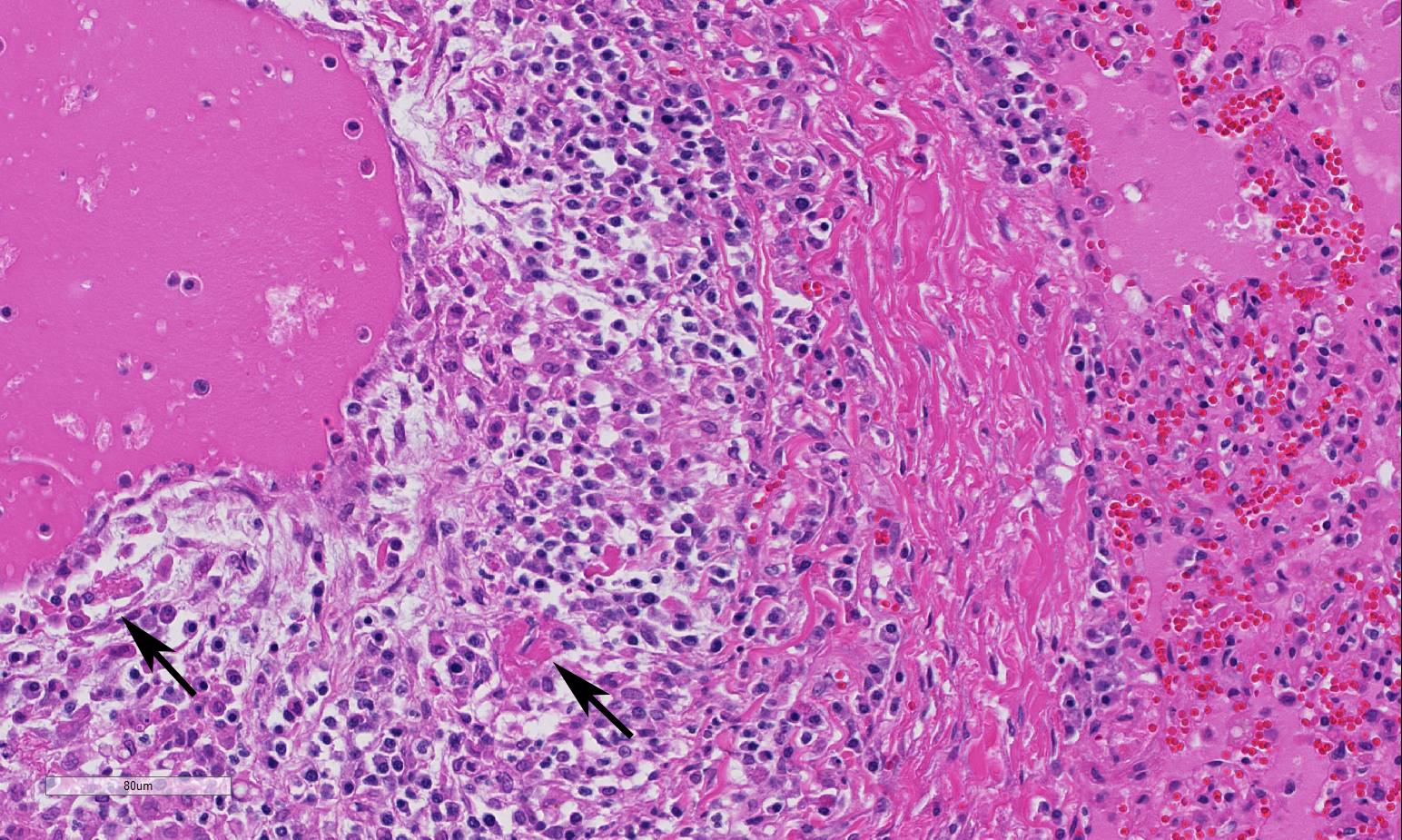

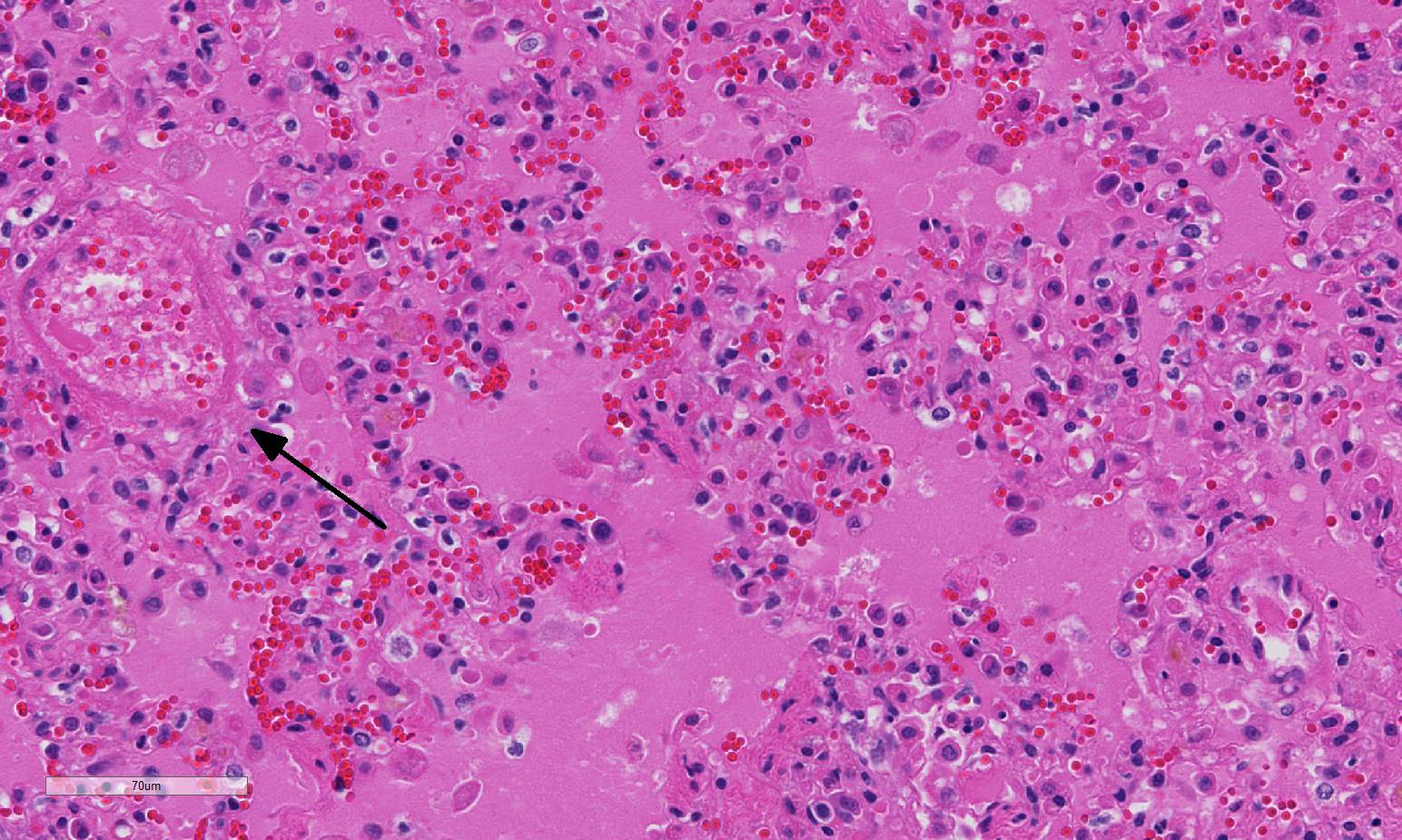

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

FIP is one of the leading infectious causes of death in cats from shelters and catteries.7 FIP is caused by infection with feline coronavirus (FeCoV) that has mutated to become a pathogenic virus (FIPV). FCoV infections are very common, with up to 90% seropositivity in cats, while FIP morbidity is low, rarely above 5% of infected cats. Most infections with feline coronavirus are sub-clinical, although mild diarrhea and vomiting can occur. The FCoV mutants that cause FIP are either generated within the individual cat, or possibly are acquired externally.

Persistently infected, healthy carriers are believed to be most important in the epidemiology of FIP.6 Mutation of the FCoV in the carrier animal generates the FIP virus that is capable of replicating in mo-nocyte/macrophages, resulting in tra-nsportation to organs outside of the GI tract, and development of FIP disease. The FCoV mutants also apparently lose their ability to replicate in intestinal epithelium, as they are not recovered from intestinal tissues.2 For this reason, it is believed that cat to cat transmission of FIP virus is infrequent; the virus does not readily infect cats under natural conditions because it does not replicate in enterocytes, even though the virus readily infects cats when they are experimentally inoculated by routes other than oral.

The

host immune response largely dictates the lesions of FIP. The immune response

to FIP virus is presently understood as follows: humoral immunity is not

important for protection while protective immunity is largely cell mediated.7

The type and strength of immunity determines the form that FIP virus

infection will take. Cats that develop FIP will have either the wet or dry form

depending on whether ineffective cell-mediated or humoral immunity dominates

the clinical disease. Strong humoral im-munity with very weak or non-existent

cellular immunity leads to effusive (wet) FIP. With the effusive form, cats

will have up to 1 L of viscous abdominal fluid while pleural effusion is present

in about 25% of cases. Humoral immunity with intermediate cellular immunity

will manifest as the non-effusive FIP (dry form). With the dry form, the

kidneys may be enlarged and nodular with white, firm nodules protruding from

the cortex. Foci of inflammation may also be seen in other organs, including

the liver and pancreas. The gross lesions of wet versus dry formsare often not

distinctly separate, and much overlap occurs. Vasculitis

and perivasculitis characterize the microscopic lesions of FIP. FIP-induced

granulomatous vasculitis occurs in small to medium-sized veins predominantly in

the leptomeninges, renal cortex, and eye, but also frequently in the lung and

liver.4 Vasculitis is characterized as venous and perivenous, macrophage-dominated,

cir-cular infiltrates in small veins, and focal infiltrates in larger veins.

Neutrophils and T cells represented minorities among in-flammatory cells, and B

cells mainly occur as peripheral rims around circular gra-nulomatous

infiltrates. FIP virus-infected monocytes that become activated and emigrate from

vessel lumens into perivenous locations are reported to be unique to the

development of the periphlebitis that occurs. 1.

Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG,

ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol

2. Saunders Elsevier: New York; 2007: 290-293. 2.

Chang HW, deGroot RJ, Egberink HF, Rottier PJM. Feline infectious

peritonitis: Insights into feline coronavirus pathobiogenesis and epidemiology

based on genetic analysis of the viral 3c gene. J Gen Virol. 2010; 91:415-420. 3. Fischer

Y, Sauter-Louis C, Hartmann K. Diagnostic accuracy of the Rivalta test for

feline infectious peritonitis. Vet Clin Pathol. 2012; 41:558-567. 4.

Kipar A, May H, Menger S, Weber M, Leukert W, Reinacher M.

Morphologic features and development of granulomatous vasculitis in feline

infectious peritonitis. Vet Pathol. 2005; 42: 321-330. 5.

Kipar A, Meli ML. Feline infectious peritonitis: Still an

enigma? Vet Pathol. 2014;51(2): 505-526. 6.

Meli M, Kipar A, Muller C, Jenal K. High viral loads despite

absence of clinical and pathological findings in cats experimentally infected

with feline coronavirus (FCoV) type 1 and in naturally FCoV-infected cats. J

Feline Med and Surg. 2004; 6:69-81. 7.

Pedersen NC. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus

infection: 1963-2008. J Feline Med and Surg. 2009; 11:225-258. 8. Pedersen NC. An update on feline infectious peritonitis:

Virology and immunopathogenesis. Vet J. 2014; 201(2):123-132. 9. Eckerle

LD, Becker MM, Halpin RA, Li K, Venter E, et al. Infidelity of SARS-CoV

Nsp14-exonuclease mutant virus replication is revealed by complete genome

sequencing. PLoS Pathog. 2010;(5):e1000896. 10. Kim

Y, Liu H, Galasiti Kankanamalage AC, Weerasekara S, et al. Reversal of the

Progression of Fatal Coronavirus Infection in Cats by a Broad-Spectrum

Coronavirus Protease Inhibitor. PLoS Pathog. 2016; 12(3):e1005531.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Type II FCoVs arose as a consequence of a double recombination between

type I FCoV and CCoV. Along with homologous recombination, the pro-pensity for

frequent variation and mutation of coronaviruses is also based on a high

mutation rate (2.0×10?6 mutations per site per round of replication) and the

sheer size of the genome (2632 kb). 9 As is true with many viruses,

even a single amino acid mutation and/or recombination events can change viral

properties, host range and pathogenicity. Both feline enteric

coronavirus (FECV) and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV) can infect

monocytes, but FIPVs are able to sustainably replicate in much higher numbers.5

However, not all monocytes are permissive to replication of FIPV8

and there is variation in individual cats regarding the susceptibility of

monocytes to infection and replication, which influences disease sus-ceptibility.

It has also been suggested that monocytes may potentially be the cells where

mutation from FECV to FIPV occurs.5,8 The precise genetic and me-chanistic

differences that define changes in viral replication and virulence have not yet

been clearly elucidated, but various proteins such as 3c, S, S1 fusion peptide

and 7a/b, among others, appear to play a role.5,8

In many cases,

these various proteins appear to influence virus infection of, and replication

in, monocytes. At least three key events are known in the development of FIP

including systemic infection with FIPV, effective FIPV replication in monocytes

and activation of those monocytes,5 highlighting the critical role

of the monocyte response in development of FIP. There was conference

discussion around the use of the terms wet and dry forms of FIP. Some

researchers believe these are a temporal continuum, with the latter being a

chronic manifestation, or a post-man-ifestation of the former. The terms are

useful clinically, but we know little about what contributions of the virus

and/or host are the bases of the two types of presentations. Lesion

distribution in cases of FIP is rather consistent although some degree of in-dividual

variation may be observed. Peritoneal involvement was seen in 75% of cases,

often associated with abdominal effusion, and the kidneys, followed by eyes and

brain, were most often affected according to one study, and ocular in-volvement

was frequently bilateral.5 Antemortem diagnosis of FIP can be particularly challenging.

Cytology of ab-dominal effusion suggestive of FIP contains nondegenerate

neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and few plasma cells on a proteinaceous

background.

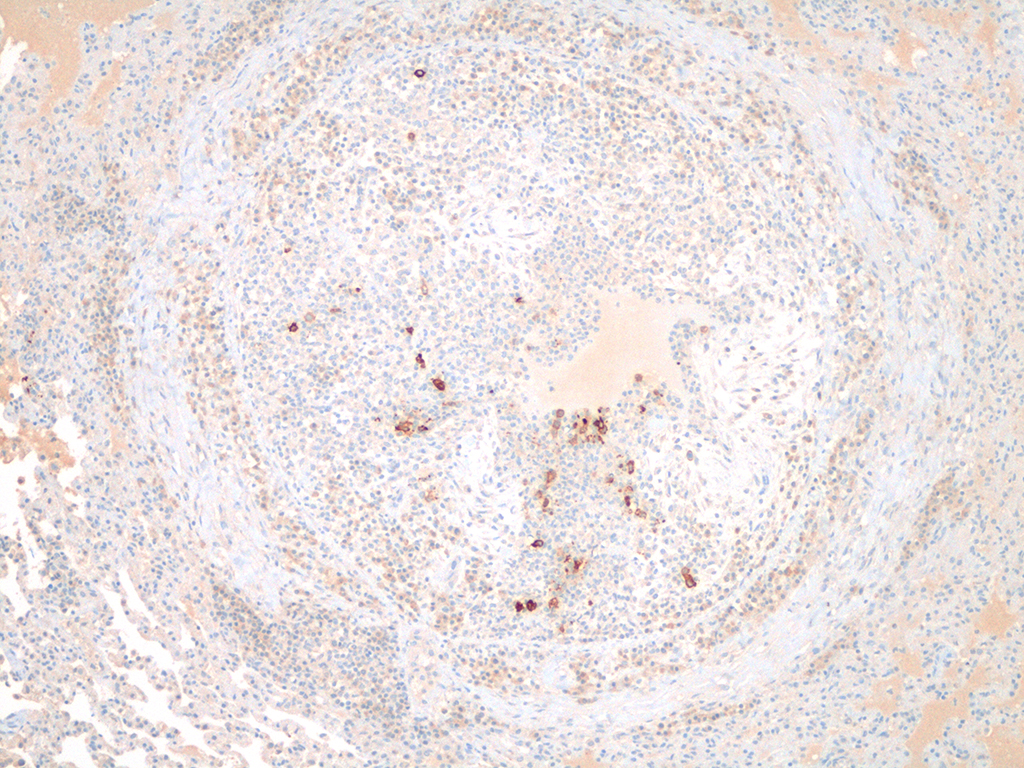

Using imm-unofluorescence or immunohistochemistry to visualize the

virus within monocytes of the effusion is considered diagnostic, excepting

cases of sequestered granulomas, such as this case. A positive reaction in

the Rivaltas test, used to differentiate tran-sudates from exudates, may

increase diagnostic sensitivity when accompanied by cytology of abdominal

effusion.3 As discussed above, vascular lesions are generally

limited to the small and medium sized veins in affected tissues due to

interaction between activated mac-rophages and endothelium.5 In

some cases, vascular lesions, which are generally dominated by macrophages, may

be replaced by B cells and plasma cells.5 This is commonly observed

in ocular disease where plasma cells predominate. The clinical course of

disease in the wet form is generally much faster than for the dry form and

subclinical as well as a protracted or multiphasic course of disease may also

be seen. The conference attendees discussed a recent publication that

demonstrates theoretical reversal of viremia using pro-tease inhibitors, and

clinical trials that are underway to establish whether a rigorous anti-viral

therapy could be helpful.10 Conference participants described the inflammatory infiltrate as

being vascular and perivascular in distribution, effecting small and medium

sized vessels, and remarkably circumferential in most affected vessels. The

loss of vascular architecture included the entirety of the vessel wall which

was markedly thickened by fibrin, both hyalinized and fibrillar, edema, and a

mixed population of inflammatory cells, predo-minantly macrophages. The

endothelium is hypertrophic and vascular lumina are narrowed. The moderator

stressed the importance of describing vascular changes in detail, specifically

with reference to vasculitis; the description should ch-aracterize changes

within each layer of the effected vessel. Edema fluid fills alveoli in this

case, and has refluxed into small and terminal bronchioles, a change which

needs to be distinguished from an airway-centric disease (i.e.,

bronchopneumonia). The alveolar septa and interstitium are mildly expanded by

fibrin and edema. There are multifocal areas of alveolar emphysema and few

areas of mild fibrinous pleuritis.

References: