Signalment:

Gross Description:

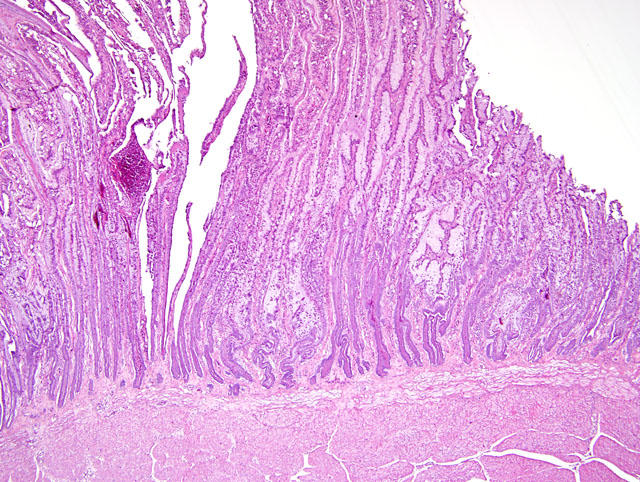

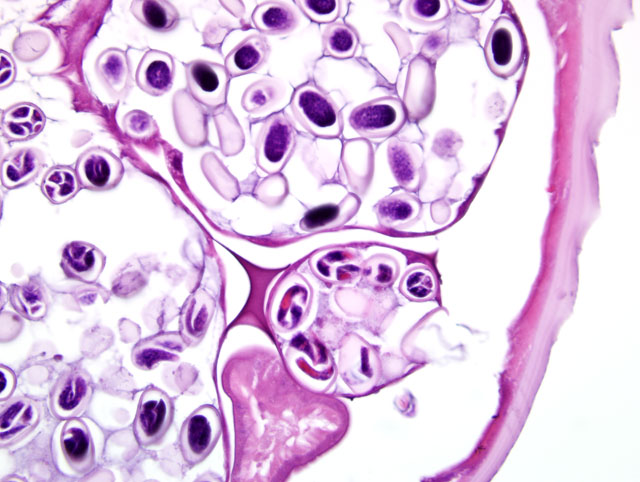

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The life cycle of Dispharynx is indirect utilizing an intermediate terrestrial isopod host. Adult female D. nasuta pass embryonated eggs into the lumen of the proventriculus, which are later shed in the feces.(11) The eggs are consumed by the intermediate host, wood lice (Armadillidium vulgare) or sow bugs (Porcellio scaber), in which the larvae subsequently hatch and penetrate the host tissues. First stage larvae (L1) develop into the infective third stage (L3) within 26 days. The third stage larvae (L3) can survive in the infected intermediate host for up to 6 months. Once the intermediate host is consumed by a susceptible bird the third stage larvae (L3) further develop, reaching sexual maturity in 27 days.(7)

Sexually mature adults primarily infect the proventriculus, though in severe cases they can also infect the adjacent esophagus and ventriculus. The nematodes attach by their anterior end to the mucosal epithelial cells initially causing ulceration at the site of attachment. In most avian species these worms cause only a mild nodular reaction in the mucosa and a small amount of inflammation. However in some species (American wood cock, ruffed grouse, blue grouse) D. nasuta acts as a primary pathogen.(5,7) When present in large numbers (10 or more), the infection causes severe hyperplasia of the proventricular glands. Associated with the glandular proliferation is an increase in mucus production, as well as excessive sloughing of mucosal epithelial cells. As a result, the lumen of the proventriculus becomes distended by a thick, white, coagulum of mucus and sloughed cells which creates a functional obstruction of the proventriculus and secondary starvation.(5,7)

Diagnosis in this case was made based on the characteristic proventricular lesion, egg and adult worm identification. As stated previously, the significance of this parasite is variable. In most birds this nematode is an incidental finding. However in some species, particularly the ruffed grouse and blue grouse, these organisms are believed to be a significant cause of mortality and decline in wild populations. While not typically considered a primary pathogen of free ranging bobwhites, significant mortality has been seen in cage-reared animals.(5,7,8)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Proventriculus: Proventriculitis, proliferative and heterophilic, diffuse, marked with glandular ectasia and adult spirurids

2. Serosa, adipose tissue: Atrophy, diffuse, moderate

Conference Comment:

In a retrospective study done by Drs. Raymond, Miller, and Garner it was found that in two cases infection with D. nasuta, also known as adenomatous proliferative proventriculitis (APP), the lesions progressed to proventricular adenocarcinoma.(9) In humans and domestic animals, several parasites have been associated with subsequent neoplasia. A brief, non-comprehensive list is included.

| Spirocerca lupi | Esophageal sarcoma in dogs |

| Opisthorchid flukes | Cholangiocarcinoma in cats and man |

| Cysticercus fasciolaris | Hepatic sarcoma in rats |

| Clonorchis sinensis | Cholangiocarcinoma in cats and man |

| Schistosoma haematobium | Carcinoma in bladder of humans |

| Trichosomoides crassicauda | Papillomas in urothelium in rats |

References:

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK: The alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 40-41, 256. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

3. Epstein JI: The lower urinary tract and male genital system. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. V. Kumar, A. K. Abbas, N. Fausto, 7th ed., pp. 1032, Elsiever, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, 2005

4. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL: In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, 2nd ed., pp. 30-34. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC 1998

5. Goble FC, Kutz HL: The genus dispharynx (Nematoda: Acuariidae) in galliform and passeriform birds. Journal of Parasitology 31:323-331, 1945

6. Percy DH, Barthold SW: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 3rd ed., pp.160. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa, 2007

7. Proventricular or Stomach Worm. http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,1607,7-153-10370_12150_12220-27255--,00.htm

8. Purvis JR, Peterson MJ, Lichtenfels JR, Silvy NJ: Northern bobwhites as disease indicators for the endangered Attwaters prairie chicken. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 34:348-354

9. Raymond JT, Miller C, Garner MM: Adenomatous proliferative proventriculitis (APP) in birds. Journal Proceedings, AAZV Conference, Milwaukee, WI, 2002

10. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp.363. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

11. Urquhart GM, Armour J, Duncan JL, Dunn AM, Jennings FW: Veterinary Parasitology, pp.82 83, Churchill Livingstone Inc., 1994