Signalment:

5-year-old, female, spayed, domestic shorthair cat (

Felis catus).The cat had neurologic signs that ended in torticollis and vocalization.

Gross Description:

There were no gross lesions in the viscera, brain, or spinal cord.

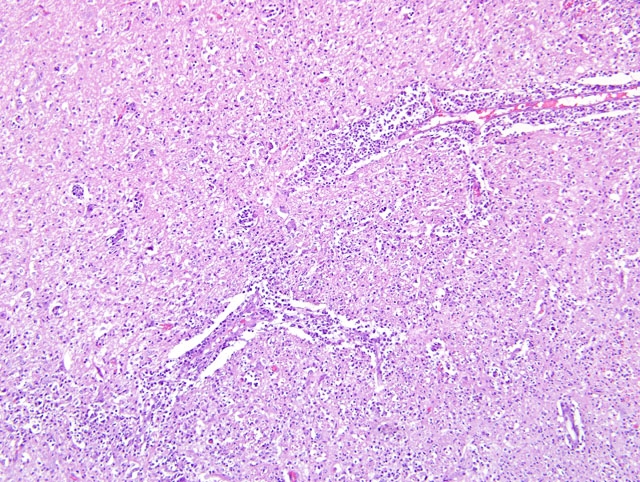

Histopathologic Description:

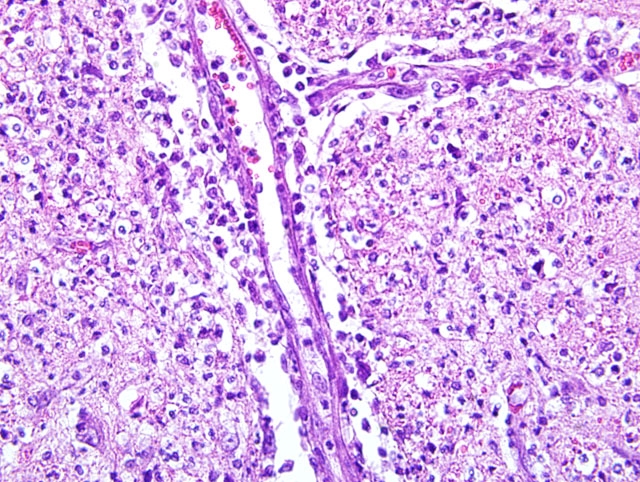

A diffuse and severe influx of neutrophils was present throughout the brainstem.

Only slight lymphocytic perivascular cuffing with a few neutrophils was in the adjacent cerebellar white matter and

focally in the posterior cerebral white matter and midbrain. Mostly neutrophils with some lymphocytes and

histiocytes surrounded the vessels and infiltrated and thickened their walls with mostly neutrophils within the brain

parenchyma. Occasionally, the cytoplasm of degenerating neurons was filled with neutrophils (neurophagia). The

trigeminal ganglia (not on slide) were collected from the refrigerated body about three days later, and one also had

mild lymphocytic inflammation, a few neutrophils, and multiple colonies of short gram-positive bacilli, compatible

with

Listeria (cold enrichment). Inflammation was absent in the meninges except for occasional perivascular

inflammation in the subarachnoid spaces of the brainstem.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Diffuse, suppurative brainstem encephalitis.

Lab Results:

Rabies fluorescent antibody test: Negative.Â

West Nile Virus PCR: Negative.Â

Bacterial culture: Brainstem, anterior cervical spinal cord = 2+

Listeria monocytogenes; liver = no growth.

Condition:

Listeria monocytogenes

Contributor Comment:

This is neurologic listeriosis as would be expected in a ruminant. In ruminants, infection

is generally associated with feeding silage. The bacteria can live if the silage pH is above 5.5. In Arkansas, we see

sporadic cases in cattle and goats on pasture and eating round bales of hay that may be spoiling on the ground side.

Infection gains entry to a mouth lesion and the bacteria travel up axons of the trigeminal nerve to the trigeminal

ganglion and brainstem. The characteristic lesion is brainstem microabscesses or glial nodules that eventually fill

with neutrophils, and lymphocytic perivascular cuffing and local brain parenchymal edema and rarefaction. Mild

meningitis of the cerebellum and anterior spinal cord is common. Encephalitic cases are rare in dogs(2) and no

report was found of neurologic listeriosis in a cat and few septicemic cases.(3) Listeriosis typically has one of three

separate entities: encephalitis, septicemia, or metritis/abortion.(3) The lesions in this cat are much more suppurative

than we usually see in ruminants.

JPC Diagnosis:

Brainstem and cerebellum: Encephalitis, suppurative, multifocal to coalescing, marked.

Conference Comment:

In addition to the lesions described by the contributor, conference participants noted

reactive astrocytosis and rare foci of neutrophilic inflammation within the cerebellar white matter on some slides.

Several conference participants considered feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) in the differential diagnosis. However,

several histologic findings argue against a diagnosis of FIP: 1) inflammation elicited in FIP is classically

pyogranulomatous, whereas the inflammation in this case is predominantly neutrophilic; 2) neutrophils in the

pyogranulomatous inflammation of FIP are classically nondegenerate, whereas the neutrophils in this case are

mostly degenerate; and 3) inflammation in FIP is generally centered on blood vessels, ventricles, and choroid plexus,

whereas in this case, foci of inflammation are scattered randomly throughout the neuropil of the brainstem. The

tissue Gram stain demonstrates numerous gram-positive short bacilli, and in congruence with the reported bacterial

culture results, solidifies the diagnosis of encephalitic listeriosis.

In humans and animals,

L. monocytogenes is credited with producing three distinct syndromes, each of which is

thought to develop by a unique pathogenesis. The first, as demonstrated by this case, is encephalitis, which occurs

almost exclusively in ruminants and is associated with feeding incompletely fermented silage where the bacterium

readily multiplies, as described by the contributor. Interestingly, although

L. monocytogenes has been shown

experimentally to breach the blood-brain barrier, the distribution of lesions in naturally-occurring cases of listerial

encephalitis suggests direct invasion through the oral mucosa, ascension through the trigeminal nerves, and

centripetal travel via axons to the brain, rather than hematogenous infection. Preferentially affected are the medulla

and pons, with less severe infection in the thalamus and cervical spinal cord. Classically, clinical signs consist of

depression, head-pressing, and circling, often with unilateral paralysis of the seventh cranial nerve and resultant

facial drooping and/or unilateral purulent endophthalmitis, which may be confused with malignant catarrhal fever.

(2)

The second syndrome is abortion, which is thought to result from hematogenous infection of the pregnant uterus

following an asymptomatic bacteremic phase. In cattle and sheep, abortions occur in the third trimester of

pregnancy, often without clinical illness in the dam, followed typically by retention of the placenta. Infection in the

early part of the third trimester results in expulsion of an autolyzed fetus. Late third trimester infections produce the

third listeriosis syndrome, septicemia, characterized by miliary yellow foci of necrosis and bacteria that are grossly

evident in the liver, and microscopically also found in the lung, heart, kidney, spleen, and brain. Both the

cotylendonary and intercotyledonary regions of the placenta are affected by a robust necrotizing placentitis.

Interestingly, it is uncommon for the encephalitis and abortion syndromes to occur together in a herd or flock.(4)

In addition to the remarkable ability of this ubiquitous saprophyte to survive and grow in the environment,

L.

monocytogenes persists indefinitely in macrophages, thereby escaping the humoral immune system. The bacterium

induces phagocytosis via a cell surface protein called internalin; inside the cell it escapes phagosome-mediated

killing via such virulence factors as listeriolysin O and phospholipases. Then, in a most impressive display of

stealth,

L. monocytogenes manipulates host cell contractile actin to facilitate movement from cell to cell without

exposure to antibodies.(1,2)

References:

1. Greene CE: Listeriosis.Â

In: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, ed. Greene CE, 3rd ed., pp. 311-312.

Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2006

2. Maxie MG, Youssef S: Nervous system.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed.

Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 405-408. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

3. Rogers JJ: Listeriosis in a young cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc

168:1025, 1976

4. Schlafer DH, Miller RB: Female genital system.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic

Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, pp. 492-493. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2007