Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 8

23 October 2019

Dr. Dalen Agnew, DVM, PhD, DACVP

|Associate Professor

Pathobiology and Diagnostic Investigation

Michigan State University

College of Veterinary Medicine

East Lansing, Michigan

CASE I: D19-007212 (JPC 4135866).

Signalment: 21-month-old female Welsh Corgi mixed breed dog

History: Following spay procedure; a section of uterus was submitted for biopsy evaluation.

Gross Pathology: NA

Laboratory results: NA

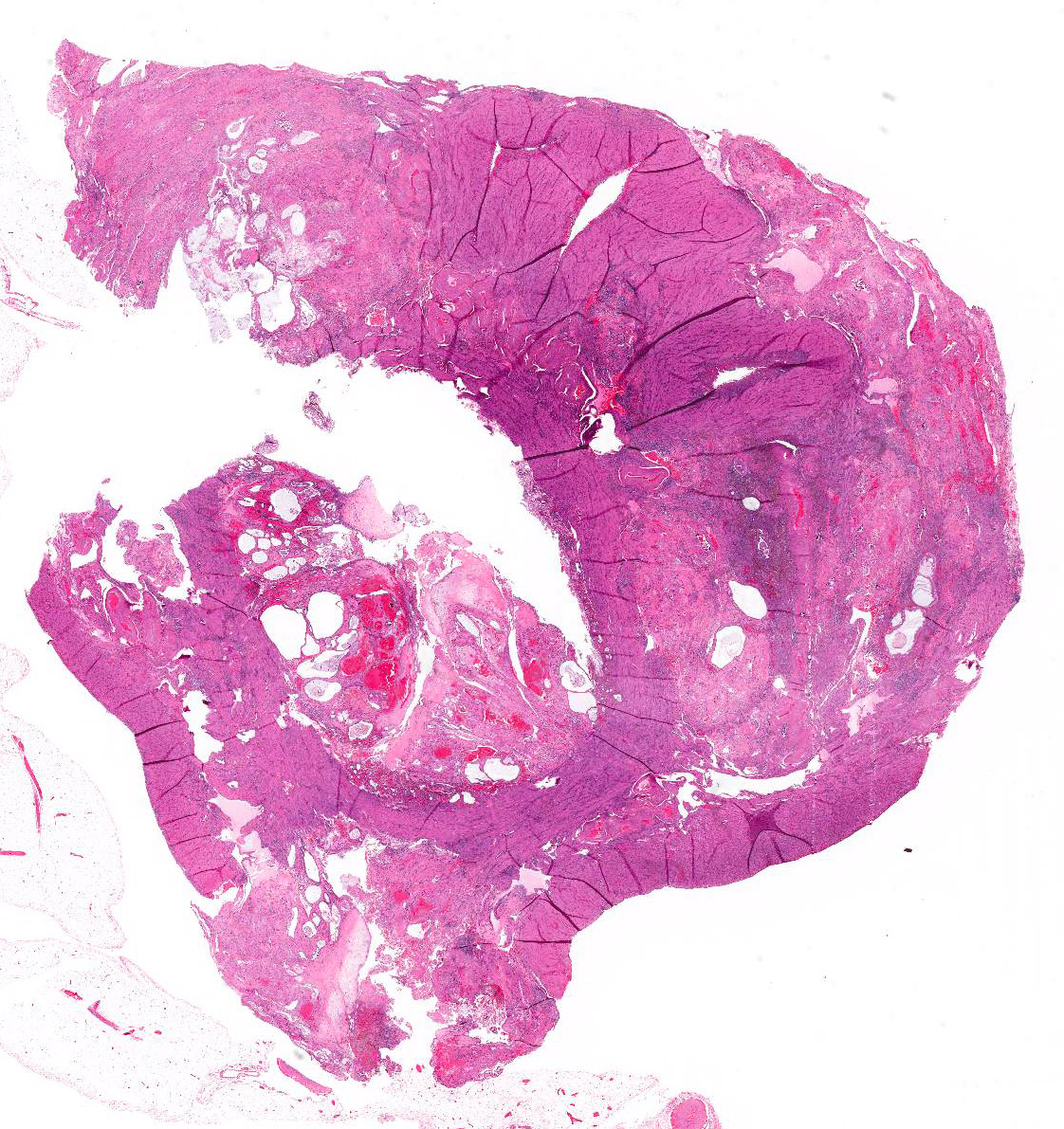

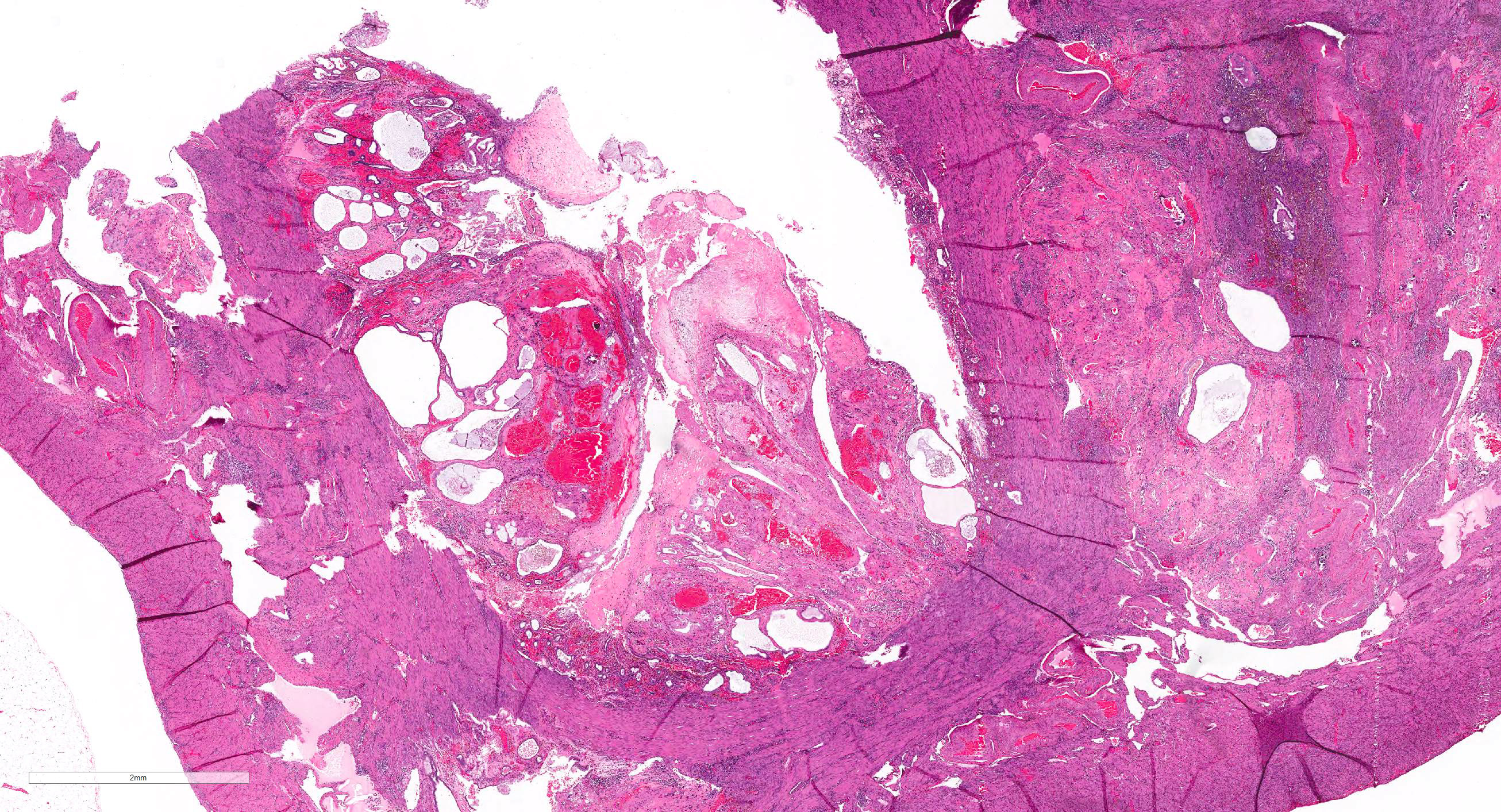

Microscopic Description:

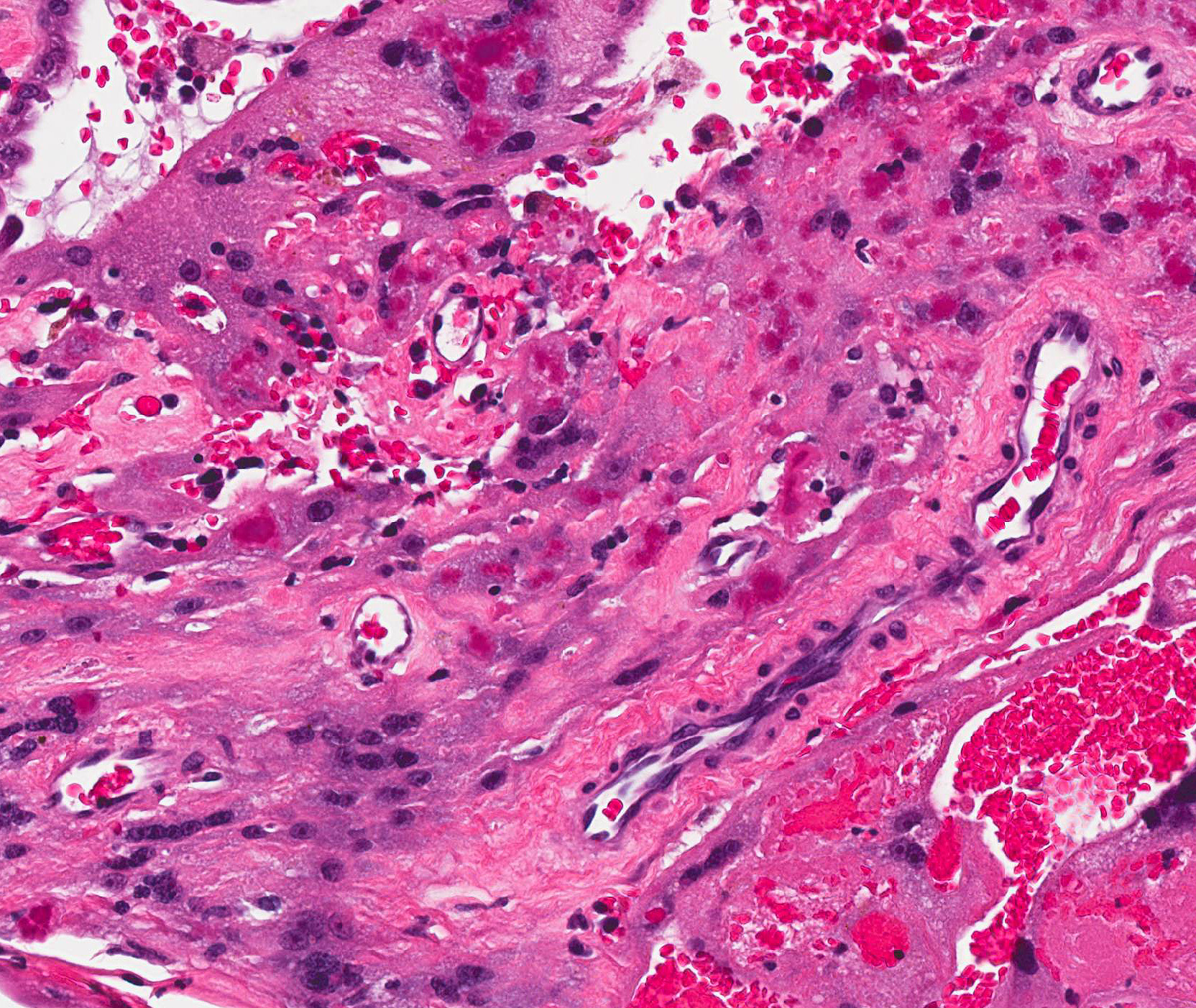

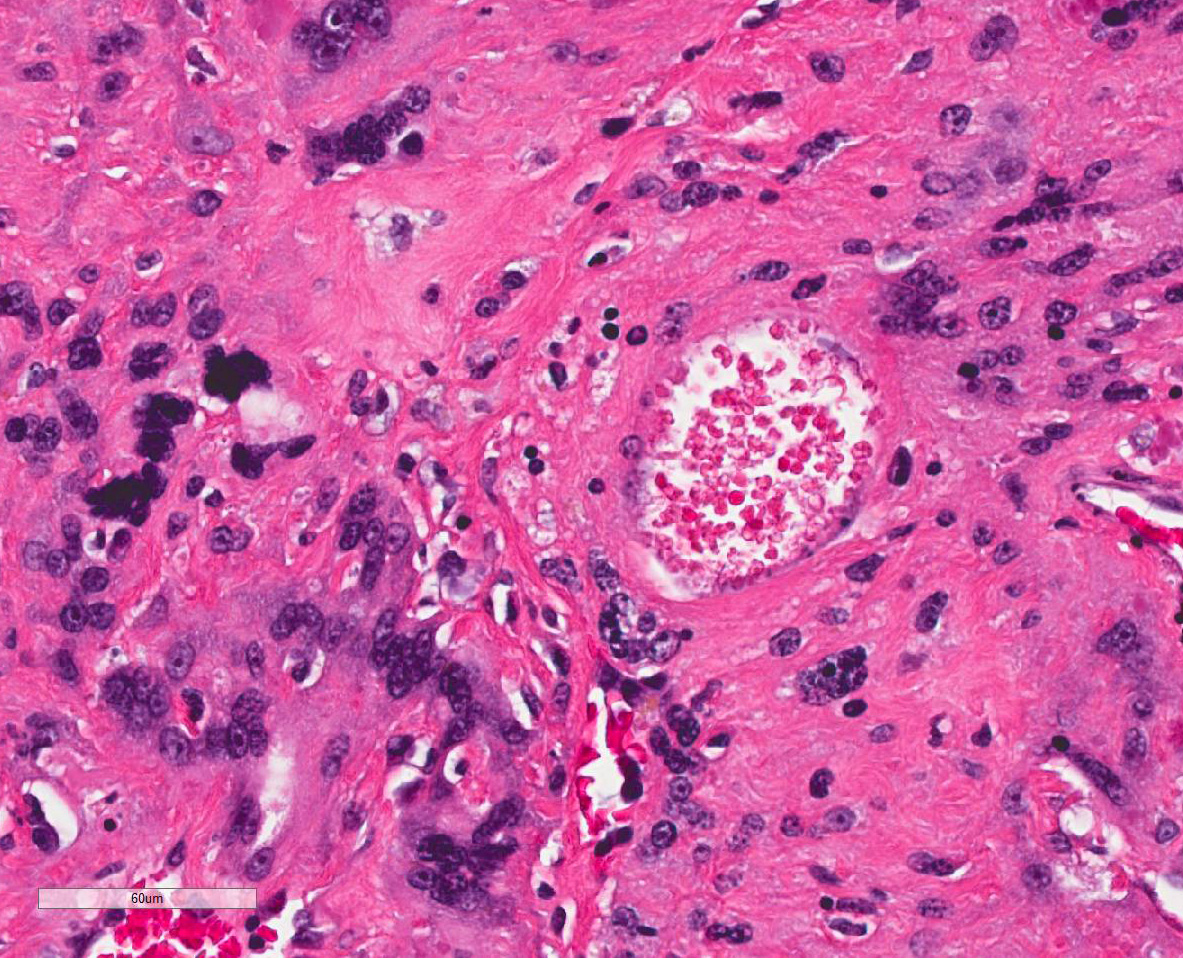

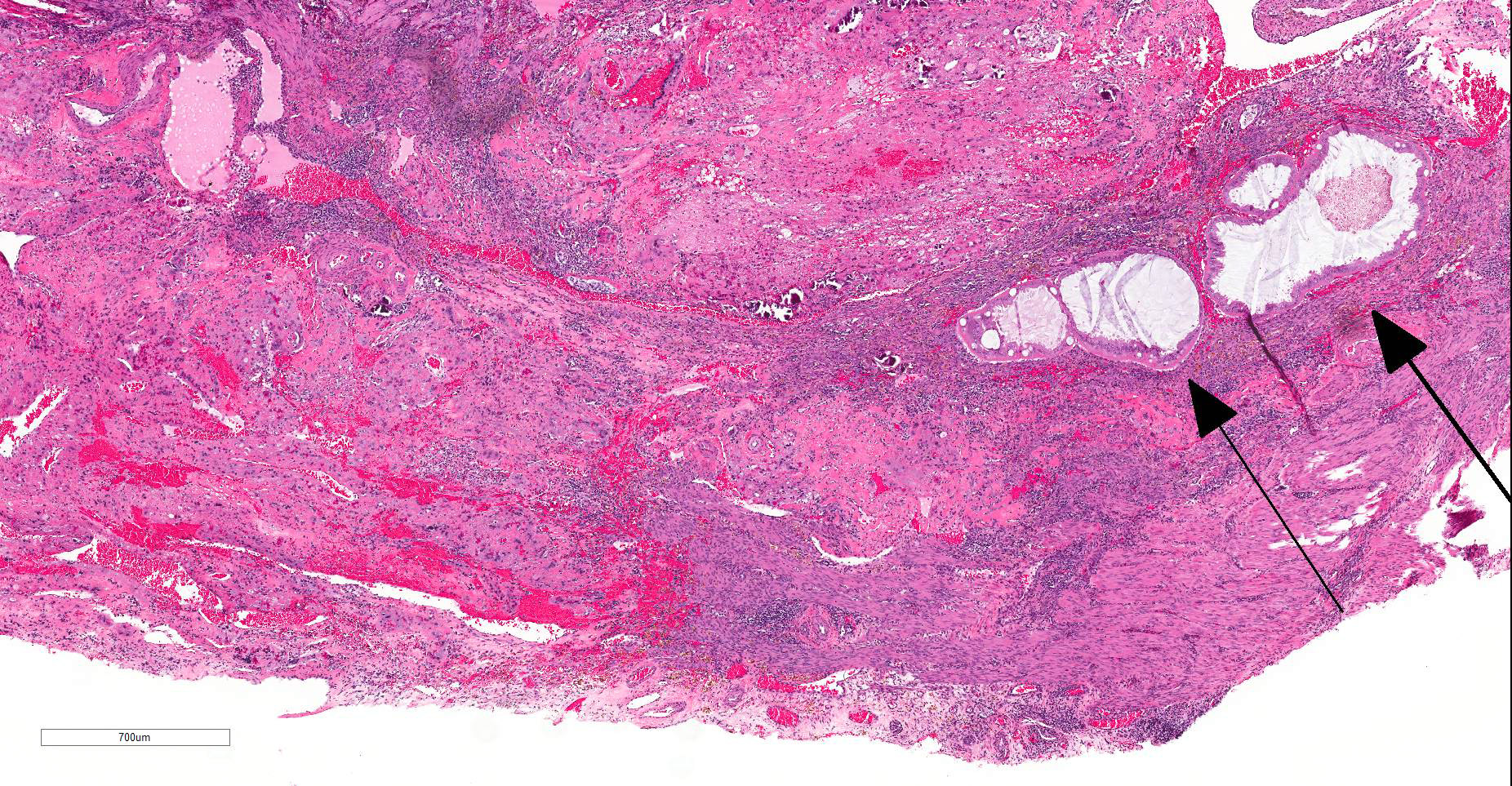

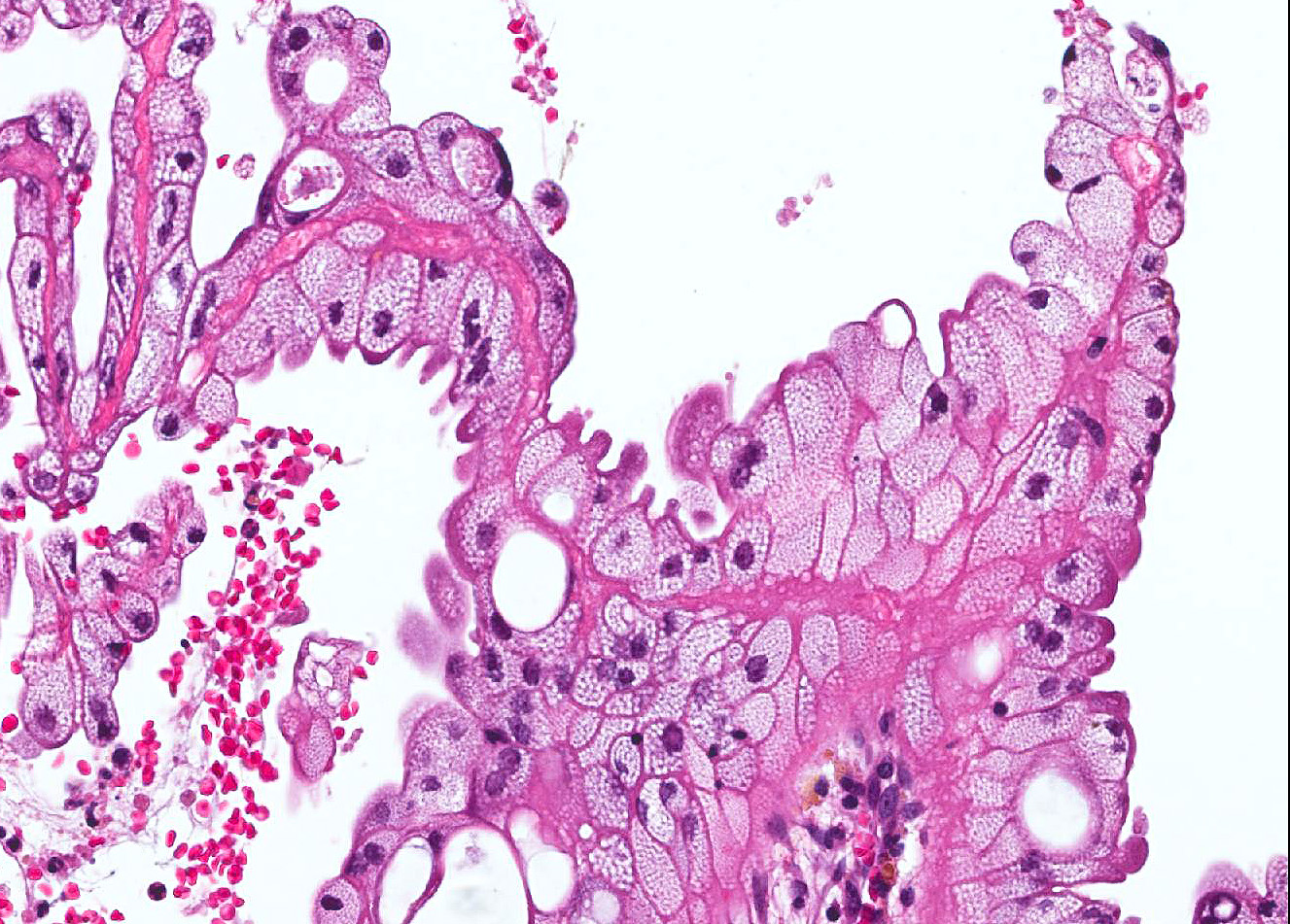

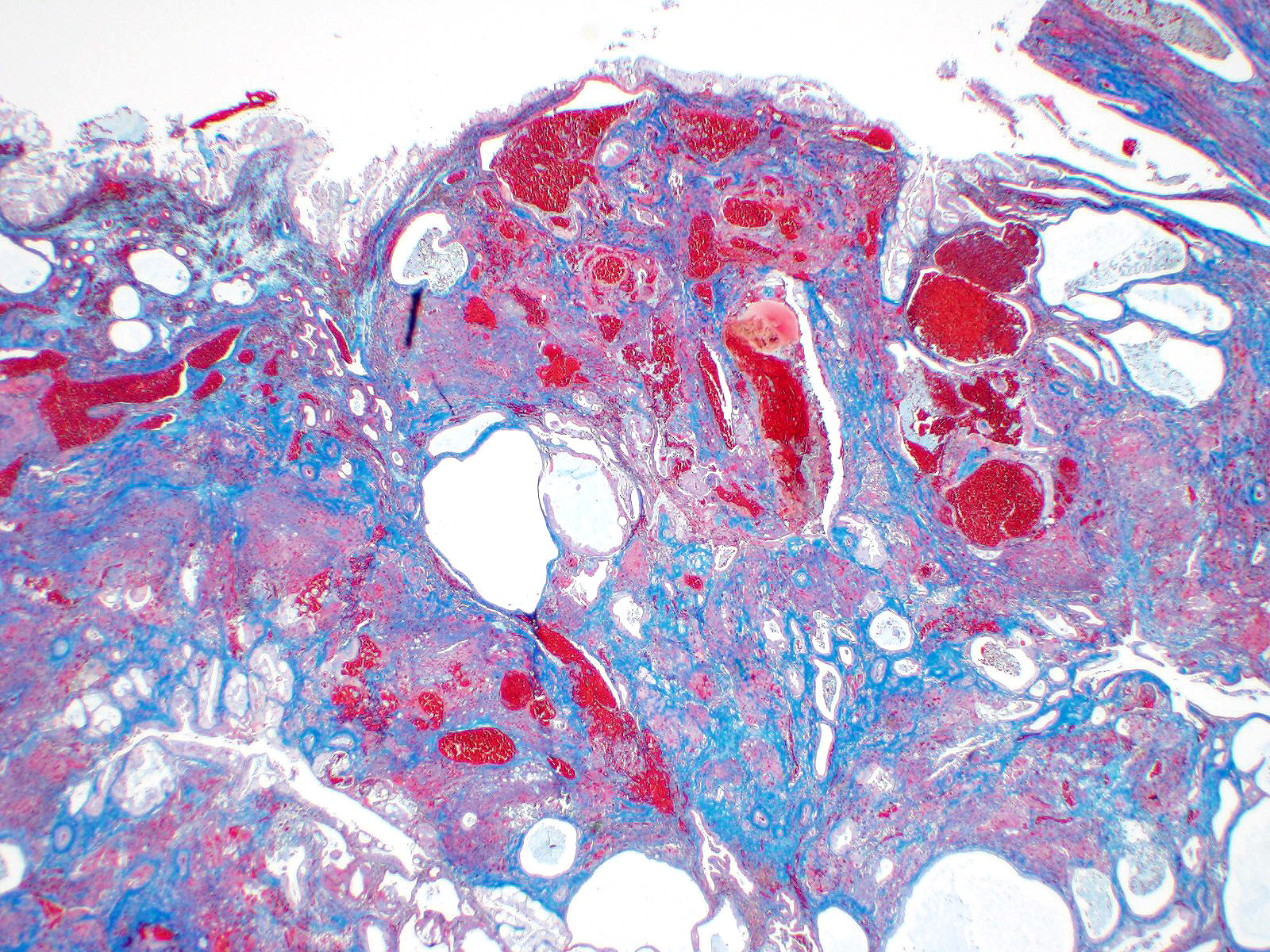

Uterus: Diffusely and markedly expanding the endometrium, extending into the luminal space, and infiltrating into the myometrium are markedly ectatic endometrial glands which are admixed and/or surrounded by a coagulum of degenerate neutrophils, eosinophilic karyorrhectic and cellular debris, congested blood vessels, multifocal hemorrhage, hemosiderin, fibrin, and sloughed epithelial cells. These sloughed cells are similar to those lining remaining intact endometrium and are tall columnar epithelial cells with contain highly vacuolated cytoplasm. The myometrium is multifocally infiltrated by large numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages. Multifocally, within the endometrial coagulum and the underlying myometrium are scattered aggregates of irregularly shaped syncytial trophoblast cells which contain up to 6-10 nuclei with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and multifocal mild mineralization. There is focal rupture of the serosa with transmural proliferation/invasion of endometrial glands, hemorrhage, fibrin, and yellow pigment (hematoidin).

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Uterus: Necrosis, hemorrhage, and mineralization with syncytial trophoblast retention, endometrial hyperplasia, and serosal rupture

Condition: Subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS)

Contributor Comment: Clinical presentation of subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS) typically consists of blood-tinged vaginal discharge that extends past the normally expected 7-10 days post-whelping1, sometimes lasting for months. The condition occurs most commonly in young dogs and the cause is unknown. Prolonged bleeding and extensive loss of blood can lead to anemia and occasionally death. Affected dogs are also prone to ascending infections.

Normal uterine involution in dogs takes 12-15 weeks3. In dogs with SIPS gross lesions consist of some or all of the placental attachment areas (ellipsoidal enlargements) being thickened, rough, grey to brown and hemorrhagic with the inter-placental sites appearing normal.

Microscopically, SIPS are characterized by a luminal coagulum of abundant necrotic cellular debris, hemorrhage, and within the deeper layers of endometrium, syncytial trophoblasts or decidual cells that have a vesiculate nucleus and highly vacuolated cytoplasm due to progesterone stimulation. The retained trophoblastic cells fail to degenerate and subsequently invade into the deeper glandular layer and myometrium. 2 These trophoblastic cells also inhibit normal thrombus formation leading to prolonged bleeding. 4 Mineralization and infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages often occur in these areas of necrosis. The syncytial trophoblasts or decidual cells may invade deeper layers including the myometrium and also may cause serosal rupture (as seen in this submitted case) leading to escape of the contents into the peritoneal cavity causing fatal peritonitis 1. Spontaneous recovery generally occurs in healthy dogs and in prolonged cases ovariohysterectomy must be performed for resolution of the condition4,5.

Other differentials for hemorrhagic vaginal discharge include endometritis, neoplasia, coagulopathies, brucellosis and other bacterial infections.

Contributing Institution:

Kansas State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

JPC Diagnosis: Uterus,

Endometritis, chronic-active and necrohemorrhagic , diffuse, severe, with

numerous myometrial trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, adenomyosis, and

progesterone effects.

JPC Comment: In domestic species, subinvolution of

placental sites is a condition unique to the bitch. In humans, subinvolution

of the placental site (also known as non-involution of the placental site or

subinvolution of the uteroplacental arteries), is an uncommon cause of

postpartum bleeding in older multiparous women. Unlike the dog, in humans it

is most often diagnosed within several weeks postpartum, although cases have

been diagnosed as long as 6 years after the most recent parturition.6

In humans, this condition is different from the bitch, in that hemorrhage is

usually the result of failure occlusion of the placental vessels.

During mid- to late gestation in humans, endovascular trophoblasts actually

replace the endothelial lining of the uteroplacental arteries, expressing

endothelial-type markers and angiogenic factors resulting in significant

remodeling of the arterial bed to create low-resistance high-flow arteries to

supply the needs of the developing fetus.6 Within days after birth,

these trophoblasts disappear, resulting in endarteritis, thrombosis, and

occlusive mural fibrosis of these vessels, which coincides with loss of the

decidua and endomyometrium in the remainder of the uterus, and limits blood

loss during this process. While the pathogenesis of this process has not yet

been fully elucidated, it is likely that the lack of involution of placental

vessels results from abnormal immunologic recognition, as the normal deposition

of immunoglobulin (IgG, IgM, and IgG) and complement proteins (C1q, C3d, C4)

seen in normally involuted arteries is not seen in those associated with

subinvolution. Additionally, remnant endovascular trophoblasts in

non-involuting placental vessels express high levels of the anti-apototic protein

Bcl-2.6

References:

1 In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6 ed.; 2016: 358-464.

2 Al-Bassam MA, Thomson RG, O'Donnell L: Involution Abnormalities in the Postpartum Uterus of the Bitch. Veterinary Pathology 1981:18(2):208-218.

3 Al-Bassam MA, Thomson RG, O'Donnell L: Normal postpartum involution of the uterus in the dog. Canadian journal of comparative medicine : Revue canadienne de medecine comparee 1981:45(3):217-232.

4 Johnston SD, Root Kustritz MV, Olson PS: Canine and feline theriogenology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2001.

5 Sontas HB, Stelletta C, Milani C, Mollo A, Romagnoli S: Full recovery of subinvolution of placental sites in an American Staffordshire terrier bitch. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2011:52(1):42-45.

6. Wachter DL, Thiel F, Agaimy A. Subinvolution of the placental site six years after last delivery. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2011; 581-582.

7. Weydert JA, Benda JA: Subinvolution of the Placental Site as an Anatomic Cause of Postpartum Uterine Bleeding: A Review. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2006:130(10):1538-1542.