WSC 22-23

Conf 10

Case 4:

Signalment:

A 3-year-old female (intact) Mastiff dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

The dog presented with a two-day history of lethargy, inappetence, pyrexia, coughing and a brown/red vaginal discharge. She had been previously diagnosed with a steroid-responsive cough (one year prior to current presentation).

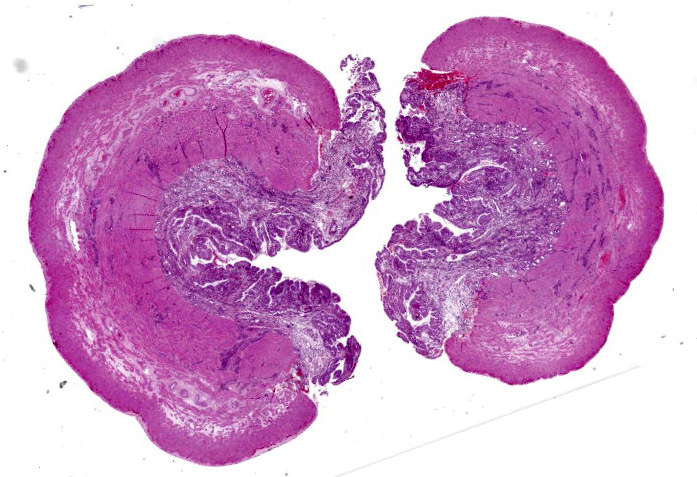

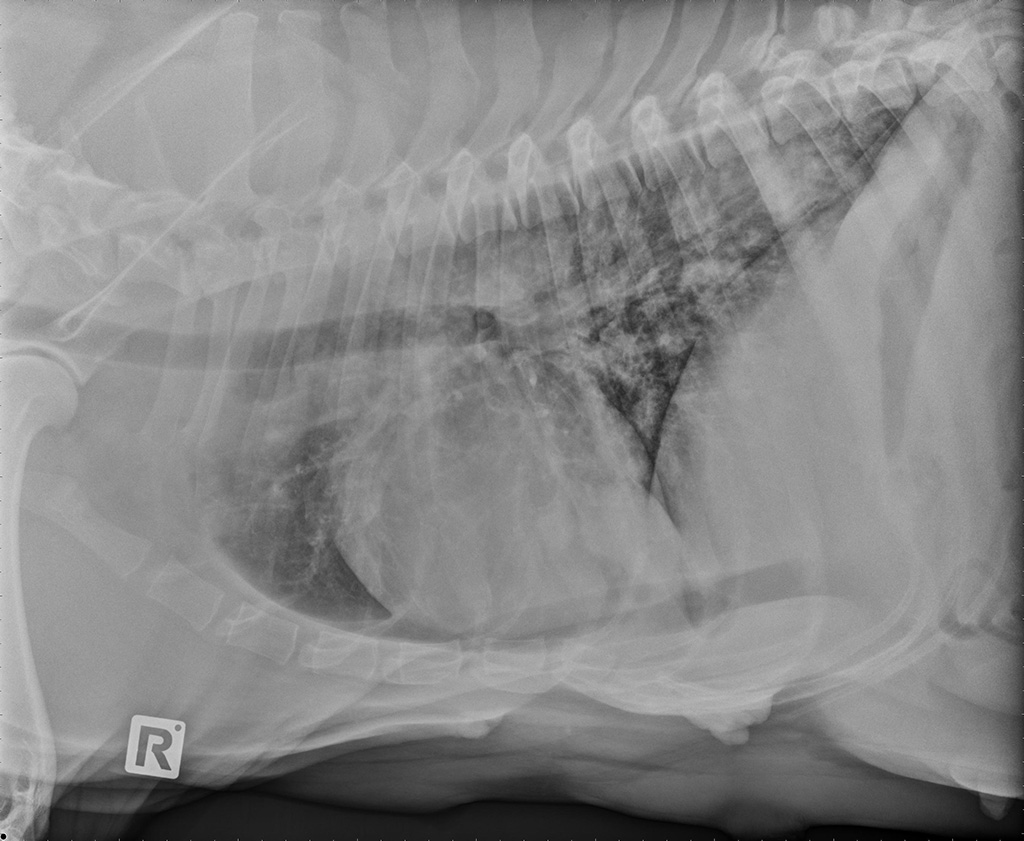

On clinical presentation, the dog was dehydrated, pyrexic and had a thick vaginal discharge. Digital examination of the reproductive tract revealed an open cervix. Abdominal radiographs and ultrasonography showed a fetus with no heartbeat in the uterus. Abortion and pyometra were diagnosed, and an ovariohysterectomy was performed. To further investigate the respiratory disease, thoracic radiographs and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were performed. Radiographs revealed a bronchointerstitial pattern with bronchiectasis (Fig. 1) and BAL showed a differential count of 40-45% eosinophils, 40-45% neutrophils, 10-15% macrophages, and rare lymphocytes in a lightly mucinous background (Fig. 2).

Following surgery, the dog presented twice (11 days and 2 months post-surgery) with a cough and labored breathing. On both occasions the dog responded to corticosteroid treatment. Thoracic radiographs taken at two months post-surgery revealed a bronchointerstitial pattern and a 3 cm opaque mass in the caudal lung lobe. Based on clinical and clinico-pathological findings a diagnosis of canine eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EBP) was proposed. Unfortunately, there was no repeat bloodwork and the dog was lost to follow up.

Gross Pathology:

The uterus, the placenta and the aborted fetus were submitted for microscopic examination. The uterine mucosa was pale tan to green, irregular and thickened.

Laboratory Results:

CBC showed a marked eosinophilia (11.86 x 109/L), neutrophilia (14.35 x 109/L), basophilia (1.01 x 109/L), and a mild regenerative anemia (HCT 37%). Biochemistry showed a mild increase in creatinine 166 μmol/L (range: 44-159 μmol/L). A Baermann test for lungworm larvae was negative.

Microscopic Description:

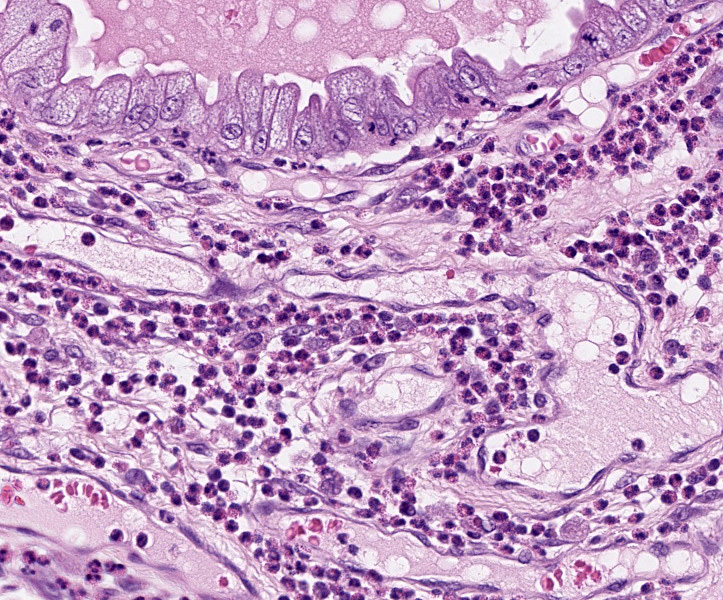

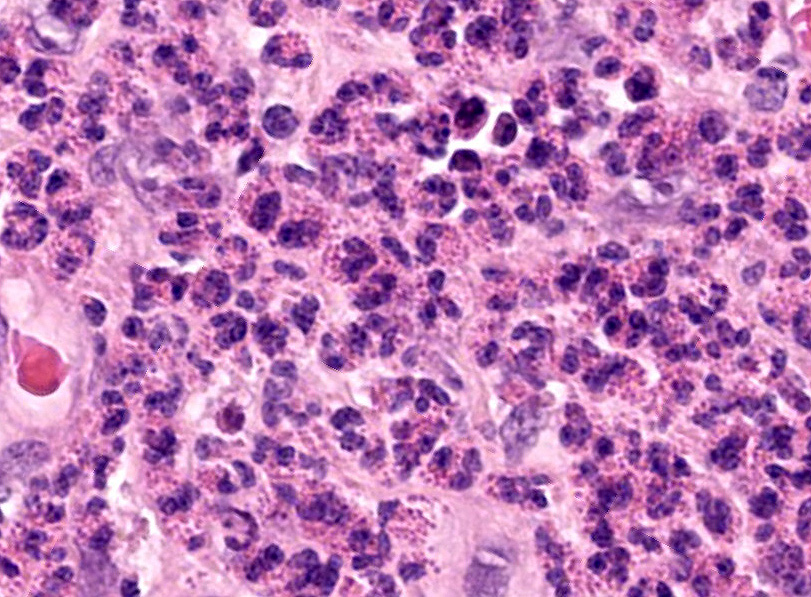

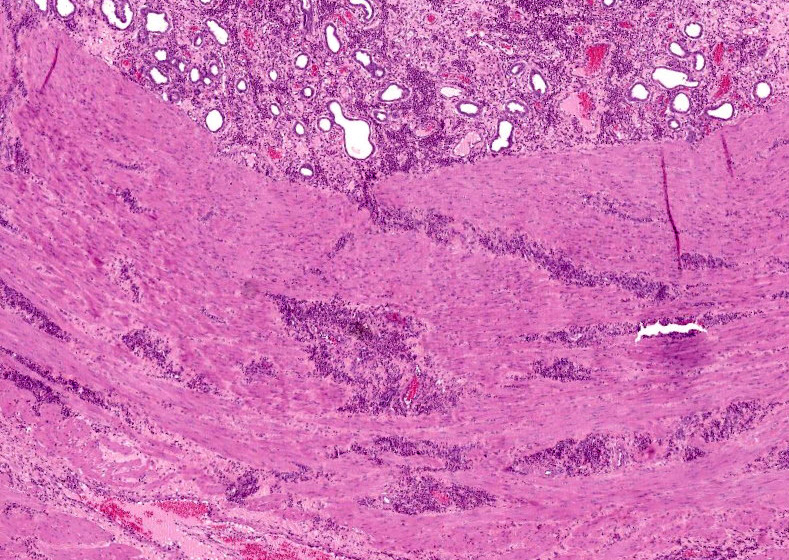

Uterus: The endometrium is circumferentially expanded by the presence of large numbers of eosinophils and lesser numbers of foamy macrophages that diffusely infiltrate the interstitium and separate endometrial glands. Multifocally, eosinophils and rare neutrophils are seen migrating through the endometrial epithelial lining. The endometrial glands are mildly dilated, occasionally tortuous, and mostly lined by cuboidal epithelium. Rare granulocytes are present in the lumen of the glands. In the surface epithelium, cells are arranged in a single layer or are pseudostratified. Endometrial epithelial cells vary from low cuboidal, to tall columnar with eosinophilic foamy cytoplasm and vesiculate nuclei (progestational epithelium). Endometrial blood vessels are moderately congested and lymphatics are ectatic. There are multifocal areas where the endometrial stroma is distended with numerous clear spaces separating blood vessels and endometrial glands (edema). In the lumen of the uterus, there are scattered, multifocal aggregates of erythrocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils admixed with cellular debris. There is moderate to marked edema in the stratum vasculare causing separation of the inner and outer layers of the myometrium with multifocal, dense aggregates of eosinophils infiltrating and separating interconnecting bundles of smooth muscle and surrounding vessels.

Special stains: Luna and Congo red stains demonstrated bright orange to red granules in the cytoplasm of the numerous eosinophils present throughout the endometrium and myometrium.

Tissue autolysis prevented optimal examination of the fetus and the placenta.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Uterus: Eosinophilic endometritis and myometritis.

Contributor’s Comment:

This case is unique in presenting with eosinophilic endometritis and myometritis, eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EBP), and peripheral blood eosinophilia. It is unclear whether the eosinophilic endometritis and myometritis, and the EBP are separate entities or whether these conditions may be part of the multisystemic disorder termed hypereosinophilic syndrome. An eosinophilic leukemia, characteristically presenting with a peripheral eosinophilia count greater than 25 to 30 eosinophils × 109/L,16 was excluded based on a peripheral count of 11.86 x 109/L in this patient.

Eosinophilic endometritis and myometritis, representing an abundant eosinophilic infiltration of the endometrium and myometrium respectively, are occasionally reported in dogs. In a recent study, 7.3% of endometrial biopsies in subfertile dogs were classified with eosinophilic endometritis.12 Despite the surprisingly common incidence of this condition, the pathogenesis and clinical significance remains poorly understood. A significant relationship between eosinophilic endometritis and fetal loss has been established. However, it is unclear if eosinophilic infiltrates result in fetal loss, or if eosinophils infiltrate secondarily to tissue responses associated with placental maturation and late pregnancy.12 It has been previously reported that high numbers of eosinophils may be present in the uterus of healthy post-partum doges, whereas low numbers of eosinophils may be seen during pro-estrus, estrus, diestrus, early pregnancy and early to mid-anestrus post-partum.27

Eosinophilic endometritis has been reported in several other species including ferrets,11 horses,23 donkeys,24 and elk.4 In ferrets, eosinophilic endometritis was attributed to fetal death resulting from suspected “single kitten syndrome.”11 A similar entity termed “single pup syndrome” has been reported in dogs, where a single-fetus pregnancy results in failure of parturition.19 It is believed that the single puppy produces insufficient cortisol and ACTH to initiate parturition, and if the birth process is not initiated, the placental supply of oxygen and nutrients diminishes leading to fetal death and mummification or maceration in utero. A diagnosis of “single pup syndrome” could be potentially considered in the present case. In horses, a causal association between pneumovagina and pneumouterus leading to eosinophilic endometritis has been suggested.23

The failure of a single pup to initiate the onset of parturition on or around the expected date has been postulated to be due to the concentration of cortisol secreted by one pup being insufficient to adequately initiate luteolysis via prostaglandin release.

Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy is a disease characterized by eosinophilic infiltration into the bronchi, terminal bronchioles, alveoli and blood vessels. Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes appear overrepresented. In some cases, blood peripheral eosinophilias are reported concurrently.9 Affected dogs usually present with a corticosteroid responsive cough, similar to the patient from the case described here. Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy is typically diagnosed by cytological examination of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or histologic examination of the bronchial mucosa, combined with radiographic and bronchoscopic findings and exclusion of known causes of eosinophilic infiltration into the airways. In dogs, the most common causes of eosinophilic pneumonitis include heartworm disease caused by Dirofilaria immitis and migration of Angiostrongylus vasorum larvae through the pulmonary parenchyma.6,17Dirofilaria immitis is a reportable disease in New Zealand and there are no reports of canine infection with A. vasorum, and thus infection with these parasites was considered unlikely in the present case. Less commonly, Oslerus osleri, Filaroides hirthi, Crenosoma vulpis,Paragonimus kellicotti and neoplasia (lymphoma and mast cell tumors) have been implicated with pulmonary eosinophilic infiltrates in dogs.7,18 Other possible causes have been described in the human literature (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, medications, mycobacteria or fungi) and could potentially cause this clinical syndrome in dogs, but no reported cases were found in the literature. While the etiology of EPB remains unclear, hypersensitivity to aeroallergens is suspected, however most cases are still considered idiopathic.7

Little is known about the cytokines and chemokines involved with EBP. Flow cytometric analysis of BAL samples from dogs with EPB demonstrated an increase of CD4+ T-cells and a decrease of CD8+ T-cells, and resolution of clinical signs with corticosteroid treatment normalized the CD4:CD8 ratio.8 It was proposed that CD4+ T-cells are at least in part responsible for the infiltration of eosinophils, which has also been shown in asthmatic humans21 and rodents.15

Alternatively, the underlying cause of the multi-organ eosinophilic infiltrates in the present case may be due to idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). This is a rare systemic illness of unknown cause and presents as a sustained peripheral eosinophilia (>5×109/L) with multi-organ infiltration causing dysfunction.16 In humans, peripheral eosinophilia must be present for at least 6 months to be considered HES.5 Although the cause of HES is still considered idiopathic, it has been proposed that generalized immune dysregulation may lead to increased maturation and recruitment of eosinophils from the bone marrow that enter the circulation and target tissues and organs. Several cytokines, particularly IL-5 and eotaxin, which prime, activate and enhance eosinophilic migration into tissues, have been implicated with HES.16 In dogs, Rottweilers appear overrepresented,25 and the condition has been reported in cats,26 humans,5 and an owl monkey.13 In horses, multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease is considered the equivalent to HES. Affected horses present with a peripheral eosinophilia of unknown primary origin with multi-organ infiltration.22

In dogs with HES, eosinophilic infiltrates have been reported in several organs including the liver, spleen, lung parenchyma, myocardium, lymph nodes, skeletal muscle and bone marrow.1,14,20,25 Although pulmonary eosinophilic infiltrates are common in dogs with HES, the case presented here could be the first description of uterine infiltrates in an HES dog.

In the human literature, few reports of pregnant women with HES appeared to have minimal complications with no mention of eosinophilic uterine infiltrates. One baby was delivered with a transient hypereosinophilia and there was a single report of a premature twin delivery, however these and all other cases resulted ultimately in the delivery of healthy infants.2,3

In this case, the concurrent EBP, eosinophilic myometritis, endometritis and blood peripheral eosinophilia raise the question whether this case should be considered an unusual presentation of HES. A similar report of two Cavalier King Charles Spaniels presenting with eosinophilic stomatitis, peripheral eosinophilia and eosinophilic disease in other body systems also questioned if these cases were unusual presentations of HES.10 Unfortunately, this case was lost to follow up and a definitive diagnosis could not be established. The persistence and worsening of a corticosteroid responsive cough following ovariohysterectomy, and the presence of similar clinical signs one year prior to presentation, suggests at least EBP. Alternatively, the likelihood of HES with pulmonary and uterine infiltrates is also equally considered.

Contributing Institution:

IVABS

Massey University

Palmerston North, New Zealand

JPC Diagnosis:

- Uterus: Endometritis, eosinophilic, diffuse, severe, with edema.

- Uterus, endometrium: Hyperplasia, diffuse, moderate, with progestational change.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a great overview of eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy, eosinophilic endometritis, and the possible link with hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) in this patient. As the contributor states, HES is a rare and life-threatening disease in dogs and information regarding pathogenesis and treatment is extrapolated from the human literature.

One common sequela in humans with HES is a thromboembolic event.17,21 In HES patients, several proteins, cytokines, and chemokines produced by eosinophils create a hypercoagulable state.17,21 Major basic protein damages endothelial cells, causing endothelial cell and platelet activation, while eosinophil cationic protein activates factor XII (Hageman factor).21 Eosinophils also release both tissue factor and plasminogen activator inhibitor 2 and separately inhibit fibrinolysis.17 The net result is a hypercoagulable state, and in humans this manifests as microvascular thrombi in multiple organs and large thrombi within the heart.17 A case of HES-induced thromboembolism was recently reported in a 3 year old boxer dog. The animal presented with respiratory distress, marked eosinophilia, and a thrombus in the left atrium visible on echocardiography.17 Increased D-dimer levels and tissue-factor-activated thromboelastography confirmed that the dog was hypercoagulable, and the dog was euthanized after it developed acute aortic thromboembolism and paraplegia.17 On necropsy, eosinophils infiltrated the lungs, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes and accounted for 90% of the myeloid cells in the bone marrow.17 This was the first case to be thoroughly documented in a dog; however a similar case was reported in an 11 year old mixed breed dog with HES and a possible intracardiac thrombus on echocardiography.21 This patient was unique in that it responded well to treatment with hydroxyurea and prednisolone, and the thrombus was not apparent 3 months later.21 These case reports illustrate that hypercoagulability may be a consequence of HES in dogs, and thromboembolism may be prevented with rapid treatment and resolution of hypereosinophilia, as has been shown in human medicine.17

In addition to the differentials listed by the contributor, another differential diagnosis for hypereosinophilia is paraneoplastic syndrome. In dogs, cats, horses, and humans, lymphomas can rarely cause hypereosinophilia.20 It is believed that lymphocytes elaborate products like IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF which inhibit eosinophil apoptosis and result in eosinophilia.20

References:

- Aroch I, Perl S & Markovics A. Disseminated eosinophilic disease resembling idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome in a dog. Vet Rec. 2001;149(13):386-389.

- Albrecht AE, Hartmann BW, Kurz C, Cartes F & Husslein PW. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome and pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(5):485-486.

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M & Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33(1):186.

- Bender LC, Schmitt SM, Carlson E, Haufler JB & Beyer Jr DE. Mortality of Rocky Mountain elk in Michigan due to meningeal worm. J Wildl Dis. 2005;41(1):134-140.

- Brigden M L. A practical workup for eosinophilia: you can investigate the most likely causes right in your office. Postgrad Med. 1999;105(3):193-210.

- Calvert CA & Losonsky JM. Pneumonitis associated with occult heartworm disease in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186(10):1097-1098.

- Clercx C & Peeters D. Canine eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2007;37(5):917-935.

- Clercx C, Peeters D, German AJ, et al. An immunologic investigation of canine eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy. J Vet Intern Med. 2002;16(3):229-237.

- Clercx C, Peeters D, Snaps F, et al. Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14(3):282-291.

- German AJ, Holden DJ, Hall EJ & Day MJ. (2002). Eosinophilic diseases in two Cavalier King Charles spaniels. J Small Anim Pract. 2002;43(12):533-538.

- Garrigou A, Huynh M, & Pignon C. Dystocia in a young ferret (Mustela putorius furo) with a possible “single kitten syndrome”. Rev Vét Clin. 2004;49(2):63-66.

- Gifford AT, Scarlett JM, & Schlafer DH. Histopathologic findings in uterine biopsy samples from subfertile doges: 399 cases (1990–2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;244(2):180-186.

- Gozalo AS, Rosenberg HF, Elkins WR, Montoya EJ & Weller RE. Multisystemic eosinophilia resembling hypereosinophilic syndrome in a colony-bred owl monkey (Aotus vociferans). J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2009;48(3):303.

- James FE & Mansfield CS. Clinical remission of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome in a Rottweiler. Aust Vet J. 2009;87(8):330-333.

- Lee JJ, McGarry MP, Farmer SC, et al. Interleukin-5 expression in the lung epithelium of transgenic mice leads to pulmonary changes pathognomonic of asthma. J Exp Med. 1997;185(12):2143-2156.

- Lilliehöök I & Tvedten H. Investigation of hypereosinophilia and potential treatments. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33(6):1359-1378.

- Madden VR, Schoeffler GL. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome resulting in distal aortic thromboembolism in a dog. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2016; 0(00):1-6.

- Martin MWS, Ashton G, Simpson VR, & Neal C. Angiostroneylosis in Cornwall: clinical presentations of eight cases. J Small Anim Pract. 1993;34(1):20-25.

- McLean L. Single pup syndrome in an English Bulldog: failure of luteolysis. Companion Anim. 2012;17(9):17-20.

- McNaught KA, Morris J, Lazzerini K, Millins C, Jose-Lopez R. Spinal extradural T-cell lymphoma with paraneoplastic hypereosinophilia in a dog: clinicopathological features, treatment, and outcome. Clin Case Report. 2018; 6(6):999-1005.

- Perkins MC & Watson ADJ. Successful treatment of hypereosinophilic syndrome in a dog. Aust Vet J. 2001;79(10):686-689.

- Robinson DS, Bentley AM, Hartnell A, Kay AB, & Durham SR. Activated memory T helper cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with atopic asthma: relation to asthma symptoms, lung function, and bronchial responsiveness. Thorax. 1993;48(1):26-32.

- Singh K, Holbrook TC, Gilliam LL, Cruz RJ, Duffy J & Confer AW. Severe pulmonary disease due to multisystemic eosinophilic epitheliotropic disease in a horse. Pathol. 2006;43(2):189-193.

- Slusher, S. H., Freeman, K. P., & Roszel, J. F. Eosinophils in equine uterine cytology and histology specimens. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984;184(6):665-670.

- Sokkar SM, Hamouda MA & El?Rahman SM. Endometritis in she donkeys in Egypt. J Vet Med Series B. 2001;48(7):529-536.

- Sykes JE, Weiss DJ, Buoen LC, Blauvelt MM & Hayden D W. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome in 3 Rottweilers. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15(2):162-166.

- Taboada J. Pulmonary diseases of potential allergic origin. Semin Vet Med Surg (Small Anim). 1991;6(4):278-285.

- Takeuchi Y, Matsuura S, Fujino Y et al. Hypereosinophilic syndrome in two cats. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70(10):1085-1089.

- Watts J, Wright P, Lee C. Endometrial cytology of the normal dog throughout the reproductive cycle. J Small Anim Pract. 1998;39(1):2-9.