Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 12

December 13th, 2017

CASE II: N2015-0602 (JPC 4084210).

Signalment: 1.8 year-old, male, African pygmy hedgehog, Atelerix albiventris, hedgehog.

History: This hedgehog had an approximate 3-month history of progressive depression, weight loss, worsening limb tremors, paresis, and hunched posture. Clinical decline persisted despite supportive care and analgesic therapy (Meloxicam). The animal was euthanized.

Gross Pathology: The hedgehog was in good body and postmortem condition. Mild abrasions were present along the ventral trail. Absent gastric content and mild gall bladder distention suggested recent anorexia. There were no other significant gross findings.

Laboratory results:

None provided.

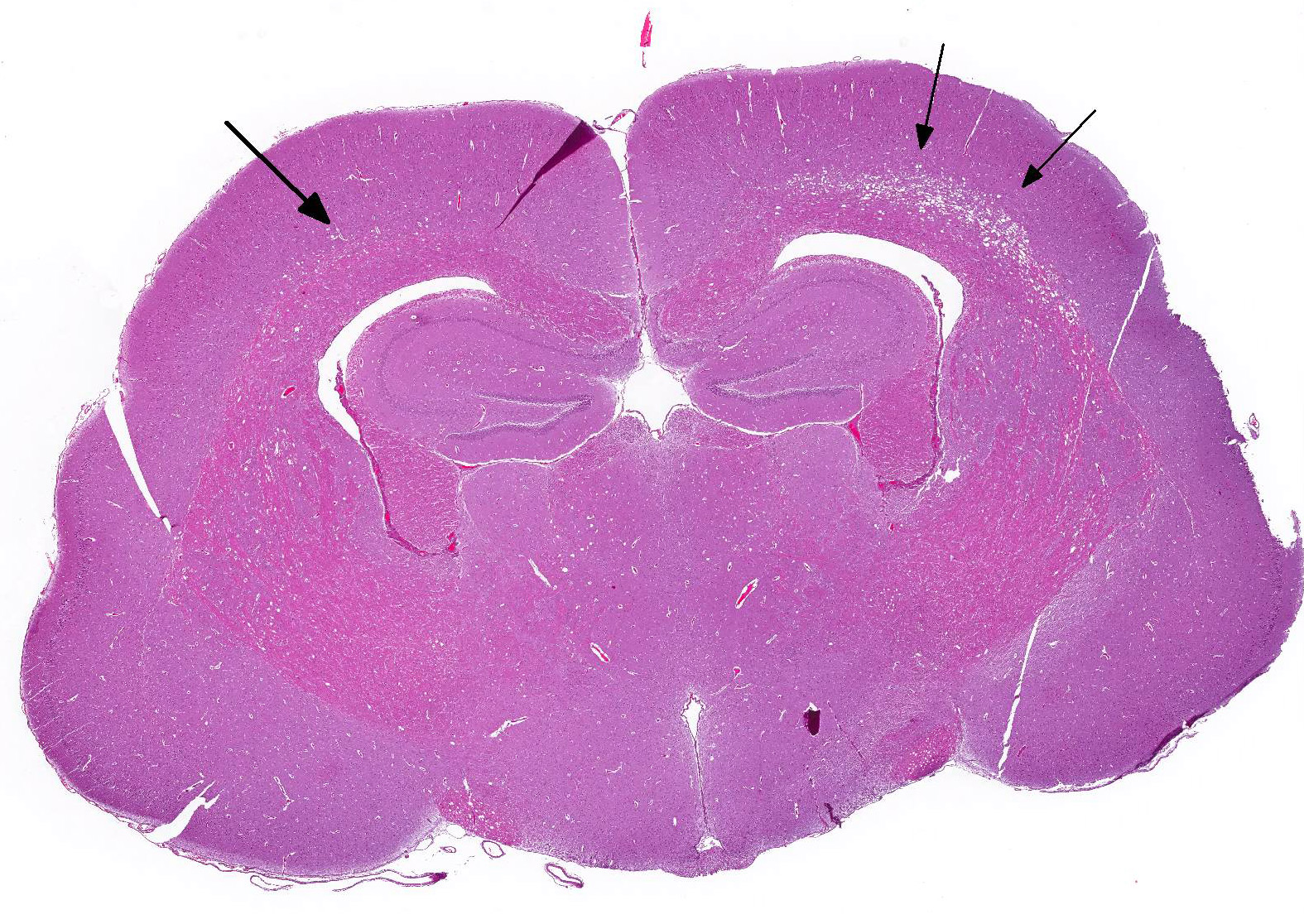

Microscopic Description: Multiple sections along the brain and spinal cord (cerebrum, thalamus, midbrain, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord) were examined. Submitted slides include cerebrum and brainstem.

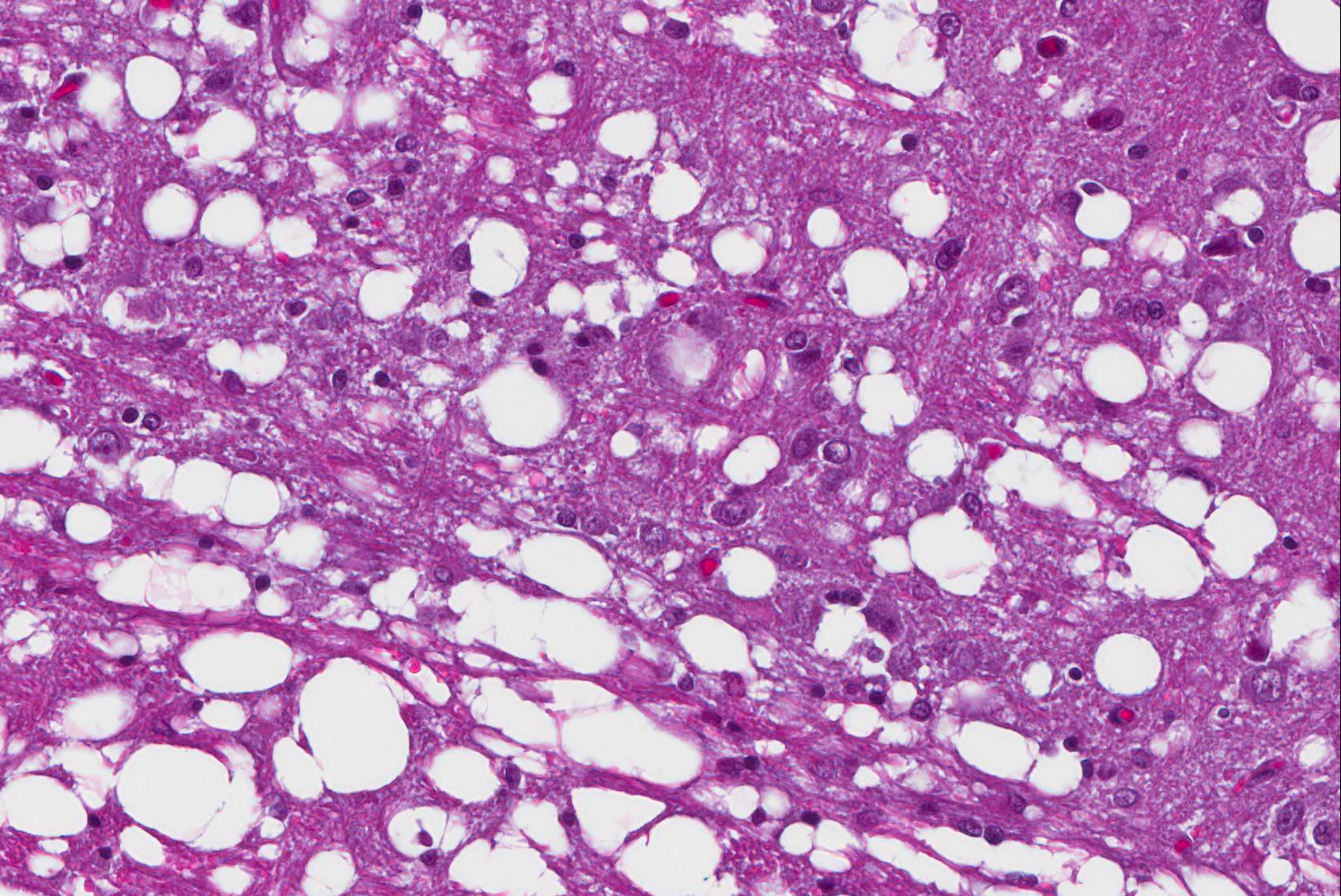

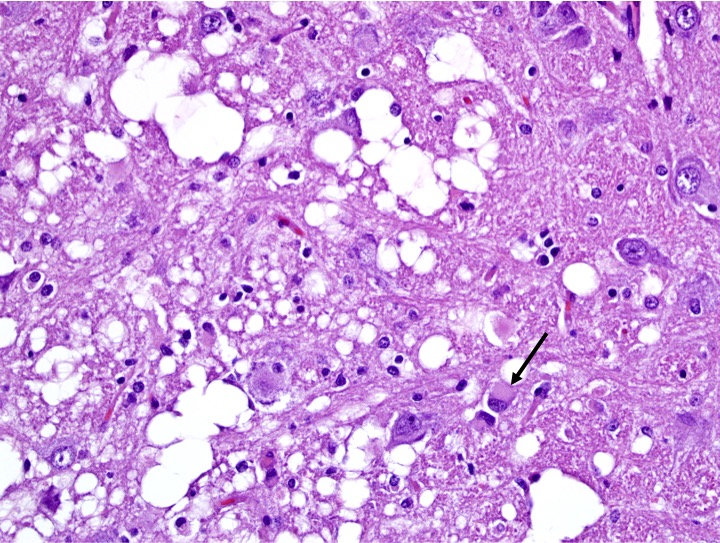

Affecting white matter throughout the examined sections of central nervous system are regions of myelin degeneration. These areas are characterized predominantly by multifocal to clustered, variably sized (approximately 6-60 um-diameter), clear vacuoles (spongiosis), with occasional wispy residual eosinophilic myelin strands and subtle regional pale staining (rarefaction). There are mildly increased interspersed small basophilic glial cells (astrocytosis) with occasional satellitosis, few eosinophilic swollen axons (spheroids), rare vacuolated gitter cells and digestion chambers, and rare eosinophilic reactive astrocytes (gemistocytes). The myelin vacuolation is marked and variably symmetrical within the brainstem, is moderate and more unilaterally predominant within the cerebral cortex corona radiata, and is mild and scattered within the internal capsule, thalamus, midbrain, cerebellar white mater, spinal cord (thoracic, predominantly ventral funiculi), and optic nerve.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Brain and spinal cord, white matter: Myelin degeneration, multifocally extensive, mild (thalamus, optic nerve, spinal cord) to moderate (cerebral cortex, cerebellum) to marked (brainstem), with prominent spongiosis, mild gliosis, and rare axonal degeneration.

Contributor’s Comment: This case demonstrates lesions of leukoencephalomyelopathy typical of “Wobbly Hedgehog Syndrome”, characterized by demyelinating changes affecting the brain and spinal cord. This syndrome is a progressive neuropathy of unknown etiology that affects African hedgehogs and is considered to have a familial tendency.

Wobbly Hedgehog Syndrome (WHS) has been recognized since the mid-1990s and is reported to affect approximately 10% of pet African hedgehogs in North America. The predominant clinical signs of WHS are progressive ataxia and paralysis, with onset often under two years of age. Disease progression is variable, but complete paralysis often occurs within 15 months. Other noted clinical abnormalities include tremors, exophthalmos, scoliosis, seizures, muscle atrophy, and self-mutilation.4 In most cases, the progression of paralysis is ascending to tetraplegia. Weight loss is common and may relate to dysphagia in later stages of disease. Skin abrasions affecting feet and ventral body can relate to loss of motility. As in this case, affected animals are often euthanized due to quality of life concerns.

Histopathology is required for definitive diagnosis of WHS, with characteristic vacuolation of the white matter tracts of the brain (cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem) and spinal cord. Lesions are considered to begin with myelin loss, and progress variably to secondary axonal and even neuronal degeneration. In this case, myelin degeneration predominated, with minor axonal degeneration variably evident across sections. Degeneration of lower motor neurons of the ventral horns of the spinal cord, demyelination of ventral spinal rootlets, and neurogenic muscle atrophy are also reported.4 The peripheral nervous system is unaffected. Hepatic lipidosis of varying severity has also been reported in some cases; in the animal of this report hepatocellular lipid vacuolation was mild.

The etiology of WHS is unknown. However, clustered cases and pedigree analysis suggest a hereditary basis. Relatives of this affected hedgehog had also succumbed to neurologic disease with pathologic findings supportive of WHS. Due to familial tendency, breeding hedgehogs with signs of WHS or their close relatives has been discouraged.4 No treatments (antibiotics, vitamins and supplements, physical therapy regimes, etc.), have been confirmed to alter the course of disease.

Although there are no reports of WHS transmission between unrelated hedgehogs, an infectious cause is not entirely excluded. A similar paralytic and demyelinating syndrome has also been reported in European hedgehogs, but with slightly different histologic and epidemiologic features, for which a viral etiology was suspected.7 More recently, nonsuppurative encephalitis with vacuolation of the white matter was reported in conjunction with positive detection of pneumonia virus of mice (family paramyxoviridae) in an African hedgehog suspected of WHS, but the relationship between the disease findings and links to causality require further investigation.6

Demyelinating conditions of animals and humans may be acquired or inherited/genetic. These diseases result from abnormalities affecting myelin sheaths or myelin forming cells. Axonal or neuronal degeneration is a secondary occurrence. Causes of acquired demyelination include: infectious agents (e.g., canine distemper virus and small ruminant lentiviruses), immune-mediated inflammation (e.g., multiple sclerosis in humans), metabolic derangements (e.g., central pontine myelinosis associated with rapid correction of hyponatremia in various species, and hepatic encephalopathy in various species), and toxic exposures (e.g., hexachlorophene, stypandrol, and others in various species).2,4-6 In some cases, hypoxia/ischemia and compressive lesions may also predominantly affect oligodendrocytes and myelin sheaths.5 Hereditary demyelinating conditions include identified genetic defects in humans (e.g., Canavan’s disease leukodystrophy due to mutation causing deficiency of aspartoacylase enzyme) and animals (e.g., canine spongiform leukoencephalomyelopathy in Shetland sheepdogs and Australian cattle dogs associated with cytochrome b mitochondrial DNA mutation; and maple syrup urine disease in Hereford, polled Hereford, and polled Shorthorn calves, linked to autosomal recessive mutation causing deficiency in branched-chain alpha-ketoacid decarboxylase complex). Additionally, multiple other presumed heredofamilial conditions causing myelin vacuolation in animals are reported for which specific genetic links are yet to be confirmed (e.g., in horned and polled Hereford calves, Samoyed and Border Terrier puppies, Egyptian Mau and ragdoll cats, and Silver Foxes).2,4

Other reported causes of progressive neurologic signs in hedgehogs include brain tumors (e.g., astrocytoma, microglioma, mixed glioma), intervertebral disk disease, and systemic diseases such as hepatic encephalopathy.1,4,8 None of these conditions was apparent in this case.

JPC Diagnosis: There were two different sections submitted:

- Brainstem, white matter: Myelin degeneration, bilaterally symmetrical, severe with neuronal degeneration and gliosis, African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris), hedgehog.

- Cerebrum, diencephalon, corona radiata: Myelin degeneration, bilaterally symmetrical, moderate.

Conference Comment: Hedgehogs and gymnures belong to the order Insectivora and make up the Erinaceidae family. There is very little reported infectious diseases in the African (Atelerix albiventris) or European (Erinaceius europaeus) hedgehog. Of note, enteritis caused by Salmonella sp., pneumonia caused by Corynebacterium sp., and upper respiratory disease caused by Pasteurella sp. and Bordetella bronchiseptica are the most frequent offenders. Additionally, insectivores are potential reservoirs for bloodborne pathogens that are transmitted by parasite vectors such as: Rickettsia spp., Borrelia burgdorferi, Babesia microti, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Fungal diseases reported include: adiaspiromycosis, cryptococcosis, paecilomycosis, histoplasmosis, and dermatophytosis. Viral diseases are extremely rare, but there have been reported cases of infection with herpes simplex virus 1 in African and European hedgehogs.3

Neoplasia is the most common of the noninfectious diseases in hedgehogs with malignant mammary adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and oral squamous cell carcinoma being most frequent. In African hedgehogs specifically males over one-year-old there is a high incidence of cardiomyopathy which is usually diagnosed late in the disease process at which time it is often fatal.3

Clinical neurologic signs in hedgehogs (incoordination, inability to roll into a ball, seizures, paralysis) are often diagnosed (even in clinical settings) as “wobbly hedgehog syndrome” which is a progressive and potentially hereditary disease that results in myelin degeneration in the central nervous system. An important differential diagnosis is intervertebral disk disease which is much less common but has been reported in hedgehogs.3

Within examined sections of cerebral cortex, there are multifocal areas within the superficial cortex and pyriform lob which contain numerous bright red, shrunken neurons which were interpreted by the JPC staff and moderator as acutely necrotic; a minimal glial reaction was present. This change is most consistent with ischemic neuronal necrosis; the necrotic neurons do not appear to be associated with areas of white matter degeneration and may represent a second concurrent disease process.

Contributing Institution:Wildlife Conservation Society

www.wcs.org

References:

- Benneter SS, Summers BA, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, et al. Mixed glioma (oligoastrocytoma) in the brain of an African hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). J Comp Pathol. 2014;151:420-424.

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:250-406.

- D’Agostino J. Insectivores (insectivora, macroscelidea, scandentia). In: Miller RE, Fowler ME, eds. Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine. 8. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:275-281.

- Graesser D, Spraker TR, Dressen P, et al. Wobbly hedgehog syndrome in African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix). J Exotic Pet Med. 2006;15(1):59-65.

- Love S. Demyelinating diseases. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1151-1159.

- Madarame H, Ogihara K, Kimura M, et al. Detection of pneumonia virus of mice (PVM) in an African hedgehog (Atelerix arbiventris) with suspected wobbly hedgehog syndrome. Vet Microbiol. 2014;173:136-140.

- Palmer AC, Blakemore WF, Franklin RJM, et al. Paralysis in hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) associated with demyelination. Vet Rec. 1998;143:550-552.

- Raymond JT, Aguilar R, Dunker F, et al. Intervertebral disc disease in African hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris): four cases. J Exotic Pet Med. 2009;18(3):220-223.