Signalment:

Ultrasonographically there was an irregular cavitated mass located cranially of the kidneys of about 30 cm in diameter. Renal parenchyma was only partially recognizable by ultrasound. The urinary bladder was unremarkable. Blood analysis revealed marked azotemia, elevated creatinine, hyperproteinemia with hyperglobulinemia and hyperfibrinogenemia.

Due to the clinical symptoms, the age of the gelding and additional orthopedic problems (founder) as well as a poor prognosis due to the suspected renal neoplasia, the animal was euthanized and submitted for necropsy.

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

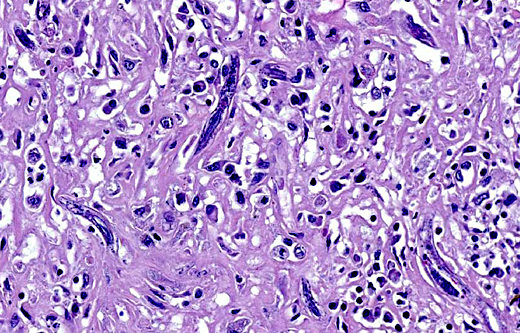

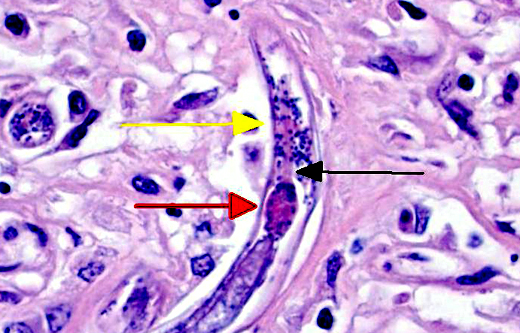

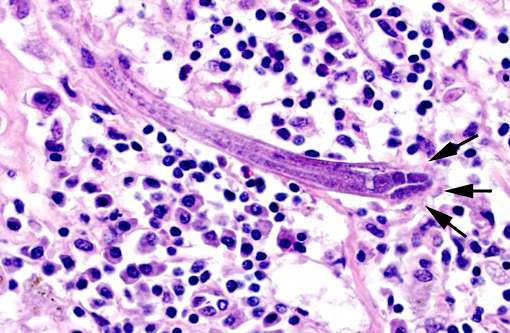

Sometimes a dorsoflexed uterus, occasionally with uninucleated eggs, and a rhabditiform esophagus with corpus, isthmus and bulb can be seen. Eggs, measuring about 15 x 20 μm are occasionally observed free within the inflamed tissue. Multifocally, smaller forms of the parasites with rhabditiform esophagus and internal granular structures can be found (larvae). Parasites are multifocally surrounded by areas of lytic necrosis characterized by replacement of tissue with nuclear and cellular debris. Intralesional vessels are dilated (hyperemia) and in one location parasites, surrounded by inflammatory cells, are found within a medium sized artery. At the margins of the granuloma are moderate numbers of macrophages containing a yellow-brown globular pigment (hemosiderin).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

| Creatinine | 260 μmol/l (ref. 69-155 μmol/l) |

| Urea | 11.41 mmol/l (3.18-7.31 mmol/l) |

| Serum protein | 90.7 g/l (58-74 g/l) |

| Albumine | 26.1 g/l (29.93-37.88 g/l) |

| Globuline | 64.6 g/l (23.07-42.09 g/l) |

| Fibrinogen | 5.14 g/l (1.25-3.29 g/l) |

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

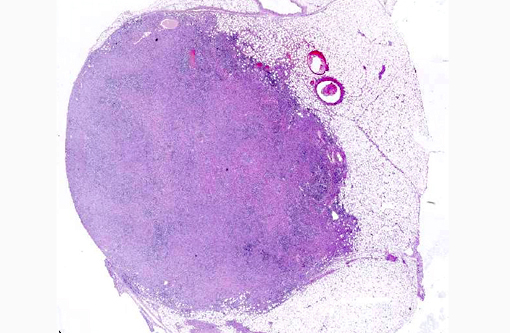

It has been shown that only female worms and larvae induce lesions. In the kidneys, the parasite causes multifocal to coalescing granulomas containing numerous larval and adult rhabditiform nematodes and occasional embryonated eggs. Macroscopically, these granulomas often resemble neoplasms.(9)

The nematodes are 15-20 μm in diameter, 250-430 μm in length and have a thin, smooth cuticle. They possess a platymyarian-meromyarian musculature, a pseudocoelom and a rhabditiform esophagus composed of a corpus, isthmus and bulb. The intestinal tract is lined by uninucleate, low cuboidal cells and a single genital tube/uterus containing one egg/ova.(5)

Other important lesions in horses are severe encephalitis and myelitis,(1,6,10) orchitis,(4) osteomyelitis(13) and posthitis.(11) Sometimes disseminated disease can develop.(7)

There are different hypotheses regarding the life cycle and the way of transmission of the nematode. Oral ingestion, inhalation or wound infections with nematode stages are suggested.(2) In one case vertical transmission on the colostral way from the dam to the foal was described.(10,15)

Successful surgical therapies of cases with localized lesions are recorded, but it is possible that the parasites may survive within the granulomas; however, in the CNS the parasites can survive because anthelmintics do not easily cross the blood-brain barrier.(3)

In cases of renal halicephalobosis, also the case in the presented horse, azotemia and renal failure as well as hematuria can be observed. Parasitic lesions in tissues other than kidney and lymph node were not detectable in our case.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

There are a number of migrating nematodes capable of inducing disease in the equine. While H. gingivalis is readily distinguishable, infections of Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus equinus, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Setaria spp., and Draschia megastoma can all manifest into a variety of clinical presentations to include neurologic signs and thus may be worthy of consideration.(8) H. gingivalis has more affinity for the kidneys, lymph nodes and central nervous system; therefore infected animals most often present with renal signs as in this case or neurologic symptoms such as ataxia, circling, loss of balance, and head tremors.(2)

There are nine species of Halicephalobus, though only H. gingivalis is known to cause disease in animals.(2) Its pathogenesis is largely unproven, including routes of infection. Hematogenous spread is widely accepted and supported by the presence of larva within arteries in this case. It is interesting, however, why it has predilection for certain tissues and often spares organs such as the liver and spleen. Only adult females, larval stages, and eggs have been identified in tissue sections, indicating the likelihood of parthenogenetic reproduction.(2,7) Many details of the pathogenesis of this rarely reported parasitic infection remain undetermined.Â

References:

1. Akagami M, Shibahara T, Yoshiga T, Tanaka N, Yaguchi Y, Onuki T, et al. Granulomatous nephritis and meningoencephalomyelitis caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis in a pony gelding. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69:1187-1190.

2. Bryant UK, Lyons ET, Bain FT, Hong CB. Halicephalobus gingivalis-associated meningoencephalitis in a Thoroughbred foal. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006;18:612-615.

3. Ferguson R, van Dreumel T, Keystone JS, Manning A, Malatestinic A, Caswell JL, et al. Unsuccessful treatment of a horse with mandibular granulomatous osteomyelitis due to Halicephalobus gingivalis. Can Vet J. 2008;49:1099-1103.

4. Foster RA, Ladds PW. Male genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed., Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2007;(3):587.

5. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissue Washington, DC: Registry of Veterinary Pathology/ Armed Force Institute of Pathology.1999, revised 2006.

6. Hermosilla C, Coumbe KM, Habershon-Butcher J, Sch+�-�niger S. Fatal equine meningoencephalitis in the United Kingdom caused by the panagrolaimid nematode Halicephalobus gingivalis: case report and review of the literature. Equine Vet J. 2011;43:759-763.

7. Isaza R, Schiller CA, Stover J, Smith PJ, Greiner EC. Halicephalobus gingivalis (Nematoda) infection in a Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2000;31:77-81.

8. Jung JY, Lee KH, Rhyoo MY, Byun JW, Bae YC, Choi E, et al. Meningoencephalitis caused by Halicephalobus gingivalis in a thoroughbred gelding. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76:281-284.

9. Maxie MG, Newman SJ. Urinary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2007;(2):498.

10. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2007;(1):437-444.

11. Muller S, Grzybowski M, Sager H, Bornand V, Brehm W. A nodular granulomatous posthitis caused by Halicephalobus sp. in a horse. Vet Dermatol. 2008;19:44-48.

12. Papadi B, Boudreaux C, Tucker JA, Mathison B, Bishop H, Eberhard ME. Halicephalobus gingivalis: a rare cause of fatal meningoencephalomyelitis in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:1062-1064.

13. Teifke JP, Schmidt E, Traenckner CM, Bauer C. [Halicephalobus (Syn. Micronema) deletrix as a cause of granulomatous gingivitis and osteomyelitis in a horse]. Tieraerztl Prax Ausg G Grosstiere Nutztiere. 1998;26:157-161.

14. Wilkins PA, Wacholder S, Nolan TJ, Bolin DC, Hunt P, Bernard W, et al. Evidence for transmission of Halicephalobus deletrix (H. gingivalis) from dam to foal. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:412-417.