Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 14

15 January 2020

Dr.

Neel Aziz

Supervising Veterinary Pathologist

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

National Zoological Park

Washington DC, 20008

CASE II: 2926 (JPC 4118632).

Signalment: 7-year-old, male, Asian small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinerea).

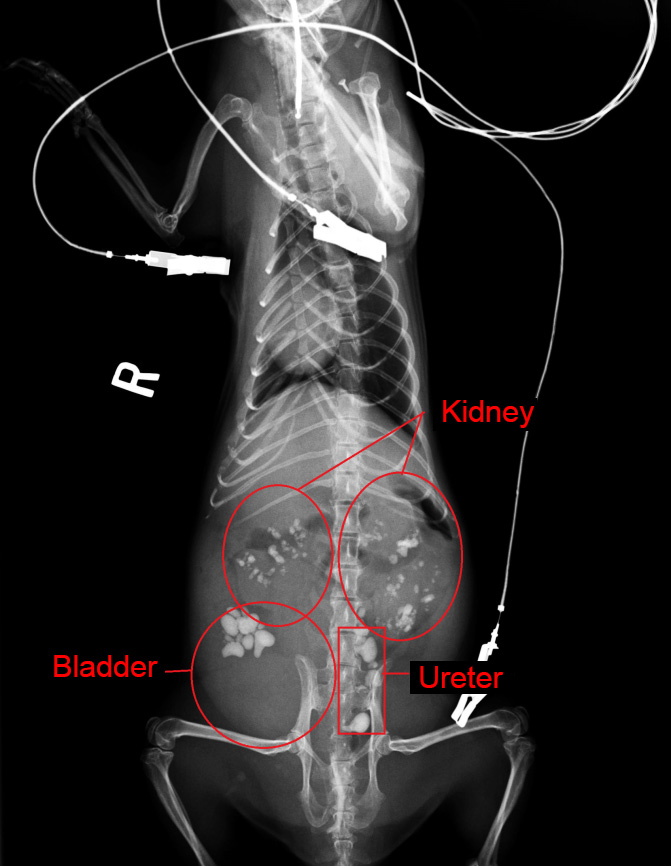

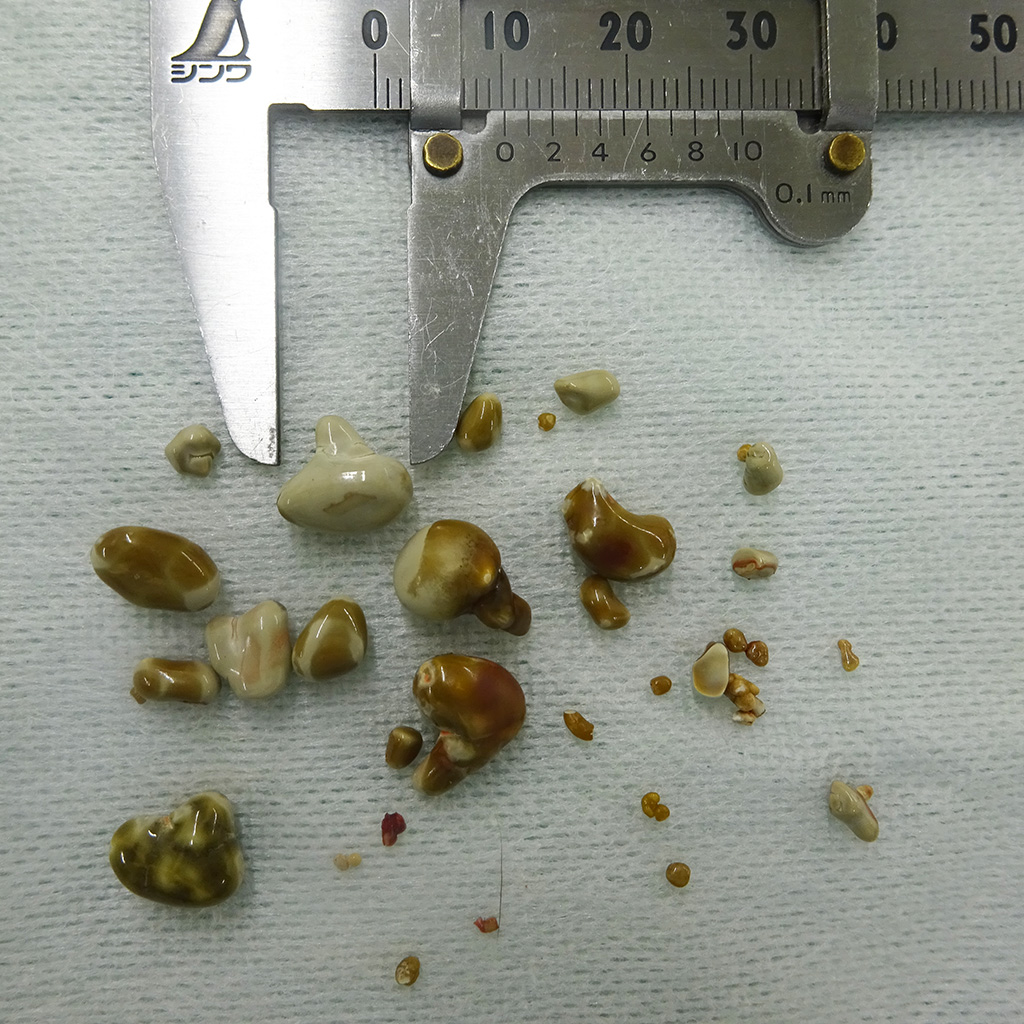

History: This otter was presented to a veterinary hospital with a short history of anorexia. Marked increases of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, inorganic phosphorus, and ammonia were noted in serum biochemistry. Radiographs indicated numerous (more than 20) calculi in both kidneys, ureters, and urinary bladder. Lithotomy was performed, and approximately 30, up to 10.2 mm in diameter, yellowish-green to white calculi were removed from the ureters and urinary bladder. The otter persistently showed anorexia and died at seventh day after the surgery.

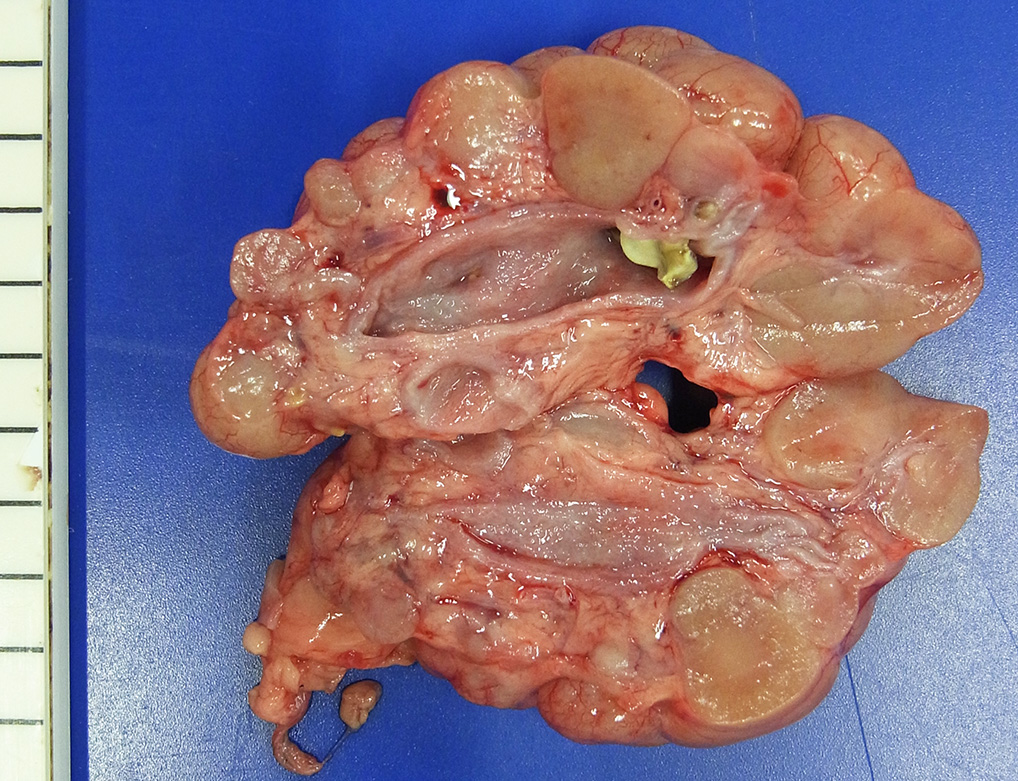

Gross Pathology: The animal showed mild emaciation and dehydration at necropsy. Multiple yellowish-green calculi, maximum 6 mm in diameter, were noted in the renal pelves, ureters, and urinary bladder. Both ureters dilated moderately. Some renal lobes were mildly atrophic with fibrosis.

Laboratory results:

Blood urea nitrogen, 215.2 mg/dl (reference range: 9.2 ? 29.2 mg/dl in dogs); creatinine, 6.6 mg/dl (0.4 ? 1.4 mg/dl in dogs); inorganic phosphorus, 25.8 mg/dl (1.9 ? 5.0 mg/dl in dogs); ammonia, 247 μg/dl (16 ? 75 μg/dl in dogs).

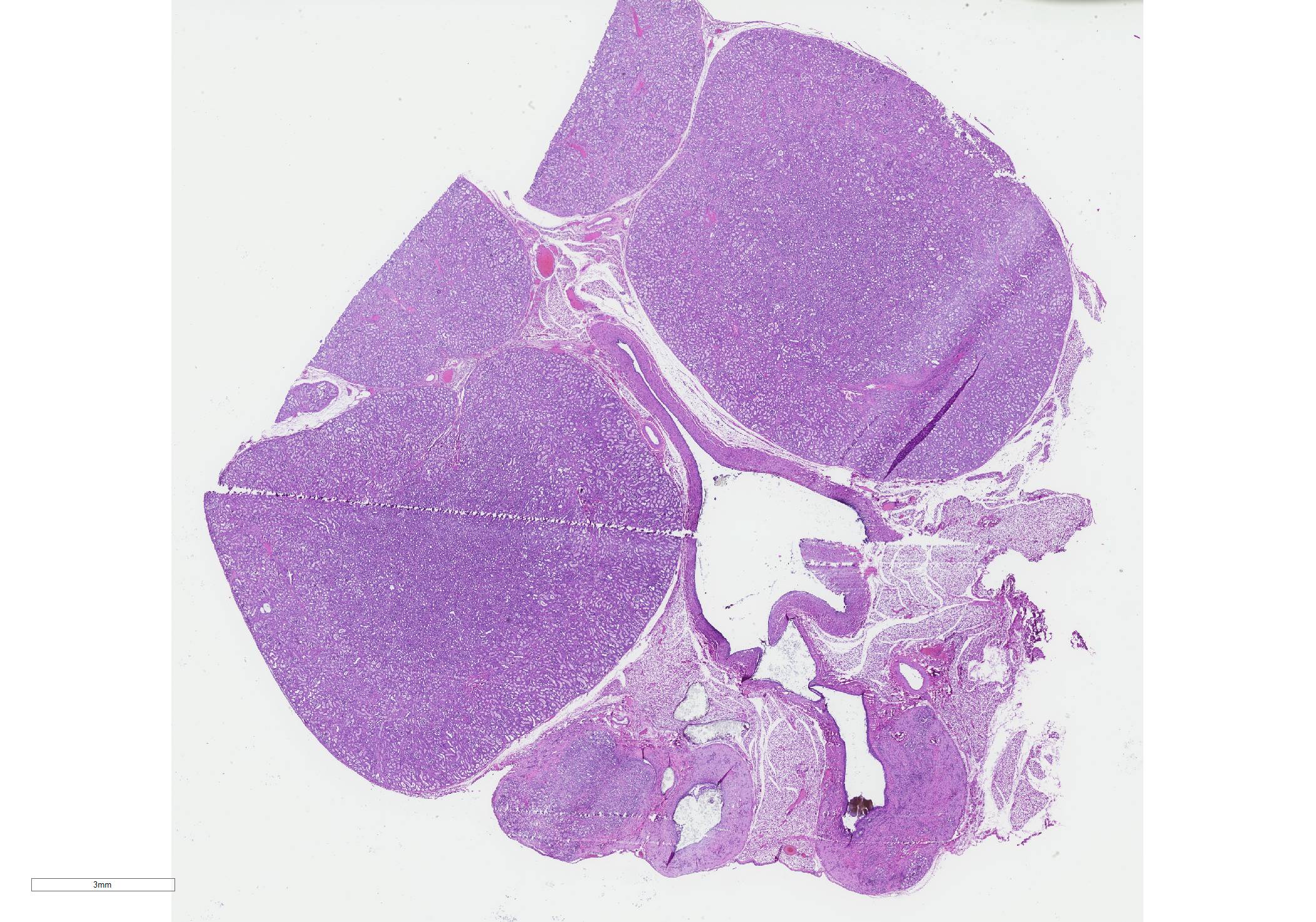

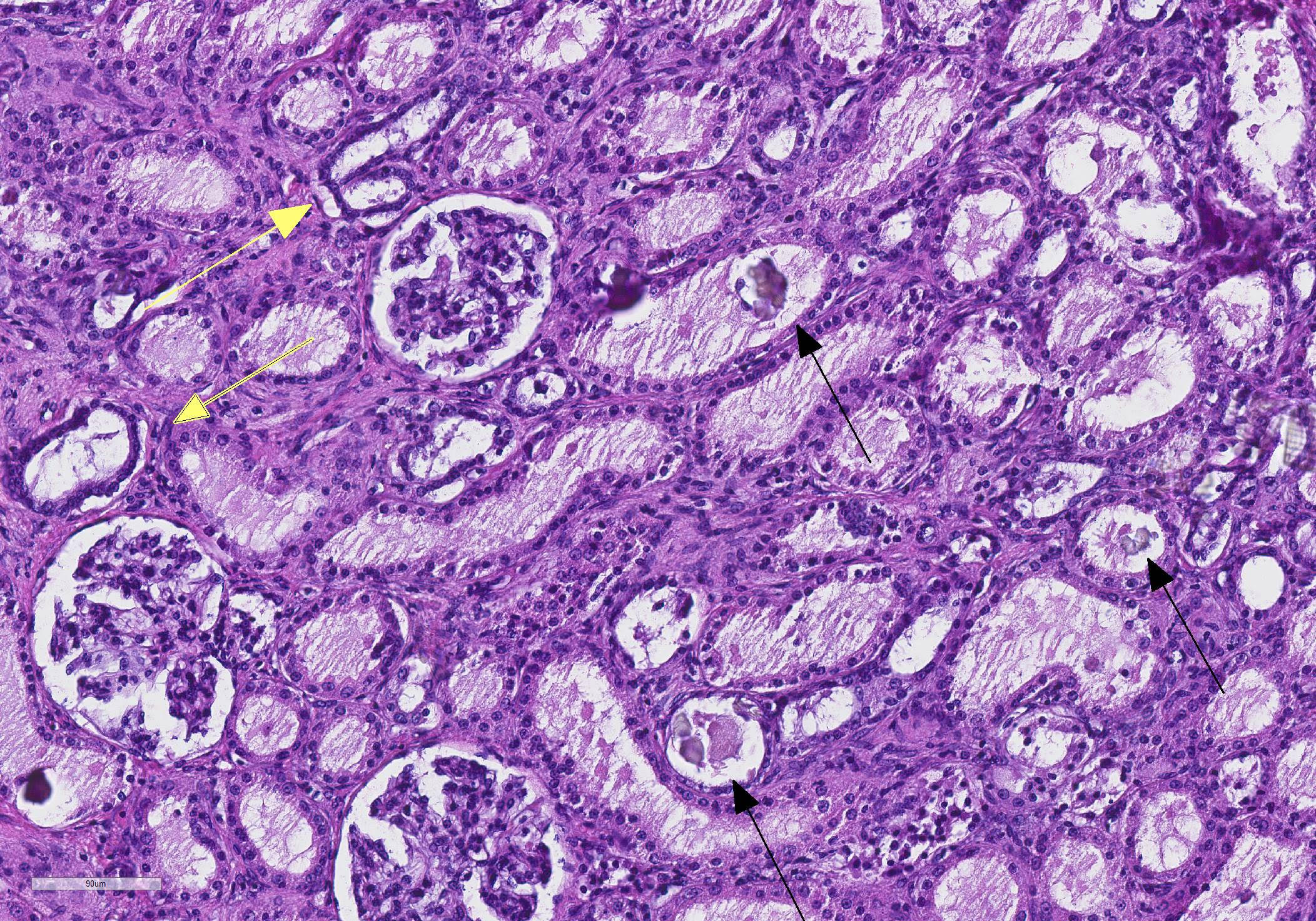

Microscopic Description: Kidney: Diffuse moderate interstitial fibrosis is observed. A few lymphocytes infiltrate into the interstitium of the medulla. Prismatic pale yellowish crystals scatter in the lumina of renal tubules, collecting ducts, and dilated renal pelvis. These crystals show birefringence under polarized light. Degeneration and necrosis of the tubular epithelial cells and intraluminal protein cast formation are noted in the medulla.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Kidney: Oxalate urolithiasis and nephropathy, chronic, multifocal, moderate.

Contributor Comment: Urolithiasis is frequently observed in otters such as Asian small-clawed otters (Aonyx cinerea), North American river otters (Lontra canadensis), or Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra).1-3,6,8 It has been reported that 16.7% of free-ranging North American river otters5 and 23.4% of free-ranging Eurasian otters1 had uroliths. The prevalence of uroliths appears to increase in captive populations, as urolithiasis has been found in 66.1% of captive Asian small-clawed otters2 and 64.7% of captive Eurasian otters1.

In Asian small-clawed otters, the majority of affected individuals had bilateral renal calculi.2 In addition, about one-thirds of individuals with renal calculi also had cystic calculi.2 Ureteral obstruction due to uroliths causes dilation of ureters, hydronephrosis, and pyelonephritis.4 In the affected animals, renal disease can be the cause of, or a contributing factor in, the deaths.2 Calculi are mainly composed of calcium oxalate or ammonium acid urate.1,2,4

In North American river otters, bilateral renal calculi are not common, and the majority of otters with calculi are generally healthy without gross renal abnormalities.5 Only severely affected animals showed bilateral calculi or ureteral obstruction.3 Although calculi have not been systematically analyzed so far, calcium phosphate and urate have been reported as a primary component of the calculi.3,6

In Eurasian otters, only one-thirds of total cases showed bilateral renal calculi and calculi were restricted to within the kidney in the majority of affected animals.8 Only a few severely affected individuals showed ureteral or cystic calculi.1,8 The main component of calculi is ammonium acid urate.1,8

Gender does not affect the susceptibility to urolithiasis in otters.1,2,6 Meanwhile, age appears to relate to the prevalence of urolithiasis or disease severity. The positive rate or the number of uroliths increase with age in North American river otters and Eurasian otters.1,6,8 In Asian small-clawed otters, renal disease was more frequently reported as the cause of death in older individuals.2

Although husbandry, diet, genetics, chronic infections, or metabolic disorders have been suggested as contributing factors, the exact mechanisms for the high prevalence of urolithiasis in otters have remained unknown. Since the prevalence of urolithiasis is higher in captive populations, it is possible that the captive diet may contribute to urolithiasis to some extent.2 Meanwhile, as a significant portion of free-ranging individuals also have uroliths, there might be a predisposing factor to urolithiasis in otters. It is noteworthy that the main components of uroliths differ among species of otters as with the species-dependent difference in stone composition in dogs.6 In addition, disease severity is also different among species, i.e., Asian small-clawed otters show severer lesions compared with North American river otters or Eurasian otters. Therefore, genetic factors predisposing to urolithiasis might also differ among species. As effective, preventive measures against urolithiasis in otters have not been established, periodic evaluations of uroliths would be important in captive populations such as routine abdominal radiographs, evaluation of serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, and urinalysis.2

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Comparative Pathology, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University. https://www.vetmed.hokudai.ac.jp/

JPC Diagnosis: Kidney, pelvis: Oxalate urolithiasis, diffuse, severe, with hydronephrosis, intratubular oxalate crystals, and diffuse moderate chronic interstitial nephritis.

JPC Comment: The contributor provides an excellent review of urolithiasis in captive otters, which can be a significant management jproblem in zoological collections. Table 1 is an recapitulation of the various types of uroliths and prevalence in otter and wolverines.

|

Mustelid sp. |

Captive or Free Ranging |

Stone Type |

Reported Prevalence |

Associated Lesions |

Possible Risk Factors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Asian small clawed otter |

Captive |

Mix of urate and calcium oxalate |

66%?89% |

Not reported |

Older age (>2 years) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eurasian otter |

Free ranging |

Ammonium acid urate |

10.2% |

Nephrolithiasis |

Dietary purine intake, protein quality, and digestibility |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

North American river otter |

Free ranging |

Calcium phosphate |

16.2% |

Not reported |

Older age, capture location |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

North American river otter |

Free ranging |

Uric acid |

0.33% |

Bilateral nephrolithiasis, expanded renal calyces, marked hydroureter, mild renal medullary loss, and cortical tubular atrophy |

Not reported |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wolverine |

Free ranging |

Ammonium acid urate with magnesium ammonium phosphate and calcium phosphate |

8.9% |

Nephroliths were unilateral in 87.5% of cases. |

Older age (>2 years) males |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1. Urolithiasis in Otters and Wolverines. From Terio, McAloose. St Leger eds., Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals., 2019.10

Other mustelids also develop uroliths on a fairly frequent basis, which may result in obstruction. Struvite urolithiasis is well-documented in ferrets and farmed mink. In pet ferrets, protein composition (with higher amounts of plant proteins than a wild mustelid would normally take in) are thought to be one of several causative factors. In farmed mink, urolithiasis is likely multifactorial, as the sexes have distinct seasonal predisposition to development of uroliths, with pregnant females developing stones in the spring, and male kits in the fall. Concurrent bacterial infection with Staphylococcus intermedius is common in mink, but bacterial infection is uncommon in the affected ferret.10

Oxalate nephrosis/nepholithiasis/urolithiasis

is well known in a number of other species. Cheetahs, and less commonly

cougars, jaguards and leopards may develop oxalate nephrosis with crystal

development in tubules, acute renal failure, azotemia and death. Toxicosis, such

as may be seen with ethylene glycol ingestion has been ruled out in most cases,

but the pathogenesis of this disease remains unclear.9

Marsupials also commonly suffer from oxalate nephrosis, which is best known in

the koala, but may also be seen in wallabies, possums, and potoroos. Mild

oxalate neprhosis is a common finding in koalas in collections around the

world, so dietary contributions are unlikely. Once again, the pathogenesis of

oxalate nephrosis in these species is unknown.5

In domestic species, oxalate uroliths are the second most common type of calculus with small breeds such as miniature poodles, miniature schnauzers, Bichons, Lhasa Apsos and Shih-Tzus being predisposed. They may be encountered in a numbr of conditions other than ethylene glycol toxicosis, including hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, and increased levels of endogenous and exogenous steroids. In ruminants (and in koalas), oxalate-degrading bacteria are a common flora of the rumen and lower tract, likely lessening the effect of a high-oxalate diet in certain locales.

Participants identified a focal area of extreme cortical and medullary atrophy of one of the lobules within the section of kidney adjacent to a large oxalate crystal. The area was interpreted as an area of obstruction, if not actual pressure necrosis, and focal hydronephrosis.

References:

1. Bochmann M, Steinlechner S, Hesse A, Dietz HH, Weber H. Urolithiasis in free-ranging and captive otters (Lutra lutra and Aonyx cinerea) in Europe. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2017;48:725-731.

2. Calle PP. Asian small-clawed otter (Aonyx cinerea) urolithiasis prevalence in North America. Zoo Biol. 1988;7:233-242.

3. Grove RA, Bildfell R, Henny CJ, Buhler DR. Bilateral uric acid nephrolithiasis and ureteral hypertrophy in a free-ranging river otter (Lontra canadensis). J Wildl Dis. 2003;39:914-917.

4. Higbie CT, Carpenter JW, Armbrust LJ, Klocke E, Almes K. Nephrectomy in an Asian small-clawed otter (Amblonyx cinereus) with pyelonephritis and hydronephrosis secondary to ureteral obstruction. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2014;45:690-695.

5. Higgins D, Rose K, Spratt D. Monotremes and marupials. . In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals Terio KA, McAloose D, St Leger J eds., 2019; London: Associated Press, p. 458.

6. Niemuth JN, Sanders CW, Mooney CB, Olfenbuttel C, DePerno CS, Stoskopf MK. Nephrolithiasis in free-ranging North American river otter (Lontra Canadensis) in North Carolina, USA. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2014;45:110-117.

7. Roe K, Pratt A, Lulich J, Osborne C, Syme HM. Analysis of 14,008 uroliths from dogs in the UK over a 10-year period. J Small Anim Pract. 2012; 53: 634-640.

8. Simpson VR, Tomlinson AJ, Molenaar FM, Lawson B, Rogers KD. Renal calculi in wild Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) in England. Vet Rec. 2011;169:49.

9. Terio KA, McAloose D, Mitchell E. Felidae. In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals Terio KA, McAloose D, St Leger J eds., 2019; London: Associated Press, p. 268.

10. Williams BH, Burek Huntington KA, Miller M. Mustelids. In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals Terio KA, McAloose D, St Leger J eds., 2019; London: Associated Press, p. 281.