Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 3

4 September, 2019

Dr. Corrie Brown, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVP

Josiah

Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor

University Professor

Department

of Pathology

University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine

2200 College Station Road Athens, GA, 30602

CASE II: 14-102 (JPC 4048789).

Signalment: 8 month old purpose bred Dorset cross ewe (Ovis aries)

History: Received from supplier 17 days prior to euthanasia. Vaccinated for CD&T, pasteurellosis and orf 6 months prior. Negative Q fever serology. Dewormed with an avermectin at time of shipping. Eleven days after arrival she developed a 5 cm diameter subcutaneous abscess of the cranioventral neck near the angle of the mandible. FNA was performed and a sample was submitted for culture. The next day the abscess had ruptured and incompletely drained. When culture results were received, the decision was made to euthanatize.

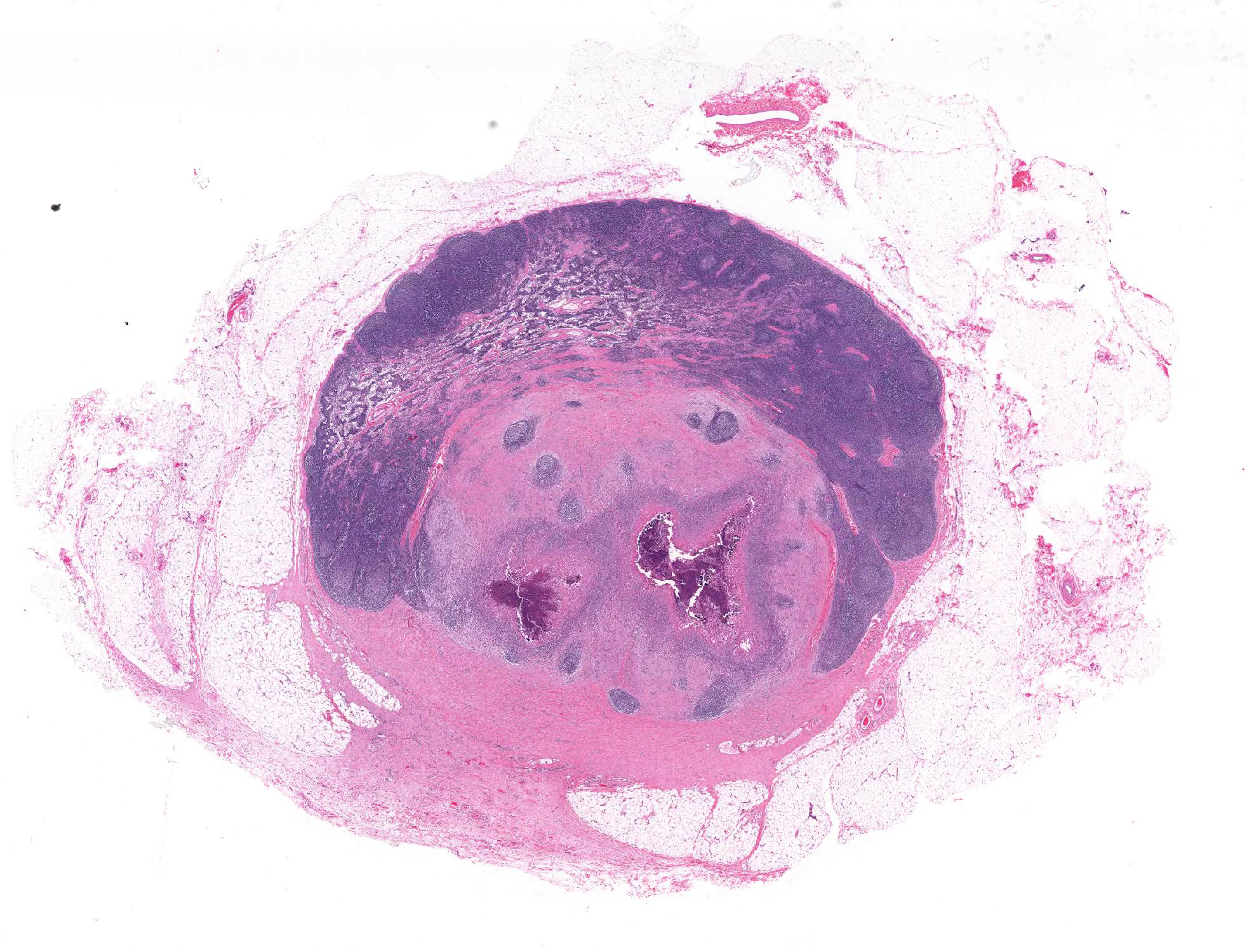

Gross Pathology: At necropsy there was a firm fibrous subcutaneous swelling at the angle of the right mandible with a cutaneous scab. The left submandibular lymph node was firm (fibrosis) and exuded thick green material on cut section. There were several small (2-5 mm) tan nodules in the lungs and liver.

Laboratory results: Gram Stain of FNA: Large numbers of Gram positive rods.

Aerobic culture of abscess (PADLS PVL): Heavy growth of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis.

Microscopic Description:

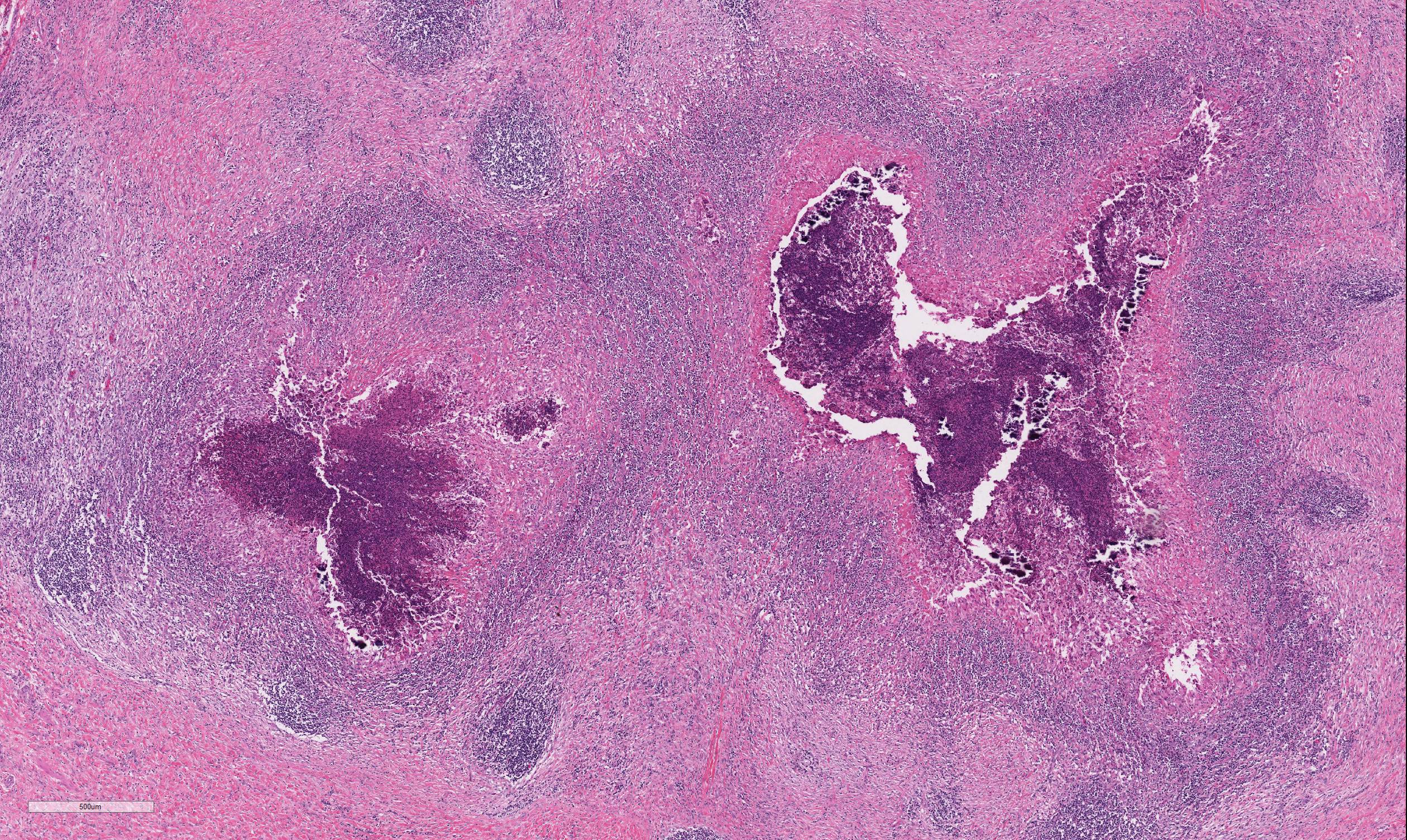

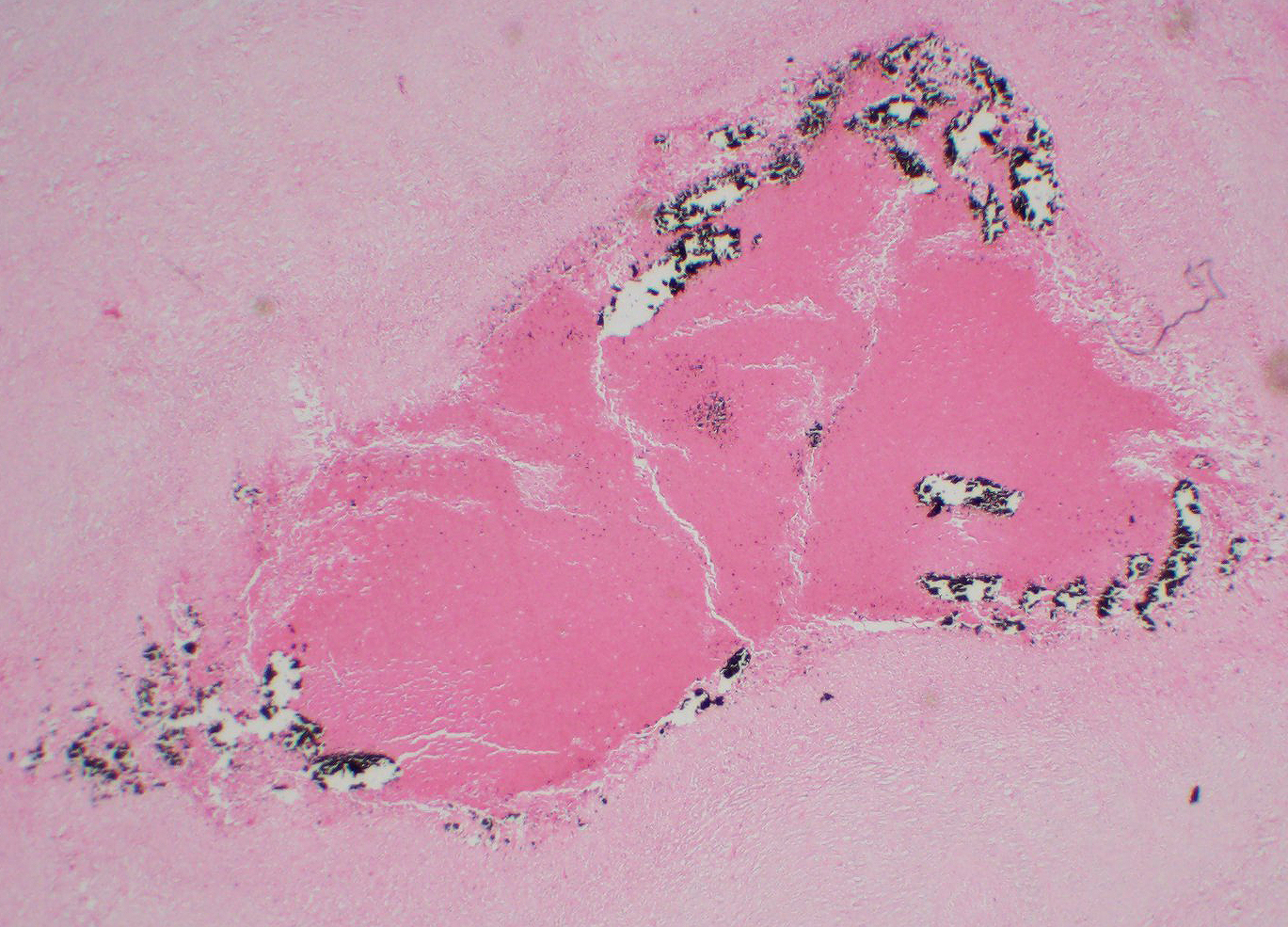

The lymph node is partially effaced by one large or several coalescing discrete, incompletely encapsulated pyogranulomas with a large central core of abundant necrotic cellular debris and degenerate neutrophils with numerous coarse basophilic refractile mineralized concretions. This is surrounded by a layer of moderate numbers of epithelioid and foamy macrophages with occasional multinucleate giant cells, mostly of the Langhans type. Peripheral to this are moderate to large numbers of plasma cells with fewer lymphocytes and macrophages, and rare Mott cells. There is abundant nascent (immature) and mature fibrosis circumscribing the lesion. The lymph node is mildly reactive with pale germinal centers, paracortical lymphoid hyperplasia, and medullary sinus plasmacytosis.

Similar pyogranulomas were present in the liver and lungs (tissue not submitted), often with prominent eosinophil infiltration.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lymph node, left

submandibular, pyogranuloma, focally extensive, chronic, moderate with

mineralization

Contributor Comment: Caseous lymphadenitis is a disease of small ruminants caused by infection with Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (C. ovis).1,5 The agent is so named for the gross and histologic similarity of the pyogranulomas to those of tuberculosis, including mineralization and caseation. The organism generally gains entry through cutaneous wounds (often related to shearing or castration), although none were present in this case. Given the lesion location, infection via a wound in the oral cavity is likely. Organisms localize in the local draining lymph node. Infections can also spread internally, commonly to the lungs (as in this case), making this animal unsuitable for research purposes. The organism can survive intracellularly within macrophages due to a leukotoxic surface lipid, and infections tend to be persistent but subclinical. The characteristic green color of the gross exudate is imparted by the accumulation of eosinophils in the lesions. Inspissation of the exudate over time produces the classic lamellated cheesy material.

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is a pleomorphic, gram-positive, non-motile, facultatively anaerobic member of the Actinomycetaceae.1,3 Members of this group are notable for the mycolic acid content of the cell walls and prolonged environmental persistence. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is closely related to C. diptheriae and C. ulcerans. There are two biochemically and genetically distinct biovars of C. pseudotuberculosis, biovar ovis (biotype 1) and biovar equi (biotype 2). The former is typically a pathogen of small ruminants and does not reduce nitrate; the latter is more commonly a pathogen of cattle and horses and does reduce nitrate. Infections in horses include pigeon fever (skeletal muscle abscesses) and ulcerative lymphangitis.4 Virulence factors for this organism include phospholipase D, a sphingomyelin-specific phospholipase, as well as mycolic acids within the cell wall.

Differential diagnosis for this case would include Trueperella (Arcanobacterium) pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus (botryomycosis), Actinobacillus lignieresii, and Mycobacterium bovis. Gram positive organisms of veterinary importance can be remembered by the acronym SCRAMBLED SCENT, encompassing the genera:

· Staphylococcus

· Clostridium

· Rhodococcus

· Actinomyces

· Mycobacterium

· Bacillus

· Listeria

· Erysipelothrix

· Dermatophilus

· Streptococcus

· Corynebacterium

· Enterococcus

· Nocardia

· Trueperella

Subcutaneous reactions to clostridial vaccines, particularly around the neck or scapula, can also be mistaken for CLA.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Comparative Medicine

Penn State Hershey Medical Center

http://www.hmc.psu.edu/comparativemedicine/

JPC Diagnosis: Lymph node: Pyogranuloma, focal.

JPC Comment:

The contributor

gives a concise review of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection

in small ruminants. This gram-positive facultative intracellular pathogen,

which may exhibit pleomorphism in tissue, such as coccoids and filamentous rods,2

is best known for abscess formation in small ruminants, also affects a wide

range of other species, including horses (as previously mentioned), cattle,

camelids, deer, and humans. The bacterium was first identified by the French

bacteriologist Edward Nocard from a cow, and three years later, by the

Bulgarian Hugo von Priesz from a ewe. For the next thirteen, it was referred

to as the Priesz-Nocard

bacterium, where upon it was renamed Bacillus

pseudotuberculosis in the atlas by prominent German bacteriologists Lehman

and Neuman. In the 1923 first edition of Bergey´s Manual of Determinative

Bacteriology it was placed in the genus of Corynebacterium, where it

remains today. It was at that time called Corynebacterium ovis, but

after discovered to cause infection in a number of species, reverted back to C.

pseudotuberculosis in 1948, by the sixth edition of that manual.1

In sheep,

infection usually follows wound infection, and at shearing time, infected

abscesses may be punctured, bacterial liberated in a common dip tank, and the

bacterium may invade shearing wounds on other sheep or even penetrate intact

skin. In addition to direct contact, the disease may also be spread by sheep

with established respiratory infections coughing on the open wounds of penmates.2

If the bacteria are not confined to and eliminated from the skin, the infection

may progress to draining nodes.6 Mature abscesses in the lymph nodes

of sheep may achieve a greenish lamellated In sheep, especially older sheep, the infection may progress from peripheral

lymph nodes to internal nodes or organs, especially the lungs, resulting in

chronic systemic disease referred to as the "thin ewe syndrome" (apparently

more common in the US than in other countries)1. The presence of

abscesses within nodes and carcass meat generally results in condemnation,

which, in countries which utilize lamb for religious celebration, may result in

a loss of $200 per animal to the purveyor. Many countries have strict

importation guidelines regarding contamination of small ruminants with this

bacterium. The importance of CLA vaccination is exemplified by the decrease in

CLA in Australia alone - in 1973, CLA among sheep in Western Australia was

estimated at 58%; following introduction of a CLA vaccine in 1983, similar

studies recorded a prevalence of 45%, which in turn dropped to 20% in 2002.1 In goats, lesions are more often severe, and abscesses tend to cluster in the

nodes of the face and neck. The liquid nature of abscessed nodes is

reminiscent of melioidosis (Burkholderia pseudomallei infection) in this

species.6 Other lesions associated with C. pseudotuberculosis in

sheep and goats include mastitis (presumably resulting from local spread from

abscessed supramammary nodes)1 and polyarthritis in young lambs, but

overall, the disease is rarely fatal, even in prolonged infection.6

Another disease caused by C. pseudotuberculosis in the horse is equine

folliculitis and furunculosis (also referred to as equine contagious acne, ,

equine contagious pustular dermatitis and "Canadian horsepox"). It is most often

seen at points of contact with tack in animals with pre-existent seborrheic

dermatitis, and likely represents secondary invasion by bacteria spread on

contaminated tack.1 The moderator, who did her PhD studying this agent, reviewed the various pathogenic factors which allow it to cause disease in a range of ruminants and horses. Like other higher bacteria, the presence of mycolic acid in the wall of the bacterium, which allows it to resist digestion in phagocytes also lends a unique property to colonies in culture â the ability to slide easily across the plate, known as "shuffleboard" coloniesâ. Another virulence factor, phospholipase D, is important for tissue invasion. In sheep and goats, phospholipase D allows the bacteria to invade through sphingomyelin-containing endothelium, allowing for extensive intravascular spread of the bacterium. In the biovar infecting horses, the bacterium do not possess sufficient phospholipase D for intravascular spread, and must be introduced in a wound, resulting in a slow progressive lymphangitis.

The moderator also described the synergistic hemolysis-inhibition titers (with a rather rude acronym) which were used in the 1980s for diagnosis of occult infection of C. pseudotuberculosis in small ruminants in Brazil. The synergistic hemolysis-inhibition test detects antibodies to an exotoxin of C. pseudotuberculosis by the inhibition of a synergistic hemolysis between the toxins of C. pseudotuberculosis and R. equi.

References: 1. Baird GJ,

Fontaine MC: Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and its role in ovine caseous

lymphadenitis. J Comp Pathol 2007:137(4):179-210. 2. Dorella FA, Pacheco LGC, Oliveira

SC, Miyoshi A, Azevedo. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis:

microbiology, biochemical proterties, pathogenesis and molecular studies of

virulence. Vet Res 2016; 17:201-218. 3 Soares SC, Silva A, Trost E, Blom

J, Ramos R, Carneiro A, et al.: The pan-genome of the animal pathogen

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis reveals differences in genome plasticity

between the biovar ovis and equi strains. PLoS One 2013:8(1):e53818. 4 Valentine BA, McGavin MD: Skeletal

Muscle. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary

Disease, Fourth Ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2007: 973-1039. 5 Valli VEO: Hematopoietic System.

In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals.

Fifth ed. Edinburgh: Saunders Elsevier; 2007: 107-324. 6. Valli VEO, Kiupel M. Bienzle D.

In. Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic

Animals. Sixth ed. Edinburg: Saunders, Elesevier, 2016, pp 204-208. onion-skin appearance

due to

recurrent and alternating episodes of suppuration and encapsulation; in goats,

the abscesses tend to demonstrate a more liquefied appearance. When the

infection reaches the lymph nodes, the condition is considered persistent and

lifelong.1