CASE IV:

Signalment:

8 year-old female alpaca (Vicugna pacos)

History:

The animal presented with a one-week history of lethargy, self-isolation from the herd, and progressive neurologic signs.

Gross Pathology:

Firmly adhered to the dura and compressing the left dorsolateral cerebrum, including the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes and causing rightward deviation of midline, is a 4.5 cm diameter, multilobulated, well demarcated, firm mass. On cut section the mass varies from pale to dark tan with multifocal regions of cavitation filled with clear, straw colored, viscous fluid. Additionally, there is moderate cerebellar herniation through the foramen magnum.

|

Figure 4-2. Cerebrum, alpaca. The mass in cut section infiltrates the underlying temporal lobe. (Photo courtesy of: Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine, http://csu-cvmbs.colostate.edu/vdl/Pages-/default.aspx) |

Imaging Results:

On postmortem MRI, there is a large, broad-based mass in the mid aspect of the dorsal left calvarium causing marked rightward deviation and compression of the falx, left lateral ventricle, left frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes. The mass also causes mod-

|

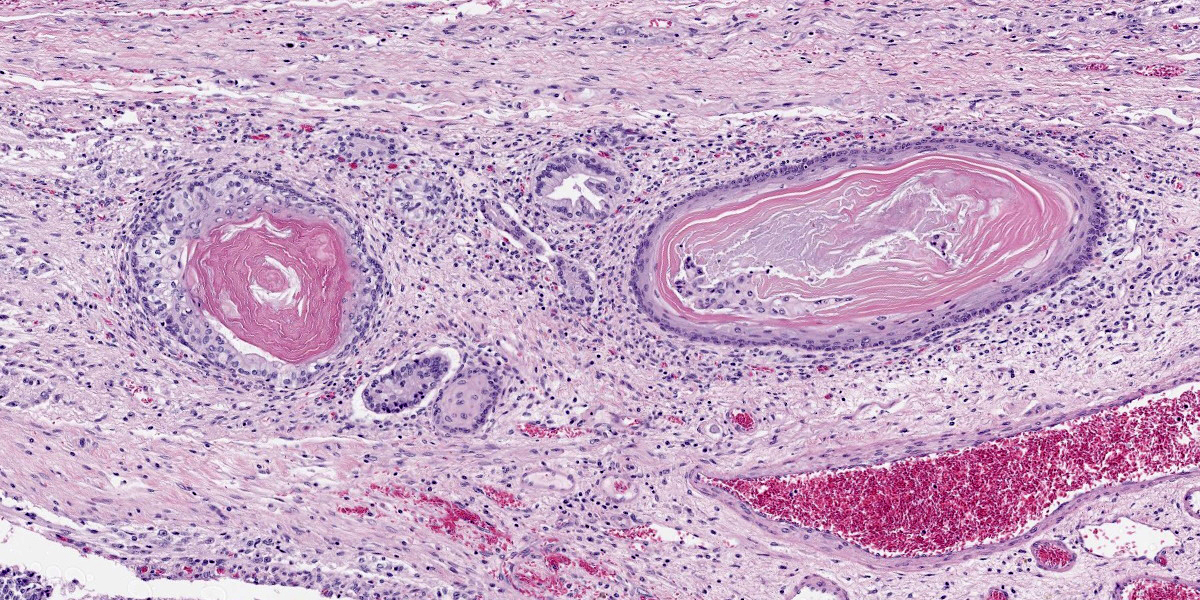

Figure 4-3. Cerebrum, alpaca. A heterogenous, multilobular, infiltrative and cystic mass effaces the neuroparenchyma. (HE, 5X) |

erate dorsal compression of the left mesencephalon.

Microscopic Description:

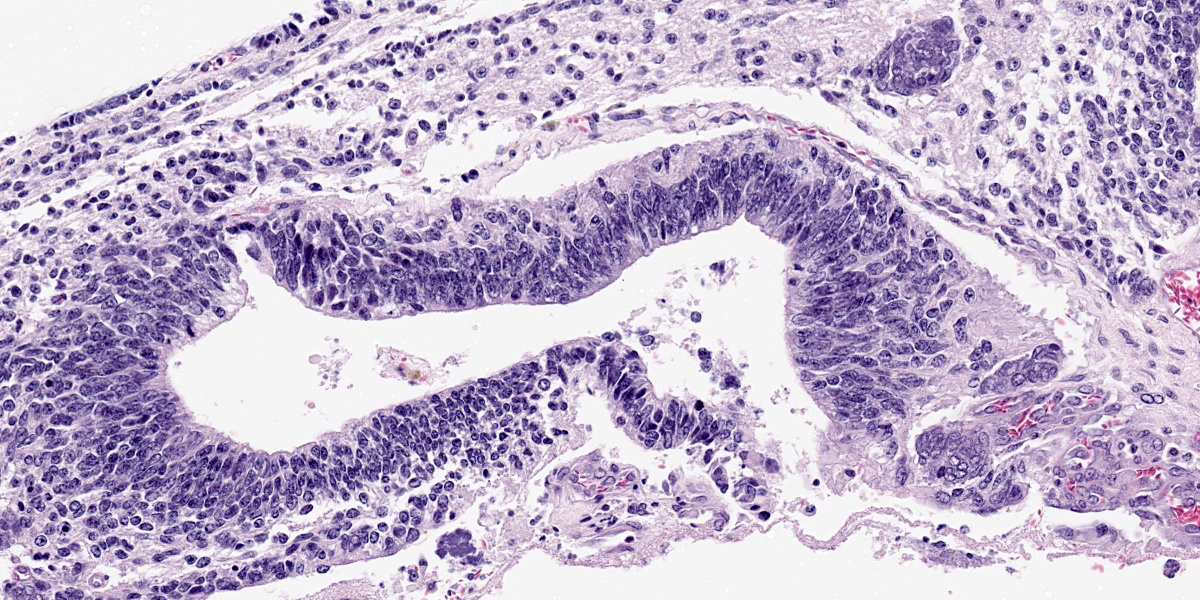

Compressing the cerebrum is a well demarcated, densely cellular, multilobular neoplasm composed of several populations of primitive cells as well as tissue representing all three primordial germ cell lines. Primitive neuroectodermal cells are arranged in dense sheets, as well as pseudorosettes and occasionally rosettes. These primitive cells are often elongate with indistinct cell borders, a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and ovoid to elongate nuclei. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis in this population varies from mild to moderate and mitoses vary based of region. In more mitotically active regions, there are up to 15 mitoses in a single 400x field. Ectodermal components are comprised of well differentiated neurons associated with glial cells and neuropil. Additionally there are numerous cysts filled with lamellated keratin and keratin debris and lined by orderly stratified squamous epithelium. In a single keratin cyst, numerous cross sections of hair shafts are present (not available in all sections provided). Endodermal components are comprised of multifocal regions where neoplastic tissue forms variably sized cysts lined by a single layer of cuboidal to pseudostratified columnar epithelium. The apical surface of this epithelium occasionally has variably distinct, irregular cilia-like projections (respiratory epithelium). Mesodermal elements are comprised of nodules of mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts), as well as bands of smooth muscle adherent to the basal surface of both squamous and respiratory epithelial lined cysts. There is a single focus of well-differentiated cartilage (not present in all sections), as well as infrequent foci where there are individualized to small aggregates of adipocytes. The mitotic rate is low across all well-differentiated cell types. Adjacent normal neuropil is not present in all sections.

|

Figure 4-4. Cerebrum, alpaca. The predominant cell in the neoplasm is a poorly differentiated neuroectodermal cell which is arranged in nests and packets, sheets, streams, and occasional rosettes and pseudorosettes. (HE, 5X) |

Immunohistochemistry for synaptophysin reveals primitive neuroectodermal cells that multifocally exhibit punctate to diffuse cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for synaptophysin. Neoplastic neurons and neuropil also exhibit strong cytoplasmic labeling for synaptophysin. Blood vessels, bands of smooth muscle dissecting between large nodules of

|

Figure 4-5. Cerebrum, alpaca: The predominant and primitive cell type is positive for cytokeratin. (anti-AE1/AE3, 200X) (Photo courtesy of: Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine, http://csu-cvmbs.colostate.-edu/vdl/Pages/default.aspx) |

primitive neuroectodermal cells, and smooth muscle adherent to the basal surface of epi-

thelial lined cysts exhibits strong staining for smooth muscle actin. Several large nodules of primitive neuroectodermal neoplastic cells exhibit irregular, punctate cytoplasmic labeling with cytokeratin. Additionally, epithelium lining cysts exhibit strong cytoplasmic staining for cytokeratin. All neoplastic structures, except epithelial structures that are cytokeratin positive, have strong cytoplasmic staining for vimentin.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Teratoma

Contributor’s Comment:

In human literature, classification of teratomas histologically is divided into three categories: mature, immature, and malignant.6 Mature teratomas are characterized by several types of mature, well-differentiated tissues, and immature teratomas are comprised of poorly differentiated, primitive tissues.6 Both types are classically comprised of tissues from all three germ layers. Histopathology of teratomas is widely varied but distinct in complexity. Diagnosis is made when tissue types from two or more of the germinal layers are present. The three germinal layers and tissues representing each of them are as follows:3,6

- Mesoderm: notochord, musculoskeletal system (including bone and cartilage), muscular layer of stomach and intestine, circulatory and lymphatic systems, reproductive system (excluding germ cells), dermis of skin, adrenal cortex;

- Endoderm: epithelial linings (digestive tract, respiratory system, urinary system), liver, pancreas, epithelial component of the thymus, thyroid and parathyroid; and

- Ectoderm: epidermis of skin, sweat glands, hair follicles, epithelial lining of mouth and anus, cornea and lens, nervous system, adrenal medulla, tooth enamel, epithelium of pineal and pituitary glands.

|

Figure 4-6. Cerebrum, alpaca. Ectodermal structures recapitulating hair follicles are scattered throughout the mass. (HE, 147X) |

Teratocarcinomas (malignant variants) are, in both human and veterinary literature, very rare. These tumors contain somatic-type neoplastic components and, in people, the most commonly seen are rhabdomyosarcomas and

|

Figure 4-7. Cerebrum, alpaca. Pseudostratified epithelium recapitulates endodermal elements of gut or respiratory epithelium. (HE, 260X) |

undifferentiated sarcomas.6 Ultimately, a diagnosis of immature teratoma was given

based on the high proportion of primitive neuroectodermal components.

In general, teratomas are benign tumors that most often arise in the gonads. In rare circumstances, however, they arise in extragonadal locations, including within the calvarium, and cause significant clinical disease secondary to local mass effect. A handful of reports exist documenting teratomas within the cranium in a variety of veterinary species including a rabbit, kitten, rat, dog, kestrel and an alpaca.1,2,4,5,11 Other reports of nongonadal sites include adrenal teratomas in ferrets, a renal teratoma in a llama and retrobulbar teratomas in a cat, kestrel and great blue heron.5,9,12,13,14

Contributing Institution:

Colorado State University

College of Veterinary Medicine

https://vetmedbiosci.colostate.edu/vdl/

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Teratoma.

JPC Comment:

With a name derived from the Greek words “teras,” meaning monster, and “onkoma” meaning swelling, teratomas have been objects of fascination and speculation for centuries, likely due to their startling propensity to produce a disorganized jumble of anatomic structures such as hair, teeth, and eyes.10 Historically, teratomas have often been interpreted as evidence of Satanic possession or all manner of salacious activities, and all of this attention had an unexpected benefit: research surrounding this fascinating entity led fairly directly to the discovery of embryonic stem cells in the late twentieth century.7

As the contributor details, teratomas are distinguished from other tumors by the presence of tissue from multiple embryonic germ layers. This developmental plasticity is shared with embryonic stem cells which are defined by their pluripotency and capacity for self-renewal. In the last thirty years, tremendous strides have been made in developing pluripotent and induced pluripotent human stem cell lines which hold the tantalizing possibility of revolutionizing regenerative and transplant medicine.

A definitional concern when developing stem cell lines is how to test for pluripotency. This can be done by a variety of in vitro and in vivo measures; however, the gold standard method to confirm developmental pluripotency is the in vivo “teratoma assay.”8 The assay involves injecting presumptively pluripotent stem cells into immunodeficient mice, where, if truly pluripotent, they develop teratomas. These tumors are allowed to grow and are then removed and analyzed histologically to ensure that the tumor produced cell populations from all three developmental layers.8 The teratoma assay also allows pathologists to assess whether the resulting mass contains malignant elements which may increase the incidence of stem cell-induced malignancies, a current roadblock to more widespread implementation of clinical trials for stem cell therapies.8 While ethical and humane questions surround the assay and alternatives to its use are being actively sought, the once- maligned teratoma has, for now, found new work as a cornerstone of the embryonic stem cell revolution.

References:

- Bishop L. Intracranial teratoma in a domestic rabbit. Vet Pathol. 1978; 15(4): 525-530.

- Chénier S, Quesnel A, Girard C. Intracranial teratoma and dermoid cyst in a kitten. Jour Vet Diag Invest. 1998;10(4): 381-384.

- Higgins RJ, Bollen AW, Dickinson PJ, Siso?-Llonch S. Tumors of the Nervous System. In Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in domestic animals. 5th ed. Wiley Blackwell; 2017: 834-891.

- Hill FI, Mirams CH. Intracranial teratoma in an alpaca (Vicugna pacos) in New Zealand. Vet Rec. 2008;162(6):188-189.

- López RM, Múrcia DB. First description of malignant retrobulbar and intracranial teratoma in a lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni). Avian Pathol. 2008;37(4): 413? 414.

- Louis DN, Ohaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. Germ Cell Tumors. In WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016:285-291.

- Maehle AH. Ambiguous cells: the emergence of the stem cell concept in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Notes Rec R Soc Lond. 2011 Dec 20;65 (4):359-78.

- Montilla-Rojo J, Bialecka M, Wever KE, et al. Teratoma assay for testing pluripotency and malignancy of stem cells: insufficient reporting and uptake of animal-free models-a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4): 3879.

- Patel JH, Kosheluk C, Nation PN. Renal teratoma in a llama. Can Vet J. 2004; 45(11):938?940.

- Raup C. “Teratomas.” Embryo Project Encylopedia. https://embryo.asu.edu/han dle /10776/1919.

- Reindel J, Bobrowski W, Gough A, Anderson J. Malignant intracranial teratoma in a juvenile Wistar rat. Vet Pathol. 1996;33(4):462?465.

- Schelling, SH. Retrobulbar teratoma in a great blue heron (Ardea Herodias). Jour Vet Diag Invest. 1994;6(4):514–516.

- Williams BH, Yantis LD, Craig SL, Geske RS, Li X, Nye R. Adrenal teratoma in four domestic ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Vet Pathol. 2001;38(3): 328–331.

- Wray JD, Doust RT, McConnell F, Dennis RT, Blunden AS. Retrobulbar teratoma causing exophthalmos in a cat. J Feline Med Surg. 2008;10(2):175?180.