Signalment:

28-year-old, female, Nilgiri langur, (Trachypithecus johnii).An adult female

captive born Nilgiri langur (

Trachypithecus johnii) from a zoological

garden in Central Europe developed an edematous swelling of the left thigh,

which persisted for several months and was associated with periods of a

decreased general condition, depression, and anorexia. Sonographic examination

of the thorax and abdomen revealed cardiomegaly as well as poor demarcation and

cloudy appearance of the liver. The animal was finally euthanized due to a poor

general condition, anorexia, and therapeutic resistance.

Gross Description:

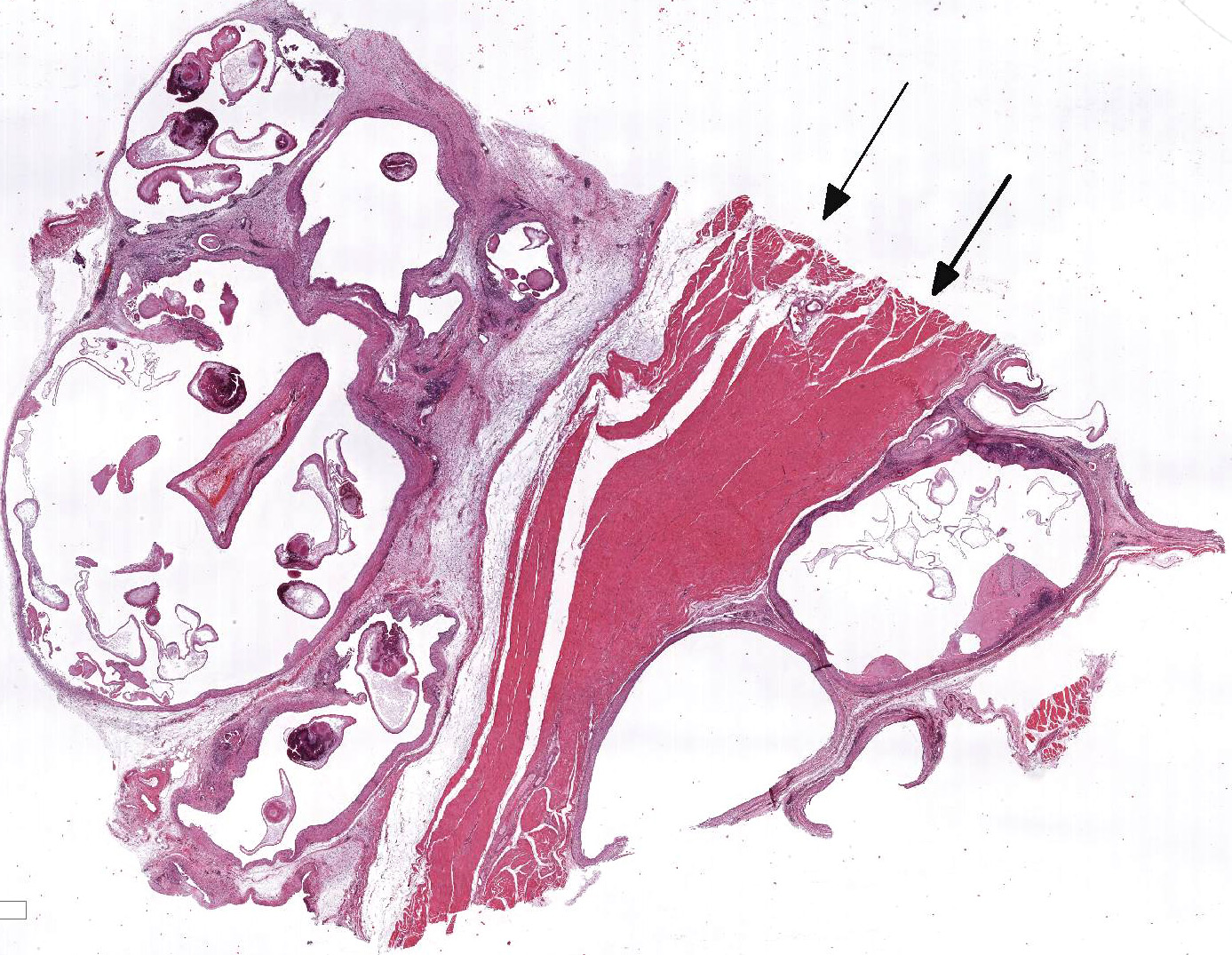

At necropsy, the

animal was cachectic. The skeletal muscle of the left thigh was severely

atrophic and replaced by fluctuant multilocular cysts containing numerous sand

grain sized whitish structures. The left caudal lung lobe revealed a focal

circumscribed area of atelectasis.

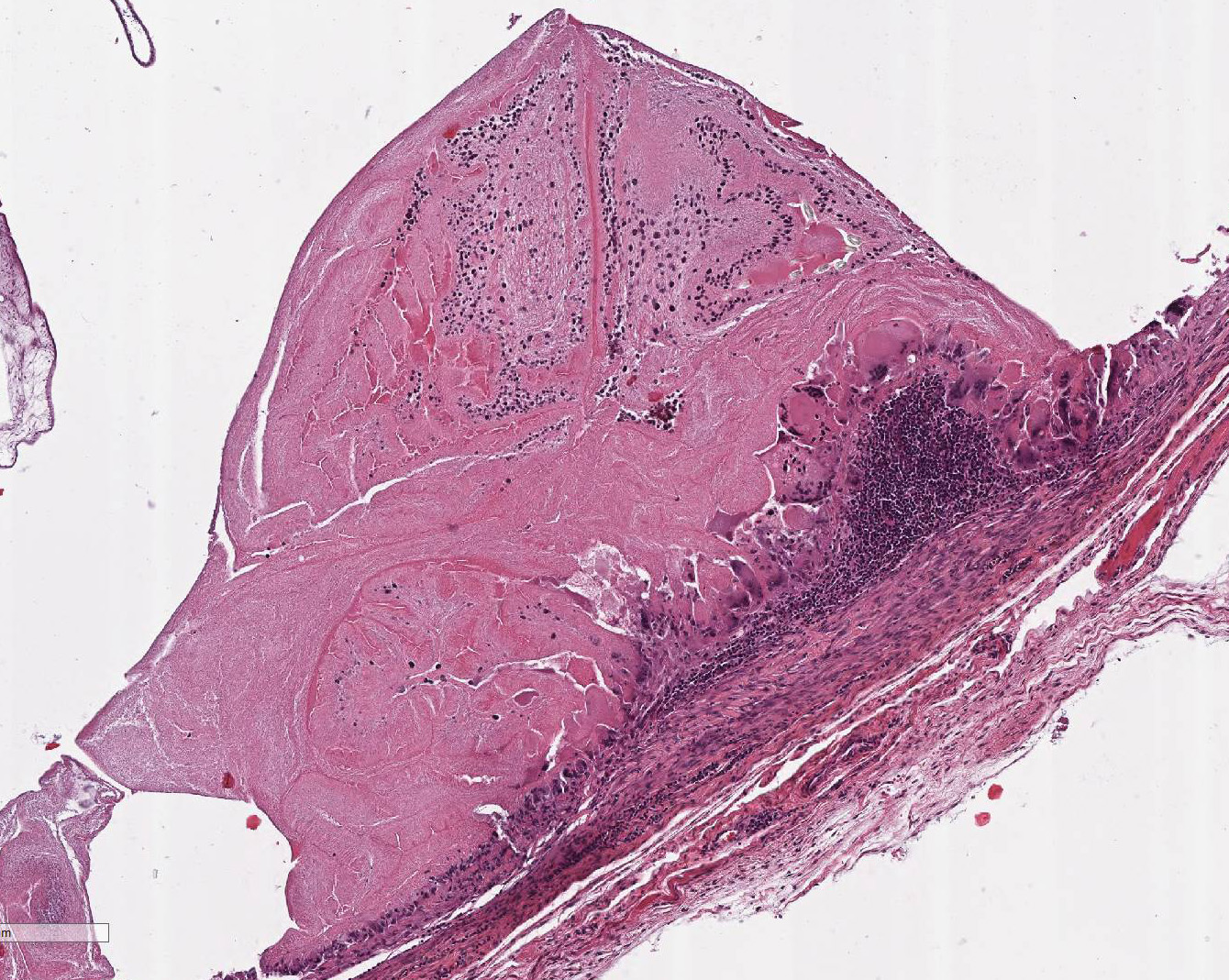

Histopathologic Description:

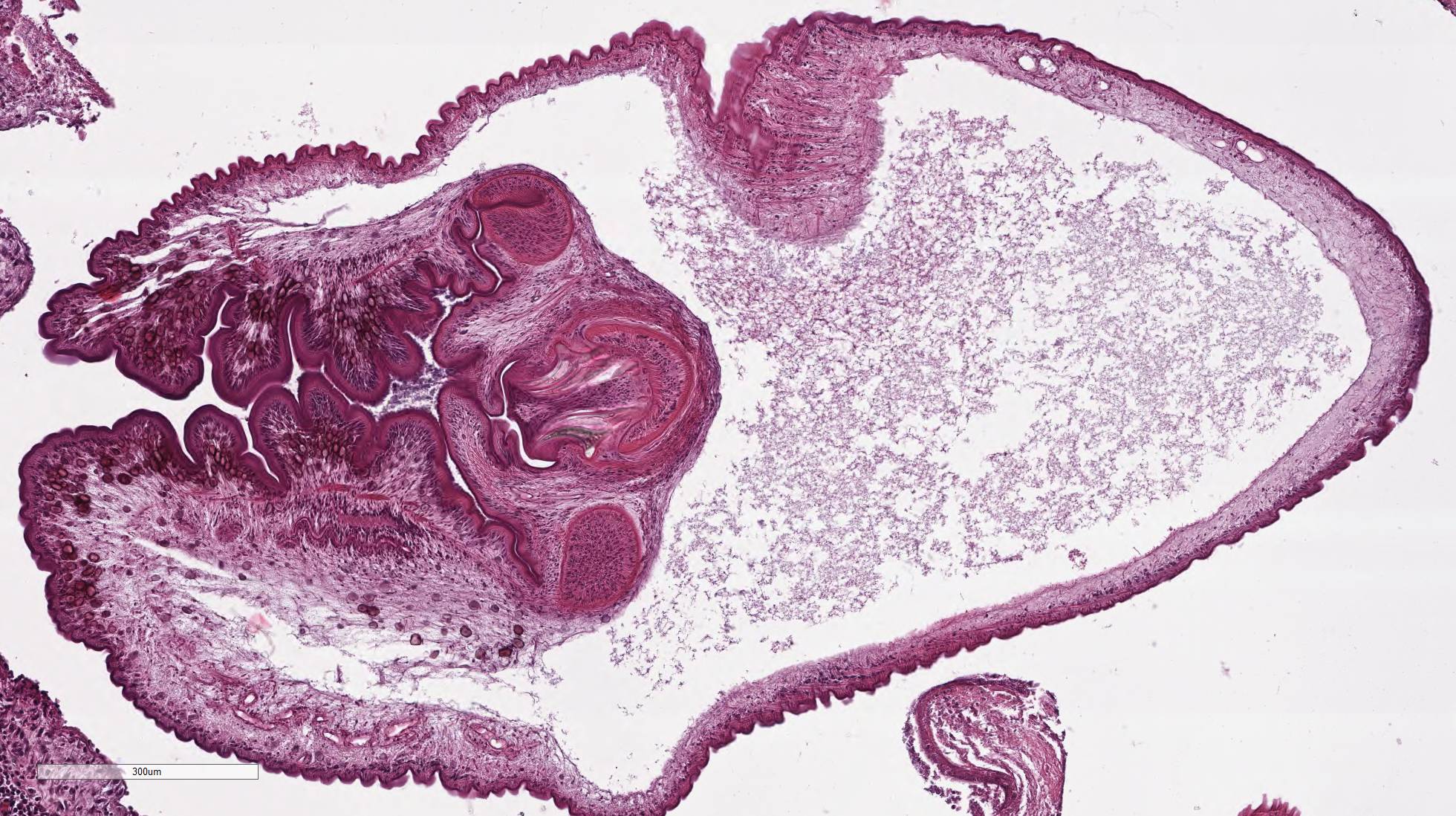

Within the skeletal muscle of the left

thigh are multifocal extensive areas of fibrous connective tissue bearing

multiple cystic structures with numerous larval cestodes (cysticerci). Cysts

are surrounded by thick fibrous capsules that are multifocally infiltrated by

plasma cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils. The inflammatory cells

extend into the adjacent fibrous granulation tissue between muscle fibers that

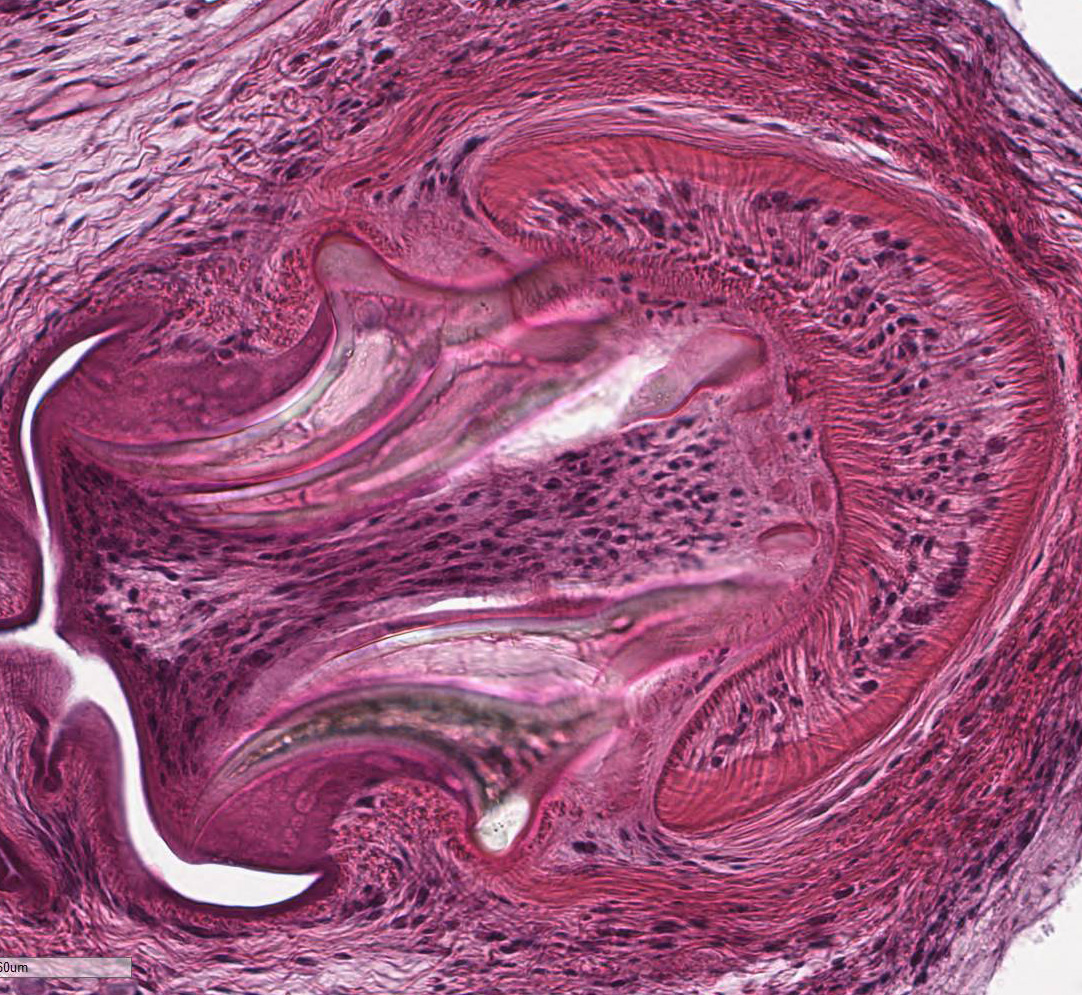

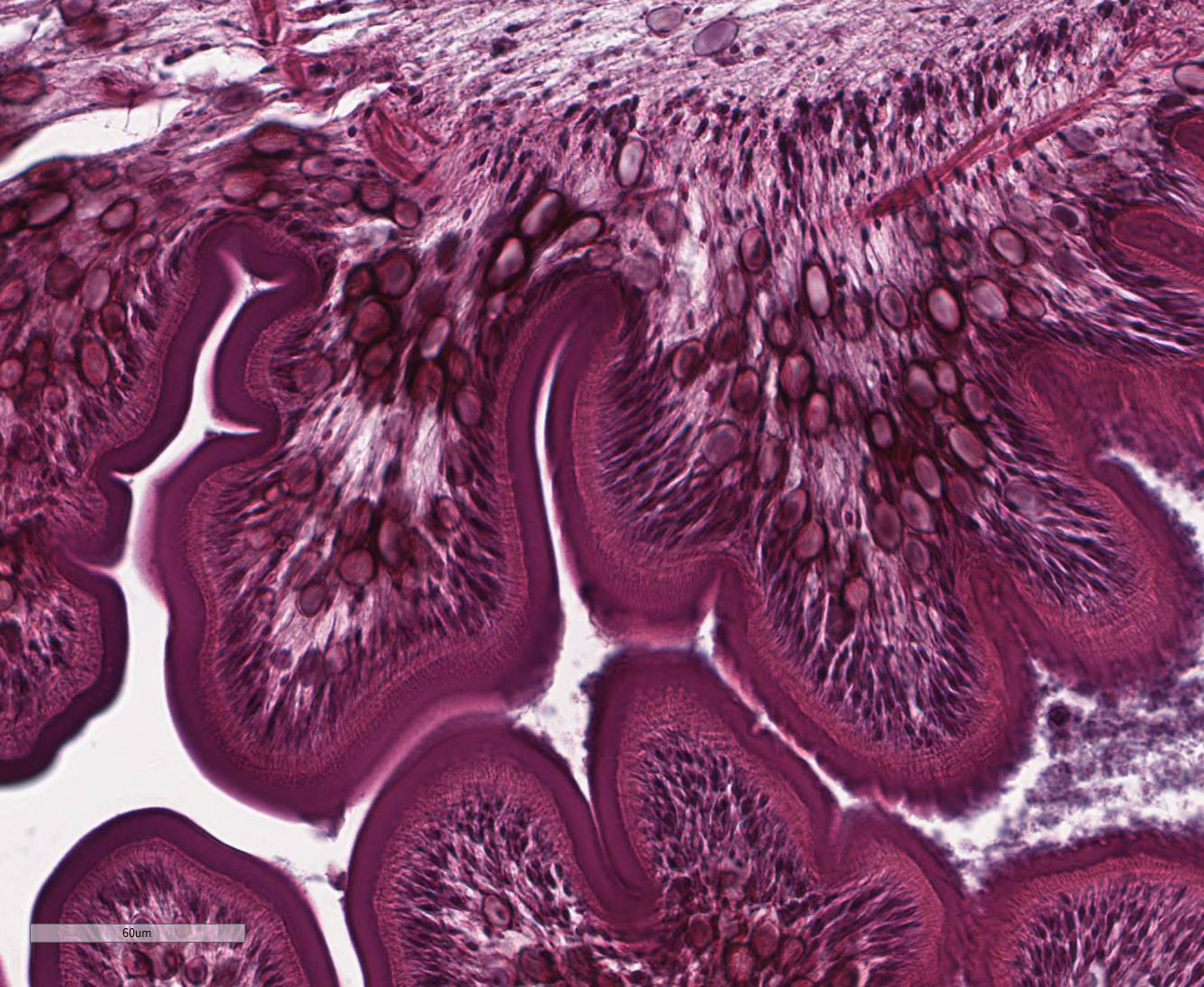

contains few multinucleated giant cells. Cysticerci are characterized by a 4 µm

thick, eosinophilic tegument, a fibrillar, eosinophilic parenchyma, numerous 5

µm diameter, basophilic, calcareous corpuscles, and an invaginated scolex with

muscular suckers and hooks.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Skeletal muscle: Myositis, chronic, gran-ulomatous

and eosinophilic, multifocal, severe, with intralesional cysticerci, Nilgiri

langur (

Trachypithecus johnii), non-human primate.

Lab Results:

PCR

analysis of muscular metacestode tissue identified

Cysticercus longicollis,

the larval stage of

Taenia crassiceps,

as the etiologic agent.

Condition:

Cysticercus longicollis, langur

Contributor Comment:

Non-human

primates might act as aberrant hosts for a number of cestode species after oral

infection and larval development in extra-intestinal locations.

2 Taenia

crassiceps is a cestode parasite of the Northern hemisphere, whose life

cycle includes canids as definitive hosts, most commonly the red fox (

Vulpes

vulpes) in Europe and the Artic fox (

Alopex lagopus) as well as the

red fox in North America.

6 Natural infection by

T. crassiceps

has also been reported in wolves (

Canis lupus)

5 and coyotes (

Canis

latrans)

13 in North America as well as in wild cats (

Felis

silvestris)

12 and domestic dogs in Germany.

3 Several

rodent species and rabbits serve as intermediate hosts for the metacestode

larval stage of the parasite,

Cysticerus (

C.)

longicollis.

However, the common vole (

Microtus arvalis) is the predominant

intermediate host in Europe.

1 Sporadic cases of clinical

cysticercosis caused by

T. crassiceps have been reported in

humans and domestic animals such as dogs and cats, many of them in immuno-compromised

individuals.

8,9,16 Infections by

T. crassiceps may be

particularly serious due to their proliferative nature. In contrast to

cysticercosis associated with other

Taenia species,

T. crassiceps

is able to proliferate by exogenous and endogenous budding. Exogenous budding

may produce 1-6 daughter cysticerci at the abscolex pole of the maternal cyst.

Daughter cysticerci may bud off or remain attached by a stalk, form a scolex of

their own, and bud again. Endogenous budding occurs less commonly and is seen

in larger, older cysticerci. Such reproductive capability may result in

extensive infections, most frequently involving the subcutis and pleural and

peritoneal cavities. In humans, there are occasional reports about intraocular

mani-festations of cysticercosis.

4

In non-human

primates, there are documented cases of

T. crassiceps cysticercosis in a

black lemur (

Eulemur macaco macaco)

4 and in a ring-tailed

lemur (

Lemur catta)

10, both of them being prosimian species.

T.

crassiceps cysti-cercosis in an Old World monkey species like the Nilgiri

langur has not been reported before. Interestingly, in the langur, metacestode

tissue was not limited to the skeletal muscle, but could also be observed in

the left caudal lung lobe, reflecting the proliferative and invasive nature of

this parasite.

Other

Taenia

species causing cysticercosis in non-human primates include

Taenia solium,

Taenia crocutae,

Taenia hydatigena, and

Taenia martis.

2,14

However, infections with the larval cestodes mainly occur in Old World monkeys

and apes, while reports of taeniid cysticercosis in New World monkeys and

prosimians are sparse.

Studies

on the immune response elicited by

T. crassiceps and its antigens in

human and mice cells suggest a strong capacity of this parasite to induce a

chronic Th2-type response that is primarily characterized by high levels of Th2

cytokines, a low proliferative response in lymphocytic cells, an immature and

LPS-tolerogenic profile in dendritic cells, recruitment of myeloid-derived

suppressor cells, and by activated macrophages.

11

JPC Diagnosis:

Skeletal muscle: Cysticerci, multiple, with mild chronic granulo-matous

inflammation, Nilgiri langur (

Trachypithecus johnii).

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides a striking example of multiple

intramuscular cysticerci containing cross sections of taeniid metacestodes, the

larval form of cestode tapeworms. The class

Cestoda has two orders of

veterinary importance. The first is

Pseudophyllidea, comprised of

Diphyllobothrium

sp. and

Spirometra sp.

15 These parasites grow into extremely

large adults, up to 15 meters in humans, lack suckers, and require two

intermediate hosts, typically an aquatic copepod and fish. In contrast, the

order

Cyclophyllidae, which contains

Taeniidae,

Mesocestoididae,

Dipylidiidae,

Ano-plocephalidae, and

Hymenolepididae,

require only one intermediate host, usually a land mammal or arthropod.

15

Adult cestodes are normally present in the

intestine, hepatic ducts, and/or pancreas of the final definitive host while

the larval forms are present within the tissue or body cavities of intermediate

hosts. Adult cestodes are broken into segments, called proglottids, which

contain both female and male reproductive organs. Cyclophyllidae have four

anterior suckers present in both larval and adult cestodes and birefringent

armed hooks, depending on the species. The four anterior suckers may not all be

visible histologically due to varying planes of section.7,15

While adult tapeworms are usually of minor

significance in their carnivorous definitive hosts, the larval form can migrate

into various tissue and cause significant pathology in intermediate or

paratenic hosts. Conference participants discussed the four different forms of

larval cestodes in tissue section. These include cysticercus, present in this

case, strobilocercus, coenurus, and the hydatid cyst.7,15 The

cysticercus is thin walled, fluid filled, and contains a single larva with one

inverted scolex and four suckers. The strobilocercus is later in development

and contains an evaginated and elongated scolex and develops multiple segments,

similar to the adult cestode. Coenurus is similar to cysticercus but contains

more than one scolex, all of which can develop into an adult in the definitive

host. Hydatid cysts, typical of the genus Echinococcus sp., have a

bladder with large numbers of small protoscolicies grouped into clusters called brood capsules.7,15

The inflammatory response in this case is mild and composed

of a mixed population of histiocytes, multinucleated giant cell macrophages,

lymphocytes, and plasma cells with mild atrophy of the adjacent skeletal muscle

bundles. The glycoprotein-rich wall of the cysticerci provokes little to no

host reaction when intact; however, rupture of the cysticerci results in a

severe granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and mineralization.15

Additionally, Cysticercus longicollis, the larval form of Taenia

crassiceps present in this case, undergoes both endogenous and exogenous

budding of the cysticerci leading to severe and disseminated infection.4

References:

1. Bröjer

CM, Peregrine AS, Barker IK, et al. Cerebral cysticercosis in a woodchuck (Marmota

monax). J Wildl Dis. 2002;38:621-624.

2. Brunet

J, Pesson B, Chermette R, et al. First case of peritoneal cysticercosis

in a non-human primate host (Macaca tonkeana) due to Taenia martis.

Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:422.

3. Dyachenko

V, Pantchev N, Gawlowska S, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis infections

in domestic dogs and cats from Germany and other European countries. Vet Parasitol.

2008;157:244-253.

4. Dyer

NW, Greve JH. Demar M, et al. Severe Cysticercus longicollis

cysticercosis in a black lemur (Eulemur macaco macaco). J Vet

Diagn Invest. 1998;10:362-364.

5. Freeman

RS. Cestodes of wolves, coyotes and coyote-dog hybrids in Ontario. Can J

Zool. 1961;39:527-532.

6. Freeman

RS. Studies on the biology of Taenia crassiceps (Zeder, 1800) Rudolphi,

1810 (Cestoda). Can J Zool. 1962;40:969-990.

7. Gardiner CH and Poynton SL: Morphologic

characteristics of cestodes in tissue section. In: An atlas of metazoan parasites in

animal tissues: American Registry of Pathology, Washington, D.C. 1999,

50-55.

8. Hoberg

EP, Ebinger W, Render JA. Fatal cysticercosis by Taenia crassiceps (Cyclophyllidea:

Taeniidae) in a presumed immunocompromised canine host. J Parasitol.

1999;85:1174-1178.

9. Lescano

AG, Zunt J. Other cestodes: sparganosis, coenurosis and Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis.

Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;114:335-345.

10. Luzón

M, de la Fuente-López C, Martínez-Nevado E, et al. Taenia

crassiceps cysticercosis in a ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). Zoo Wildl Med.

2010;41:327-330.

11. Peón

AN, Espinoza-Jiménez A, Terrazas LI. Immunoregulation by Taenia crassiceps

and its antigens. Biomed Res Internat. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/498583.

12. Schuster

R, Heidecke D, Schierhorn K. Contribution to the parasite fauna of local hosts.

On the endoparasitic fauna of Felis silvestris. Appl. Parasitol.

1993;34:113-120.

13. Seesee

FM, Sterner MC, Worley DE. Helminths of the coyote (Canis latrans Say)

in Montana. J Wildl Dis. 1983;19:54-55.

14. Strait

K, Else JG, Eberhard ML. Parasitic diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR,

Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. 2nd ed. Nonhuman

primates in biomedical research: diseases. San Diego,

USA: Academic Press; 2012:197-298.

15. Uzal

FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG ed.

In: Jubb Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol

2. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:221-225.

16. Wüschmann

A, Garlie V, Averbeck G, et al. Cerebral cysticercosis by Taenia crassiceps

in a domestic cat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2003;15:484-488.