Signalment:

Gross Description:

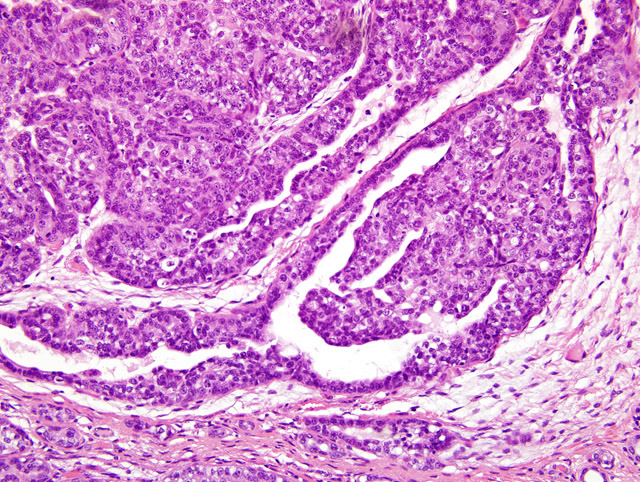

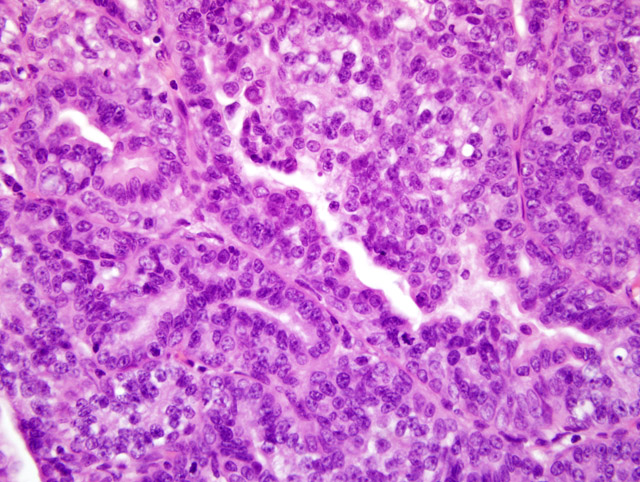

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Differentiation between DCIS and LCIS is crucial in humans because management strategies differ greatly between the two types.(7) In humans, estrogens have been hypothesized as contributing to the formation of mammary tumors. Estrogen stimulates the mitosis of breast epithelial cells regardless of the gender and can enhance unregulated growth of mammary tissue.(1) This particular case is interesting because it represents a mammary gland carcinoma in a male, which has been rarely reported. One report gives an incidence rate of 1.1% in a long term study of untreated animals.(8) This rate is similar to that seen in men, accounting for 0.8% of all the cases of mammary carcinoma. Most mammary carcinoma in human males is ductal in origin with the majority being invasive. Mammary gland carcinoma in men has been reported to be linked to testicular abnormalities, Klinefelter syndrome, familial history of breast cancer, infertility and breast discharge. They tend to be estrogen and progesterone receptor positive.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

During the post conference, part of the discussion focused on general features distinguishing benign from malignant tumors. These features include pleomorphism, nuclear morphology, appearance of mitotic figures and overall mitotic rate, polarity, and invasiveness.

In malignant tumors, both cells and nuclei generally display greater variation in size and shape than do their benign counterparts. Cells can be much larger or smaller than adjacent cells, with similar variation in nuclear size. These changes are referred to as anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, respectively. In malignant tumors, nuclei often contain an abundance of DNA and stain much darker (hyperchromatic). The nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio can also approach a 1:1 ratio from the normal 1:4 to 1:6 ratio. Mitotic figures are more abundant in malignant tumors than in benign tumors. Often, malignant tumors also have bizarre mitotic figures forming abnormal shapes and patterns that do not resemble the normal mitotic rearrangement of chromosomes. These cells often produce multipolar spindles, which can create a highly unusual cellular appearance in relation to neighboring cells. Malignant tumors are generally faster growing neoplasms with growth occurring in a more disorganized, haphazard fashion (often referred to as loss of polarity). Malignant tumors also tend to invade surrounding tissue and metastasize to regional lymph nodes and other organ systems, whereas benign tumors stay in the location of origin. There can be a wide range of morphologic appearances within tumors depending on the specific type of tumor and the tissue involved, so these guidelines are meant as a general rule and are subject to vary from one type of neoplasm to the next. (4)

Mammary gland lesions have been reported in numerous lab animals and domestic species, and a few of the more common of these were discussed during the post-conference session. A chart listing the species discussed during this session and the changes in each species is included below.

| Species | Mammary change | Cause |

| Rat | Fibroadenoma (S-D strain) | Increase in prolactin |

| Rabbit | Mammary dysplasia | Pituitary tumor |

| Mouse | FVB/N mice hyperplasia of mammary glands Mammary tumors | Proliferation of prolactin secreting cells in pars distalis Mammary tumor viruses (MMTVs) |

| Cat | Fibroepithelial hyperplasia | Progesterone administration (Ovaban other iatrogenic hormones) |

| Canine | Gynecomastia | Sertoli cell tumor |

References:

2. Foster RA, Ladd PW: Male genital system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., pp. 596-597. Elsevier, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2007

3. Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN: Breast cancer in men. Annals of Internal Medicine 137:678-687. Primatology 2001; 30:121126

4. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N: Neoplasia. In: Robins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, ed. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, 7th ed., pp. 272-276. Elsevier, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2005

5. Percy DH, Barthold SW: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 3rd ed., pp.116-117, 170-171, 306. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa, 2007

6. Moll R, Mitze M, Frixen UH: Differential loss of E-cadherin expression in infiltrating ductal and lobular breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol 143:173142, 1993

7. Schnitt SJ, Morrow M: Lobular carcinoma in situ: current concepts and controversies. Semin Diagn Pathol 16:20923, 1999

8. Wood CE, Usborne A, Tarara R, Starost MF: Hyperplastic and neoplastic lesions of the mammary gland in macaques. Vet Pathol 43:471483, 2006