CASE 1: 1316/18 (4136811-00)

Signalment:

12 year old, female, worm-blooded, Equus caballus, horse

History:

A 12-year-old Warmblood mare was presented to the Surgery Clinic with a 5 month history of epistaxis and facial swelling. At admission, a swollen area size 5 x 3 cm proximal of crista facialis was obvious together with epiphora and blepharospasm on the right eye. A strong stertor could be heard during rest. Sinus centesis revealed the presence of a large volume of red-yellow, viscous fluid.

Radiography noted osteolytic processes with complete shading of maxillary and frontal sinuses and mild deviation of the nasal septum. Endoscopic findings included constriction of ventral nasal meatus of the affected side and the presence of reddish yellow mass within sinuses that started to bleed. A suspected diagnosis of sinus cysts was established.

Standing surgery was attempted but due to mare temper, the surgery had to be performed in general anesthesia. A frontonasal flap was performed and a cavity with a red-yellow, smooth surface was observed. The cavity was stretching through all ipsilateral sinuses and it was not possible to differentiate between each sinus compartment. During the surgery the owner was contacted and due to poor prognosis, the animal was euthanized and submitted for necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

Necropsy just revealed the size of the cavity that stretched through the nasal cavity and all ipsilateral sinuses at the right side. Nasal conchae were completely destroyed. The cavity was filled with dark red to yellow, friable mass covered with fresh coagulated blood on the surface (the mass was partially removed by the surgery so we could not estimate the real size).

Laboratory results:

None.

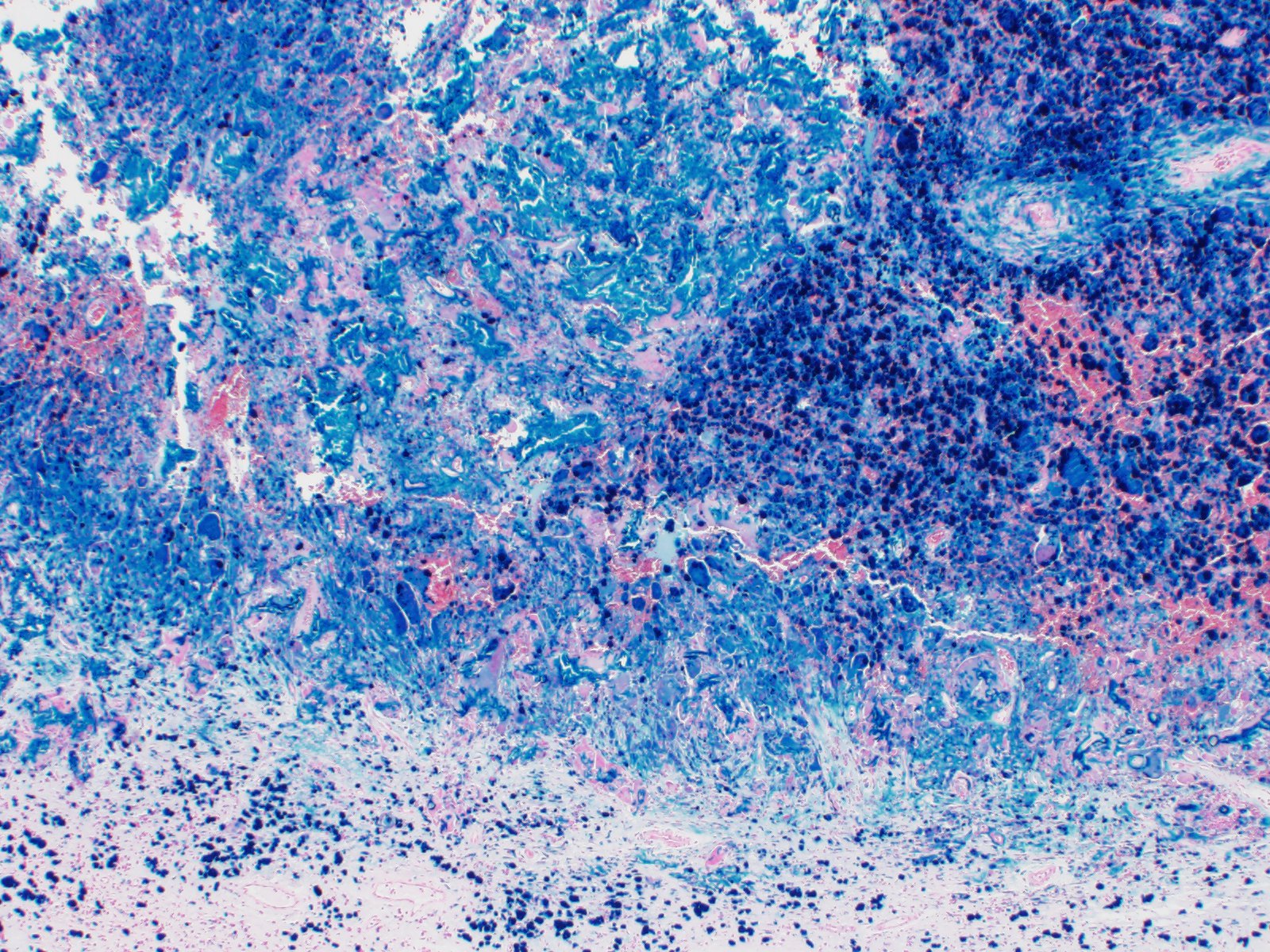

Microscopic description:

Respiratory epithelium (paranasal sinus); at one side the section is covered by columnar or cuboidal ciliated epithelium that is occasionally flattened or missing. Subepithelial connective tissue is edematous with dilated lymphatics and infiltrated with scant to moderate lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic infiltrate. An edematous fibrous layer progress to the mass composed of numerous macrophages and multinucleated giant cells, moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, admixed with hemorrhage, fibrin, and multifocal increased numbers of small to medium caliber vessels (neovascularization). Many giant cells and macrophages contain abundant golden-yellow granular pigment (hemosiderin/hematoidin) and there are large, extracellular globular aggregates of yellow hematoidin pigment (ceroid sequins). There are multifocal small aggregates of deeply basophilic, finely granular pigment (mineralization) that mostly accumulate in the basement membranes of capillaries.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Paranasal sinus mucosa: granulomatous inflammation with hemorrhage, hemosiderosis, hematoidin and mineralization.

Condition: Progressive ethmoid hematoma

Contributor's comment:

The paranasal sinus system of horses is complex, comprising six pairs of sinuses: the frontal sinus, the conchal sinuses (dorsal and ventral), the maxillary sinus, and the sphenopalatine sinus. Disease processes that can develop in the sinuses include ethmoid hematomas, cysts, neoplasia, and bacterial and fungal infections. Horses that develop paranasal sinus disease vary widely in age. Because of the anatomic location of the paranasal sinuses and associated chronic conditions that affect many patients, many disease processes involving the paranasal sinuses require surgical correction for a favorable prognosis. Fungal and neoplastic processes have a less favorable prognosis than bacterial and other processes.12

A progressive ethmoid hematoma (PEH) is a nonneoplastic, progressive, and locally destructive growth in the paranasal sinuses that resembles a tumor. Even though its etiology is unknown, it is hypothesized that PEH originates in the submucosa of the ethmoid labyrinths resulting from repeated episodes of hemorrhage which lead to formation of an angiomatous-like mass, covered by the respiratory epithelium. The mass grows slowly but progressively, protruding ventrocaudally into the ipsilateral ethmoidal meatus and then into the nasopharynx, contralateral nasal cavity and adjacent paranasal sinuses. Clinical signs appear when the mass reaches a size big enough to induce severe local destructive effects, which are characterized by intermittent monolateral epistaxis, particularly during exercise.2,4,6 Histologically, the lesion is covered by pseudostratified columnar epithelium containing mucus cells, but focal ulceration, secondary infection, or focal squamous metaplasia of the mucosa may occur. A submucosal fibrous tissue pseudocapsule surrounds the central mass of hemorrhage, and there can be areas of loose vascular channels and sinuses lined by plump spindle-shaped cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Foci of recent hemorrhages are accompanied by large macrophages and multinucleated foreign body-type giant cells that usually contain large amounts of hemosiderin. The organization of the hemorrhage proceeds by the development of capillaries and fibrous tissue. Both the blood vessels, some of which may be thrombosed, and the collagen fibers, have calcareous deposits on them, along with globin-derived pigments and hemosiderin.6

In the presented case, a sinus cyst with repeated chronic hemorrhage cannot be excluded. Sinus cysts are extensive lesions also of unknown etiology that are single or loculated, fluid-filled cavities with an epithelial lining. They develop in the maxillary sinuses and ventral conchae but can extend into the frontal sinus and nasal cavity. Abnormal development of embryonic germ tissue and cystic development caused by repeated submucosal hemorrhage have been proposed as etiologic factors.8,13,14 It is characterized by firm facial swellings and nasal airflow obstruction.4 Histologic findings in sinus cysts include granulation tissue, neovascularization, ulceration, hemorrhage, fibroplasia, inflammatory cell infiltration, mineralization, and bony trabeculation in the cyst wall.12,13 Lane et al. (1987) suggested an association of sinus cyst with progressive ethmoidal hematoma based on the histological evidence of repeated hemorrhages within cysts wall and PEH. However, in one other study there was sufficient evidence to confirm such an association.12 In this study, recent and older hemorrhages were also observed in some cases of chronic sinusitis. Additionally, in this study, the double epithelial lining found in most sinus cysts was not found in any of the (solid) PEH. Moreover, unlike many sinus cysts, PEH sections examined in this study never contained bony spicules. Thinning and remodeling of the overlying bones was rare with PEH in contrast to sinus cysts, where this feature (and subsequent gross facial swelling) was common, indicating further significant differences in the nature of these lesions.12 Taking into consideration all of the above, in the presented case, macroscopic findings of facial swelling cannot exclude sinus cyst as underlying disease, but the presence of large hemorrhagic mass and histologic findings are more consistent with PEH.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

University of Zagreb

Heinzelova 55

10000 Zagreb

Croatia

JPC diagnosis:

Nasal mucosa: Rhinitis (sinusitis acceptable), granulomatous, chronic, focally extensive, severe, with acute and subacute hemorrhage, hemosiderosis, and hematoidin deposition.

JPC comment:

Progressive ethmoid hematoma (PEH) usually occurs in older horses, not dissimilar to this case, and is more common in Thoroughbred, Arabian, and warmblood horses. Growth is progressive and can continue to grow until it extends to the external nares.1

While survey radiography can be useful in identifying a sinus mass, endoscopy of the ethmoid conchae is required to confirm a diagnosis of PEH, with CT being the preferred diagnostic imaging modality. While they can arise unilaterally, approximately 30-50% of affected horses are affected bilaterally. There are several interventions to treat PEH, but regardless of treatment choice, PEH recurs in 17-50% of cases within months to years following treatment.11

Other species also develop non-neoplastic proliferative sinus lesions, including the cat and dog. Feline mesenchymal nasal hamartoma is histologically distinct from the nasopharyngeal polyp and is most often composed of woven bone mixed with proliferating fibrous to myxomatous stroma and erythrocyte filled cavities, with a respiratory epithelial lining.5 Both respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma (REAH)9 and chondo-osseous respiratory epithelial adentomatoid hamartoma (COREAH) have been reported in the dog and are histologically similar to their human counterparts.3,10 REAH is composed of a proliferation of glandular spaces lined by respiratory epithelium, overlying a proliferative spindle cell background, with COREAH having an additional chondroid or osseous component.7 These described lesions are currently considered hamartomas, are not invasive, but may cause compression necrosis of adjacent tissues.

The moderator reiterated that this condition has an unknown etiology but is potentially associated with chronic inflammation. During the conference, definitional differences between erosion and ulceration were debated. Erosion is typically described as a loss of mucosa without compromise of the underlying basement membrane. Ulceration has loss of mucosal epithelium and a break in the basement membrane. In human literature, their definition of ulceration requires break through the muscularis mucosa layer, which is not seen in this case.

Also, of note for this entity, the deposits of hematoidin are commonly referred to as "ceroid sequins", though no part of the material is derived from ceroid. Ceroid is a material similar to lipofuscin, associated with peroxidation of fat deposits, and is also yellow. In this case, it is very likely hematoidin and not ceroid, in the context of chronic and acute hemorrhage, and extensive hemosiderin.

References:

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol. 2, 6th Ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2016:477.

- Conti MB, Marchesi MC, Rueca F et al. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive ethmoidal haematoma (PEH) in horses. Vet Res Commun. 2003;27(1):739-743.

- Daniel A, Wong E, Ho J, Singh N. Chondro-Osseous Respiratory Epithelial Adenomatoid Hamartoma (COREAH): Case Report and Literature Review. Case Reports in Otolaryngology. 2019; Article ID 5247091.

- Dixon PM, Parkin TD, Collins N et al. Historical and clinical features of 200 cases of equine sinus disease. Vet Rec. 2011;169: 439-443.

- Greci V, Mortellaro CM, Olivero D, Cocci A, Hawkins EC. Inflammatory polyps of the nasal turbinates of cats: an argument for designation as feline mesenchymal nasal harmartoma. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2011; 13: 213-219.

- Head KW, Dixon PM. Equine Nasal and Paranasal Sinus Tumours. Part 1: Review of the Literature and Tumour Classification. Vet J. 1999;157(3):261-278.

- LaDouceur EEB, Michel AO, Bylicki BJL, et al. Nasal Cavity Masses Resembling Chondro-osseous Respiratory Epithelial Adenomatoid Hamartoma in 3 Dogs. Veterinary Pathology. 2016; 53(3): 621-624.

- Lane JG, Longstaffe JA, Gibbs C. Equine paranasal sinus cysts: A report of 15 Cases. Equine Vet J. 1987;19(6):537-544.

- LeRoith T, Binder EM, Graham AH, Duncan RB. Respiratory epithelial adenomatoid hamartoma in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009; 21:918-920.

- Mills SE. Nose, Paranasal Sinuses, and Nasopharynx. In: Mills SE ed. Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 6th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health. 2015:2672-2674.

- Pascoe JR. Ethmoid Hematoma. In: Smith BP, ed. Large Animal Internal Medicine, 5th Ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2015:561-562.

- Tremaine WH, Clarke CJ, Dixon PM. Histopathological findings in equine sinonasal disorders. Equine Vet J. 1999;31(4):296-303.

- Waguespack RW, Taintor J. Paranasal sinus disease in horses. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2011;33(2):E1-E11.

- Woodford NS, Lane JG. Long-term retrospective study of 52 horses with sinunasal cysts. Equine Vet J. 2006;38(3):198-202.