WSC 22-23:

Conference 8:

CASE II:

Signalment:

3 year, 7 month old female four-toed hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris)

History:

This adult female hedgehog had a brief (2-3 day) history of reduced appetite and unsteady gait before being found dead.

Gross Pathology:

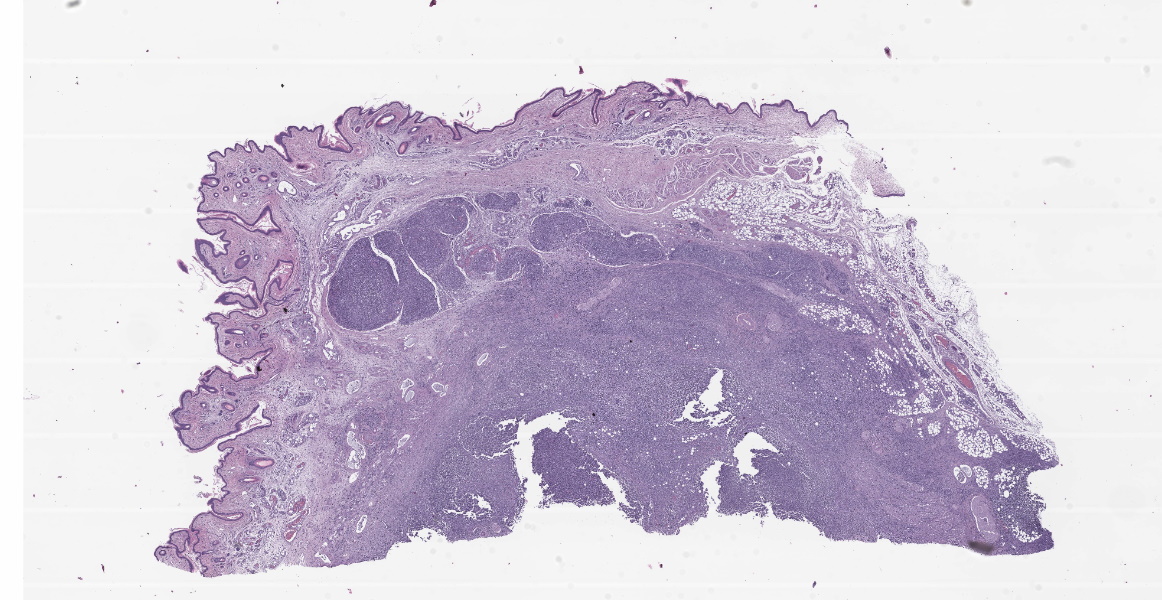

Gross examination revealed a large, solitary, well-demarcated, 1.3 cm x 1.2 cm x 1.8 cm mass in the left axillary region, approximately 0.2 cm lateral to the second left teat. An approximately 3.0 cm x 1.0 cm x 0.4 cm segment of the mass projected cranially through the subcutis, adjoining the axillary lymph node. On cut section, the mass was firm and tan with coalescing red segments. The skin overlying the mass was partially alopecic and hyperkeratotic, while the skin of the pinnae and dorsum exhibited moderate hyperkeratosis and flaking. Internally, two, approximately 2 mm diameter, tan, firm nodules were present in the dorsal aspect of the right lung and there was enlargement of a dorsocranial mediastinal lymph node (1.2 cm x 0.4 cm x 0.3 cm) which was mottled red and tan. Moderate thoracic effusion, approximately 2-3 ml of brown translucent fluid, was present. The spleen was mildly enlarged (5.6 cm x 1.5 cm x 0.4 cm) and diffusely dark purple.

Laboratory Results:

PCR targeting the ITS2 region of the fungal genome (5.8S - 28S), performed on FFPE tissue from the axillary mass, amplified two bands. The first, a 256 bp sequence, was 97.6% identical to GenBank No. NR_149340, Trichophyton erinacei strain ATCC 28443 (Blastn analysis, NCBI). Analysis of this sequence using the ISHAM (International Society for Human and Animal Mycology) Barcoding Database (https://its.mycologylab.org/; accessed June 2021) revealed this sequence to be greater than 99.4% identical to two strains of T. erinacei. 367 bp of trimmed DNA sequence was also obtained, and Blastn analysis showed this sequence to be 100% identical to several isolates of Malassezia restricta, including GenBank No. EU915456.

Microscopic Description:

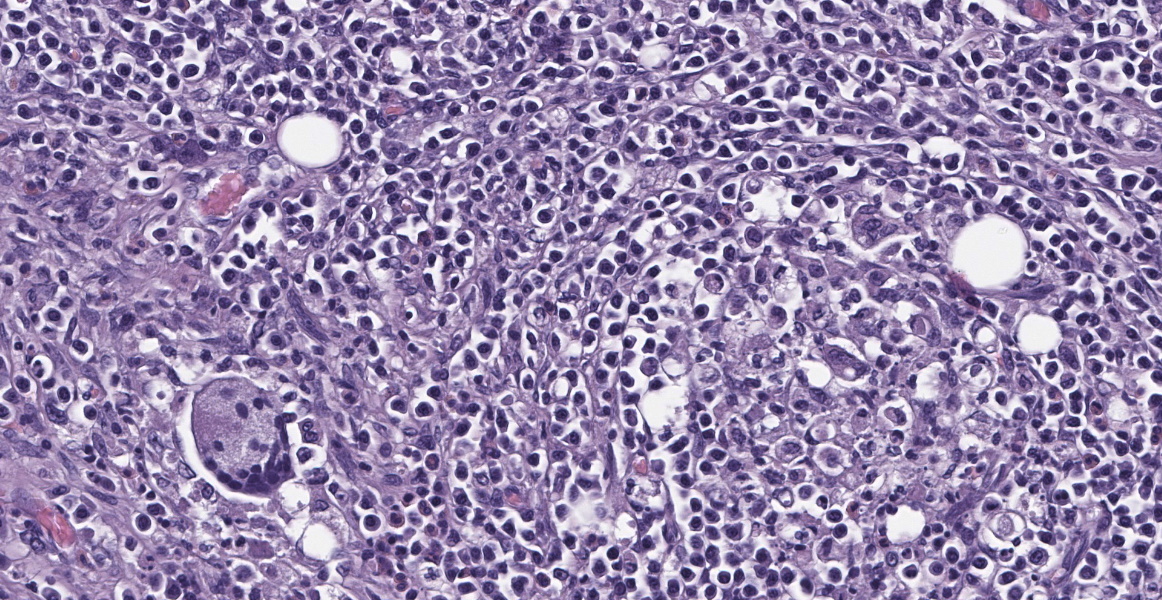

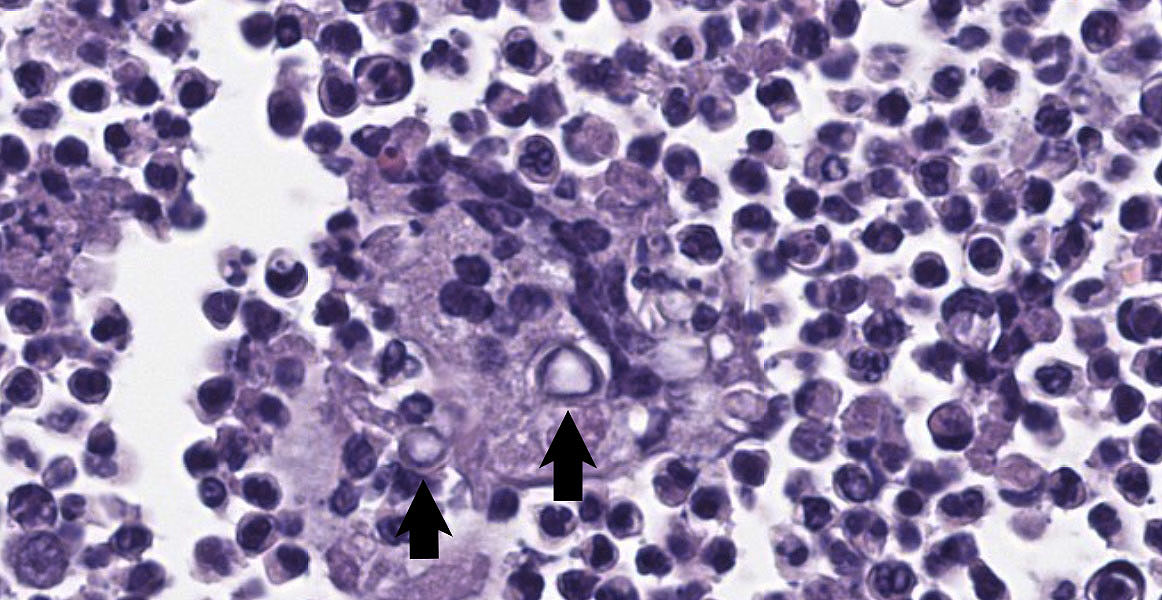

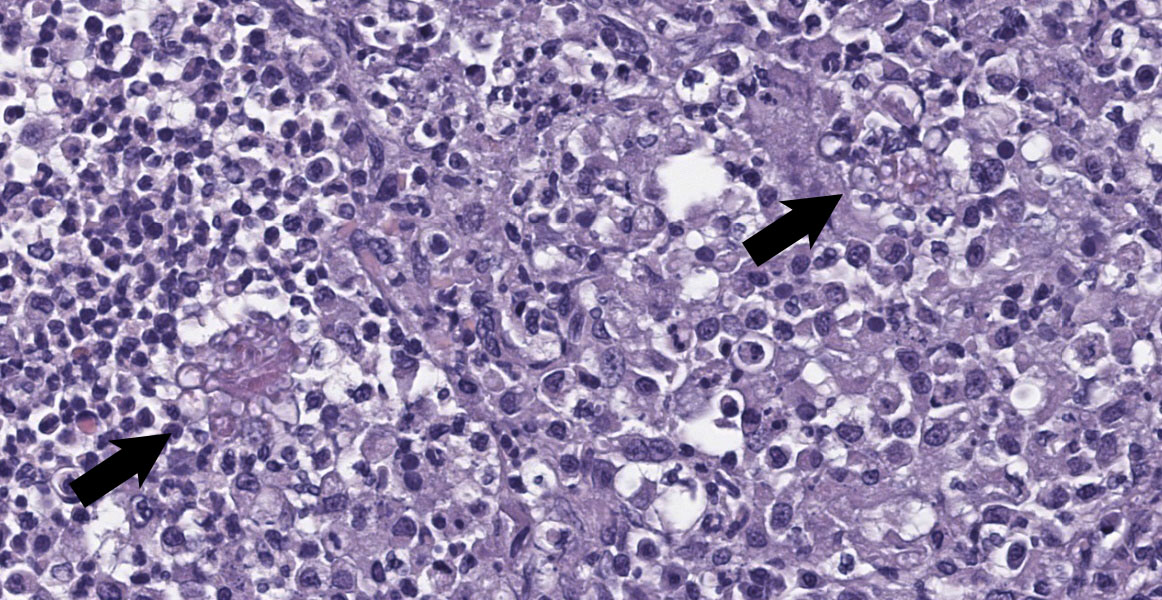

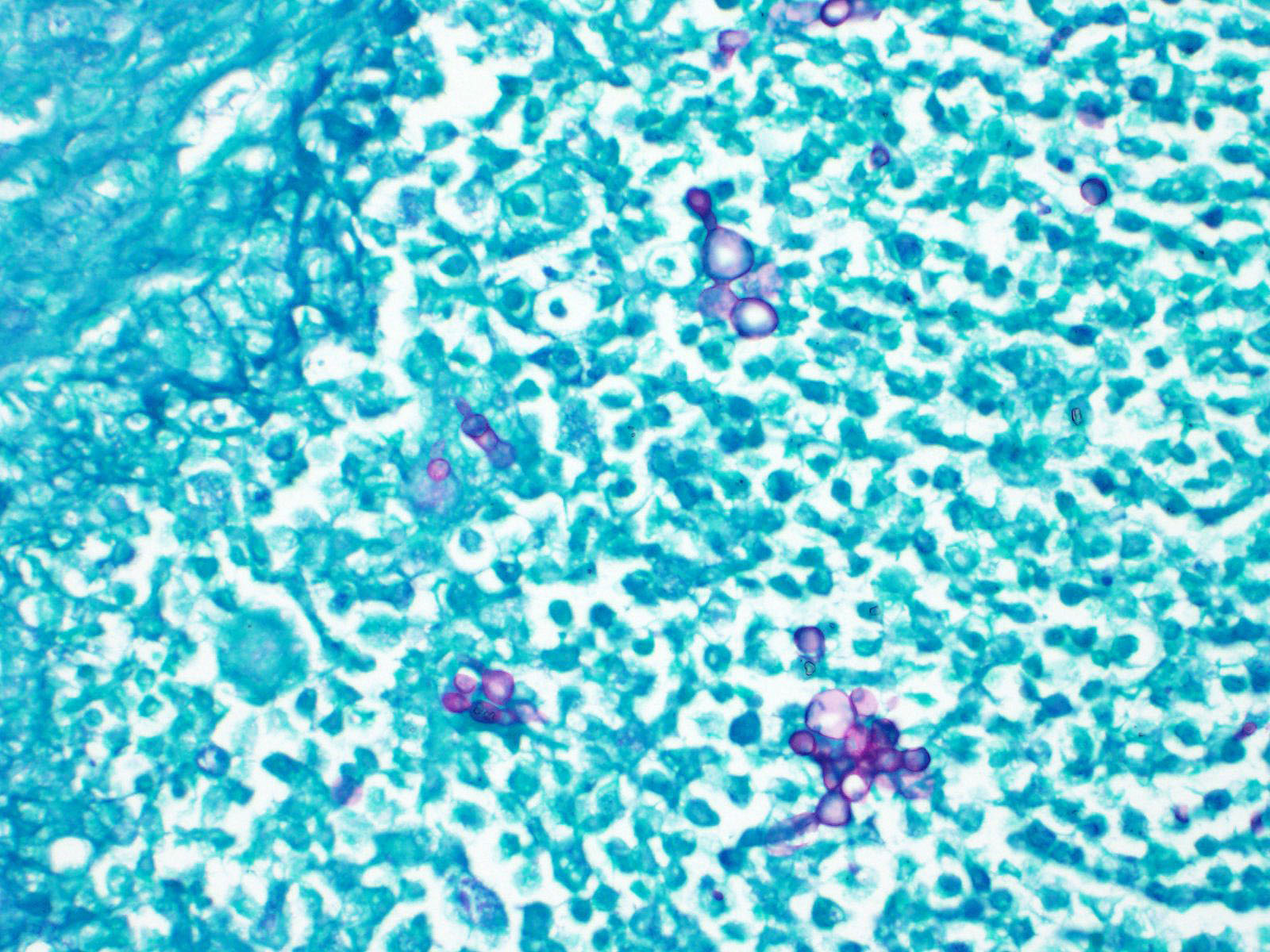

Axillary Skin: Markedly expanding and effacing the subcutis, and multifocally effacing skeletal muscle and extending into the dermis is a densely cellular inflammatory infiltrate. The infiltrate is composed of loose nodules of neutrophils, macrophages and multinucleated giant cells with occasional eosinophils, surrounded by a rim of epithelioid macrophages and a thin band of fibrous connective tissue (pyogranulomas). There is multifocal lysis of leukocytes within the center of some pyogranulomas. Similar inflammatory cells, accompanied by lymphocytes, plasma cells and scattered eosinophils and mast cells, fill the space between nodules, leaving little more than small islands of remnant adipose. Within pyogranulomas and within the cytoplasm of scattered multinucleated giant cells are low to moderate numbers of fungal elements. These are predominated by round to ovoid yeast-like structures ranging in diameter from approximately 5 µm up to approximately 15 µm in diameter which display occasional budding and often form tight clusters and knots. Rare elongate cytoplasmic protrusions are present and some yeast-like structures have thick, refractile capsules with an internal granular appearance. Chains of round or more elongate yeast-like structures, each individual unit separated from the next by septation with a waist-like indentation, are also present, as are branching true hyphae. A dense fibrous capsule which contains relatively few lymphocytes and plasma cells multifocally separates the inflammation from the surrounding tissue. In some areas, inflammation extends into the superficial dermis, where higher numbers of eosinophils and mast cells are present. Clear space (edema), pale basophilic granular material and/or inflammatory cells expand lymphatic vessels throughout the dermis. Endothelial cells lining vessels in areas of inflammation are enlarged with prominent nuclei with open chromatin. Degeneration, necrosis and regeneration are present in the inflamed skeletal muscle deep to the dermis. The overlying epidermis exhibits mild orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and there are scattered aggregates of yeast within the keratin (approximately 3 µm diameter).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Skin, axillary: Cellulitis, dermatitis, pyogranulomatous to mixed, chronic, locally extensive, marked, with intralesional and intracorneal fungal elements

Skin, axillary: Hyperkeratosis, orthokeratotic, chronic, diffuse, mild, with intracorneal yeast

Contributor’s Comment:

Systemic fungal infection identified in this four-toed hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) was most severe in the left axillary subcutis, where a large inflammatory mass was present, but also involved the lungs and multiple lymph nodes. Histology of the lungs and lymph nodes was similar to that described in the axillary region, with the additional findings of bronchiolitis and vasculitis in the lung, and vasculitis and rare intralesional bacteria (Gram negative bacilli) in the lymph nodes. Fungi within lesions were largely round to ovoid yeast-like forms of varying size, with occasional thick capsules and internal granularity, and multifocally forming chains. The appearance was somewhat reminiscent of Blastomyces species. Branching hyphae and chains of more elongate structures, representing abnormal arthroconidiation or pseudohyphae were also present (figure 3), as were rare elongate structures similar to germ tubes. PAS and GMS staining markedly enhanced visualization of fungi. Pan-fungal PCR utilizing primers targeting the ITS2 region amplified two separate and discrete bands, both of which were sequenced and were consistent with Trichophyton erinacei and Malassezia restricta, respectively; T. erinacei was suspected to be the primary etiology.

Trichophyton erinacei, formerly T. mentagrophytes var. erinacei and of the T. benhamiae complex, is a common isolate from hedgehog skin, with both clinical disease and subclinical carrier states being identified in free-ranging and pet European (Erinaceus europaeus) and four-toed hedgehogs.1 In one study investigating dermatophytosis in European hedgehogs at a wildlife center in France, over 79% of the T. erinacei culture-positive animals were asymptomatic and overall 20% of animals without skin disease were culture positive for T. erinacei.7 When present, disease associated with T. erinacei in hedgehogs presents with scaling, crusting and alopecia, including loss of spines; the head is often the focus of infection.1,2,7 While the histologic appearance of dermatophytosis in hedgehogs is not well described, it is expected to consist of fungal hyphae limited to the keratin layers and the hair/spine shafts, with mild inflammation and proliferative changes to include epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, as described in other species.5,9 In addition to the large axillary inflammatory mass, this patient had a focal area of fungal dermatitis on the foot which was reddened grossly (no flaking or crusting) and histologically exhibited orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis with intracorneal hyphae. This was interpreted as a potential second, more typical, area of T. erinacei dermatomycosis, although fungal identification was not pursued at this site.

Dermatophytosis is relatively common in both domestic animals and humans. It is caused by keratinophilic fungi, typically belonging to one of three genera: Trichophyton, Epidermophyton and Microsporum.3,9 Dermatophyte species are further classified according to natural history; these categories include the zoophilic species which primarily infect animals but can be transmitted to humans, the anthropophilic species which primarily infect humans, and the geophilic species which are typically found in the soil but can also infect animals and humans.3,9 Trichophyton erinacei is an example of a zoophilic dermatophyte, and one that may be considered an emerging pathogen based on increases in human and pet infections.2 Dermatophytes can be readily transmitted between animals and between animals and humans via direct contact with infected animals or indirect exposure to shed hairs (made brittle and easily broken by infection) and desquamated keratin containing infective spores.9 While normal, intact skin resists infection, minimal damage to the epidermis can predispose to infection.3 As alluded to above, the typical presentation consists of superficial lesions with fungi restricted to the stratum corneum of the epidermis and hair follicles and/or the hair shafts themselves. Deep infection by dermatophytes is rare in humans but can be prominent in animals, and includes both kerion (solitary inflammatory nodules, often with draining tracts) and pseudomycetoma (subcutaneous inflammatory nodules). Development of deep infection can result from implantation or furunculosis of affected follicles.9

Deep and/or systemic/disseminated trichophytosis in hedgehogs due to T. erinacei has not been described. In the sections examined from this case, folliculitis was not observed, nor was there specific evidence of furunculosis, such as hair or keratin within lesions. The presence of eosinophils, most notably in the dermis, was suggestive of furunculosis, however, and this remains a possibility, especially given the apparent chronicity of the case. One of the most interesting features in this case was the fungal morphology. Trichophyton species are typically hyphal when found superficially5 and morphologic forms like those seen in the current case have not been described with T. erinacei. However, T. rubrosum-associated deep mycoses in humans can contain atypical forms of the fungus, including Blastomyces-like yeast forms as seen here, as well as short, thickened hyphal fragments and arthroconidia.8,10,11,12 Descriptions of atypical dermatophyte morphology have to date been restricted to immunocompromised patients, in whom deep dermatophytoses are typically described, and have been limited to T. rubrosum in humans. While immune compromise was not confirmed in this hedgehog, marked lymphoid depletion in the spleen could indicate some degree of underlying immunodeficiency; the bone marrow was unremarkable. As in humans, superficial dermatophytosis was suspected to precede the deep infection in this hedgehog and more typical fungal hyphae were identified within the stratum corneum via GMS staining (figure 5).

Malassezia restricta, identified via PCR, was considered an incidental finding. This is a yeast that is part of the normal skin flora of humans and for which there are no descriptions of abnormal morphologies, or hyphal elements, in tissue. Yeast were present on the surface of the skin (figure 6) which may have been responsible for the positive PCR result. Confirmation of the fungal species within the deep lesions would require immunohistochemistry, in-situ hybridization or other advanced diagnostic modalities, none of which were pursued in this case.

Additional findings of note in this hedgehog included vacuolation in brain and spinal cord, predominantly affecting the white matter in the latter with more generalized distribution in the brain. This was similar to lesions described with “wobbly hedgehog syndrome (WHS),” a somewhat common idiopathic condition in hedgehogs and WHS could have contributed to those signs. This was a slightly unusual case in that WHS clinical signs are typically insidious in onset, rather than the acute onset in the current case, and other causes of vacuolation were not ruled out. It is possible that this lesion was incidental and the perceived neurologic signs the result of patient weakness and debilitation due to systemic fungal disease. There was also acute renal tubular degeneration and necrosis attributed to pulmonary disease and tissue hypoxia, and chronic hepatic and biliary changes suggestive of prior biliary obstruction.

This case highlighted the importance of ancillary testing for fungal disease, including culture and/or molecular diagnostics, rather than reliance on tissue fungal morphology alone.

Contributing Institution:

Wildlife Conservation Society, Zoological Health Program;

- https://oneworldonehealth.wcs.org

- wcs.org

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Haired skin: Dermatitis and cellulitis, pyogranulomatous, focally extensive, severe, with numerous fungi.

2. Haired skin: Hyperkeratosis, orthokeratotic, diffuse, mild, with superficial yeast.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a thorough report of Tricophyton erinacei infection in hedgehogs. Similar to T. erinacei, hedgehogs have a high prevalence of mecC-methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA), with carriage rates of 60-64% in various studies in wild European hedgehogs (Europeaus erineaus).4 The mecC gene encodes penicillin-binding protein 2c (PBP2c) and confers resistance to most beta-lactam antibiotics. Most mecC-MRSA infections occur in Europe, and it was initially isolated in bulk milk tanks and human infections in Europe.4 Dairy cattle were thought to be the reservoir, and it was believed that administration of beta-lactam antibiotics selected for resistant bacteria.4,6 While recent studies confirm that antibiotic exposure has indeed selected for mecC-MRSA resistance, a different antibiotic source has been incriminated: the cohabitant T. erinacei.

Penicillin-producing dermatophytes and penicillin resistant S. aureus were first documented in hedgehogs in the 1960s, and it was recently demonstrated that T. erinacei from wild hedgehogs encodes and expresses the same antibiotic-encoding genes as Penicillium chrysogenum, with some isolates actively producing benzylpenicillin.4 A subsequent in vitro study showed that the fungus has greater growth inhibition on mecC-deleted MRSA mutants compared to mecC-MRSA.6 These results strongly suggest that T. erinacei has imposed a selective pressure on S. aureus which favors resistance. Furthermore, phylogenetic studies have indicated that resistance of many mecC-MRSA lineages was acquired prior to the modern use of antibiotics. This is supported by the fact that T. erinacei isolates from hedgehogs in New Zealand have produced the same antibiotic resistance in mecC-MRSA, and these hedgehogs were imported from Europe in the 1800s.6

There is wide diversity but geographic clustering of mecC-MRSA isolates in hedgehogs.4 Most isolates lack the genetic variations required to infect humans and cattle, implying that methicillin-resistance did not originate in these other species.6 Furthermore, human and hedgehog isolates within the same geographic region have similar patterns of genetic variation.6 Coupling these facts with the high prevalence of mecC-MRSA in hedgehogs, researchers have concluded that hedgehogs are the natural reservoir for mecC-MRSA, and, for this strain, antibiotic resistance developed due to selective pressure from T. erinacei and predates medical use of antibiotics.6

References:

- Abarca ML, Castella G, Martorell J, Cabanes FJ. Trichophyton erinacei in pet hedgehogs in Spain: Occurrence and revision of its taxonomic status. Med Mycol. 2017;55:164-172.

- Cmokova A, Kolarik M, Dobias R, et al. Resolving the taxonomy of emerging zoonotic pathogens in the Trichophyton benhamiaeFungal Diversity. 2020;104:333-387.

- Donnelly TM, Rush EM, Lackner PA. Ringworm in small exotic pets. Sem Av Ex Pet Med. 2000;9:82-93.

- Dube F, Soderlund R, Salomonsson ML, Troell K, Borjesson S. Benzylpenicillin-producing Trichophyton erinacei and methicillin resistant Stapylococcus aureus carrying the mecC gene on European hedgehogs - A pilot study. BMC Microbiology. 2021; 21:212-222.

- Gregory MW, English MP. Arthroderma benhamiae infection in the Central African hedgehog, Erinaceus albiventris, and a report of a human case. Mycopathologia. 1975;55:143-147.

- Larsen J, Raisen CL, Ba X, et al. Emergence of methicillin resistance predates the clinical use of antibiotics. Nature. 2022; 602:135-141.

- Le Barzic C, Cmokova A, Denaes C, et al. Detection and control of dermatophytosis in wild European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) admitted to a French wildlife rehabilitation centre. J Fungi. 2021;7:74-87.

- Lillis JV, Dawson ES, Chang R, White CR. Disseminated dermal Trichophyton rubrum infection - an expression of dermatophyte dimorphism? J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1168-1169.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals Volume 1. 6th Elsevier; 2016.

- Nir-Paz R, Elinav H, Pierard GE, et al. Deep infection by Trichophyton rubrum in an immunocompromised patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5298-5301.

- Squeo RF, Beer R, Silvers D, Weitzman I, Grossman M. Invasive Trichophyton rubrum resembling blastomycosis infection in the immunocompromised host. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:379-380.

- Talebi-Liasi F, Shinohara MM. Invasive Trichophyton rubrum mimicking blastomycosis in a patient with solid organ transplant. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:798-800.