CASE II: 19N-0060 (JPC 4136398)

Signalment:

11-year-old castrated male domestic short-haired cat (Felis catus)

History:

The patient presented to the veterinary teaching hospital with a 2-3-month history of bumping into things, sitting in corners, vision loss, and behavior changes; he was reported to walk a fixed route in the home. A neurologic exam revealed absent menace responses, a left forelimb conscious proprioceptive deficit, and lumbosacral pain. A fundic examination showed intact retinas. These results did not point toward a clear diagnosis. Due to concerns about quality of life and financial constraints, his owners elected humane euthanasia without additional diagnostics (i.e. no radiographs, CT scan or biopsy were performed). A necropsy was performed to investigate the cause for the patient's clinical signs.

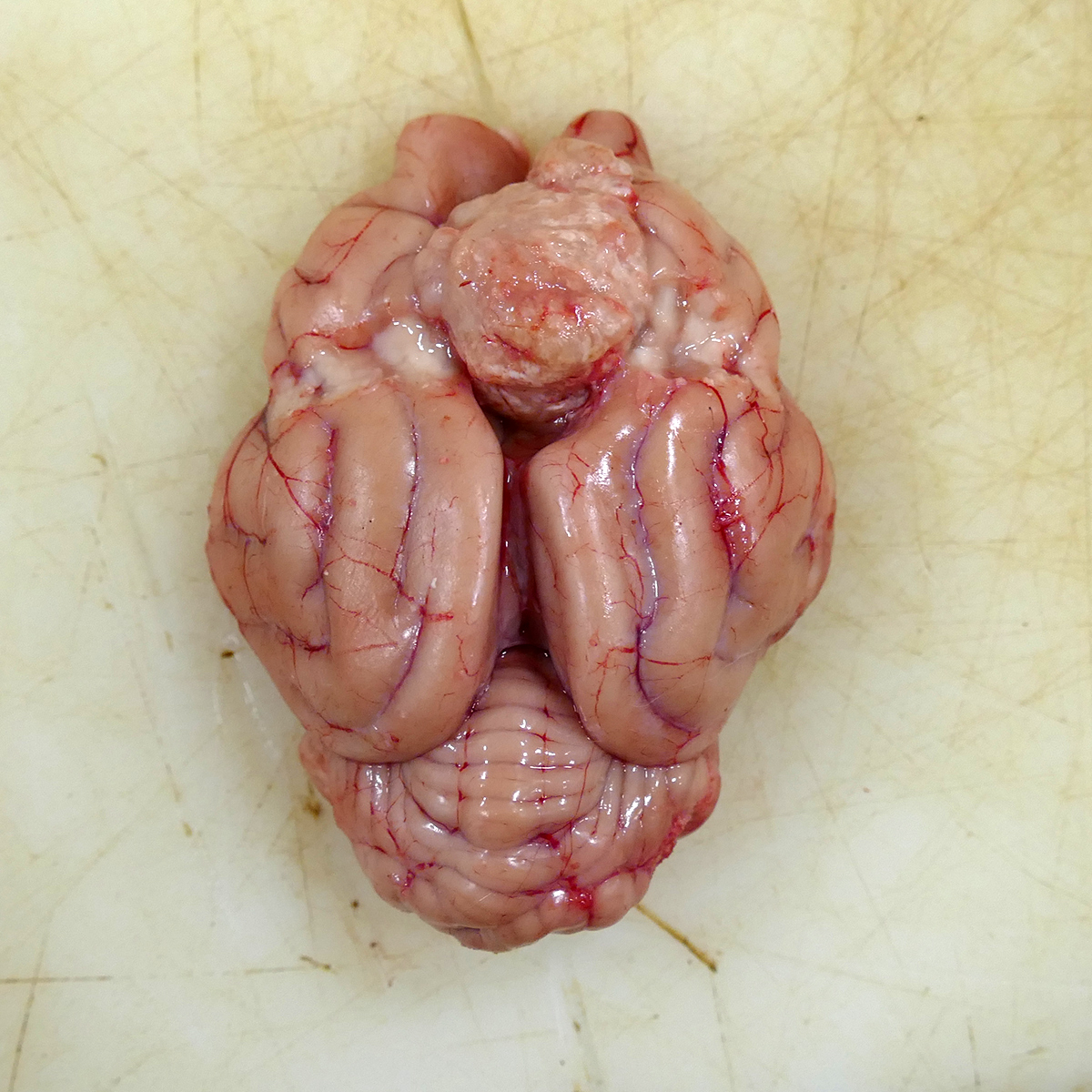

Gross Pathology:

Attached to the surface of the cerebrum and focally expanding the region between the rostral cerebral hemispheres and located 1 cm caudal to the most rostral aspect of the olfactory bulbs was a 2 x 1.7 x 1.8 cm, tan to light pink, semi-firm mass occupying the longitudinal fissure and mildly compressing the adjacent frontal cortex (Fig 1). On the cut surface, the mass was semi-firm, mottled tan and pink and slightly gritty. The primary differential for the well-demarcated, intracranial, extra-axial tumor at the time of necropsy was meningioma with the rule-outs of a primary CNS lymphoma, peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and granular cell tumor. No other organ systems demonstrated a neoplastic process.

Laboratory results:

No laboratory findings reported.

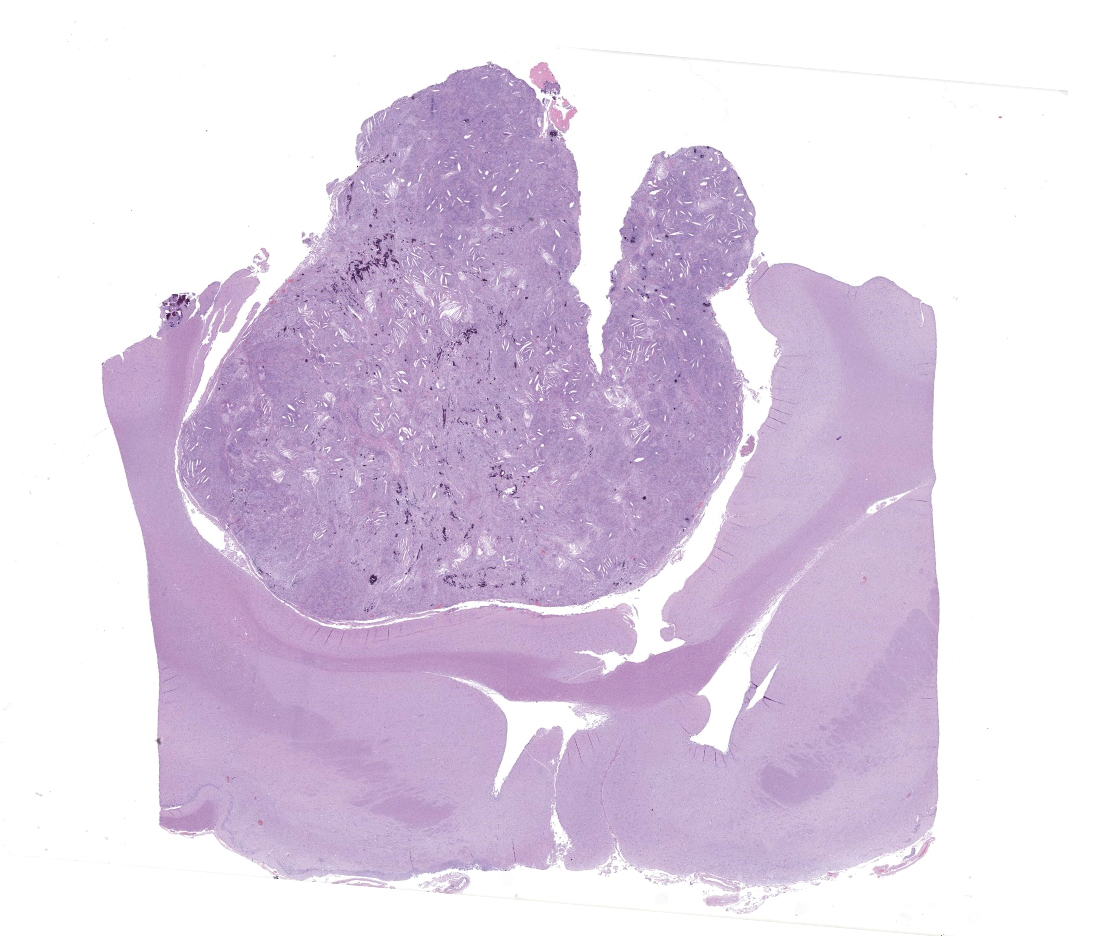

Microscopic Description:

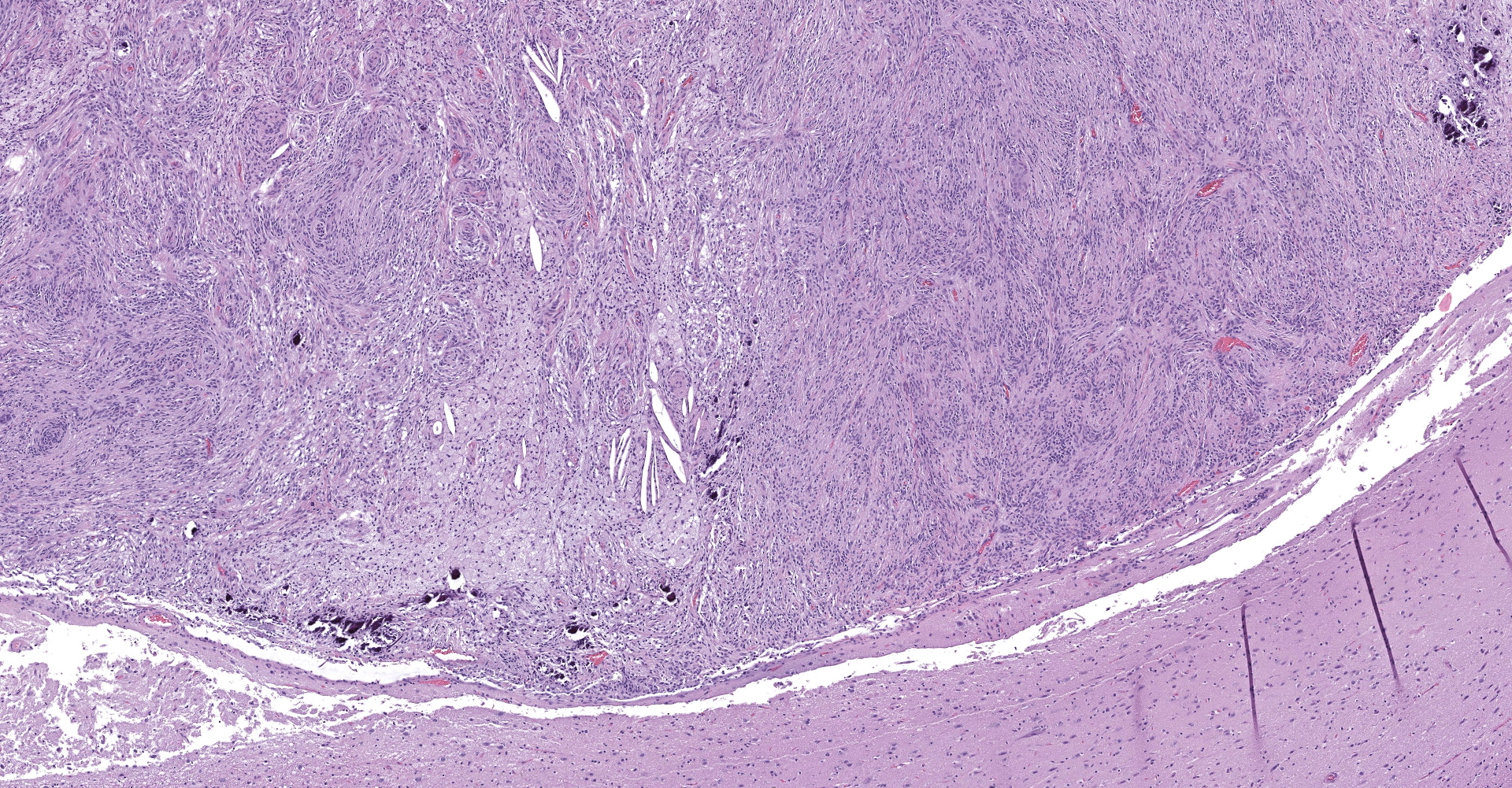

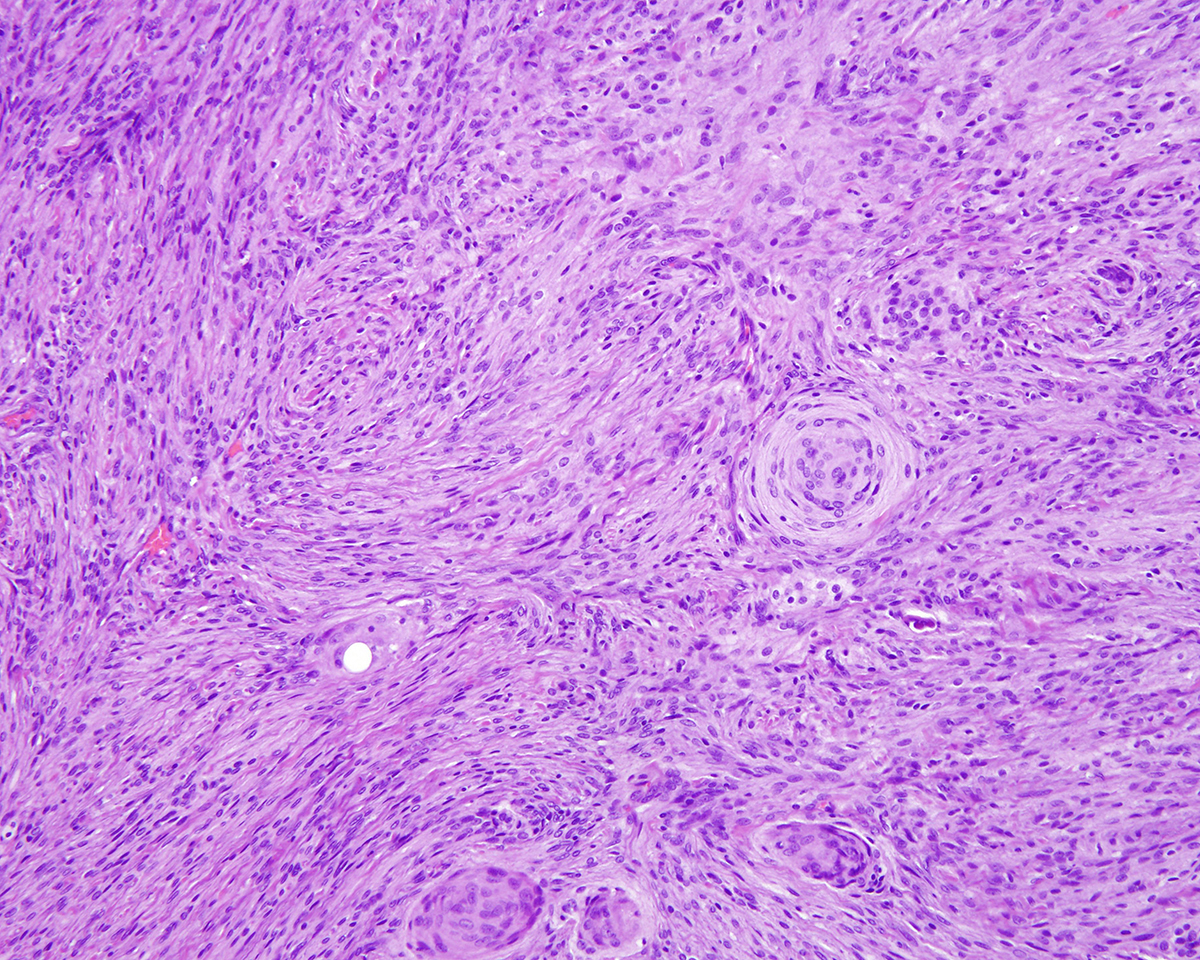

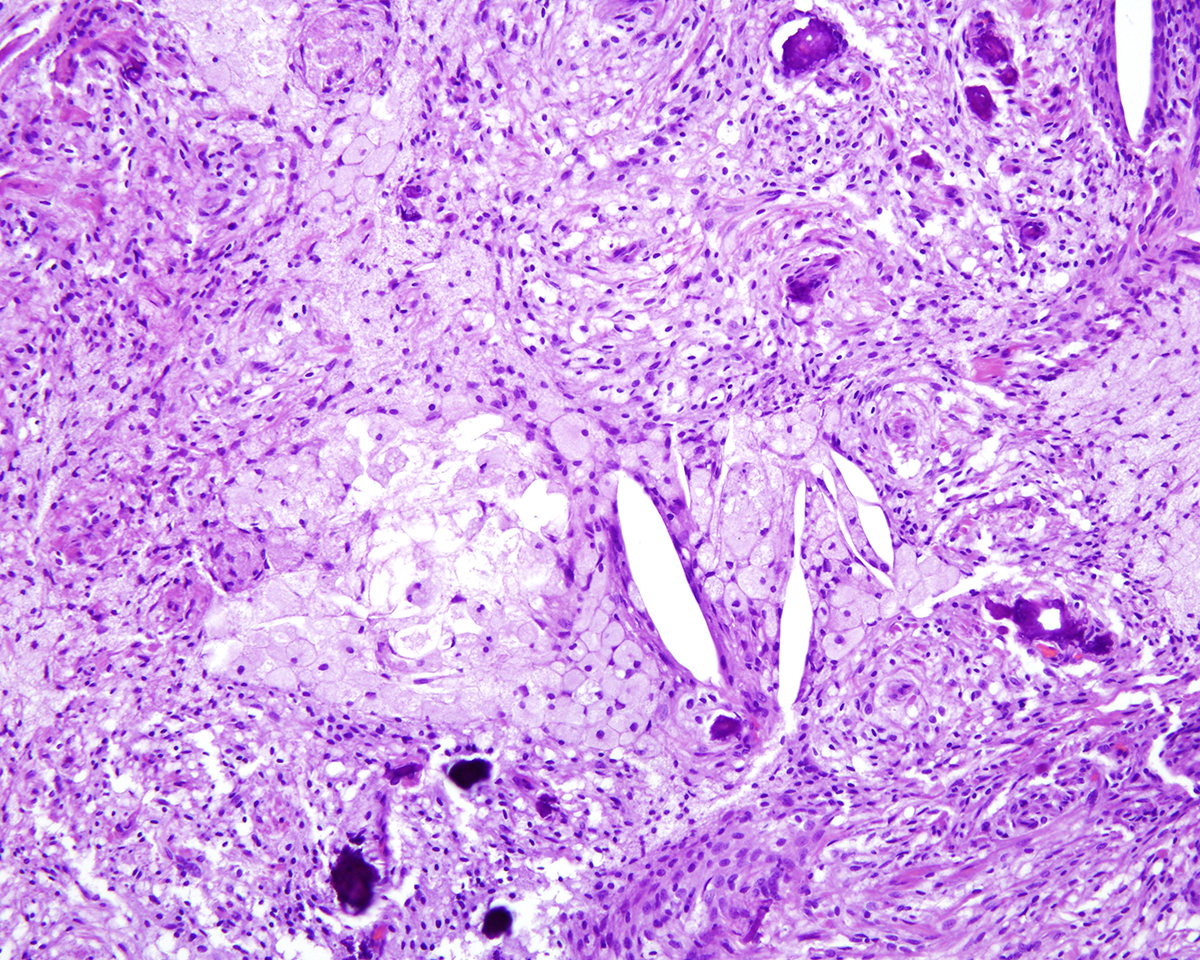

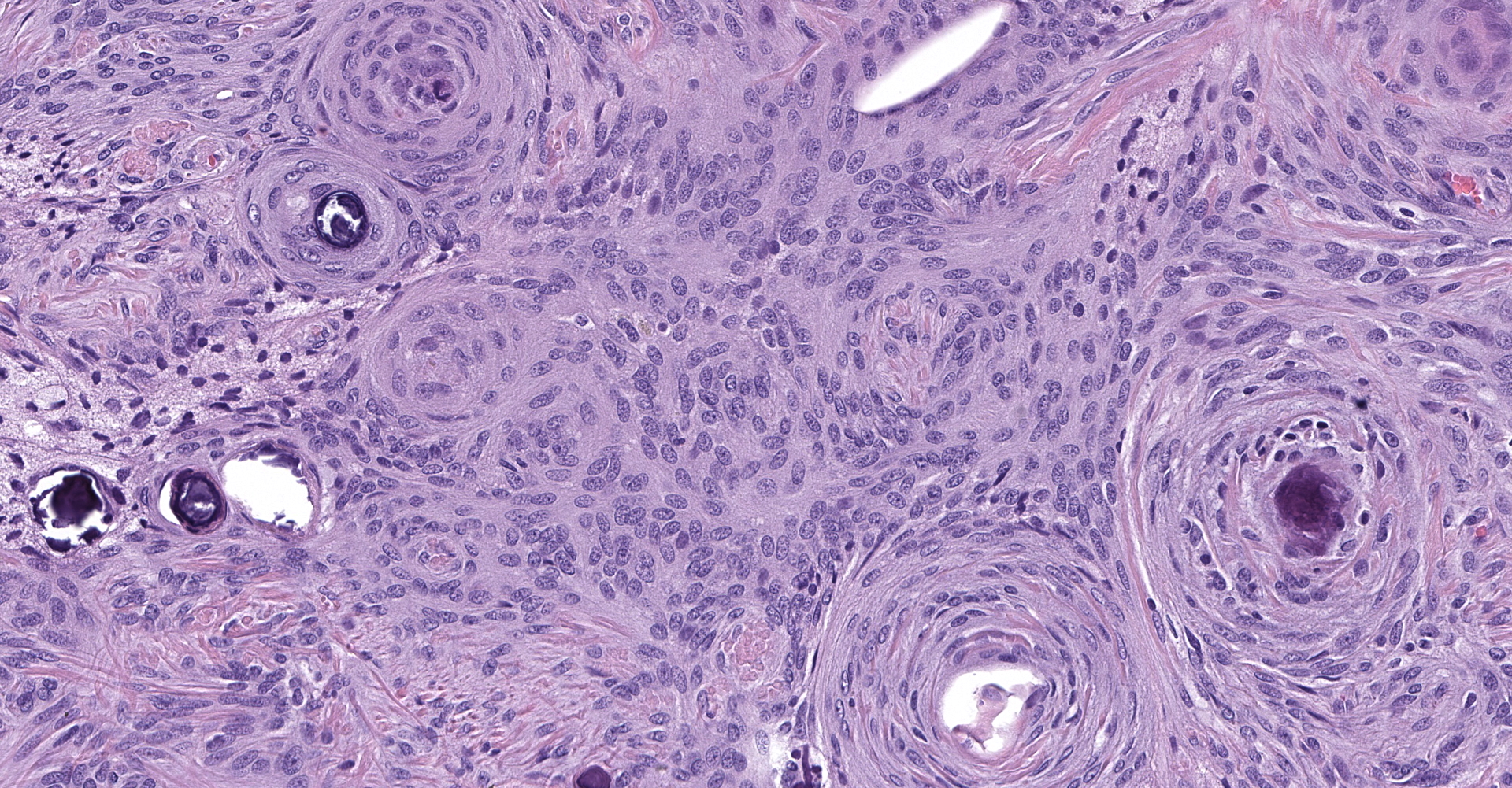

Markedly compressing the frontal cortex is an expansile, well-demarcated, non-invasive, unencapsulated, densely cellular neoplasm composed of short interlacing streams, bundles, and whorls of spindle to polygonal cells supported by a variably dense fibrovascular stroma with some stromal collagen bundles being prominent and serpiginous and occasionally mineralized. The neoplastic cells have variably distinct cell borders with small to moderate amounts of finely granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm. Nuclei are oval to elongated with vesiculated to finely stippled chromatin and occasionally have one distinct magenta nucleolus. The mitotic rate is low, with fewer than 1 mitotic figure per ten high powered fields (400x). Scattered and small to large aggregates of foamy macrophages surround acicular cholesterol clefts. Small numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and rare individual macrophages with intracytoplasmic pale brown material (hemosiderin) are scattered throughout the neoplasm. In many areas, there are several variably-sized foci of cellular dropout with replacement by eosinophilic cellular and karyorrhectic debris (necrosis) and individual cellular necrosis characterized by shrunken hypereosinophilic cells with pyknotic nuclei. Multifocally, at the center of a low number of whorls are concretions of lamellated hyaline acellular material that is occasionally mineralized (psammoma bodies). There are also multifocal, irregularly shaped accumulations of mineral (interpreted as dystrophic calcification). The brain parenchyma immediately adjacent to the mass is moderately to markedly compressed and focally concave. In a few regions, the cerebral cortex is hypercellular due to mildly increased numbers of glial cells (gliosis).

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

1. Intracranial mass: Meningioma with multifocal moderate to marked mineralization and cholesterol clefts; multifocal mild to moderate necrosis, hemosiderosis, and psammoma bodies.

2. Frontal cortex: Multifocal mild subacute to chronic cerebral cortical gliosis.

Contributor's Comment:

Meningiomas are the only tumor arising from meningothelial cells. In most reports, meningiomas have been diagnosed in patients over 7 and 9 years of age for dogs and cats respectively, although they have seldom been reported in young animals (< 6 months of age).10, 15 In a recent retrospective analyses of canine and feline primary intracranial neoplasia, meningiomas accounted for 22.3% and 59% of canine and feline brain tumors, respectively.10,15 They are the most common type of intracranial neoplasm in the cat in which there may be multiple masses present.4 Other commonly reported intracranial tumor types in cats are lymphoma, pituitary tumors, and gliomas.3,15 The most common neurological signs associated with meningiomas are lethargy, circling, seizures, and central blindness; however, some cats will not have neurologic signs.1,15

Meningiomas form as a result of the neoplastic transformation of meningothelial cells in the arachnoid membrane and pia mater. They are usually discrete variably shaped tumors with smooth surfaces and broad dural attachments.4, 16 They are solid, gray to tan (when fixed), firm and sometimes gritty on the cut surface. Meningiomas are expansile and compress, but infrequently invade the brain. A significantly decreased incidence in their location occurs from the olfactory bulbs caudally correlating directly with a decrease in the number of arachnoid villi.9,16 In dogs, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor in the spinal canal and are most common at the level of C1-4 spinal cord segments; the frequency decreases caudally.16

In cats, meningiomas are usually supratentorial, multinodular, well-defined, expansile and locally compressive. They are variably sized and may exist simultaneously in multiple sites; in cats, they may occur in the tela choroidea of the third ventricle.4,6,9,16 Feline meningiomas are rarely invasive and are more easily separated from the brain parenchyma than the more tightly adherent canine menigiomas.4,6,9

Meningiomas in dogs are mostly intracranial but spinal cord, orbital, paranasal, and cutaneous meningiomas also occur.4,8,9,10,14,16 While extracranial cutaneous meningiomas are rare in both humans and veterinary species, two cases of canine periocular extracranial cutaneous meningiomas have been recently described.14 In horses and dogs, the paranasal meningioma is a rare variant that forms from meningeal arachnoid cells either within or outside of skull bones as the cranium develops.4 Paranasal meningiomas in 10 canine patients were considered to be malignant because of their anaplastic features and aggressive behavior resulting in invasion into the cranial cavity.11 The clinical presentation of primary orbital (optic nerve) meningiomas includes exophthalmos due to a space-occupying mass behind the globe and blindness due to compression of the optic nerve.8 Meningiomas are reported sporadically in horses, cattle, pigs, and sheep.9, 16

Meningiomas display both mesenchymal and epithelial-like features showing spindle cell morphology with deposition of collagenous stroma or polygonal cell morphology. The following are the most common subtypes of meningiomas in dogs applying the criteria of the latest (2007) human WHO classification system for the histological classification of the subtypes and for the grading of canine meningiomas.4,6,9,16

Meningiomas in dogs are mostly intracranial but spinal cord, orbital, paranasal, and cutaneous meningiomas also occur.3,7,8,10,12, 15 While extracranial cutaneous meningiomas are rare in both humans and veterinary species, two cases of canine periocular extracranial cutaneous meningiomas have been recently described.12 In horses and dogs, the paranasal meningioma is a rare variant that forms from meningeal arachnoid cells either within or outside of skull bones as the cranium develops.3 Paranasal meningiomas in 10 canine patients were considered to be malignant because of their anaplastic features and aggressive behavior resulting in invasion into the cranial cavity.10 The clinical presentation of primary orbital (optic nerve) meningiomas includes exophthalmos due to a space-occupying mass behind the globe and blindness due to compression of the optic nerve.7 Meningiomas are reported sporadically in horses, cattle, pigs, and sheep.8, 15

Meningiomas display both mesenchymal and epithelial-like features showing spindle cell morphology with deposition of collagenous stroma or polygonal cell morphology. The following are the most common subtypes of meningiomas in dogs applying the criteria of the latest (2007) human WHO classification system for the histological classification of the subtypes and for the grading of canine meningiomas: 3,4,8,15

Meningioma grade I subtypes:

1. Transitional (mixed):

a. Features of both meningothelial and fibrous meningiomas.

b. Syncytial cell clusters or concentric whorls around capillaries or psammoma bodies.

c. Well-demarcated lobules mixed with meningothelial cells.

d. The majority of canine meningiomas are of this type.

2. Meningothelial:

a. Solid, moderately cellular lobules of polygonal cells with ill-defined borders and abundant cytoplasm; frequent cytoplasmic invaginations into the nucleus.

b. Low mitotic index; giant cells with bizarre nuclei can be seen.

c. Very common.

3. Psammomatous:

a. A transitional pattern background

b. Prominent whorls with abundant, concentric layers of hyaline material that frequently have central aggregates of mineral (psammoma bodies).

4. Angiomatous (angioblastic):

a. Numerous large or small blood vessels (usually over 50% of the mass)

b. Rare in domestic animals.

5. Microcystic:

a. Spindle shaped neoplastic cells with loosely arranged, elongate processes that form small or large, clear, intracytoplasmic and interstitial vacuoles (micro- and macrocysts)

b. This pattern can have admixed areas of transitional and/or fibrous patterns.

6. Fibrous (fibroblastic):

a. Spindle shaped neoplastic cells arranged in long interlacing bundles

b. The neoplastic cells are separated by variable amounts of collagen and reticulin.

c. These frequently co-exist with the microcystic subtype

d. Uncommon.

7. Secretory:

a. Newly recognized.

b. Epithelial-like, cytokeratin positive glands containing intracytoplasmic, round PAS positive globular structures mixed with areas representing the more common subtypes.

c. These must be distinguished from adenocarcinoma.

Atypical meningioma grade II subtypes:

Features: Some meningiomas are assigned a grade II status based on their aggressive biological behavior (subtypes listed below). Additionally, a tumor with cellular features consistent with a grade I meningioma that also exhibits brain invasion is re-assigned to a grade II category. Finally, a meningioma is assigned an atypical classification when it has one or more of the common histological patterns but also has features of either:

· A mitotic count of at least 4 mitoses per 10 high power fields ?OR-

· At least 3 of the following criteria:

o Loss of normal architectural pattern replaced by cell sheeting

o Small cell formation with a high N/C ratio

o Nuclear atypia or macronuclei

o Hypercellularity

o Spontaneous necrosis

Subtypes:

1. Atypical meningiomas (irrespective of the histological subtype):

a. Hypercellular, moderate to marked cellular atypia,

b. Small cells with a high N/C ratio

c. Sheets of neoplastic cells that do not conform to a specific pattern

d. Areas of necrosis, more than 4 mitoses per 10 high power fields, and brain invasion.

2. Chordoid (myxoid):

a. Vacuolated neoplastic cells with round nuclei

b. Cords and trabeculae supported by a myxomatous matrix that is positive-staining for PAS, alcian blue, and mucicarmine.

3. Clear cell:

a. Sheets of polygonal cells with clear cytoplasm due to glycogen content (non-diastase resistant, PAS-positive cytoplasmic staining).

b. Rare.

Malignant meningioma Grade III subtypes:

Features: Extreme cellular anaplasia, frequent mitoses (more than 20 mitoses per 10 high power fields), high cellularity, bizarre mitotic figures, extensive necrosis, brain invasion and metastasis.

Histologic subtypes:

1. Papillary:

1. Neoplastic cells arranged in papillary forms supported by a fibrovascular stroma.

2. Rare in domestic animals.

2. Rhabdoid:

1. Non-cohesive cells with a large vesiculate nuclei and intracytoplasmic paranuclear, eosinophilic globular, inclusion-like, bodies.

2. Most cells have features of grade III malignant variants.

3. Rare in dogs.

In canines, approximately half of meningiomas are classified as benign grade I followed by atypical grade II; malignant grade III tumors are rare.12

In one study of 38 feline meningiomas, grade III tumors were not identified and the researchers questioned whether current grading systems are relevant for feline meningiomas.7,10 In further contrast to the dog, cat meningiomas have a remarkably consistent and uniform histological appearance characterized by prominent whorling of elongate cells in a collagen rich matrix in a pattern similar to the classical transitional and fibroblastic subtypes; these tumors usually present as an even mixture of both.4,9, 16 Additionally, repeatable findings are elongate linear foci of mineralization, necrosis, polymorphonuclear infiltrates and clusters of cholesterol crystals, but generally only a few psammoma bodies. A lack of nuclear atypia and mitotic figures, the presence of a relatively uniform cell type, and benign behavior are features most consistent with a grade I tumor.4,9,16 As a result, it appears the fairly repeatable, though varying, types of neoplastic cells in combination with the cytologically uniform cellular features, create a situation where feline meningiomas do not easily fit into any one existing subtype of the human 2007 WHO classification system.7,9,10 Furthermore, the morphologic uniformity and overall similarity in biologic behavior among feline meningiomas makes a classification into different morphologic subtypes unnecessary and a grading system biologically meaningless.

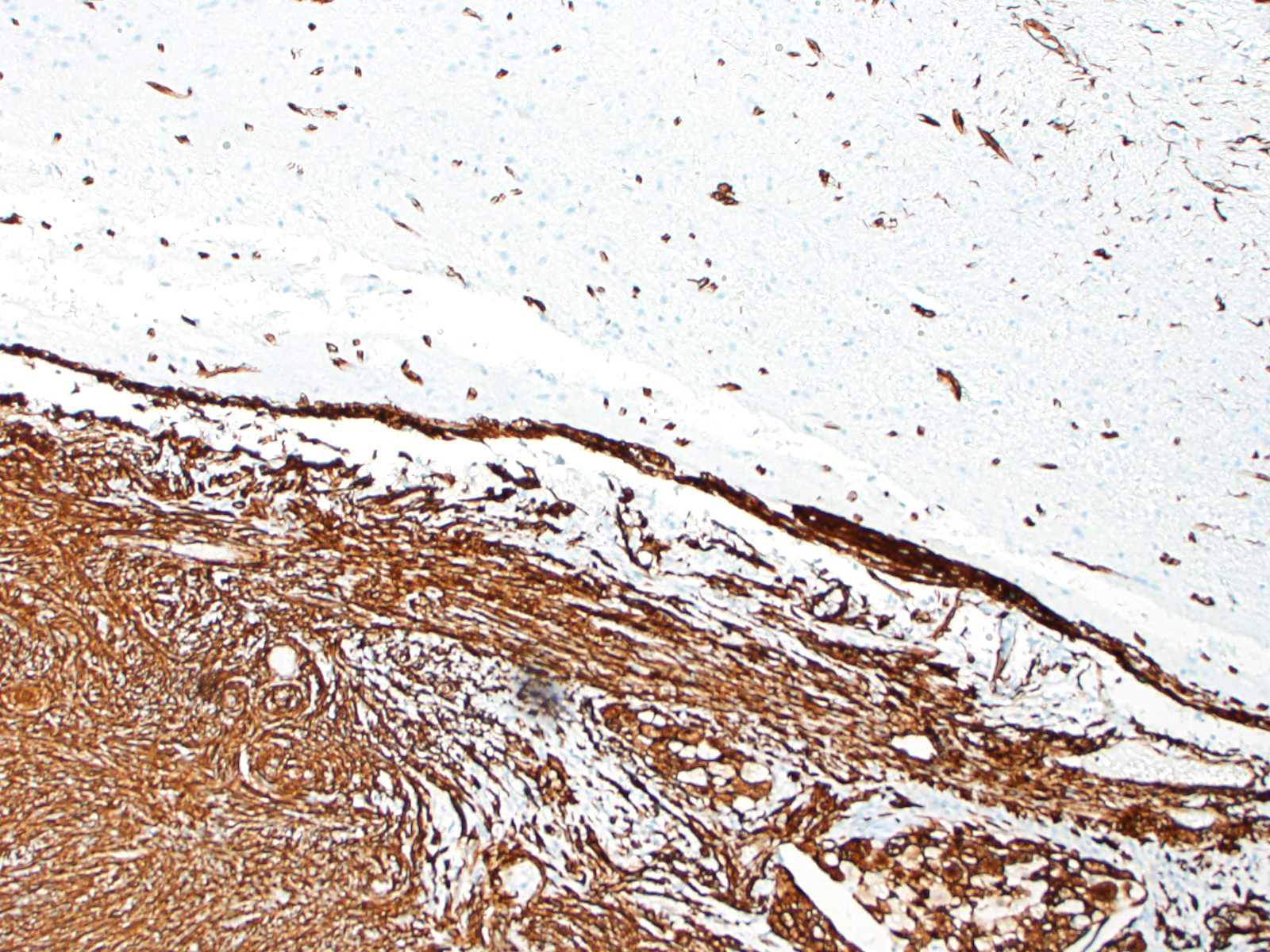

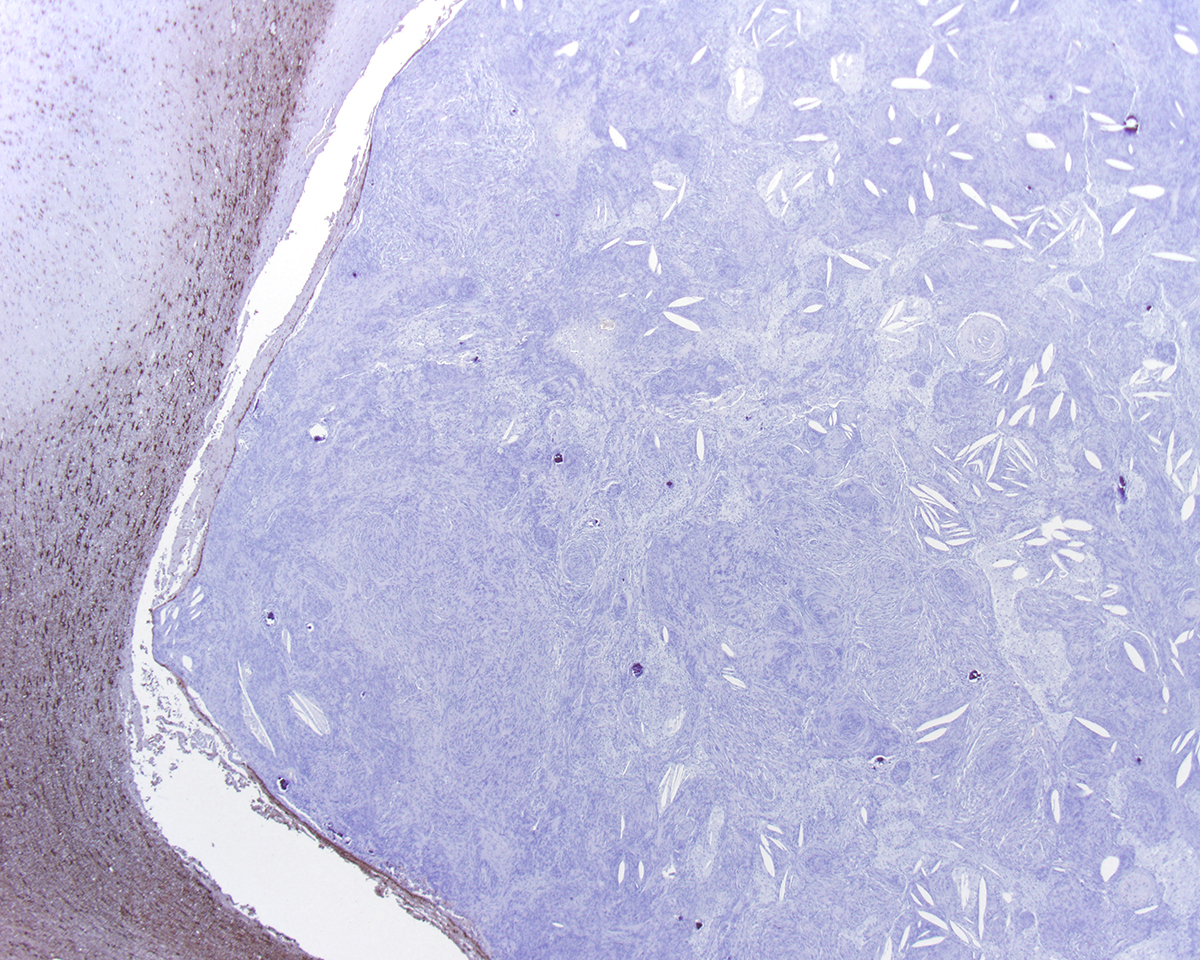

Most meningiomas stain positively for vimentin and negatively for GFAP. Staining for cytokeratin, neuron specific enolase and S100 usually yield positive results but with variable (minimal to moderate) expression.3,4 Frequently, meningiomas are immunohistochemically positive for CD34 and E-cadherin.4 In canines, the most reliable confirmation of a diagnosis of a canine meningioma still relies on transmission electron microscopy; most are characterized by numerous interdigitating cell processes, cytoplasmic intermediate filaments, desmosomes, and hemidesmosomes.6

In this case, the gross findings were highly suggestive of a meningioma due to its location (supratentorial and cerebral convexity). Its characteristic histologic features distinguished it from other intracranial tumors such as peripheral nerve sheath tumor and lymphoma. The variable histologic patterns present within this single neoplasm is typical for feline meningiomas. The neoplastic cells exhibited diffuse strong cytoplasmic positivity for vimentin. They did not express GFAP. Scattered cells exhibited minimal faint cytoplasmic positivity for S100. For this case, the clinical presentation of blindness is within the realm of what has been reported. Despite the dorsal location of the neoplasm, it is suspected that the cause for blindness in this patient is related to the tumor's space occupying effects and subsequent compression of the optic nerves and/or chaism; however, disruption of pathways to the occipital lobe cannot be ruled out. While meningiomas may enter the optic foramina, this was not observed in this case.

Contributing Institution:

University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

2015 Linden Dr.

Madison, WI 53706

https://www.vetmed.wisc.edu/departments/pathobiological-sciences/

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Meningioma.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an outstanding and very thorough overview of meningioma, the most common brain tumor affecting both cats and humans.

Dr. Harvey Cushing first coined the term "meningioma" in 1922; however, Dr. Felix Platter is credited with the oldest written record of what could be a meningioma in the existing literature, first describing this intracranial tumor in 1614. Dr. Platter was a prominent Swiss physician and anatomist who was also the first physician to dissect a human body in Germany. One of his patients, Caspar Bonecurtius, developed a progressively altered mental status, eventually became comatose, and died six months later. Dr. Platter performed an autopsy and described, "A round fleshy tumor, like an acorn. It was hard and full of holes, and as large as a medium-sized apple. It was covered by its own membrane and entwined with veins. However, it was free of all connections of the matters of the brain so much that when it was removed by hand, it left a remarkable cavity."2

Multiple additional reports describing tumors now known as meningiomas were published in the years that followed. Over 150 years after Dr. Platter, a French surgeon named Antoine Louise published a case series on meningioma entitled "Fungueuses de la dure ?mere" or "Fungating mass of the dura matter" in 1771. In 1863, Dr. Virchow identified granules within meningiomas and named the granular bodes "psammomas" (sand-like). In the United States, Dr. William Keen successfully resected a meningioma in 1887.2

Today, approximately 33.8% of all reported primary brain and central nervous system tumors in the United States (in humans) are meningiomas. Inherited susceptibility has been suggested based on family histories as well as gene studies in DNA repair genes. People with mutations in the neurofibromatosis gene (NF2) have a substantially increased risk. High dose ionizing radiation has also been identified as an established risk factor. Because women are twice as likely as men to develop meningioma and these tumors express progesterone receptors, an etiologic role for hormones in human meningiomas has also been proposed. No such female sex predilection exists for dogs or cats.12,15

The primary environmental risk factor for humans is exposure to ionizing radiation, such as demonstrated in data obtained from atomic bomb survivors showing greatly increased risk of meningioma. Evidence also exists for lower dose level exposure, such as patients with a history of full mouth radiographs having significantly increased risk for meningioma. 17

In humans, meningiomas often have a long latency period (20-30 years or more) and the prevalence of subclinical disease is present in up to 2.8% of women as suggested by autopsy results. In fact, many meningiomas are discovered incidentally via MRIs for conditions such as head trauma and are often managed "conservatively", without surgical removal unless clinically warranted. 17

Unlike canines, feline meningiomas are not typically subtyped. The features exhibited in this case, including whorls around psammoma bodies and steams of collagenous matrix, would be consistent with a transitional meningioma, the most common subtype affecting canines.

References:

1. Adamo, P. F., Forrest, L., & Dubielzig, R. (2004). Canine and feline meningiomas: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Compendium, 26, 951-965.

2. Bir SC, Maiti TK, Bollam P, Nanda A. Felix Platter and a historical perspective of the meningioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;134:75-78.

3. Johnson, G. C., Coates, J. R., & Wininger, F. (2014). Diagnostic immunohistochemistry of canine and feline intracalvarial tumors in the age of brain biopsies. Veterinary pathology, 51(1), 146-160.

4. Kennedy, P. C., & Palmer, N. (2013). Neoplastic Diseases of the Nervous System. In: Pathology of domestic animals. 396-398 Academic Press.

5. Kishimoto TE, Uchida K, Chambers JK, Kok MK, Son NV, Shiga T, Hirabayashi M, Ushio N, Nakayama H. A retrospective survey on canine intra-cranial tumors between 2007 and 2017. J Vet Med Sci. 2020 Jan 17;82(1):77-83.

6. Koestner, A., Bilzer, T., Fatzer, R., Schulman, Y., Summers, B.A., & Van Winkle, T.J. Histological classification of tumors of the nervous system of domestic animals. In: WHO International Histological Classification of Tumors of Domestic Animals, Vol. 5. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1999: 27-29.

7. Mandara, M.T., Pavone, S., Brunetti, B., Mandrioli, L., 2010. A comparative study of canine and feline meningioma classification based on the WHO histological classification system in humans. In: Proceedings of the 22nd Symposium ESVN-ECVN, Bologna, 24?26 September 2009. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 24, 238.

8. Mauldin, E. A., Deehr, A. J., Hertzke, D., & Dubielzig, R. R. (2000). Canine orbital meningiomas: a review of 22 cases. Veterinary ophthalmology, 3(1), 11-16.

9. Meuten, D. J. (Ed.). (2016). Tumors of the Nervous System. In: Tumors in domestic animals. 864-869. John Wiley & Sons.

10. Motta, L., Mandara, M. T., & Skerritt, G. C. (2012). Canine and feline intracranial meningiomas: an updated review. The Veterinary Journal, 192(2), 153-165.

11. Patnaik, A. K., Lieberman, P. H., Erlandson, R. A., Shaker, E., & Hurvitz, A. I. (1986). Paranasal meningioma in the dog: a clinicopathologic study of ten cases. Veterinary pathology, 23(4), 362-368.

12. Saito R, Chambers JK, Kishimoto TE, Uchida K. Pathological and immunohistochemical features of 45 cases of feline meningioma. J Vet Med Sci. 2021 Aug 6;83(8):1219-1224

13. Sturges, B. K., Dickinson, P. J., Bollen, A. W., et al. (2008). Magnetic resonance imaging and histological classification of intracranial meningiomas in 112 dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 22(3), 586-595.

14. Teixeira, L. B. C., Pinkerton, M. E., & Dubielzig, R. R. (2014). Periocular extracranial cutaneous meningiomas in two dogs. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 26(4), 575?579.

15. Troxel, M. T., Vite, C. H., Van Winkle, T. J., et al. (2003). Feline intracranial neoplasia: retrospective review of 160 cases (1985?2001). Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 17(6), 850-859.

16. Vandevelde, M., Higgins, R., & Oevermann, A. (2012). Veterinary neuropathology: essentials of theory and practice. 147-150. John Wiley & Sons.

17. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314.