Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

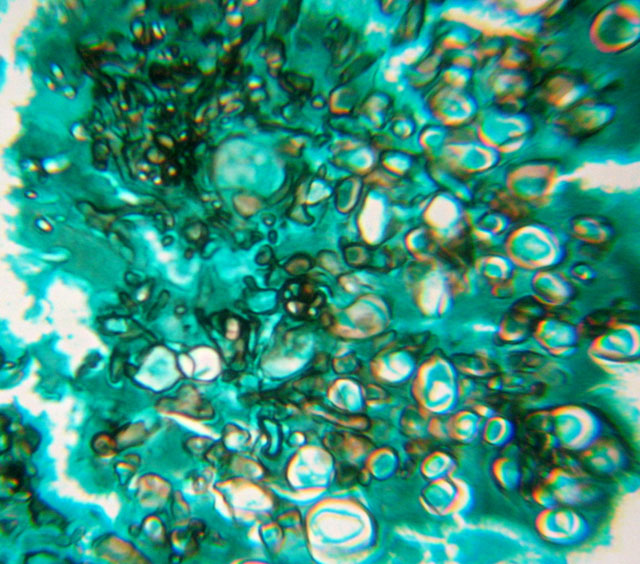

Organisms were strongly positive using periodic acid-Schiff stain. Mycelia was also evidenced with the Gomoris methenamine-silver stain (Fig. 3-3). Both are used to demonstrate the fungal nature of the granules.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

This type of dermatophytic infection differs from dermatophytosis, in which lesions are restricted to epidermal structures.(2) Pseudomycetomas must be distinguished from fungal mycetomas, or eumycotic mycetomas. True mycetoma is a nodular inflammation with fibrosis, fistulae draining from deep tissue, the presence of grain, and an indolent infection of certain fungi or higher bacteria inoculated into subcutaneous tissues.(4) In pseudomycetomas there are 1) multiple lesions, 2) lack of skin trauma history, 3) association with dermatophytes, most commonly Microsporum canis (1, 2, 7) histologically, lack of true cement material and a more abundant Splendore-Hoeppli reaction.(1,2,4) Additionally, in pseudogranules, there are fewer hyphal filaments than in true eumycotic granules. Pseudomycetoma granules have a sequential development, characterized by the presence of small to large clusters of mycelia elements.(4)

It is unclear why the cat developed a pseudomycetoma.(9) Several hypotheses on the pathogenesis of the disease have been proposed. In contrast to the supposed traumatic origin of a mycetoma, in pseudomycetoma some authors propose that mycelial elements escape from the hair follicle into the surrounding tissues (1, 7) where they aggregate and induce an immune response. The exact immunological mechanism responsible for the formation of the granules is much debated, as well as the predisposition of Persian cats to the disease.(1) There is a recent report of an intraabdominal pseudomycetoma in a Persian cat who had no suspicion of immunosuppression, no history of cutaneous ringworm infection, and no prior abdominal surgery. Possible sources of this infection include: ingestion of infected foreign material, secondary to prior castration, inoculation from rectal thermometer, or other penetrating wound.(9) A chronic evolution is the rule, and the prognosis is fair even with systemic antifungal therapy of long duration.(2)

A definitive diagnosis of pseudomycetoma involves a combination of histopathology and either identification of the causal organism by fresh tissue culture or by identification of the organism by immunohistochemical stains.(1,9)

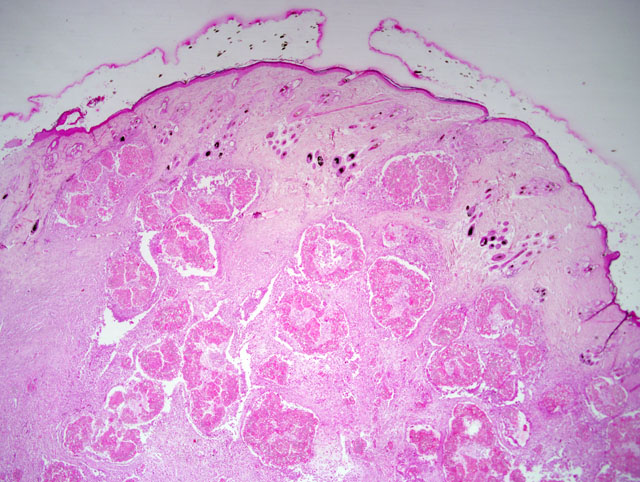

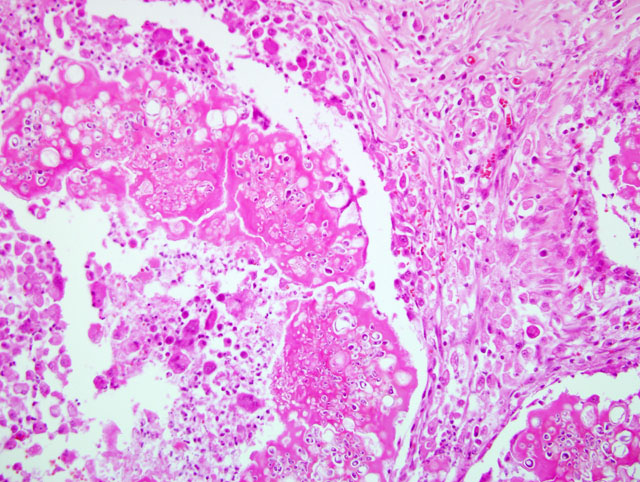

The pathognomonic histologic lesion is the presence, deep in the dermis and subcutis, of aggregates of compact mycelia within a granulomatous tissue reaction. The fungi may be surrounded by amorphous eosinophilic material representing the Splendore-Hoeppli reaction. The overlying skin may show parasitized shafts in the absence of inflammation or the more typical folliculitis. Fungi in the superficial lesions have normal morphology. Invasion of hyphae through the external root sheath has been described.(11) Cytology is useful for making diagnosis of mycetomas in humans, but it can be difficult to perform.(9) A cytological diagnosis of pseudomycetoma should be suspected and is warranted if arthrospores and refractile septate hyphae are present in cytologic specimens from Persian cats with single or multiple dermal nodules, especially if pyogranulomatous inflammation is also present.(2)

Fungal culture represents by far the most reliable diagnostic evidence to ascertain the aetiological agent of these infections.(7) Microsporum canis is isolated in most cases, but colonies do not always have a typical appearance on primary cultures, and macroconidia are often lacking. Molecular tools have been used on histological sections for identification of dermatophytic mycetomas.(2) PCR seems to be a reliable and useful complementary method to identify the aetiological fungus from paraffin-embedded sections obtained from cases of dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in different animal species. Molecular biology could be a valid alternative identification method when 1) culture is unsuccessful; 2) in retrospective analysis, when only a stored histological section is available; 3) and in further studies on the aetiologic agents of Dermatophytic pseudomycetoma from biopsy confirmed pathological specimens.(7)

Differential diagnosis with nodulous tumoral diseases is necessary, and a dermatophytic origin would be suspected for all pseudo-tumoral masses observed on feline skin (2) and, especially in Persian cats, when poorly marginated intraabdominal mass were detected on imaging examinations.(9)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Facial dermatitis of Persian and Himalayan cats is an uncommon, idiopathic facial dermatitis that causes a matting of the facial hair by dark, greasy sebaceous material in young cats.(3) Chediak-Higashi syndrome is an autosomal recessive condition that is reported most commonly in humans, cattle, Persian cats, beige mice, rats and Aleutian mink.(10) Affected animals have a defective LYST/CHS1 gene that regulates intracellular protein trafficking and vesicle fusion.(5) This defect causes enlarged granules in melanosomes, granulocytes and platelets which results in color dilution, bleeding tendencies and recurrent infections.(10)

References:

2. Chermette R, Ferreiro L, Guillot J: Dermatophytoses in Animals. Mycopathologia doi:10.1007/s11046- 008-9102-7, 2008.

3. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK: Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed., pp. 112-115. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, Iowa, 2005

4. Kano R, Edamura K, Yumikura H, Maruyama H, Asano K, Tanaka S, Hasegawa A: Confirmed case of feline mycetoma due to Microsporum canis. Mycoses, doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01518.x, Apr 26, 2008

5. Kaplen J, De Domenico I, Ward DM: Chediak-Higashi syndrome. Curr Opin Hematol 15:22-29, 2008

6. Maxie MG, Youssef S: Nervous system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 326-327. Elsevier, Edinburgh, UK, 2007

7. Nardoni S, Franceschi A, Mancianti F: Identification of Microsporum canis from dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in paraffin-embedded veterinary specimens using a common PCR protocol. Mycoses 50:215217, 2007

8. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, p. 302. Elsevier, Edinburgh, UK, 2007

9. Stanley SW, Fischetti AJ, Jensen HE: Imaging diagnosis-sublumbar pseudomycetoma in a Persian cat. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 49:176178, 2008

10. Valli VEO: Hematopoietic system. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 3, p. 115. Elsevier, Edinburgh, UK, 2007

11. Yager JA, Scott DW: The skin and appendages. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, eds. Jubb K.V.F., Kennedy P.C & Palmer N., 4th ed., vol. 1, pp. 707-718. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 1993.