Signalment:

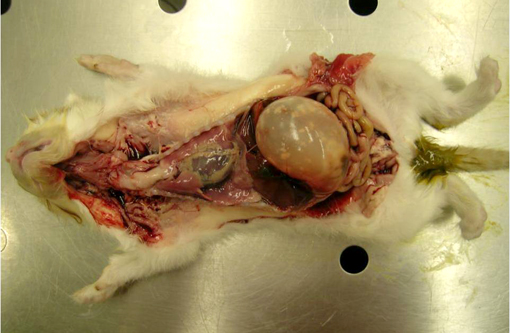

Gross Description:

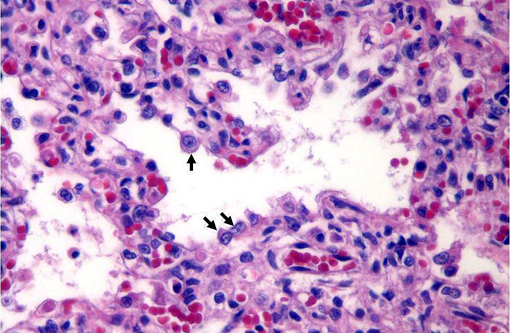

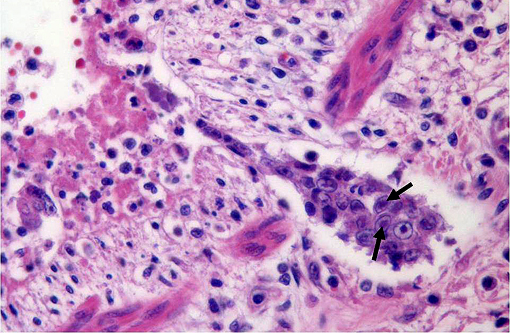

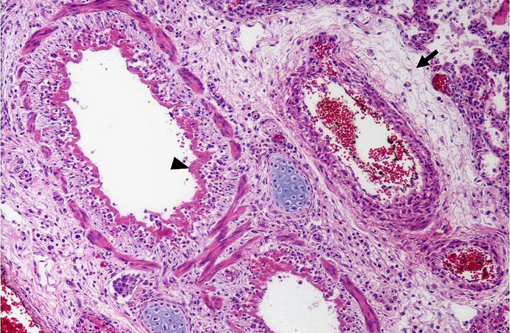

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) is an alphaherpesvirus (genus Varicellovirus) that infects members of the family Felidae. The virus is antigenically and genetically similar to canine herpesvirus-1 and phocine herpesvirus-1. Infection is typically the result of direct contact, but environmental transmission is also reported. Although experimental studies have produced transplacental infection of kittens, natural in utero transmission has not been documented. Viral replication primarily occurs in the nasal cavity, tonsils, and pharynx. Viremia is rare, presumably because the virus replicates best at low body temperatures. The virus typically infects respiratory epithelial cells and causes necrosis, fibrin exudation and neutrophilic infiltration. Intranuclear inclusion bodies are commonly seen during the acute phase of infection.Â

FHV-1 causes upper respiratory tract disease, characterized by sneezing, inappetence, fever, conjunctivitis, ocular and nasal discharge. Primary FHV-1 pneumonia is uncommon, and usually seen only in young or debilitated animals. Neurological signs, abortion, osteolytic lesions in the nasal turbinates and skin ulcers, particularly in cheetahs3 have also been reported with FHV-1 infections. Following acute disease, the virus can enter a latent phase, most likely in the trigeminal ganglion,(4) with periodic reactivation in times of stress.Â

Feline calicivirus (FCV) is another important cause of respiratory disease in cats. Like FHV-1, FCV can cause pneumonia, but is more commonly associated with upper respiratory tract disease. FCV infected cats are more likely to have oral ulceration, and less likely to have ocular lesions, compared to FHV-1 infected cats. Co-infections with FHV-1 and FCV are not uncommon. In a study of cats from eight animal shelters, the prevalence of FCV ranged from 13 to 26% and the prevalence of FHV-1 varied between 3 and 38%.(1) Recently, a FCV-associated virulent systemic disease (VSD) has been described, which, in addition to upper respiratory tract disease, is characterized by cutaneous edema, ulcerative dermatitis, and jaundice.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

This particular case is an example of a bronchointerstitial pneumonia because of the presence of bronchiolar epithelial necrosis as well as alveolar damage. Common causes of bronchointerstitial pneumonia are airborne viruses or toxins which damage both Clara cells and type II pneumocytes. Bronchointerstitial pneumonia is a form of interstitial pneumonia characterized by inflammation of alveolar or interlobular septa. In contrast, bronchitis and bronchiolitis involve only the airways, and bronchopneumonia is characterized by leukocytic exudates which fill bronchioles and alveoli but lacking significant bronchiolar or alveolar septal involvement (2). Feline herpesvirus-1, an alphaherpesvirus, causes significant necrosis, neutrophilic inflammation and the elaboration of fibrin.Â

Bronchial glands are prominent in the cat lung but absent in most other domestic species. Microscopic evaluation of the lungs of felids should always include scrutiny of the bronchial glands because glandular epithelial necrosis and herpesviral inclusions are often readily apparent in these structures.Â

References:

2. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed., vol. 2, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007: 561-7.Â

3. Munson L, Wack R, Duncan M, Montali RJ, Boon D, Stalis I, Crawshaw GJ, Cameron KN, Mortenson J, Citino S, Zuba J, Junge RE: Chronic eosinophilic dermatitis associated with persistent feline herpes virus infection in cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Vet Pathol 41:170-176, 2004

4. Pesavento PA, MacLachlan NJ, Dillard-Telm L, Grant CK, Hurley K: Pathologic, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic findings in naturally occurring virulent systemic feline calicivirus infection in cats. Vet Pathol 41(3):257-63, 2004

5. Townsend WM, Stiles J, Guptill-Yoran L, Krohne SG: Development of a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay to detect feline herpesvirus-1 latency-associated transcripts in the trigeminal ganglia and corneas of cats that did not have clinical signs of ocular disease. Am J Vet Res 65:314-319, 2004