CASE 4: 18-2823-3 (4138049-00)

Signalment:

15-year-old Thoroughbred gelding

History:

The patient presented to NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine for evaluation by the Equine Orthopedic Surgery Service and Dermatology Service for a 2.5-month history of right hind limb lameness and chronic pastern dermatitis. Based on radiographs and ultrasound of the right hind limb, the referring veterinarian diagnosed annular ligament desmitis, but following treatment with stall rest, hand-walking, trazodone, and acepromazine, the horse showed no improvement and became increasingly difficult to manage on stall rest. The pastern dermatitis was treated chronically with a variety of medications including flunixin meglumine, cetirizine, and enrofloxacin. The swelling in his distal limbs increased while on stall rest. Physical exam identified marked thickening and effusion of the right hind digital flexor tendon sheath and annular ligament constriction, as well as evidence of cellulitis with chronic crusting and ulcers over the pastern region of both hind limbs (left > right). Ultrasound of the right hind distal limb identified a tear of the manica flexoria, superficial digital flexor tendon, and possibly deep digital flexor tendon. Surgery to further evaluate the tendon injury was recommended but given the need for aggressive management of the dermatitis prior to surgery and the suspected prolonged rehabilitation time with an uncertain prognosis for recovery, euthanasia was elected.

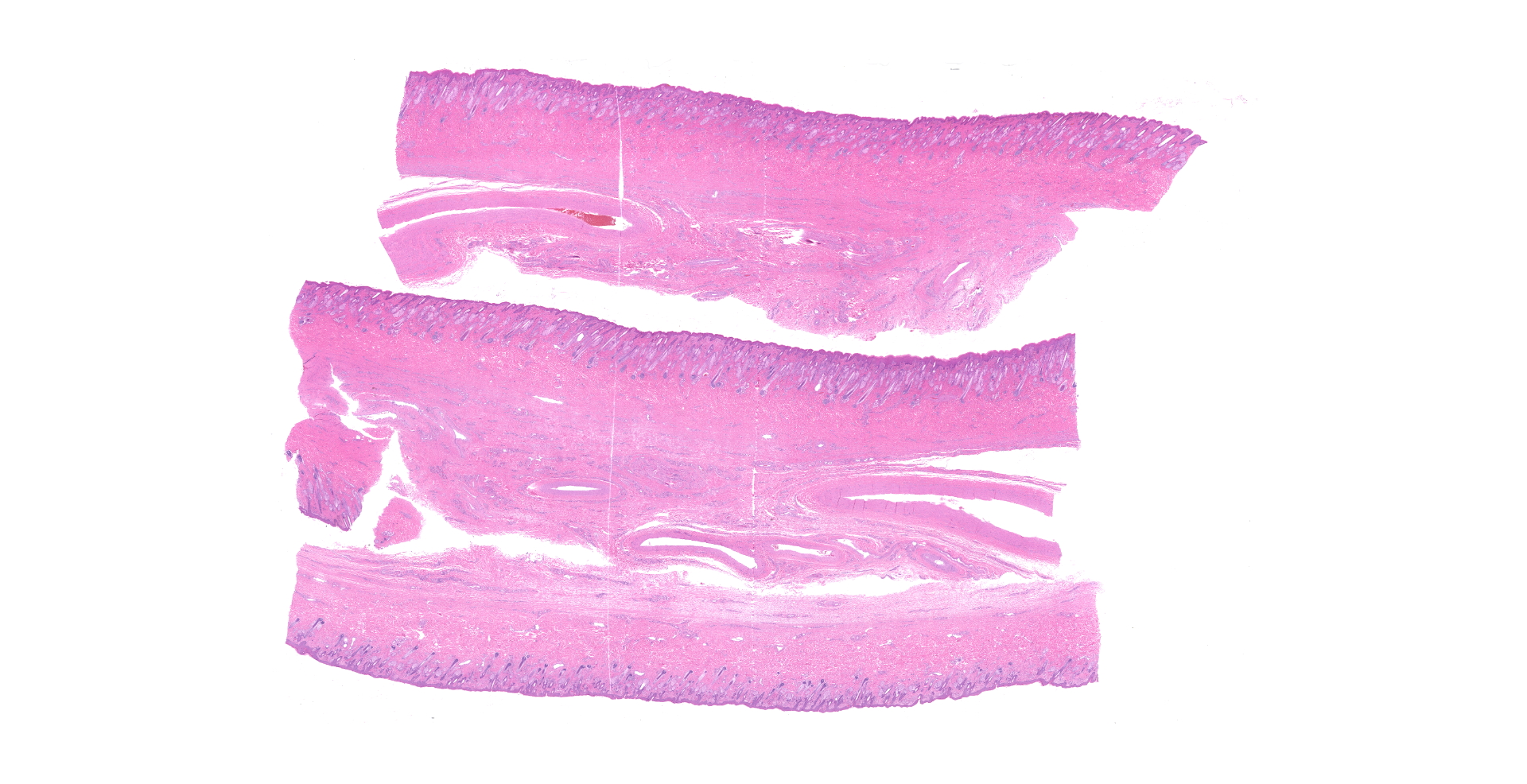

Gross Pathology:

Submitted for autopsy is a 15-year-old Thoroughbred gelding of unreported weight. The body is in good postmortem condition (euthanasia to autopsy interval of approximately 15 hours) with minimal autolysis and dehydration. On both hind limbs, the plantar and lateral aspects of the fetlock and pastern (which were circumferentially non-pigmented) show mild to moderate, multifocal, fairly well-demarcated regions of erythema and edema with multifocal areas of alopecia. Additionally, on both hind limbs just proximal to the coronary band circumferentially are 5-8, multifocal, up to 1.5 cm in diameter ulcers overlain by serous crusts (see gross photo). Just proximal to the fetlock joint, the distal right hind limb has mild, regional thickening of all ligamentous structures, and the overlying soft tissues are expanded by soft tissue swelling and subcutaneous edema. In this region, the lateral manica flexoria has a 4 mm in length tear, and the associated portion of manica flexoria and superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) are mildly thickened. Deep to the manica flexoria, the distolateral deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) is moderately thickened with edema and mild erythema, and along the lateral margin is a roughened, markedly erythematous surface overlain by fibrinous material. Within the flexor tendon sheath there are additional loose coagula of soft, fibrinous material.

Laboratory results:

No additional testing

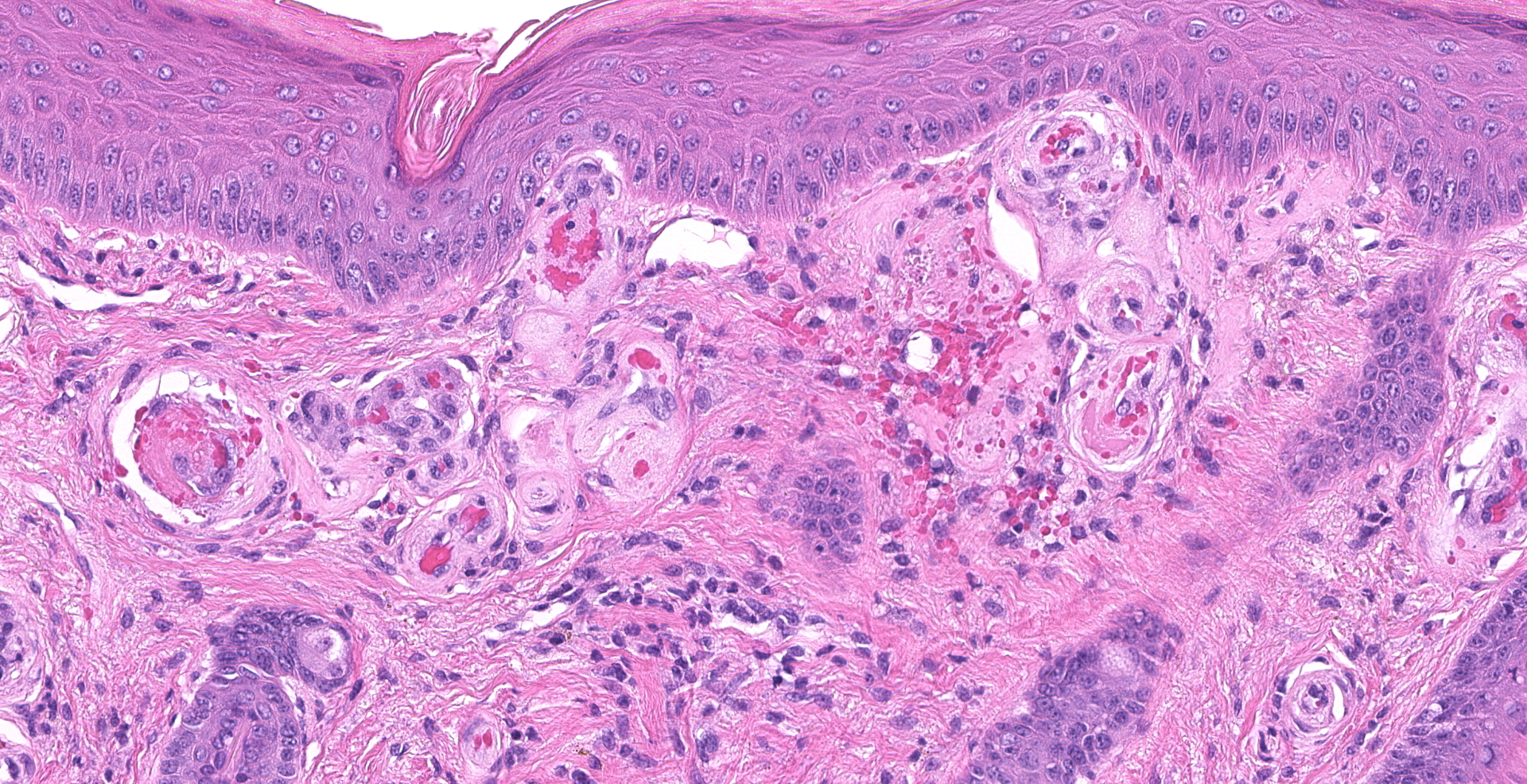

Microscopic description:

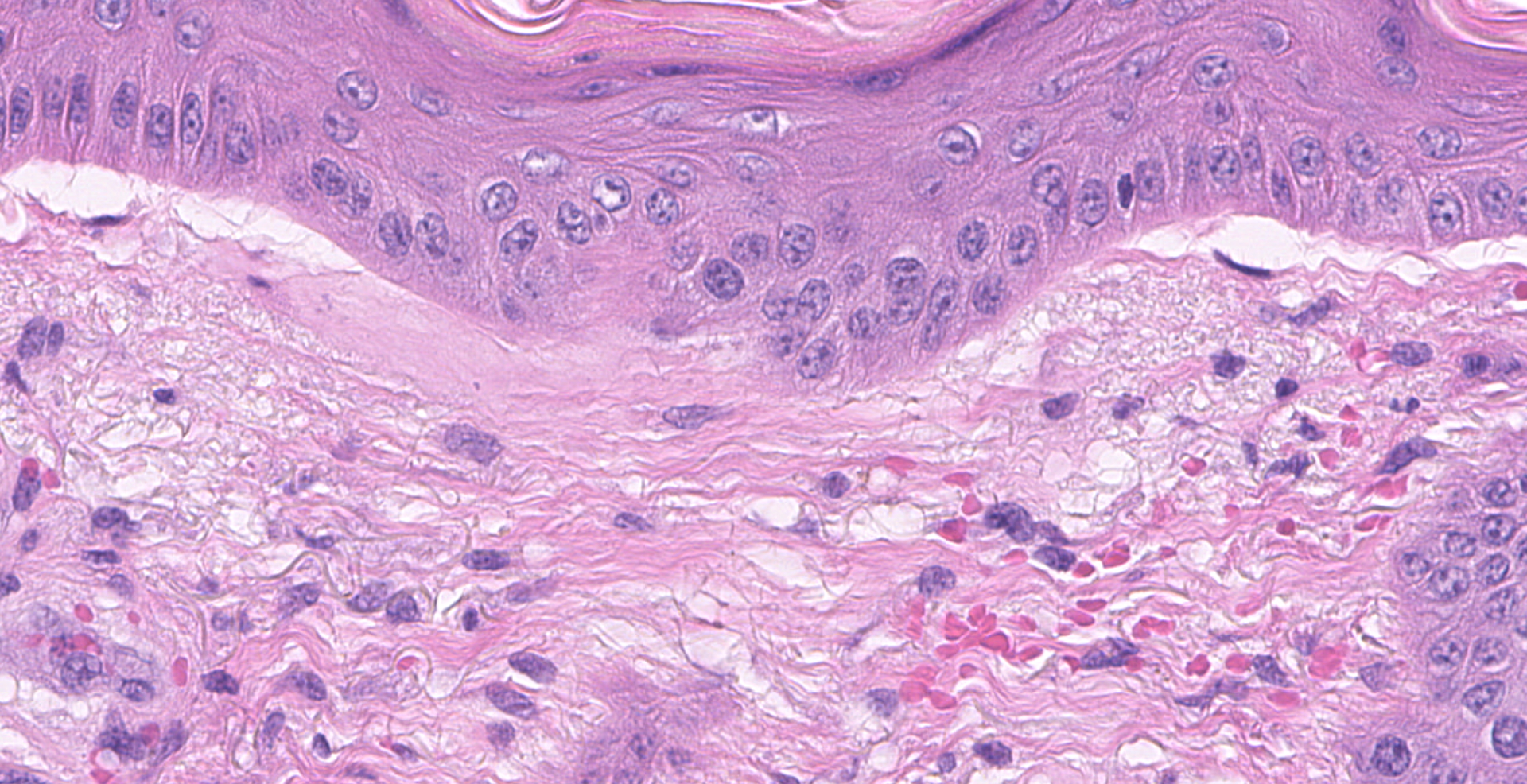

Haired skin (right pastern): The superficial dermis is mildly expanded by increased clear space (edema) and frequently has dilated small caliber vessels that are multifocally increased in number. These superficial small caliber vessels multifocally have walls thickened and replaced by hyalinized eosinophilic material (fibrinoid vascular necrosis) with an occasional dusting of karyorrhectic cellular debris and rare neutrophils within the vessel wall (leukocytoclastic vasculitis). There are occasional microhemorrhages into the wall and adjacent interstitium. In occasional affected vessels, the lumina are completely occluded by coagula of homogenous eosinophilic material (fibrin microthrombi). In intact vessels, endothelial cells are frequently hypertrophied. Occasionally within superficial and mid-dermal vessels, the vessel wall is pale, eosinophilic and distorted (hyalinosis). The epithelium is mildly thickened with occasional mild orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. The superficial dermis has minimal, multifocal to coalescing, perivascular to interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells. There is occasional follicular ectasia. The superficial dermis multifocally has prominent elastin fibers (elastosis).

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Haired skin of the right pastern:

- Moderate to marked, multifocal, superficial arteriolar fibrinoid vascular necrosis with microhemorrhages, fibrin microthrombi, and hyalinosis

- Moderate (solar) dermal elastosis

Contributor's comment:

Pastern leukocytoclastic vasculitis, also called photoaggravated vasculitis or photoactivated vasculitis, is a disease of cutaneous vasculitis unique to horses that typically affects nonpigmented skin of the distal limbs and occasionally the muzzle.2 Gross cutaneous changes include crusts, erosions to ulcerations, and edema, and the condition can be quite painful.2 Because the pastern is typically affected, other causes of equine pastern dermatitis must be ruled out and include primary irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, pastern folliculitis/pyoderma (due to infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Dermatophilus congolensis), chorioptic mange, dermatophytosis, Malassezia infection, immune-mediated dermatitis (such as pemphigus foliaceus), and neoplastic conditions (such as sarcoidosis).1 Pastern leukocytoclastic vasculitis most often affects adult horses, and there does not appear to be a sex predisposition.5,6 Lesions are typically bilaterally symmetrical but can be confined to just one limb, even if other limbs have non-pigmented regions, and lateral and medial aspects of the distal limbs are most often affected with hind limbs affected more often than the forelimbs.2,5 Histological findings are similar to those in this case and include dermal edema, vascular dilation and intramural inflammatory cells, leukocytoclasia with nuclear dust, microhemorrhages, and thickening of the vessel wall of the small superficial, mid, and deep dermal vessels.5 Secondary bacterial infections are common.5 Uncommonly, chronic cases can develop marked, papillary epidermal hyperplasia that develops a verrucous appearance.2

The pathogenesis of this syndrome is poorly understood, and it is thought to be immune-mediated.2 Because the changes tend to occur on non-pigmented skin, UV radiation is thought to be involved in inducing vasculitis.2 However, the support for this is variable among studies with some studies suggesting that UV radiation is likely only a minor contributor.5,6 Photosensitization has been suggested as the underlying cause, but there is no evidence of hepatic insufficiency nor known exposure to photosensitizing compounds. Additionally, lesions often do not affect the entirety of the nonpigmented skin as other photosensitizing conditions do, and pigmented skin can also be involved though usually to a lesser degree.5 Other causes of cutaneous vasculitis are not present in these cases because there is no history of trauma nor vasculitis-associated infectious agents such as Staphylococcus spp. or dermatophilosis.2,5 In the present case, the solar elastosis supports the contribution of UV exposure to disease development, and there is evidence (predominantly in other sections not included in the submitted slide) for bacterial infection that was likely secondary rather than causal given the presence of vasculitis in areas without evidence for infection. Thus, the etiology of photoaggravated vasculitis remains unclear, making treatment of the condition challenging and often unsuccessful.5,6

Cutaneous vasculitis is most common in the horse and dog and is considered rare in most other species such as cats, pigs, and cattle.2 Other forms of cutaneous vasculitis in the horse include purpura hemorrhagica (leukocytoclastic vasculitis induced by Streptococcus equi subspecies equi and leading to hemorrhages and extensive edema) and nodular eosinophilic vasculitis (nodular to linear lesions that are firm and painful on one or more legs).2,3 In the dog, causes of cutaneous vasculitis are varied and complex and may be associated with hypersensitivity reactions (type I, II, or III), infectious agents, neoplasia, drugs, or toxin exposure.2 A classic example is infection with the endotheliotropic Rickettsia rickettsii. Familial or inherited forms of vasculitis have also been documented. In pigs, cutaneous vasculitis is most commonly associated with Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. Additionally, porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome, associated with porcine circovirus 2, results in systemic vasculitis primarily affecting the skin and kidneys.2

Contributing Institution:

Submitted by NIH Comparative Biomedical Scientist Training Program (CBSTP)

https://nih-cbstp.nci.nih.gov/

Case materials from: North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Population Health and Pathobiology

JPC diagnosis:

Haired skin, superficial dermis: Vasculitis, necrotizing, diffuse, marked, with mild solar elastosis.

JPC comment:

The contributor summarized much of what is currently understood about this disease. While a direct causal link to bacterial infection has not yet been established, in some reported cases, Staphylococcus intermedius, coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. pseudintermedius, S. aureus, Proteus spp, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been isolated at affected sites. In a recently reported case, a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MRPA) was cultured from a deep skin biopsy. Following three weeks' treatment with oral enrofloxacin and topical chlorhexidine shampoo cleaning, the skin lesions had healed, and hair was regrowing.4

This reported case highlights the dearth of knowledge about pathogenesis of this disease. While it is biologically plausible that certain bacteria cause type III hypersensitivity induced vasculitis, identification of a causative bacterium is inconsistent. It is also difficult to discount the predilection for non-pigmented skin, though there can be less severe manifestations in pigmented skin. From the sparse case data accumulated to date, it seems likely that disease progression is multifactorial, perhaps with both an immune complex vasculitis component, as well as a component of photosensitization.

References:

- Anthony AY. Equine pastern dermatitis. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2013;29(3), 577-588.

- Maudlin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 580, 611-612.

- Morris DD. Cutaneous vasculitis in horses: 19 cases (1978-1985). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1987;191(4), 460-464.

- Panzuti P, Ferrer GR, Mosca M, Pin D. Equine pastern vasculitis in a horse associated with a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate. Vet Dermatol. 2020;31(3):247-e55.

- Psalla D, Rüfenacht S, Stoffel MH, et al. Equine pastern vasculitis: A clinical and histopathological study. Vet J. 2013;198(2), 524-530.

- White SD, Affolter VK, Dewey J, Kass PH, Outerbridge C, Ihrke PJ. Cutaneous vasculitis in equines: a retrospective study of 72 cases. Vet Dermatol. 2009;20(5?6), 600-606.