Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 11

December 6th, 2017

CASE I: SQ (JPC 4048071).

Signalment: Adult, female, eastern fox squirrel, Sciurus niger, squirrel.

History: This squirrel was found being bitten by a dog. The squirrel died after extrication and the dog’s owner presented the squirrel for necropsy due to its unusual external appearance.

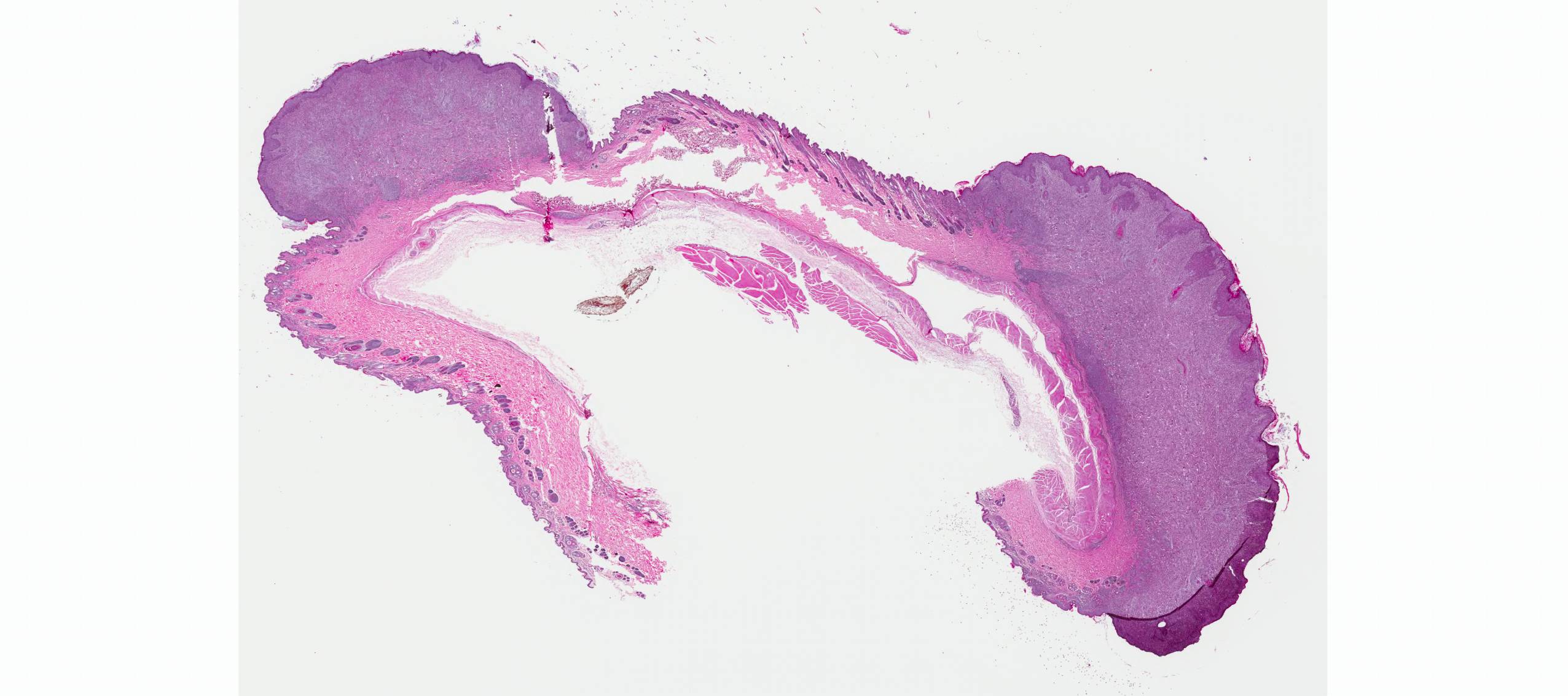

Gross Pathology: Distributed throughout the skin, there were numerous (approximately 100), well-demarcated, ovoid to circular, raised nodules ranging from approximately 3 to 35 mm in diameter. The nodules were alopecic, tan to gray, and irregularly smooth surfaced, to variably eroded and ulcerated. On cut section, the nodules consisted of white to tan proliferative soft tissue expanding the dermis. The palpebral fissure of the right eye was narrowed by nodular expansion of the upper eyelid.

The thoracic cavity was filled with blood (hemothorax) and the right thoracic wall had two penetrating, blood-rimmed, tracts (dog bite wounds).

Laboratory results:

PCR using primers targeting the poxviral DNA polymerase and subsequent sequencing had 99% identity with GenBank squirrel fibroma virus isolates.

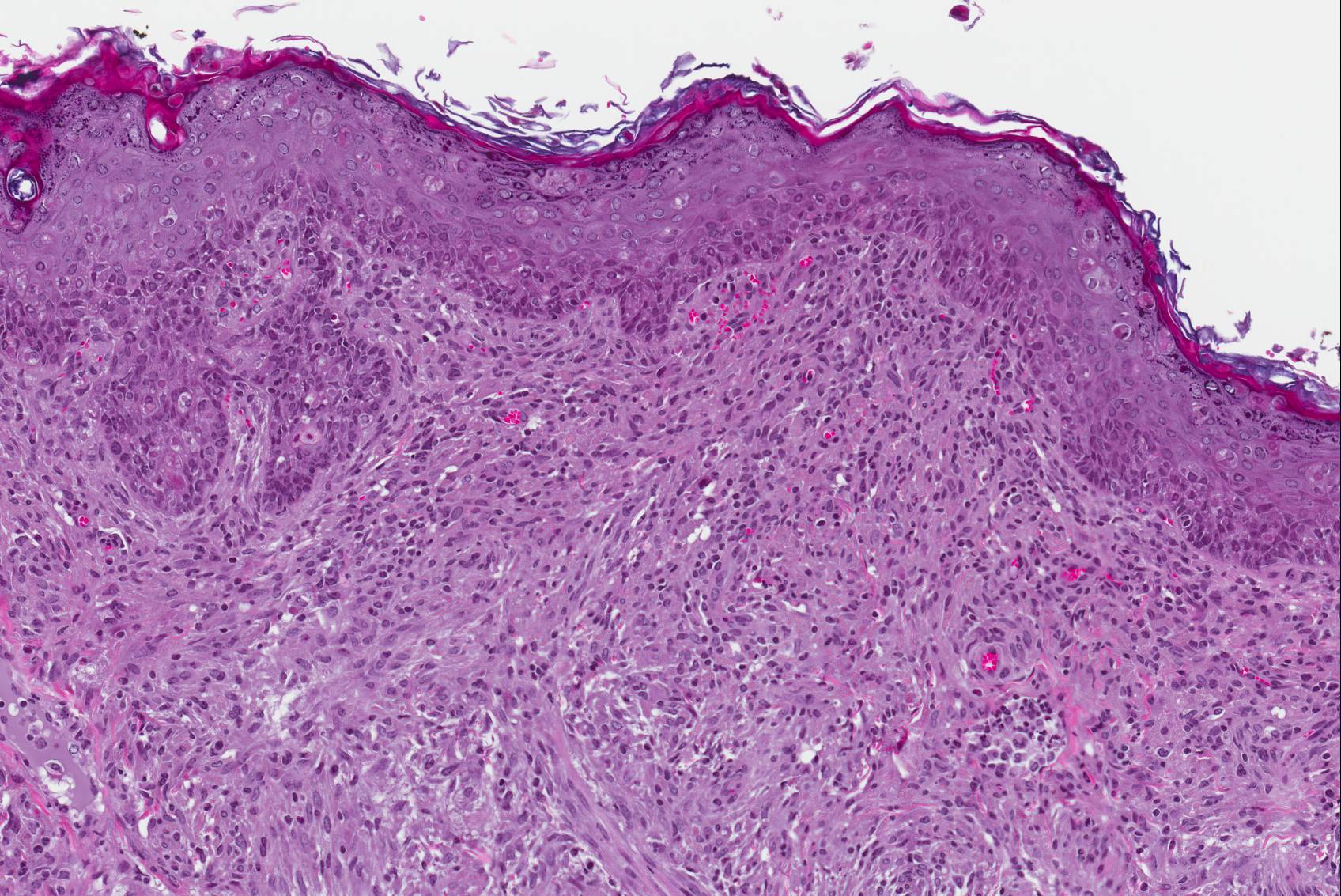

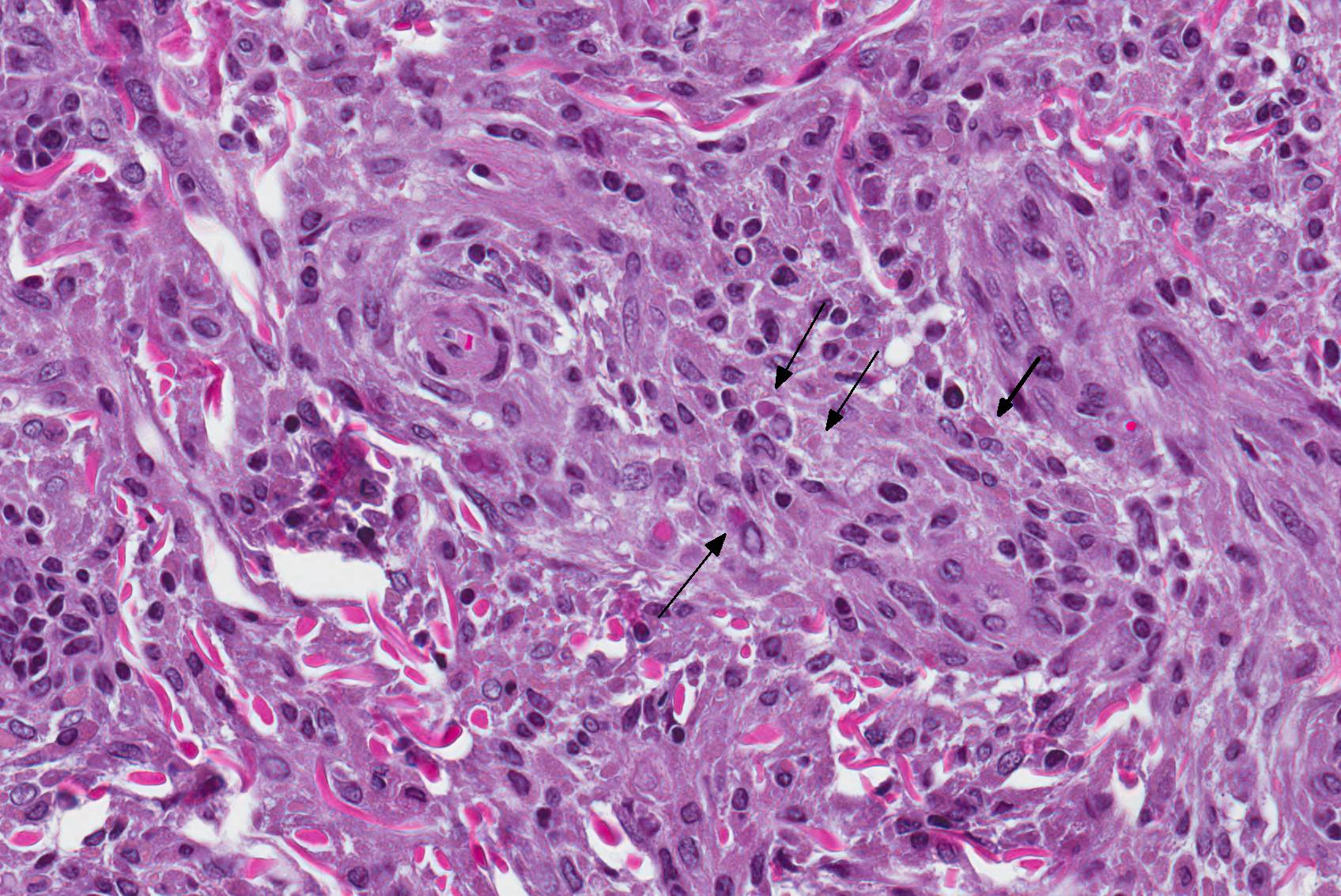

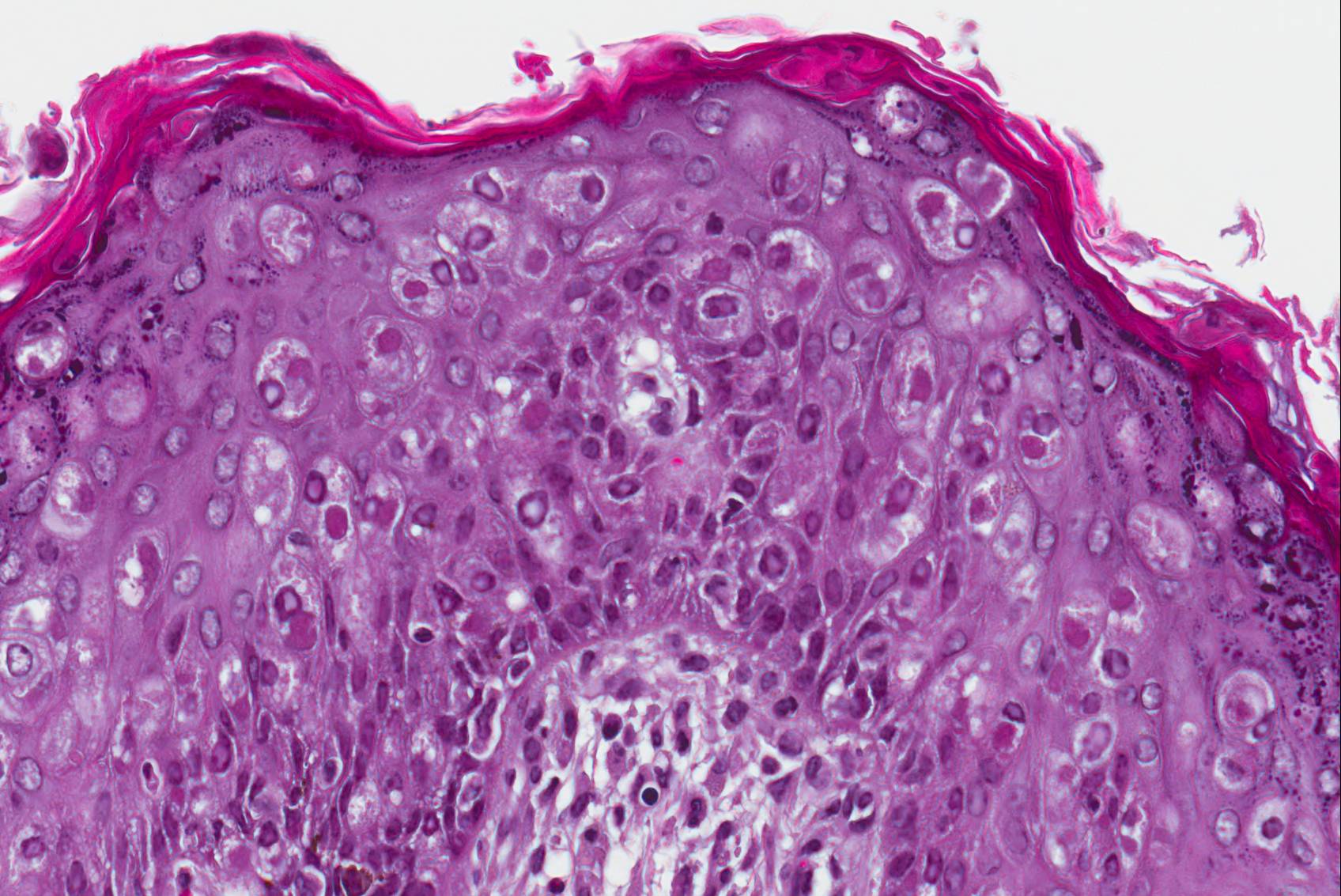

Microscopic Description: Haired skin: The cutaneous nodular lesions were fairly well-demarcated, broad-based, and raised, consisting of nonencapsulated proliferations of spindloid mesenchymal cells expanding and mildly infiltrating the superficial to deep dermis, with regionally moderate epidermal and follicular epithelial hyperplasia. The epidermis had prominent acanthosis, mild irregular granulosis, and mild laminar orthokeratosis, as well as low numbers of multifocally desquamating devitalized superficial keratinocytes. Some sections had mild multifocal superficial erosion associated with focal parakeratosis and serocellular crusting, and other sections (not submitted) had regionally extensive ulceration with dense surface crusting and interspersed coccoid bacteria. Moderate numbers of individualized keratinocytes, mainly in the stratum spinosum, had prominent cytoplasmic swelling and pallor (hydropic change, ballooning degeneration), and some of these keratinocytes also contained single to multiple variably sized, eosinophilic, globular cytoplasmic poxviral inclusions (approximately 8 to 20 micrometers in diameter). The proliferative spindloid cells were arranged in dense, interweaving, bundles amidst fine collagenous supporting stroma. These cells had small to moderate quantities of eosinophilic cytoplasm, indistinct cell borders, ovoid nuclei, finely stippled chromatin, and 1 to 2, small, indistinct nucleoli. Low to moderate numbers of the cells contained smaller (approximately 6-12 micrometer diameter), paler eosinophilic, cytoplasmic viral inclusions. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were mild to moderate, and mitotic cells were rare. Low to moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells were mixed with the dermal mesenchymal cell proliferation, especially at the deep margin, where they extended perivascularly into the adjacent dermis and hypodermis. In some regions, the superficial dermis also contained few interspersed neutrophils, free erythrocytes (hemorrhage), and scattered shrunken cells with pyknotic and karyorrhectic nuclei.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Multifocal dermal fibromas, with moderate epidermal hyperplasia, ballooning degeneration, intraepithelial and intramesenchymal cell cytoplasmic poxviral inclusions, and mild lymphoplasmacytic dermatitis.

Contributor’s Comment: Squirrel fibromatosis results from infection by squirrel fibroma virus, a poxvirus in the Leporipoxvirus genus, closely related to rabbit fibroma virus. The disease has been reported in North American eastern gray, western gray, red, and fox squirrels, and is generally sporadic in occurrence, with rare epizootics.1 The gross lesions are considerably distinctive, consisting of single to multiple, alopecic, dermal soft tissue nodules that often occur on the face, trunk, limbs, and genital region.1,9 Involvement of the eyelids has been reported as a common finding9 (as in Image 1), and nodular lesions in internal organs are less common.1,7

Histologically, cutaneous squirrel fibromatosis lesions consist of a combination of typical poxviral epidermal changes and underlying dermal mesenchymal fibroblast-like cell proliferation.1,9 The epidermal changes are characterized by epithelial hyperplasia, keratinocyte ballooning changes, and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic poxviral inclusions. The proliferative dermal spindle cells have mild cellular pleomorphism and fewer, smaller, intracytoplasmic viral inclusions. Mixed dermal inflammation (consisting of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages), as well as epidermal erosion, ulceration, and crusting are variable.1,9 In fewer cases, widespread mesenchymal and epithelial proliferations with intracytoplasmic viral inclusions have also been reported to occur at extracutaneous sites, including the lungs, liver, kidney, and lymph nodes.1,7

The cutaneous lesions of squirrel fibromatosis are reported to often regress spontaneously, but mortality can occur with debilitation and/or systemic disease. Immunocompetence may play a role in disease susceptibility and the severity of lesions.1,9 Routes of viral transmission are thought to include biting insects and direct contact, and multifocal lesions may arise from viremia and/or additive cutaneous exposures.1,9

Other species-selective poxviral infections of tree squirrels are squirrelpox virus (also previously termed “squirrel parapoxvirus”) and the newly described Canadian squirrelpox virus.1,2,5 In contrast to squirrel fibromatosis, the squirrelpox diseases are characterized by exudative and ulcerative dermatitis lacking nodular dermal mesenchymal proliferations. Furthermore, the squirrelpox diseases have a fatal clinical course (albeit the Canadian disease is limited to a single case report), and the causative poxviruses are distinct from the currently named poxviral genera.1,2,3,5 Although serologic findings support exposure of North American eastern gray squirrels to the squirrelpox virus of the United Kingdom/Ireland, the gray squirrels do not develop clinical disease. Evidence suggests that the virus was introduced to the UK with the eastern gray squirrels and it now threatens the survival of European red squirrels.4,5

Table 1. Relevant details of squirrel-selective poxviral infections1,2,3,5

|

Disease Name |

Virus (Viral Genus) |

Main Host(s) [Geography] |

Clinical Outcome |

Gross Lesions |

Histologic Features |

|

Squirrel fibromatosis (SQFV) |

Squirrel fibroma virus [Leporipoxvirus] |

Eastern gray squirrels, also western gray, red, and fox squirrels [Eastern North America] |

Lesions often regress, occasional mortality |

Cutaneous and lesser visceral nodules |

Epithelial hyperplasia and mesenchymal (fibroblast) proliferation; ballooning keratinocyte degeneration; ICIB in proliferative epithelial and mesenchymal cells |

|

Squirrelpox (SQPV)

|

UK squirrelpox virus [Novel genus within chordopoxvirinae, not yet named] |

European red squirrel (Gray squirrels clinically resistant) [United Kingdom and Ireland] |

Fatal |

Exudative dermatitis |

Epidermal hyperplasia with ulceration, crusting, and necrsuppurative dermatitis; ballooning degeneration and ICIB in keratinocytes |

|

Canadian squirrelpox virus [unassigned, most closely related to parapoxviruses] |

North American red squirrel (only 1 case) [Canada, Yukon territory] |

Fatal |

Exudative dermatitis (more like SQPV than SQFV) |

(As above for SQPV) [more like SQPV than SQFV; virus identified only in epithelial cells] |

Poxviruses are enveloped DNA viruses that are prominently epitheliotropic and commonly induce epithelial hyperplasia (acanthosis), epithelial cell swelling (ballooning degeneration), and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies. Grossly, the archetypal cutaneous lesions progress through macule, papule, vesicle, pustule, crust and scar phases.11 Ultrastructurally, poxviral particules are brick-shaped, enveloped, smooth-surfaced, electron-dense virions (approximately 200-300 nm), with a biconcave (dumb-bell shaped) nucleocapsid core and adjacent lateral bodies.1 The family Poxviridae is classified into two subfamilies: Entomopoxvirinae, which infect insects, and Chordopoxvirinae, which infect a wide range of vertebrates. Poxviruses that induce cutaneous tumors include squirrel fibroma virus, rabbit fibroma virus, rabbit myxoma virus, yaba monkey tumor virus, lumpy skin disease virus, and sheeppox virus.

Table 2. Chordopoxvirinae genera, major viruses, and some notable features11,JPC archives

|

Genus |

Major Viruses |

|

Avipoxvirus |

Fowlpox virus, Canarypox virus, Pigeonpox virus, Quailpox virus, Turkeypox virus - Characteristic histologic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies: “Bollinger bodies” |

|

Capripoxvirus |

Sheeppox virus, Goatpox virus, Lumpy skin disease virus - All cause systemic disease, mortality/economic loss can be high, especially with sheeppox - “Sheeppox cells” accumulate in lesions: mononuclear cells (macrophages/monocytes, fibroblasts) with vacuolated nuclei/marginated chromatin and ICIB |

|

Cervidpoxvirus |

Deerpox virus |

|

Crocodylidpoxvirus |

Nile crocodilepox virus |

|

Leporipoxvirus |

Rabbit (Shope) fibroma virus, Rabbit myxoma virus, Squirrel fibroma virus - Rabbit (Shope) fibroma virus: causes rabbit fibromatosis (like squirrel fibroma virus) o Atypical dermal mesenchymal proliferation, epidermal hyperplasia, ballooning degeneration, ICIB in epithelium and mesenchymal cells o Benign, self-limiting disease - Rabbit myxoma virus: causes cutaneous myxomatosis (“bighead”) o Atypical myxomatous mesenchymal proliferation, epidermal hyperplasia, ballooning degeneration, ICIB in epithelial cells only o Local/benign lesion in American rabbits, but systemic/severe in European rabbits |

|

Molluscipoxvirus |

Molluscum contagiosum virus - Infects horses, donkeys, kangaroos, etc.; large ICIB: “molluscum bodies” |

|

Orthopoxvirus |

Cowpox virus, Ectromelia (mousepox) virus, Monkeypox virus, Rabbitpox virus, Horsepox virus, Camelpox virus, Vaccinia virus, Variola (smallpox) virus - Cowpox virus: teat/udder lesions in cows, but not common; infects others including cats - Monkeypox virus: systemic disease in monkeys and rodents - Ectromelia virus: also causes splenic and hepatic necrosis o A-type inclusions (Marchal bodies): eosinophilic, occur late in disease, common in epidermis (not liver) o B-type inclusions (Guarnieri bodies): basophilic, occur early in disease, present in all infected cells - Rabbitpox: only been reported in laboratory populations - Vaccinia virus: used in vaccines to eradicate smallpox; no disease in domestic animals |

|

Parapoxvirus |

Ovine parapoxvirus (contagious ecthyma, contagious pustular dermatitis, Orf, sore mouth), Pseudocowpox virus, Bovine popular stomatitis virus - Ovine parapoxvirus: sheep, goats, cattle, less commonly others; zoonotic o Inclusions only briefly detected in vesicular stage - Pseudocowpox virus: lesions in milking cows, zoonotic to humans: “Milker’s nodules” - Bovine popular stomatitis virus: lesions more often mouth/muzzle, transmission to humans looks comparable to “milker’s nodules” |

|

Suipoxvirus |

Swinepox virus - Host specific, sucking louse (Haematopinus suis) contributes to mechanical transmission |

|

Yatapoxvirus |

Yaba monkey tumor virus, Tanapox virus - Yabapoxviral dermatitis: benign, dermal tumor, regress; previously termed “histiocytomas”; ICIB in proliferating dermal mesenchymal cells - Tanapox virus: causes “benign epidermal monkey pox”; ICIB in keratinocytes |

JPC Diagnosis: Haired skin: Viral fibropapillomas, multiple, eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger), squirrel.

Conference Comment: Squirrel fibroma virus belongs to the Leporipoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family of viruses and is related to rabbit (shope) fibroma virus and rabbit myxoma virus. The different poxvirus genera are concisely described by the contributor above. Of historical interest, Richard Edwin Shope was an American virologist and physician who identified Shope papillomavirus in 1933 which was the first human virus discovered6. This discovery assisted later researchers in linking papillomaviruses to warts and cervical cancer8. Among other pathologies, he identified Influenzavirus A in pigs (1931) and cultured it from a human in 1933 later identifying it as the virus that circulated in the 1918 pandemic10. Interestingly, his son, Robert Shope, was also a virologist that specialized in arthropod-borne viruses6.

As is always the case when leporipox-driven entities appear in the Wednesday Slide Conference, vigorous debate surrounded the morphologic diagnosis. Emboldened by the recent identification of the neoplastic cells within the dermis as fibroblasts12, the staff of the Joint Pathology Center threw off the yoke of conservatism exemplified by its longstanding diagnosis of "atypical mesenchymal hyperplasia" and, noting the presence of viral inclusions in both the epidermis and dermis, unanimously endorsed that of "viral fibropapilloma".

Contributing Institution:

Michigan State University

Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health

References:

- Bangari DS, Miller MA, Stevenson GW, Thacker HL, Sharma A, and Mittal SK. Cutaneous and systemic poxviral disease in red (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) and gray (Sciurus carolinensis) Vet Pathol 2009;46:667-672.

- Himsworth CG, McInnes CJ, Coulter L, Everest DJ, and Hill JE. Characterization of a novel poxvirus in a North American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus). J Wildl Dis 2013;49:173-179.

- Himsworth CG, Musil KM, Bryan L, and Hill JE. Poxviral infection in an American Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) from northwestern Canada. J Wildl Dis 2009;45:1143-1149.

- McInnes CJ, Counter L, Dagleish MP, Daene D, Gilray J, Percival A, Willoughby K, Scantlebury M, Marks N, Graham D, Everest DJ, McGoldrick M, Rochford J, McKay F, and Sainsbury AW. The emergence of squirrelpox in Ireland. Anim Conserv 2013;16:51-59.

- McInnes CJ, Wood AR, Thomas K, Sainsbury AW, Gurnell J, Dein FJ, and Nettleton PF. Genomic characterization of a novel poxvirus contributing to the decline of the red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) in the UK. J Gen Virol 2006;87:2115-2125.

- Murphy FA, Calisher CH, Tesh RB, Walker DH. In memoriam: Robert Ellis Shope: 1929–2004. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(4):762–765.

- O’Conner DJ, Diters RW, and Nielsen SW. Poxvirus and multiple tumors in an eastern gray squirrel. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1980;177: 792-795.

- Shope RE, Hurst EW. Infectious papillomatosis of rabbits: with a not on the histopathology. Exp. Med. 1933;58(5):607–624.

- Terrell SP, Forrester DJ, Mederer H, and Regan TW. An epizootic of fibromatosis in gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) in Florida. J Wildl Dis 2002;38:305-312.

- Van Epps HL. Influenza: Exposing the true killer. J Exp Med. 2006;203(4):803.

- Zachary JF and McGavin MD. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012: 230-231, 326, 1020-1024.

- Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DP. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, 4th

Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell; 2016:263-264.