Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 8

October 24, 2018

CASE IV: 13-46415 (JPC 4048668-00).

Signalment: Adult, male, eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus)

History: Free-ranging eastern massasauga rattlesnake from Michigan.

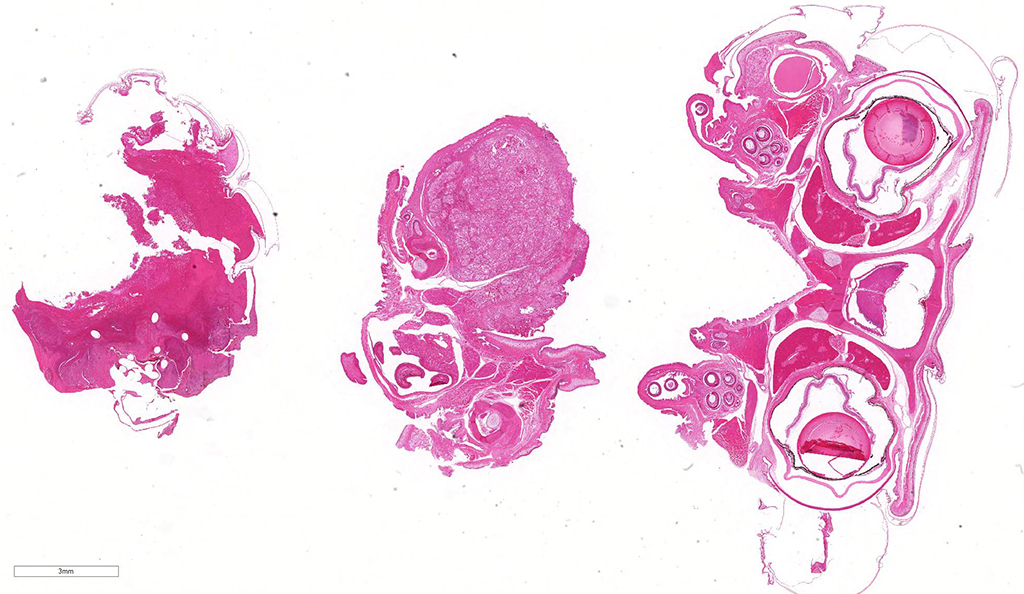

Gross Pathology: The mandible is markedly enlarged and distorted by firm swelling of the subcutis, up to 0.9 cm in thickness. Along the rostral aspect of mandible, a 1.5 cm x 0.4 cm region of the oral mucosa is red-brown and ulcerated. The spectacles are bilaterally light blue and opaque. Adhered along the entire length of the body, there are focally extensive regions of dull, retained scales (dysecdysis).

Laboratory results: Real time PCR positive for Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola

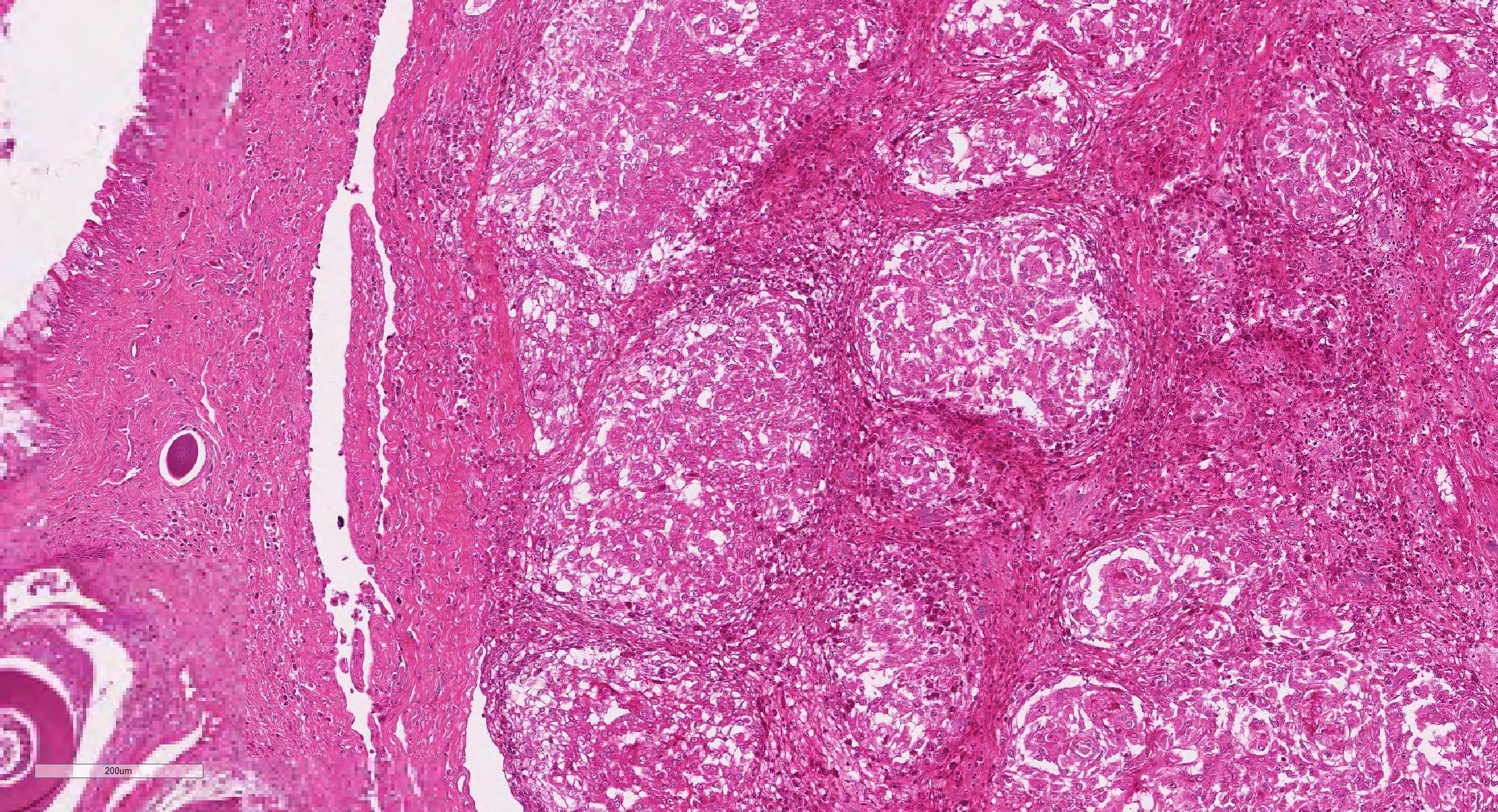

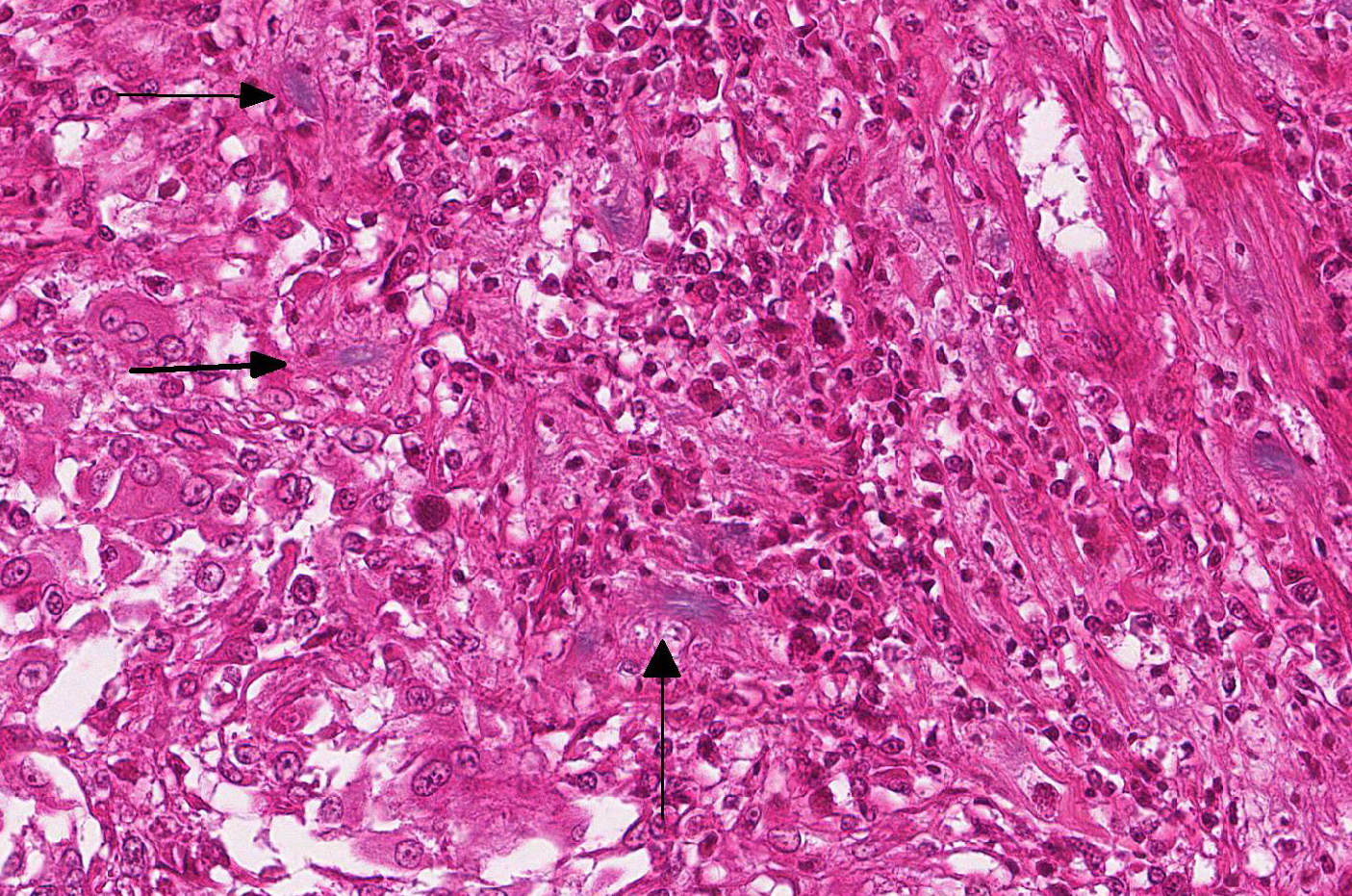

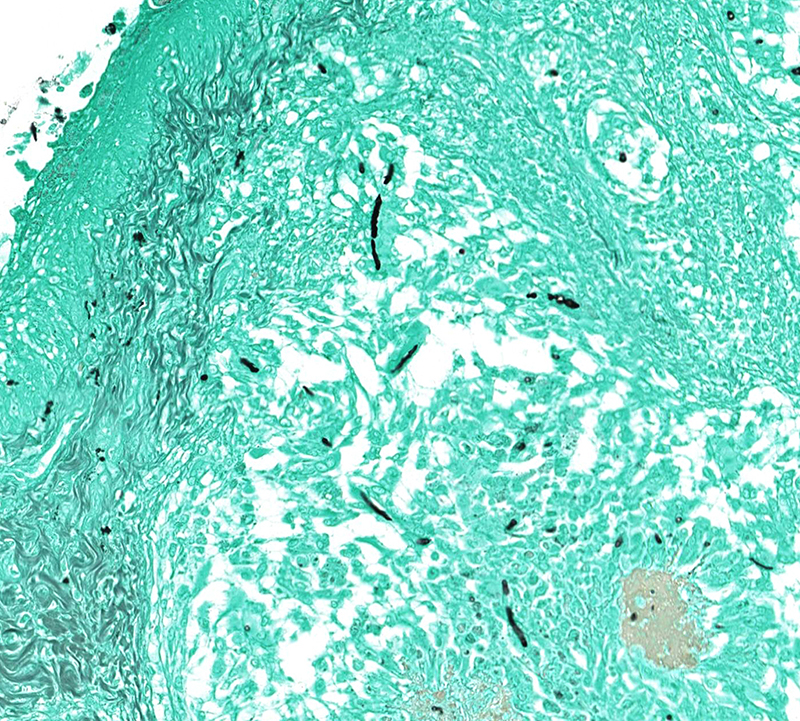

Microscopic Description: Effacing and expanding the dermis and subcutis of the right caudoventral mandible, compressing the adjacent skeletal muscle and dorsally elevating the overlying mucosa of the oral cavity are multiple coalescing granulomas centered on eosinophilic necrotic debris and small numbers of fungal hyphae. The hyphae are 3-5 um in diameter, parallel walled, septate, and occasionally branching. Areas of necrosis are surrounded by numerous epithelioid macrophages and few multinucleated giant cells containing up to 6 nuclei. The granulomas are further circumscribed by plump fibroblasts and dense bands of fibrous connective tissue that are infiltrated by many heterophils, fewer lymphocytes and plasma cells. There is also a free crust composed of numerous degenerate and viable heterophils, necrotic cellular debris, myriad small coccobacilli and a few fungal hyphae. The fungal hyphae stain black with Grocott’s Methenamine Silver (GMS).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: Head, mandible: Dermatitis and cellulitis, heterophilic and granulomatous, focally extensive, severe with fungi

Contributor’s Comment: Over the last decade, Snake Fungal disease (SFD) has become an emerging skin disease in certain populations of wild snakes in the Eastern and Midwestern United States. The keratinophilic fungus Ophidiomyces (formerly Chrysosporium) ophiodiicola has been consistently associated with SFD. Unlike other fungal members of the family Onygenaceae (order Onygenales), O. ophiodiicola has been recovered only from snakes. Published reports of fungal isolates confirmed via DNA sequencing or PCR assays have been reported in at least 12 different snake species.2,12

While clinical signs and disease severity may vary by species, fungal infection often leads to a fatal outcome, especially in eastern massasauga rattlesnakes.2 The most common clinical signs of O. ophidiicola are severe facial swelling and disfiguration. Other cutaneous lesions include scabs or crusty scales, subcutaneous nodules, skin ulcers, dysecdysis, and hyperkeratosis.2,11-13 Occasionally, fungal invasion may further progress to disseminated or systemic mycosis. Histologic lesions typically consist of cutaneous ulcers with thick adherent serocellular crusts and multiple granulomas within deeper tissues that are centered on variable numbers of fungal hyphae.2,11 Although not seen histologically in this snake, notable morphological characteristics for O. ophiodiicola may include formation of short, undulate, sparsely septate lateral branches and chains of cylindrical arthroconidia usually along the epidermal surface.8

The origin, transmission, and predisposing factors of infection with O. ophidiicola remain poorly understood. Occurrence of infection across different locations over a span of years suggests fungal presence within the environment. Histopathologic evidence of primary skin involvement is also consistent with environmental acquisition of infection.2 Recent culture and molecular based surveys of healthy captive and wild snakes have shown that the fungus is not a common constituent of the normal snake skin microflora.1,3

Aside from presence of the fungal elements in disease-associated lesions, specific pathological criteria for O. ophiodiicola associated SFD have not yet been established. Differentials for dermatomycosis of snakes should include other members of the genera Nannizziopsis, Paranannizziopsis, which have been well-detailed by Sigler et al.12 Proper diagnosis of O. ophiodiicola typically requires a combination of physical examination, histopathology, culture and/or molecular analysis such as PCR or DNA sequencing.11-13

Contributing Institution: University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine Department of Pathobiology and Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. http://vetmed.illinois.edu/path/

JPC Diagnosis: Mandible: Osteomyelitis, rhabdomyositis, cellulitis, and stomatitis, granulomatous, focally extensive, severe, with myofiber atrophy, ulcerative stomatitis, and fungal hyphae.

JPC Comment: Within the last generation, cutaneous and systemic fungal infections have resulted in dramatic declines of varies animal species on a global scale – Batrachochytridium dendrobatidis in amphibians (and a related species, B salamandrivorans in European salamanders), Pseudogymnoascus destructans in bats, and now, related species of Chrysosporium (Nannizziopsis) in various species of reptiles.3,12

Three lineages of closely related genera cause dermal or systemic infections in reptiles: the genus Nannizziopsis (N. vriesis, N. guarroi, and six additional species) infect various lizard species. Paranannizziopsis has four species which affect snakes and tuataras, and the species Ophidomyces ophiodiicola affects snakes.10,13

While considered an emerging threat, opinions differ as to whether O. ophiodiicola is a recently introduced pathogen, or a pathogen which has emerged and spread as a result of recent environmental changes.4 The first report of O. ophiodiicola was considered to be associated with a captive black rat snake with facial granulomas11, however, the agent was identified retrospectively in samples of imported brown tree snake suffering from rapidly progressive systemic mycosis.6 then has been identified in over 30 snake species, 6 families, and outbreaks in wild snakes in almost every state in eastern half of the United States.4 A number of cases of dermatomycosis in various species of snakes were subsequently re-evaluated and O. ophiodiicola was determined to be the culprit. While this rapid emergence of the disease suggests a newly introduced pathogen, subsequent cases may be identified 500-1000 miles distant from the closest report, activity not consistent with the “new pathogen” theory. Moreover, investigation of historical outbreaks of skin disease in wild snakes, couple with new molecular techniques has identified O. ophiodiicola in previous cases. One recent study documented a 74% incidence of O. ophidocola in cases of “hibernation sores” – a condition well known to herpetologists for decades.4

On a comparative note, invasive, occasionally fatal infections caused by Nannizziopsis sp. have been rarely identified in humans, often in immunosuppressed patients. N. obscura, N. infrequens (both good names for rare pathogens) have been indentified in patients sharing risk factors of HIV infection and/or recent travel to Africa. Abscesses in the brain, bone, viscera or soft tissues predominate; treatment with antifungals were successful in several cases. There is currently no evidence of zoonotic infections associated with Nannizziopsis sp.5

Reptiles have a diverse array of normal mycobiota of the skin. As such, PCR or culture should never be performed to diagnose fungal disease without paired histologic samples. Many fungi colonize the shed of snakes, and ecdysis may be a mechanism for snakes to prevent pathogenic fungal infections. Fungi that are primary pathogens in snakes are uncommon.7 Invasiveness, granulomatous dermatitis, and arthroconidia may increase the index of suspicion for SFD (and warrant culture) and help the pathologist to diagnose this condition over other, common, secondary fungal infections. Molecular testing is now not only considered the diagnostic test of choice, but has also resulted in the correct assignment of these morphologically similar fungi to appropriate genera (most importantly, Ophidiomyces ophidiicola.).10-13 Secondary, opportunistic, fungal infections are very common in snakes, and are frequently caused by hyalohyphomycotic fungi; this underscores the importance of evaluating fungal morphology and using ancillary diagnostics to screen for primary fungal diseases, such as SFD.7

The moderator discussed the diverse mycobiota of the skin of snakes, which is often composed of a number of secondary pathogens; however, subcutaneous infection and granuloma formation is very characteristic of this particular pathogen. Acid-fast staining to rule out mycobacteriosis is advisable in these cases from a practical aspect.

References:

- Allender MC, Dreslik MJ, Wylie DB, et al. Ongoing health assessment and prevalence of Chrysosporium in the eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus). Copeia.2013;1:97–102.

- Allender MC, Dreslik M, Wylie S, et al. Chrysosporium sp. infection in eastern massasauga rattlesnakes. Infect. Dis. 2011;17(12):2383-2384.

- Last LL, Fenton H, Gonyour-McGuire J, Moore M, Yabsley MJ. Snake fungal disease caused byu Ophiiomyces ophiodiicola in a free ranging mud snake. J Vet Diagn Invest 2016 28(6):709-713.

- Lorch JM, Knowles S, Lankton JS, Michell K, Edwards JL, Kapfer JM, Staffen RA, Wild ER, Schmidt KZ, Ballmann AE, Blodgett D, Farrell TM, Glorioso BM, Last LA, Price SJ, Schuler KL, Smith CE, Wellehan JFX, Bleher DS. Snake fungal disease: an emerging threat to wild snakes. Phil Trans R Soc B 2016; 371:20150547.

- Nourisseon C, Vidal-Roux, M, Cayot S, Jacomeet C, Bothorel C, Ledoux-Pilon A, Anthony-Moumoni F, Lesens O, Poirier P. Invasive infections caused by Nannizziopsis molds in immunocompromised patients. Emerg Inf Dis 24(3):549-552

- Nichols DK, Weyant RS, Lamirande EW, Sigler L, Mason RT: Fatal mycotic dermatitis in captive brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis). J Zoo Wildl Med 30(1): 111-118, 1999

- Ossiboff, R. In: Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Terio K, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. London, Academic Press, 2018.

- Paré JA, Rypien KL, Gibas CF. Cutaneous mycobiota of captive squamate reptiles with notes on the scarcity of Chrysosporium anamorph Nannizziopsis vriesii. Herpetol. Med. Surg. 2003;13(4): 10-15.

- Pare, JA, Sigler L. An overview of reptile fungal pathogens in the genera Nannizziopsis, Paranannizziopsis, and Ophidiomyces. J Herp Med Surg 2016: 26:1-2, 46-53

- Rajeev S, Sutton DA, Wickes BL, et al. Isolation and characterization of a new fungal species, Chrysosporium ophidiicola, from a mycotic granuloma of a black rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta). Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1264-1268.

- Sigler L, Hambleton S, Paré JA. Molecular characterization of reptile pathogens currently known as members of the Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii (CANV) complex and relationship with some human-associated isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51(10):3338-3357.

- Sleeman J. Snake fungal disease in the United States. National Wildlife Health Center Wildlife Health Bulletin 2013-02. http://www.nwhc.usgs.gov/disease_information/other_diseases/snake_fungal_disease.jsp. Updated May 21, 2013.