CASE IV:

Signalment: Adult, female, Antigone canadensis, greater sandhill crane

History: Two lesser snow geese and two greater sandhill cranes were submitted for postmortem examination to investigate the death of at least 30 birds that included a variety of duck species, lesser snow geese and greater sandhill cranes at a waterfowl management area.

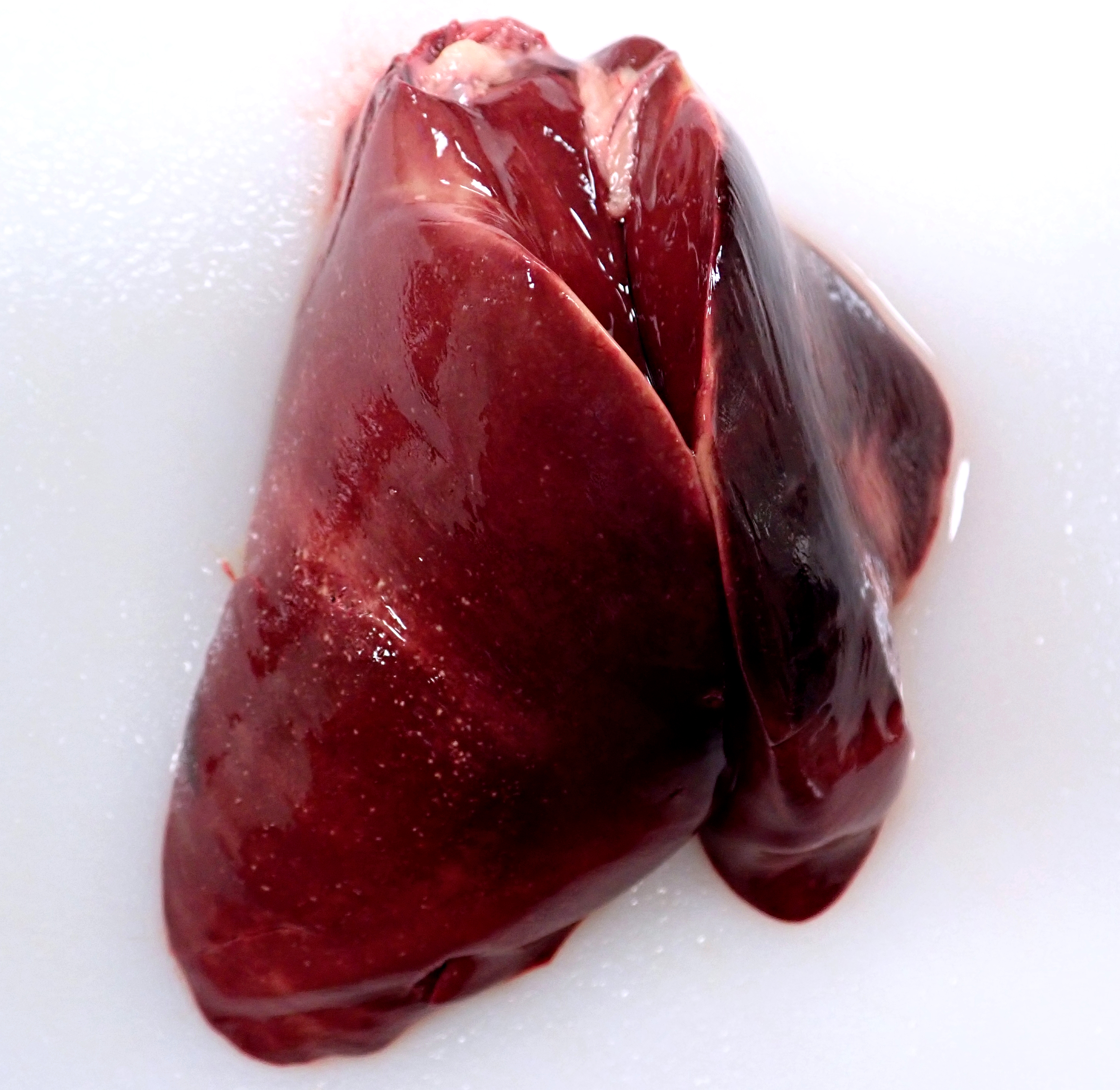

Gross Pathology: The crane was in good body condition and with minimal postmortem decomposition. The liver was enlarged, congested, and contained numerous random pinpoint tan foci. The spleen was enlarged and contained numerous coalescing pinpoint tan foci.

Laboratory Results

Pasteurella multocida was isolated from the liver and spleen.

PCR testing was negative for avian influenza virus and avian paramyxovirus.

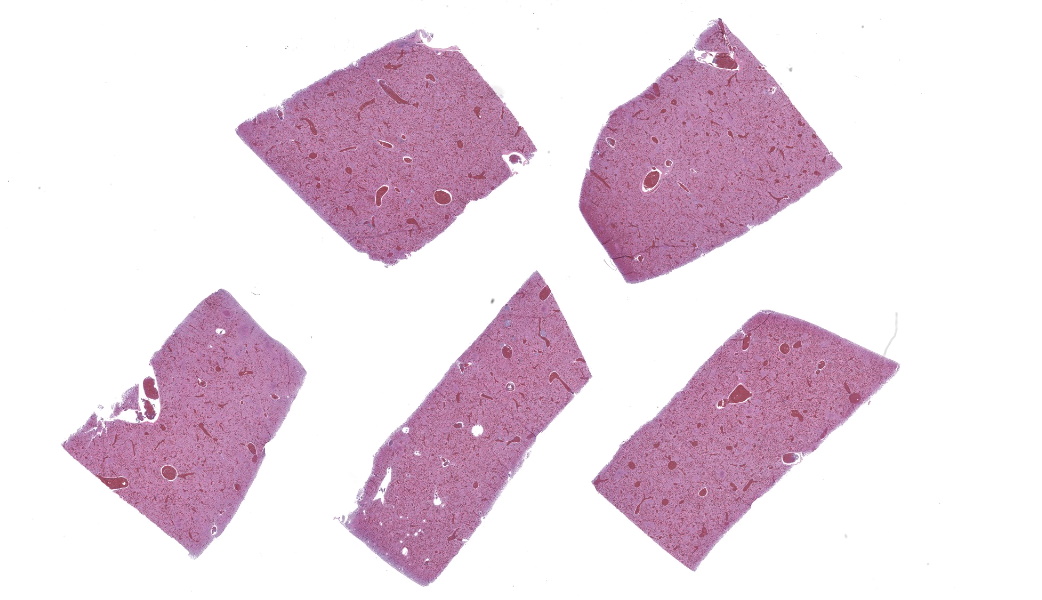

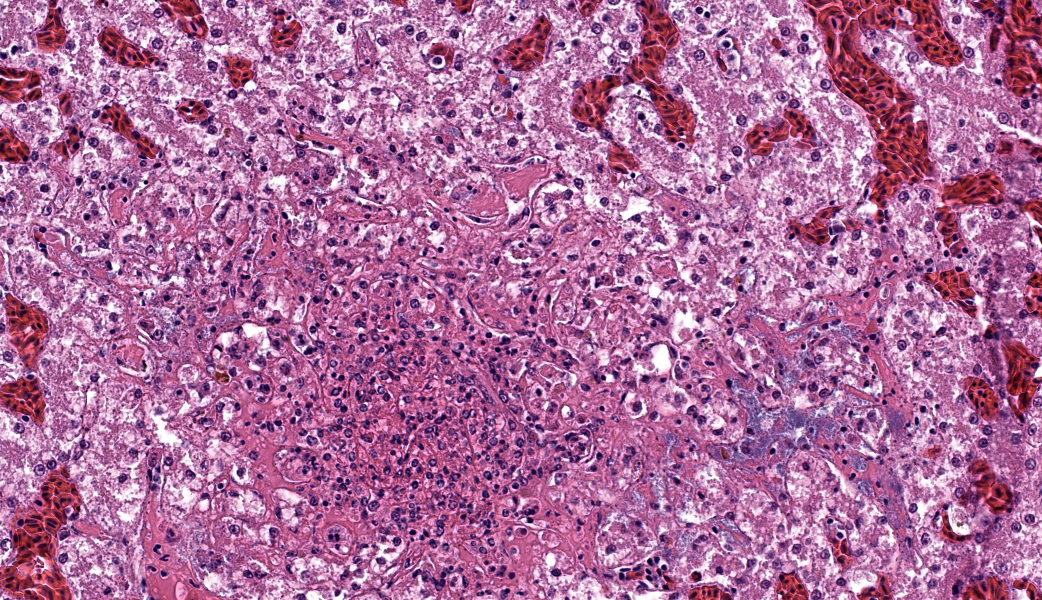

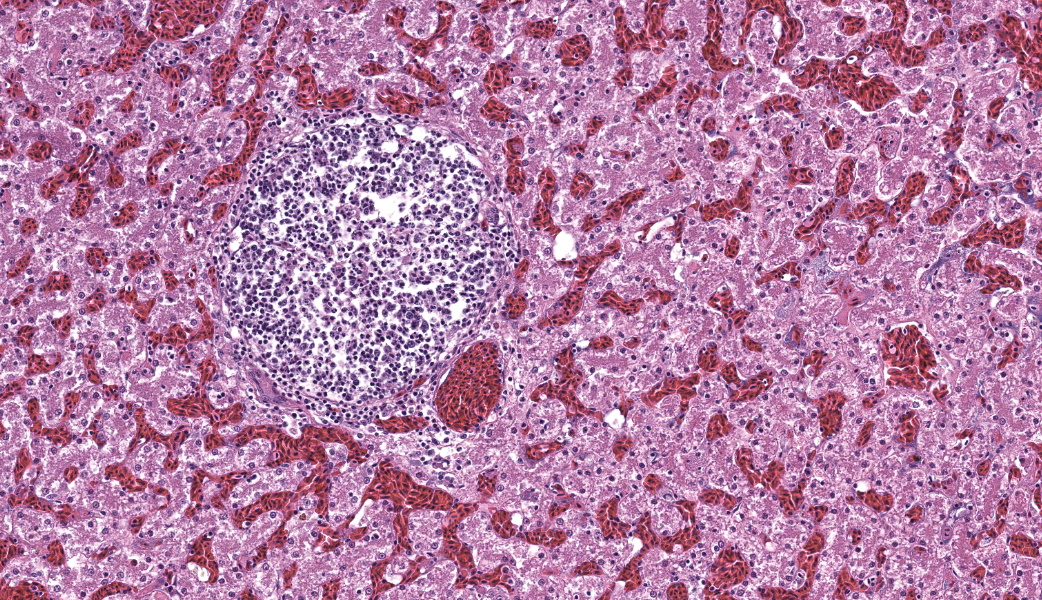

Microscopic Description: The liver has multiple random foci of necrosis that are filled with necrotic debris, fibrin, variable numbers of intact and degenerate heterophils and macrophages, and variable numbers of Gram-negative coccobacilli. There are multiple sinusoids that contain coccobacilli with small numbers of sinusoids that contain fibrin thrombi. The hepatocytes adjacent to the sinusoids with fibrin thrombi are often necrotic. There are small numbers of perivascular aggregates of lymphocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver – Hepatitis, necrotizing, heterophilic and histiocytic, random, multifocal with intralesional and intravascular Gram-negative coccobacilli and sinusoidal fibrin thrombi; etiology Pasteurella multocida.

Contributor’s Comment: Fowl cholera is a disease of birds caused by the Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium Pasteurella multocida.3,4,6,7,8 The bacterium is known to infect numerous species of birds including but not limited to domestic poultry, wild waterfowl, birds of prey, and birds in zoological collections. Fowl cholera typically occurs as an acute fatal respiratory and septicemic disease with death occurring within 24-48 hours. Chronic and even benign infections with P. multocida can occur. Of the domestic poultry, turkeys are more susceptible to infection with P. multocida than chickens.4,7 Adult chickens are most susceptible to infection with P. multocida that young chickens.4,7 Among wild birds, outbreaks of fowl cholera typically occur in North American waterfowl in wetlands or nesting areas.3,6,8

P. multocida is likely transmitted to susceptible birds from the contaminated environment or bird-to-bird contact.3,6,8 Large numbers of P. multocida are shed in nasal, oral and ocular secretions of live sick birds, and large numbers of P. multocida contaminate the environment from the carcasses of dead birds.3,4,6,7,8 Immediate removal of carcasses from the outbreak area is important for the management of avian cholera in wild birds as the bird carcasses will continually contaminant the environment with P. multocida if left to naturally decompose or be consumed by scavengers.3,6,8 How P. multocida is transmitted between outbreak areas is not known, but it is believed that some lesser snow geese and Ross’s geese can be carriers of P. multocida.3,8,9 In some wetlands, an increase in the population of lesser snow geese has been associated with an increase in the incidence and mortality numbers of avian cholera.2,3,8,9 The ability of P. multocida to persist in the environment has not been fully clarified.3,6,8 However, there are some studies that show P. multocida cannot be isolated from the wetland environment after 7 weeks of an outbreak.1,8 Thus, long term persistence of the bacterium in the environment is not likely the source of multiple outbreaks in the same area that occur years apart.

In acute fowl cholera, the most likely sign of disease first noticed is the death of large numbers of birds.4,6,7,8 Clinical signs are only evident for a short period prior to death and include anorexia, ruffled feathers, depression, oral and nasal discharge, increased respiratory rate, diarrhea, and cyanosis of nonfeathered skin. Birds that die of acute fowl cholera are in good body condition and often will still have food in the esophagus and crop. These birds may have congestion of their organs with hemorrhages on serosal surfaces and in the heart, lungs, fat, and other organs. Birds dying acutely with fowl cholera can have multifocal random tan foci in an enlarged liver. The spleen can be enlarged and have multifocal random tan foci. Microscopically, the liver, spleen and lung can have random foci of necrosis filled with heterophils and bacteria. Lesions in the lung are most common in turkeys. There are often bacteria within numerous blood vessels. Chronic P. multocida infections in birds are often localized infections in comparison to the fatal septicemia of acute fowl cholera.4,7

Localized infections of P. multocida most commonly occur in the respiratory tract. Any part of the respiratory tract can be involved including the lungs, sinuses, and pneumatic bones. A common chronic respiratory tract lesion in turkeys with P. multocida is pneumonia. Other chronic infections with P. multocida in birds include conjunctivitis, arthritis, pododermatitis, salpingitis, and otitis media. The microscopic lesions of chronic P. multocida infections in birds tend to be heterophilic inflammation mixed with macrophages and multinucleated giant cells.

Contributing Institution:

New Mexico Department of Agriculture Veterinary Diagnostic Services

https://nmdeptag.nmsu.edu/labs/veterinary-diagnostic-services.html

JPC Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, acute, random, marked, with fibrin thrombi and numerous colonies of coccobacilli.

JPC Comment: Fowl cholera was last seen in the WSC in Conference 22, Case 1 of the 2014-2015 WSC. Sandhill cranes are not usually a species that comes to mind in a classic diagnosis of fowl cholera. However, Pasteurella multocida happens to be one of the leading bacterial causes of death for sandhill cranes in the U.S. and is commonly isolated from wild bird populations. There is some evidence that migratory bird populations may contribute to outbreaks.3,7 The contributor’s comment in this case provides a thorough overview of P. multocida in common avian species and is worth the read. Much of the discussion held in this case revolved around topics in their write-up.

P. multocida is associated with a wide range of diseases in several species of animals. Some of the major diseases in domestic species include hemorrhagic septicemia in ungulates, atrophic rhinitis in swine, and fowl cholera in wild and domestic birds. P. multocida sports a handful of key virulence factors that include a capsule, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), iron-regulated proteins, and outer membrane proteins OmpA, OmpH, sialylation of outer membrane components, and the adhesion protein filamentous hemagglutinin B2 (FhaB2).5 The FhaB proteins are both surface-associated and secreted by the bacteria, the latter of which is necessary to establish infection in turkeys upon mucosal exposure.

It is thought that FhaB2 in P. multocida functions as an adherence molecule involved in colonization and invasion of respiratory mucosal surfaces in turkeys.5 Due to the key role FhaB2 plays in the pathogenesis of fowl cholera, there have been vaccine trials using recombinant FhaB2 peptides that demonstrated anti-FhaB2 antibodies effectively protected turkeys against challenge with both homologous and heterologous strains of P. multocida.5 This wide cross-protection is thought to be due to the high degree of conservation of P. multocida FhaB2 protein sequences.

References:

- Blanchong JA, Samuel MD, Goldberg DR, Shadduck DJ and Lehr MA. Persistence of Pasteurella multocida in wetlands following avian cholera outbreaks. J Wildl Dis. 2006;41(1):33-39.

- Blanchong JA, Samuel MD, Mack G. Multi-species patterns of avian cholera mortality in Nebraska’s rainwater basin. J Wildl Dis. 2006;41(1):81-91.

- Botzler RG. Epizootiology of avian cholera in wildfowl. J Wildl Dis. 1991;27(3):367-395.

- Christensen JP, Bojesen AM, Bisgaard M. Fowl cholera. In: Pattison M, McMullin PF, Bradbury JM, Alexander DJ, eds. Poultry Diseases. 6th ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

- Dassanayake RP, Briggs RE, Kaplan BS, Menghwar H, Kanipe C, Casas E, Tatum FM. Pasteurella multocida filamentous hemagglutinin B1 (fhaB1) gene is not involved with avian fowl cholera pathogenesis in turkey poults. BMC Vet Res. 2025;21(1):207.

- Friend M. Avian cholera. In: Friend M, Franson JC, Ciganovich EA, eds. Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases General Field Procedures and Diseases of Birds. United States Geological Survey; 1999.

- Glisson JR. Pasteurellosis and other respiratory bacterial infections. In: Saif YM, Fadly AM, Glisson JR, McDougald LR, Nolan LK, Swayne DE, eds. Diseases of Poultry. 12th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- Samuel MD, Botzler RG, Wobeser GA. Avian cholera. In: Thomas NJ, Hunter DB, Atkinson CT, eds. Infectious Diseases of Wild Birds. Blackwell; 2007.