Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 10

November 29th, 2017

CASE III: N-103/17 (JPC 4102670).

Signalment: 7-year-old, male, neutered, Doberman pinscher, Canis familiaris, canine.

History: This 7-year-old Doberman was presented with recurrent peritoneal and pleural effusions of 3 weeks duration. Echocardiography was performed without heart alterations. Blood biochemical examination revealed increased hepatic enzymes and decreased albumin parameters. A marked lack of coagulation factors was also detected without improvement after plasma transfusions. No more clinical information was supplied.

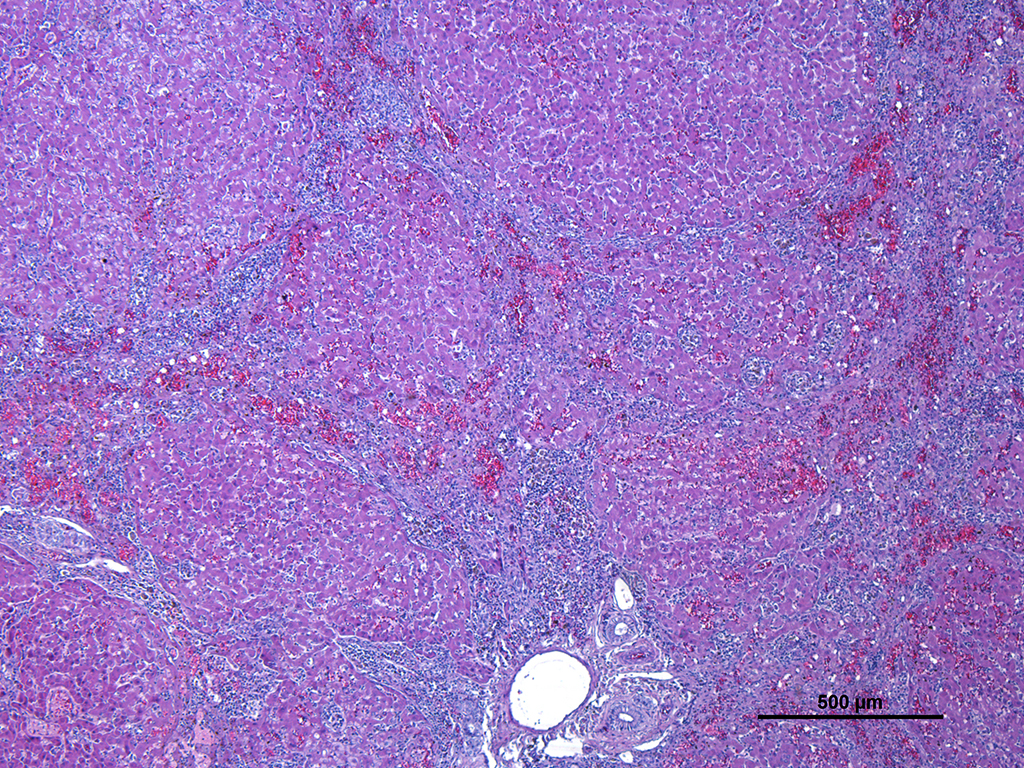

Gross Pathology: Mucous membranes were icteric and the abdomen was visibly distended. Approximately 9 litres of clear yellowish free fluid in the abdominal cavity were observed, and 3 litres of similar fluid was present in the thoracic cavity. The liver was diffusely yellow to tan, decreased in size and showed multiple multifocal to coalescing micro-nodulations.

Laboratory results:

None provided.

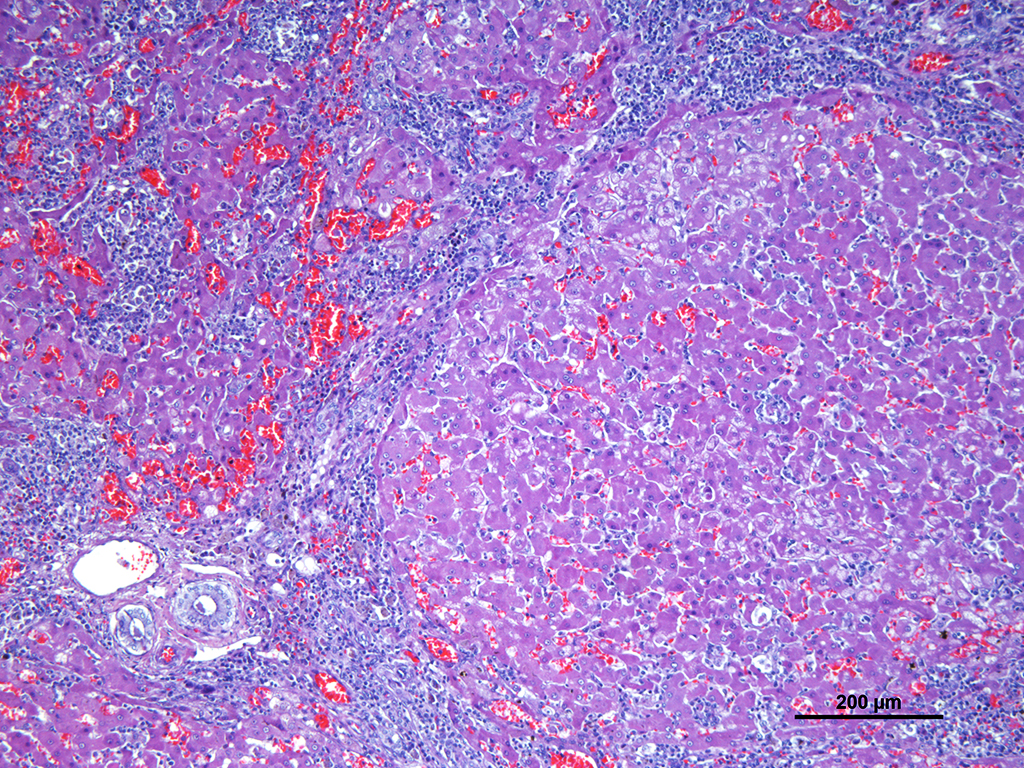

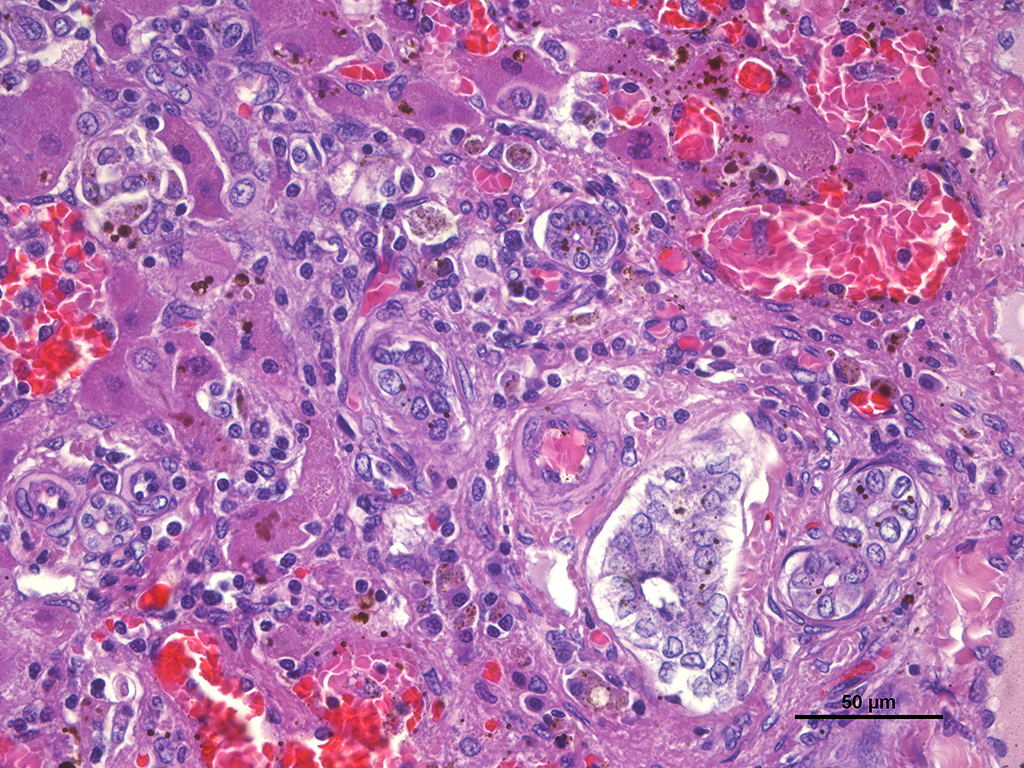

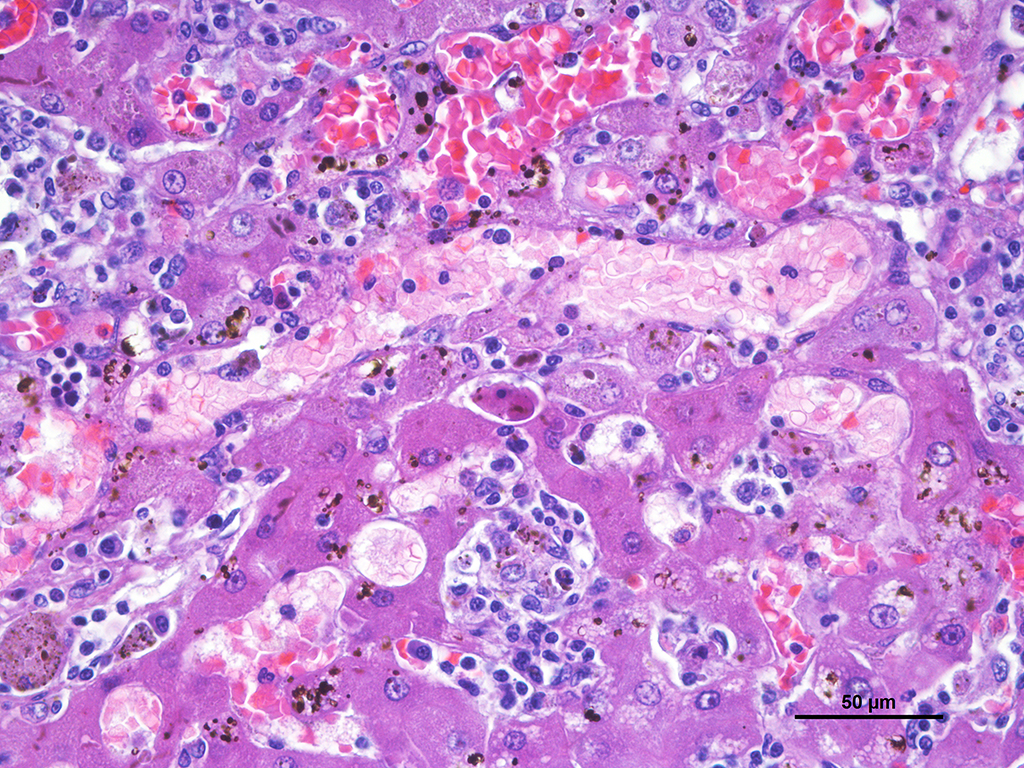

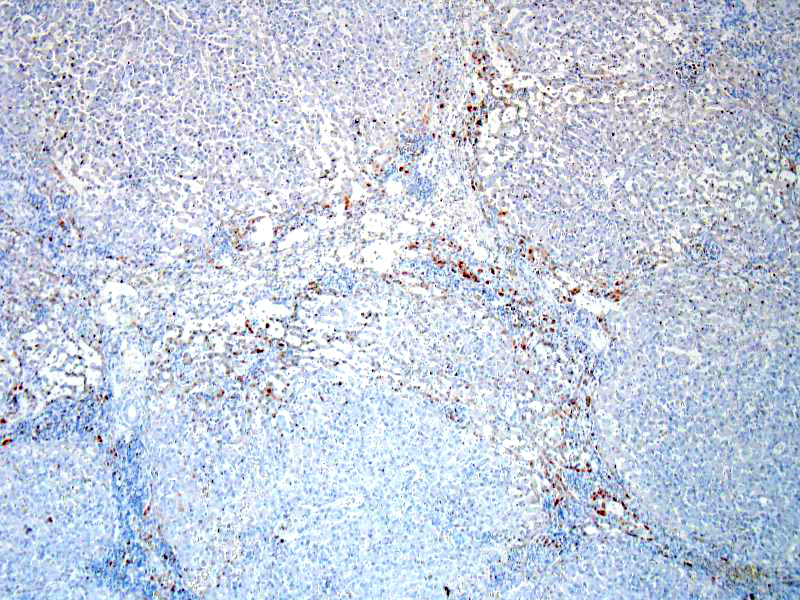

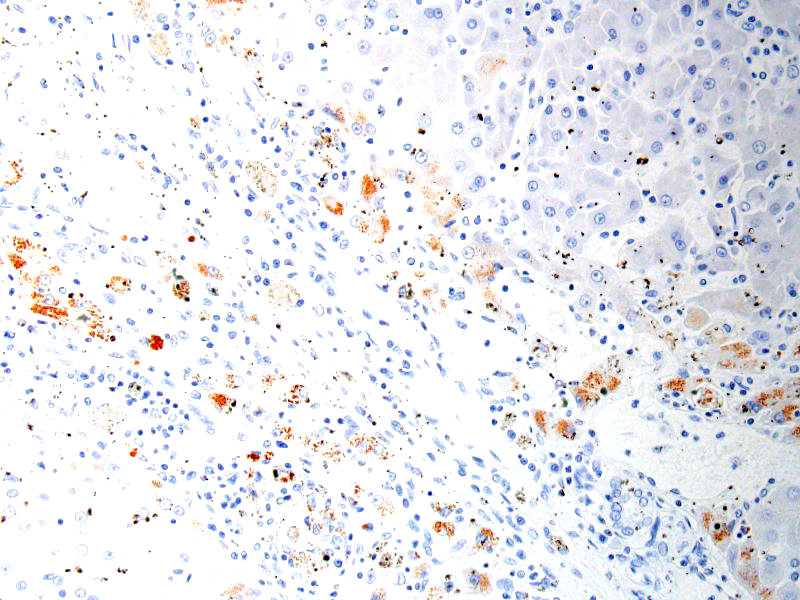

Microscopic Description: Liver: Diffusely affecting all the section there is a severe chronic degenerative process together with multifocal nodules of hepatic regeneration. There is a markedly reduction of the diameter of hepatic lobules because of loss of numerous hepatocytes. Marked portal-to-portal bridging is observed. Which is composed of moderate biliary hyperplasia and mild fibrosis along with severe inflammatory infiltrate mainly compose of macrophages (most of them arranged in aggregates) and abundant lymphoplasmacytic cells. Numerous biliary ducts contain moderate amount of amorphous yellowish material in the lumen and small bile casts are located in canaliculi (cholestasis). Biliary pigment is also located in the cytoplasm of Kupffer cells and hepatocytes. Multifocally sinusoids are distorted, dilated and markedly congested. Numerous hepatocytes appear enlarged with marked eosinophilic nucleolus. Degenerated changes of centrilobular hepatocytes can be seen: intracytoplasmic non-stained, well-defined micro vacuoles (lipid vacuoles) and cytoplasm rarefaction (hydropic degeneration). Also, scattered hepatocytes appear individualised, hypereosinophilic and karyorrhectic (apoptotic hepatocytes). There are multifocal areas of hepatic regeneration consistent of well-delimitated nodules of viable hepatocytes surrounded by fibrous tissue. Cells of the hepatic capsule appear plump and reactive.

SPECIAL STAINS: Rubeanic acid stain was performed and abundant green granular pigment observed in the cytoplasm of numerous hepatocytes in periportal areas.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Chronic, diffuse, severe hepatocellular degeneration and loss, with intrahepatocellular copper, severe bile stasis, nodular regeneration and moderate lipidosis (end-stage liver (cirrhosis)), Doberman, canine.

Contributor’s Comment: The alteration of clinical parameters observed in this case (hypoalbuminemia, hepatic enzymes increased and lack of coagulation factors) was secondary to chronic hepatic failure. Hypoalbuminemia lead to multiple effusions in body cavities and jaundice was secondary to a severe biliary stasis.

In this case, acid rubeanic tissue staining revealed numerous intracytoplasmic green granules in hepatocytes. Therefore, the primary cause of the chronic hepatic failure and the end-stage liver was the chronic copper accumulation and toxicity.

Hepatic injury in copper poisoning of domestic animals frequently is the result of progressive accumulation of copper within the liver. Hepatic copper toxicosis can result from a primary metabolic defect in hepatic copper metabolism, altered hepatic biliary excretion of copper, or from excess dietary intake of the element.2

Hepatic copper accumulation in association with chronic hepatitis has been documented in Doberman, but apart from the recognized genetic mutation in the COMMD1 gene in Bedlington Terriers, leading to a primary copper storage disease with impaired copper excretion, the pathogenesis of the Doberman copper accumulation remains unclear.2,4

Copper is an essential trace element of all cells, but even a modest excess of copper can be life-threatening because copper must be properly sequestered to prevent toxicosis. Normally, serum copper is bound to ceruloplasmin and the majority of hepatic copper is bound to metallothionein and stored in lysosomes. Excess copper can lead to the production of reactive oxygen species that initiate destructive lipid peroxidation reactions that affect the mitochondria and other cellular membranes.1

In cases of chronic hepatitis caused by copper accumulation, the liver is usually small, often with an accentuated lobular pattern; severely affected livers are characterized by architectural distortion, which ranges from a coarsely nodular texture to an end-stage liver. Chronic hepatitis, depending on the duration of inflammation and injury, is characterized by portal and periportal mononuclear cell inflammation and fibrosis of portal areas that may extend into adjacent periportal areas of the lobule, leading to the prominent lobular pattern. Small aggregates of pigmented macrophages, containing copper and lipofuscin, surrounded by mononuclear inflammatory cells are a reliable feature of copper excess. With progression, hyperplastic nodules and bridging fibrosis develop.3

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Fibrosis, bridging and portal, diffuse, severe with macronodular hepatocellular regeneration, piecemeal necrosis, cholestasis, siderosis, and sinusoidal capillarization, Doberman pinscher (Canis familiaris), canine.

Conference Comment: Doberman Pinchers are one of a number of dog breeds (Bedlington Terrier, West Highland White Terrier, Labrador Retriever, American and English Cocker Spaniel, Skye Terrier, Standard Poodle, Dalmatian, and English Springer Spaniel) that are predisposed to chronic hepatitis. In some of the aforementioned breeds genetic mutations have been identified (Bedlington Terriers with mutations in the COMMD1 gene are described above) but the majority of them are idiopathic. There is an association between excess copper accumulation and chronic liver disease but the exact mechanism has not been worked out yet.2 Sheep are especially sensitive to excess copper because they don’t efficiently regulate copper storage. Although copper is a necessary element for cellular metabolism, it is far from innocuous, and must be sequestered to prevent toxicosis. In serum, it is bound to ceruloplasmin, and in the liver, it is bound to metallothionein and stored in lysosomes. Even small amounts of unbound, excess copper, results in the production of reactive oxygen species that lead to lipid peroxidation causing mitochondrial and cell membrane damage. Copper toxicosis can occur by the following mechanisms: (1) dietary excess (especially in sheep); (2) inadequate molybdenum in feed which normally antagonizes copper; (3) ingestion of pyrrolizidine alkaloids (Heliotropium, Crotalaria, Senecio species) which prevent hepatocyte mitosis which increases copper load on surviving hepatocytes; (4) disorders in copper metabolism (mentioned above).1

This case engendered spirited discussion concerning the location of the copper and its causality of the chronic changes in this animal. In this individual, the copper is located exclusively in periportal regions, as is seen in many cases of chronic hepatitis. The majority of the parenchyma that is replaced by nodules of regenerating hepatocytes has not accumulated copper; relegating the demonstration of copper to the small amount of “original” liver present in the slide. Whether regenerative nodules do not accumulate copper as a result of an adaptive response or simply as a result of their relatively recent maturation, has not been conclusively determined.2 However, at this point in lesion development, the attendees believe that it is difficult, if not impossible to determine the link between the copper accumulation in hepatocytes and its causality, if any, to the ongoing cirrhotic process.

Another very interesting change in this liver is the dilation of periportal sinusoids, which resembles “sinusoidal capillarization”, a change described in chronic hepatitis in humans.

In the normal animal, liver sinusoidal endothelium varies markedly from capillary endothelium in other organs, as it exhibits fenestration, lacks a basement membrane, and does not express factor VIII-related antigen , platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecules (PECAM-1), CD-34, or E-selectin. In addition, affected sinusoids exhibit decreased compliance with sinusoidal blood flow (likely resulting in the dilation noted in this slide in periportal sinusoids) and possibly contributing to portal hypertension.4

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Pathology Department,

Veterinary Faculty,

Autonomous University of Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain.

References:

- Brown DL, Van Wettere AJ, Cullen JM. Hepatobiliary system and exocrine pancreas. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017: 440.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2016: 302-303, 342.

- Mandigers PJ, Van den Ingh TS, Spee B, Penning LC, Bode P, Rothuizen J. Chronic hepatitis in doberman pinschers: a review. Vet Q. 2004;26(3):98-106.

- Xu B, Broome U, Uzumel S, Ge, X, Kumaga-Baaesch M, Huttenby K, Christenson B, Ericzon B, Holgersson J, Sumitran-Holgersson S. Capillarization of hepatic sinusoid by liver endothelial cell-reactive autoantibodies in patients with cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis. Am J Pathol 2003 163(4) 1275-1289.