Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 12

11 December 2019

CASE III: WSC Case 2 HE (JPC 4118136).

Signalment2-year-old, intact male, Harlan Sprague-Dawley rat (Rattus norvegicus)

History: This rat was a terminal sacrifice (Test Day 730) animal from the control (untreated) group of a chronic, 2-year carcinogenicity study. No clinical signs or gross lesions were noted.

Gross Pathology: N/A

Laboratory results: N/A

Microscopic Description:

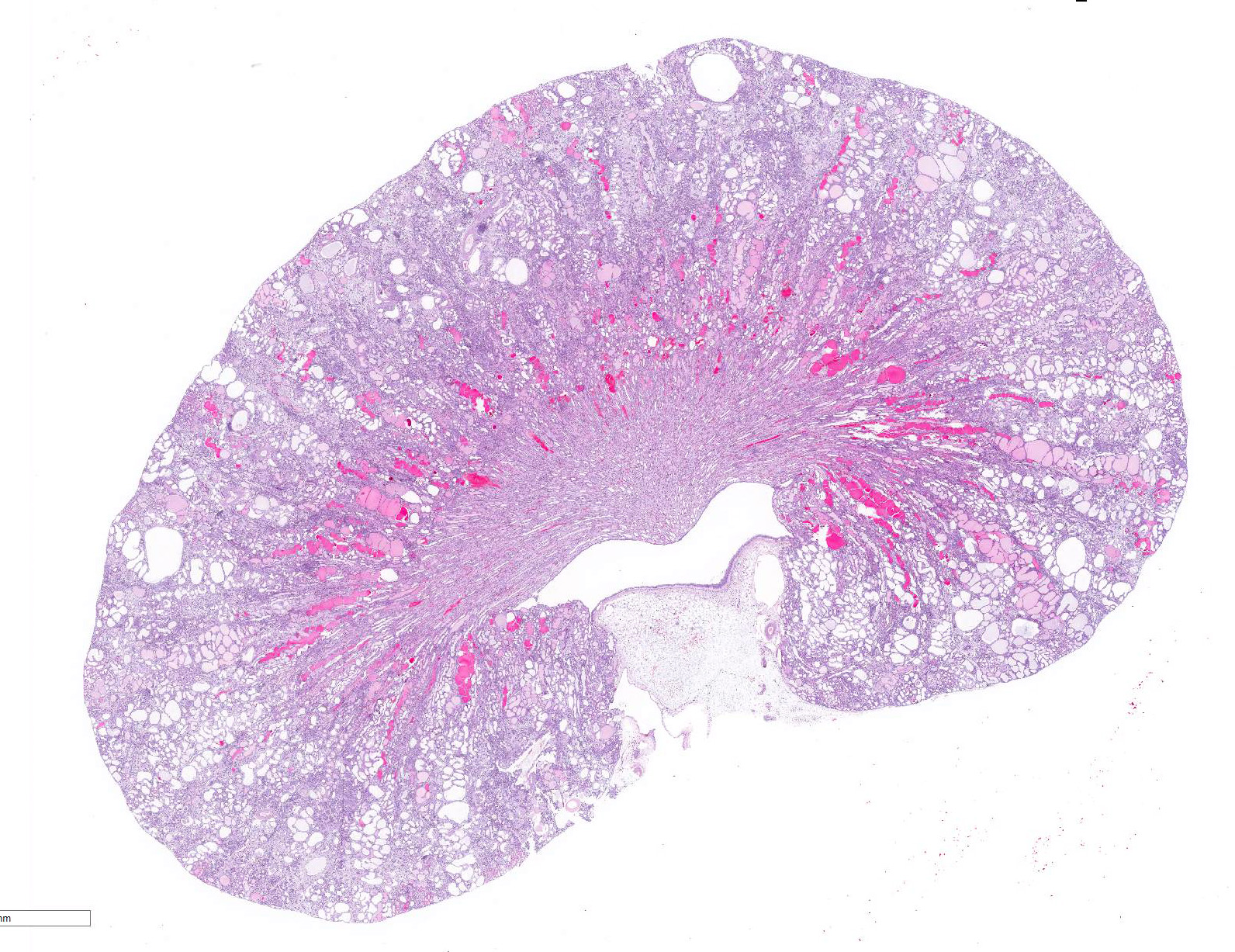

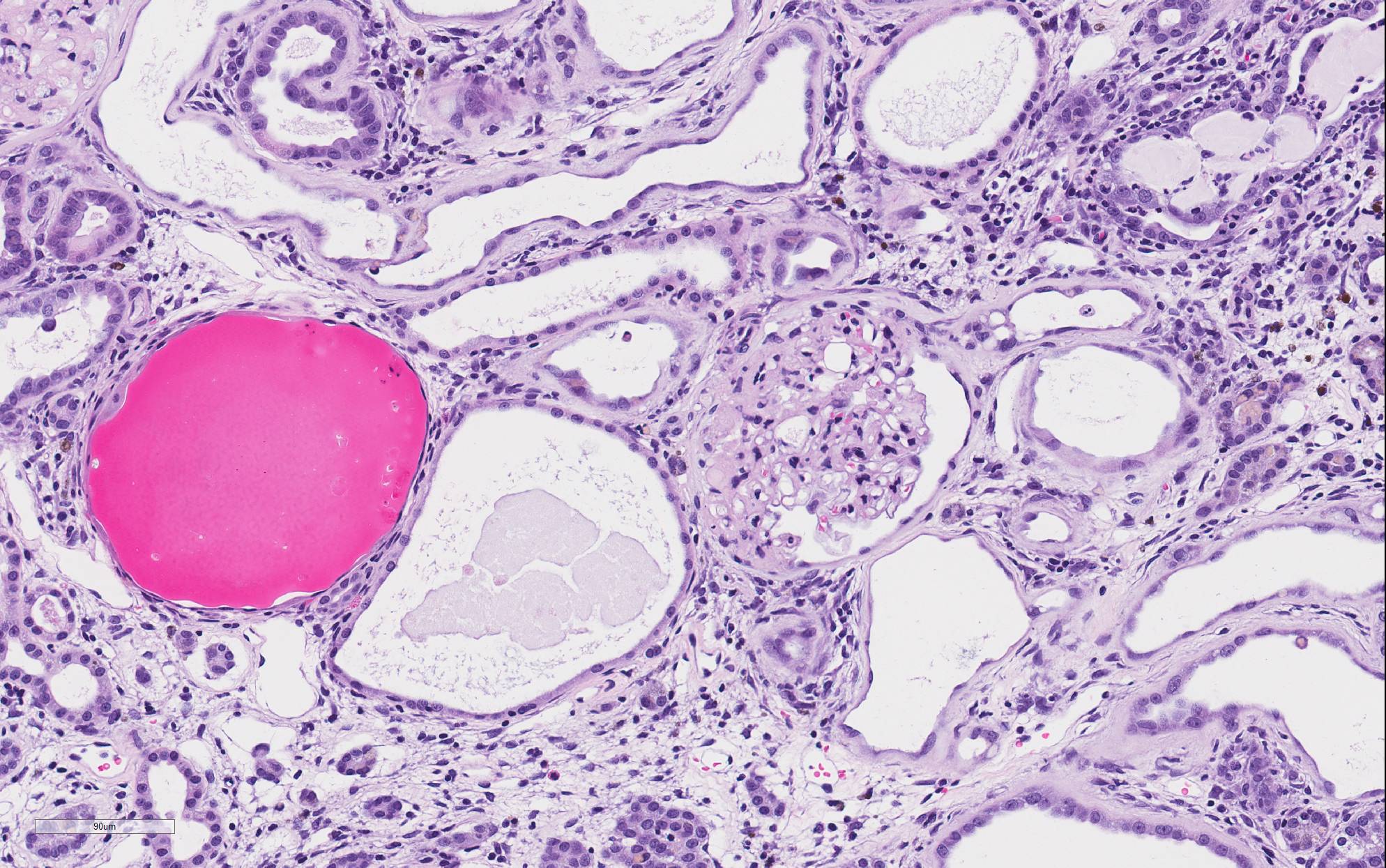

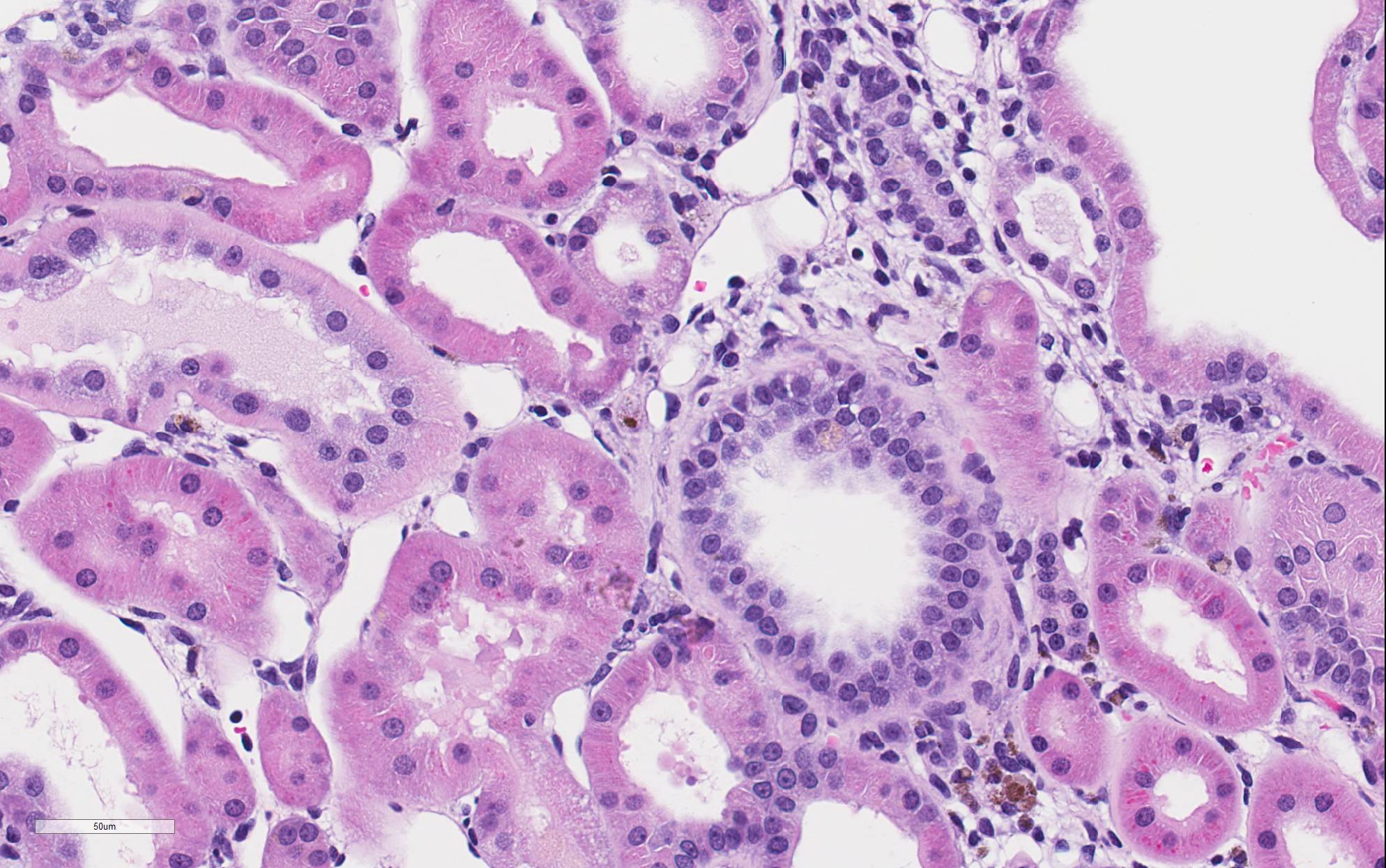

There is marked, irregular undulation along the capsular cortical surface. Diffusely throughout the cortex, there is moderate loss of renal tubules with replacement and wide separation of remaining tubules by abundant interstitial fibrous connective tissue, edema, and mixed inflammatory cells, including predominantly small lymphocytes and plasma cells. Low numbers of brown, granular pigment-laden (hemosiderin-laden) macrophages are also scattered throughout the cortical interstitium. Multifocal small interstitial hemorrhages are also present. The majority of remaining renal tubules are moderately to marked dilated and vary from empty to often filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous fluid or protein (hyaline) casts. Occasionally, a few scattered tubules have sloughed, necrotic epithelial cells and/or small intraluminal clusters of degenerative neutrophils admixed with necrotic cellular and nuclear debris and rare erythrocytes. Renal tubular epithelial changes range from cytoplasmic swelling and vacuolization (degeneration) to attenuation and atrophy. The tubular basement membrane is often thickened and hyalinized. Frequent scattered regenerative tubules are also present. Regenerative tubules are lined by one or multiple layers of crowded, plump epithelium characterized by slight cytoplasmic basophilia and large, vesicular nuclei with a single prominent nucleolus and increased mitoses. Rarely, a small papillary projection of jumbled renal tubular epithelium projects into the lumen. The majority of glomeruli are enlarged with glomerular tufts segmentally to globally expanded by increased mesangial fibrous connective tissue, Bowman"s capsule thickened and hyalinized, and periglomerular fibrosis (glomerulosclerosis). The parietal epithelium lining Bowman"s capsule is often hypertrophied and glomerular tufts are multifocally adhered to Bowman"s capsule (synechiae). The urinary space is often moderately dilated. A few shrunken, obsolescent glomeruli are also seen.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Kidney: Tubular degeneration, atrophy, necrosis, and regeneration, diffuse, severe with thickened basement membranes, tubular ectasia and hyaline casts, chronic interstitial nephritis and fibrosis, and glomerulosclerosis, segmental to global (chronic progressive nephropathy).

Contributor Comment: Chronic progressive nephropathy (CPN) is very common in all conventional strains of laboratory rat, with the highest incidence and severity in the Fischer 344 and Sprague-Dawley strains.2-4 The disease also occurs at a higher incidence and with progressively greater severity in male rats than in female rats.2-4,6 CPN is also a very common spontaneous renal disease of aging laboratory mice.3-4,6 A similar disease has been described in the gerbil, common marmoset, and naked mole rat. 5,6,8 In guinea pigs, segmented nephrosclerosis shares some features with CPN.5

CPN is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in laboratory rats.3,4 Although commonly thought of as an aging disease, many rats start developing the earliest lesions of CPN as juveniles (2-3 months old).3 The disease progresses throughout the life of the animal, eventually leading to end-stage renal disease in the rat.2-4 Renal failure from CPN can sometimes account for up to 50% or more of unscheduled male rat deaths in chronic carcinogenicity bioassays.3

The cause of CPN is unknown2-4, although Manskikh recently proposed a hypothesis for an expanding somatic mutant clone of precursor cells of tubular epithelium as the inciting cause.6 A number of dietary and hormonal factors are known to influence the incidence and severity of disease. The primary diet-related factors of importance are total caloric intake as well as source and amount of protein in the diet. Restricting caloric intake and reducing protein in the diet can reduce the incidence and severity of CPN. With regard to hormonal factors, the sex predisposition of the disease is linked to the presence of androgens, rather than an absence of estrogen.2-4

Classically, the glomerulus has been thought to be the primary target, with hyperfiltration being the underlying basis for the pathogenesis.3-5 This theory has been perpetuated due to the influence of high protein diets on disease progression and the associated clinical pathology finding of albuminuria in affected animals. However, this proposed glomerular hyperfiltration pathogenesis has not been proven; in fact, in aging rats, there is no evidence for a causal relationship between glomerular capillary blood pressure and the structural damage to glomeruli, arguing against this theory of a primary hemodynamic mechanism.4 Additionally, the earliest lesion of CPN that is detectable by light microscopy is actually a renal tubular lesion â a focal simple tubular hyperplasia of the P1 segment of a proximal tubule. This focal tubular lesion progresses to a small focus of affected tubules within a nephron and eventually to involve adjacent nephrons. Tubular basement membrane thickening is often a very prominent feature. Glomerular lesions generally develop later in the course of the disease.2-4 However, it cannot be ruled-out that a functional alteration in the glomerulus which cannot be detected microscopically may occur prior to this tubular lesion. During later and more severe stages of the disease, CPN is predominantly characterized by both degenerative and regenerative tubular changes, including numerous protein casts, as well as prominent segmental to global glomerulosclerosis.1-3 In severe grade cases, vesicular alteration of the renal papilla can be seen.7 Deposition of interstitial extracellular matrix (fibronectin, thrombospondin, collagens I and III) and infiltration by mononuclear inflammatory cells is often seen as well but these components are generally mild and not prominent features of the disease.1-3 Notably, vascular lesions are not a part of the disease.3,4

With regard to experimental studies and chronic carcinogenicity bioassays, some chemicals can induce exacerbation of CPN and, given the proliferative nature of the disease, advanced CPN is itself a risk factor for a marginal increase in the incidence of renal tubule tumors.2-4 In humans, the most common renal diseases are diabetic nephropathy and hypertensive nephropathy. The biology and lesions of rat CPN do not mirror those of either of these nephropathies nor of any of the additional known, less common nephropathies of humans; there is no known counterpart of rat CPN in humans.3 As such, there is debate over the conclusions that can be drawn from chronic carcinogenicity bioassays using rats regarding small increases in the incidence of renal tubule tumors and the relevance to human health. When designing experiments and interpreting the data from studies using the laboratory rat, relevance for species extrapolation to humans needs to be considered, particularly with regard to determining nephrotoxic effects and risk for renal tumor development.

Contributing Institution:

National Toxicology Program

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

111 TW Alexander Drive, PO Box 12233

Research Triangle Park, NC 27709

https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/atniehs/labs/lep/ntp-path/index.cfm

JPC Diagnosis: Kidney: Nephritis, interstitial, chronic, diffuse, severe, with membranous glomerulonephritis, synechiae, tubular loss, degeneration, necrosis, and regeneration, and marked interstitial fibrosis.

JPC

Comment: The

contributor has provided an excellent review of chronic progressive nephropathy

of rats (CPN), a very common age-related finding in laboratory rodents, which

may have an important and deleterious effect on analysis in chronic studies.

From a strain perspective, Sprague-Dawley and Fischer 344 appear to be the most

affected by this condition, followed by Wistar, Long-Evans, and Brown Norway

strains, with Buffalo and Osborne-Mendel the most resistant.1 The changes

are grossly apparent only in the later stages of disease, presenting as kidneys

which are decreased in size with an irregular contour, and a golden, rather

than brick-red coloration.

Microscopically, lesions may be seen as early as 2-3 months of age in male rats

of predisposed strains as individual regenerative tubules within the cortex

with basophilic cytoplasm, epithelial crowding, and an irregularly thickened

basement membrane. Affected tubules will accumulate hyaline material in their

lumen over time, predominantly in inner stripe of the outer medulla (descending

loop of Henle). Over time, individual diseased and regenerative tubules become

enlarging foci, hyaline casts extend into the cortex, and eosinophilic droplets

may be seen in tubular epithelium (most prominently in males). Visible

glomerular changes develop at this time. Shortly, interstitial inflammation

(beginning at the cortical medullary junction) and fibrosis develops.1

End stage CPN is

characterized by involvement of the entire kidney and various effects in other

organs: hyperplasia of the chief cells of the parathyroid gland as well as

metastatic calcification in a number of organs, including the kidney, lung,

media of large arteries, and the gastrointestinal tract. An additional lesion

of end-stage CPN, which may be overlooked with the myriad and severe changes of

the glomeruli, tubules, and interstitium, is papillary hyperplasia of the

epithelium of the renal pelvis. This lesion consists of projections of

hyperplastic transitional epithelium containing large dilated vessels which

project into the pelvic lumen.1

Clinicopathologic findings in affected animals include marked proteinuria and

albuminuria and resulting hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hypercholesterolemia,

demonstrating the severity of the glomerular damage. Decreased functional

renal mass results in hyperphosphatemia, and serum calcium is decreased as a

result of Starling"s law as well as hypoalbuminemia. Serum nitrogen and

creatinine values increase only in late stages of the disease.1

References:

1. Seely JC, Hard GC, Blankenship B. Urinary Tract. In: Boormanâs Pathology of the rat: reference and atlas, 2nd edition, Suttie A, Leininger JR, Bradley AE, eds. London, Academic Press 2018; pp 135-137.

2. Hard GC, Banton MI, Bretzlaff RS, et al. Consideration of Rat Chronic Progressive Nephropathy in Regulatory Evaluations for Carcinogenicity. Toxicol Sci. 2013;132(2): 268-275.

3. Hard GC, Johnson KJ, Cohen SM. A comparison of rat chronic progressive nephropathy with human renal disease â implications for human risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009;39(4):332-346.

4. Hard GC, Khan KN. A Contemporary Overview of Chronic Progressive Nephropathy in the Laboratory Rat, and Its Significance for Human Risk Assessment. Toxicol Path. 2004;32:171-180.

5. Manskikh VN. Hypothesis: Chronic Progressive Nephropathy in Rodents as a Disease Caused by an Expanding Somatic Mutant Clone. Biochemistry Moscow. 2015;80(5):689-693.

6. Manskikh VN, Averina OA, Nikiforova AI. Spontangenous and Experimentally Induced Pathologies in the Naked Mole Rat (Heterocephalus glaber). Biochemistry Moscow. 2017;82(12):1504-1512.

7. Souza NP, Hard GC, Arnold LL, Foster KW, Pennington KL, Cohen SM. Epithelium Lining Rat Renal Papilla: Nomenclature and Association with Chronic Progressive Nephropathy (CPN). Toxicol Path. 2018;46(3):266-272.

8. Yamada N, Sato J, Kanno T, Wako Y, Tsuchitani M. Morphological Study of Progressive Glomerulonephropathy in Common Marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Toxicol Path. 2013;41:1106-1115.