Signalment:

Adult, male, eastern gray squirrel, (

Sciurus carolinensis).Three recuperating eastern gray squirrels were housed in an outdoor cage at a wildlife rehabilitation facility. Shortly after being fed a whole pumpkin, one was found dead, and the other two were ataxic, disoriented, and pawing the air. The pupils were dilated. The attending veterinarian began treatment with fluids, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (meloxicam), and an anti-convulsant (gabapentin). The neurologic signs did not improve with treatment and time. The squirrels were humanly euthanized, and a necropsy was performed.

Gross Description:

No gross lesions noted.

Histopathologic Description:

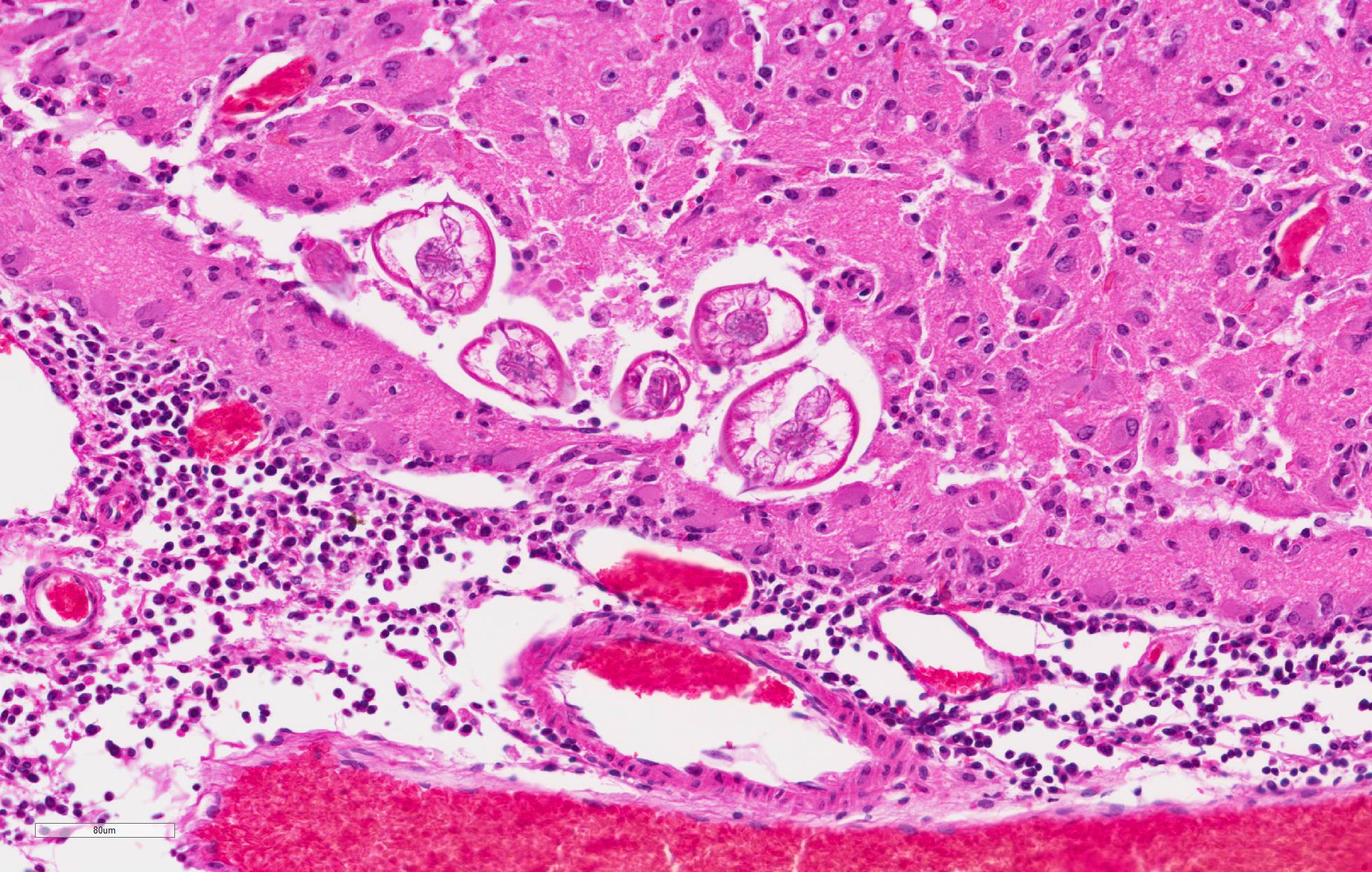

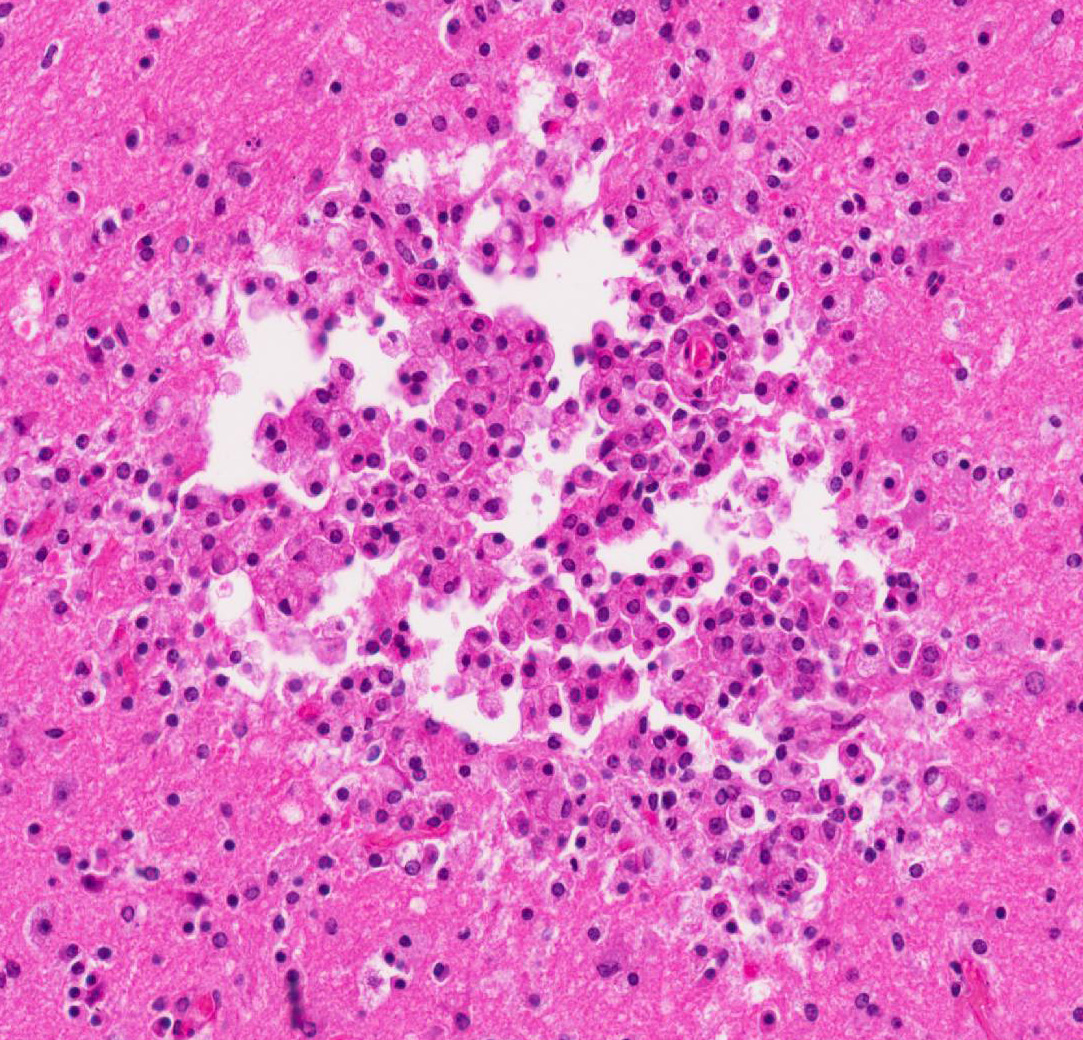

Cerebrum: Multifocally, there is necrosis of both gray and white matter characterized by disruption

and loss of neural tissue with replacement by moderate numbers of macrophages with vacuolated cytoplasm (gitter cells), lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and rare eosinophils. Scattered throughout the neural tissue are cross and tangential sections of larval nematodes. The larvae are 50 µm in diameter, have a 5 µm thick cuticle with lateral chords and alae, coelomyarianpolymyarian musculature, a pseudocoelom, and an intestine lined by uninucleate columnar cells with a brush border. Some larvae are associated with areas of necrosis and inflammation and some have no surrounding inflammation but are associated with adjacent vague linear tracks of necrosis and inflammation. Multifocally, throughout the section, there are moderate numbers of lymphocytes with fewer plasma cells and eosinophils expanding perivascular spaces and the meninges. There are moderately increased numbers of glial cells (gliosis) along with spheroids and numerous reactive astrocytes in affected areas.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, necrotizing and granulomatous, multifocal, marked, with perivascular cuffing, gliosis, astrocytosis, spheroids, and numerous larval nematodes.

Lab Results:

No laboratory analysis performed.

Condition:

Encephalitis/Baylisascaris procyonis

Contributor Comment:

The initial clinical suspicion was that these squirrels were suffering from a toxin which was

associated with the pumpkin. Examination of the enclosure revealed desiccated feces, which when evaluated by fecal floatation revealed the presence of ascarid eggs, consistent with Baylisascaris procyonis. Subsequently, histology of the brain provided the definitive diagnosis of neural larval migrans (NLM). B. procyonis is a member of the ascarid (roundworms) group of nematodes.

2 The raccoon (Procyon lotor) is the definitive host.

3 Dogs can also become infected with B. procyonis and shed eggs in feces.1 Raccoons become infected by consuming

B. procyonis eggs or intermediate hosts infected with larvae.

1,3 Larvae develop into adults in the raccoon intestine and produce large numbers of eggs which are shed in the feces.

3 Intermediate hosts ingest the eggs in environments contaminated with raccoon feces. In intermediate hosts, the larvae migrate through the body of the host. The third stage larvae of

B. procyonis can be up to 2 mm in length.

1

In most tissue, larvae are encapsulated in granulomas, however, in the brain encapsulation is slow to absent.

1 The large larvae migrate through neural tissue causing mechanical damage followed by an inflammatory response.

1,3 In this case, several larvae are present in neural tissue with no surrounding inflammation. Potentially, the pace of the migrating larva was faster than the immune response. Most inflammation present is associated with the migration tracks.

Eosinophils are a typical feature of parasiteinduced inflammation, but were less apparent in this case. There may have been some modulation of the immune response in this squirrel due to treatment. In this case, several larvae were present in the brain. However, even low numbers of larvae can result in severe pathology due to their large size and aggressive migration.

1,3 A variety of mammals and birds have been reported as intermediate hosts of B. procyonis.

3 B. procyonis NLM is also recognized as an important zoonotic disease which predominantly affects children who engage in pica.

1 The eggs of

B. procyonis can remain viable in the environment for years, even at below freezing temperatures.

3 The hardiness of the eggs and low infectious dose have even lead one investigator to speculate that B. procyonis could be utilized as a possible agent of bioterrorism.

5

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Encephalitis, necrotizing, granulomatous and eosinophilic, multifocal, moderate with perivascular cuffing, gliosis, and numerous nematode larvae, eastern gray squirrel,

Sciurus carolinensis.

Conference Comment:

This case

represents an excellent example of the characteristic eosinophilic and

granulomatous inflammation with linear necrotic tracts present in neural larval

migration of

Baylisascaris procyonis, a common ascarid nematode parasite

found predominantly in the Midwest, Northeast, and West Coastal United States.

7

As mentioned by the contributor, the raccoon is the definitive host and this

roundworm parasite typically does not cause clinical disease in this species.

6

The adult nematodes are confined to the small intestine of the definitive host;

however,

Baylisascaris procyonis neural, somatic (visceral), and

ocular

larval migration are well documented in humans and over 100 wild

and domestic animal species, including over 13 species of birds in North

America.1,3,6,7 In this case, the squirrel was likely exposed to

raccoon feces from its enclosure and accidentally ingested infective eggs. In

addition to raccoons, other species of have been reported to shed Baylisascaris

procyonis eggs in their feces, including dogs, kinkajous, and

skunks.3,6,7

Eggs

are infective about two weeks after they are excreted by the raccoon host, and

may persist in the environment for months to years. After the eggs are ingested

by an intermediate host, the

larvae hatch,

penetrate the intestinal wall, and then enter the portal circulation. After

passing into the arterial circulation, the larvae are distributed throughout

the body.5 A small number of larva enter the brain and aggressive

larval migration in predominantly the white matter of the brain and spinal cord

often leads to rapid debilitation, fulminant neurologic disease, and death of

the intermediate host.4,5 Humans, nonhuman primates, rodents,

rabbits, and birds are reported to be the most susceptible to neural larval

migrans.3 Other

Baylisascaris species include

B.

melis in badgers,

B. columnaris in skunks,

B. laevis in

woodchucks,

B. schroederi in pandas,

B. devosi in the American

pine marten, and

B. transfuga in bears. Any of the above mentioned

Baylisacaris

sp.

can

cause similar larval migration lesions if infective fecal eggs are ingested by

an intermediate or aberrant host.5,6

The conference

moderator noted that while in this case numerous cross sections of larva are

present and readily identified in the neuroparenchyma, most natural cases only

have subtle evidence of larval neural migration tracts without identifiable

larval cross sections. Additionally, the larva will continue to migrate after

the death of the animal, and migration tracts may not always have associated

inflammation and necrosis. There are currently no serologic tests commercially

available to distinguish active infection from prior exposure.7

Definitive diagnosis is based on identifying larva in histologic sections,

although a presumptive diagnosis is usually made by a combination of history,

clinical signs, and serologic testing.7

References:

1. Bauer C. Baylisascariosis: Infections of animals and humans

with 'unusual' roundworms. Vet Parasitol. 2013; 193:404-412

2. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey J. An Atlas of Protozoan

Parasites in Animal Tissues, 2nd ed. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology,

Washington, DC, 1998: 19-21.

3. Gavin PJ, Kazacos KR, Shulman ST:

Baylisascariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005; 18: 703-718

4. Kazacos KR. Baylisascaris procyonis and related

species. In: Samuel WM, Pybus MJ, Kocan AA, eds. Parasitic Diseases of Wild

Mammals. 2nd ed. Ames IA: Iowa State University Press; 2001:301-335.

5. Okulewicz A, Bunkowska K. Baylisascariasis: A new dangerous

zoonosis. Wiad Parazytol. 2009; 55:329-334

6. Santiago SD, Uzal FA, Giannitti F, Shivaprasad HL.

Cerebrospinal nematodiasis outbreak in an urban outdoor aviary of cockatiels (Nymphicus

hollandicus) in southern California. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;

24(5):994-999.

7. Sircar

AD, Abanyie F, et al. Raccoon roundworm infection associated with central

nervous system disease and ocular disease-- six states, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb

Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016; 65(35):930-933.