WSC 22-23

Conference 20

Case IV:

Signalment:

5 month-old, intact male, Labrador, Canis familiaris, canine

History:

This dog was presented to the emergency service of a veterinary clinic. Owners reported that he was alert in the morning and ate well. He suddenly became lethargic and they rapidly brought him to the clinic. On arrival, his temperature was elevated (39,4 ºC), but returned to normal values within an hour. He was in a lethargic state that gradually worsened. Blood parameters revealed only slightly decreased hematocrit (32) and potassium (3.4) values. Blood pressure was normal. He received intravenous fluids and intralipids, but his general state rapidly deteriorated and he was in cardiopulmonary arrest a few hours after his arrival at the clinic. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed unsuccessfully.

Gross Pathology:

The dog weighed 20 kg and was in good body condition. Lungs were diffusely edematous and the pericardial sac contained a small amount (5-6 ml) of blood-tinged fluid. The heart weighed 174 g (within normal values) and showed no anomaly. Approximately 20 to 25 ml of uncoagulated blood was present in the abdominal cavity. No lesion explaining this blood was found in the abdominal organs. The stomach was full of undigested dry food, amongst which two small blue particles (size of blueberries) were noted. No diarrhea was present. Considering the rapid onset of clinical signs and the fact the dog was healthy and up-to-date on his vaccination schedule, an intoxication was suspected.

Laboratory Results:

Routine bacteriological culture of the lung, liver and kidney revealed only rare hemolytic E.coli and few contaminants. A PCR for canine herpesvirus was negative. Stomach content was sent for toxicological analysis and results showed a large amount of phenethylamine detected by GCMS.

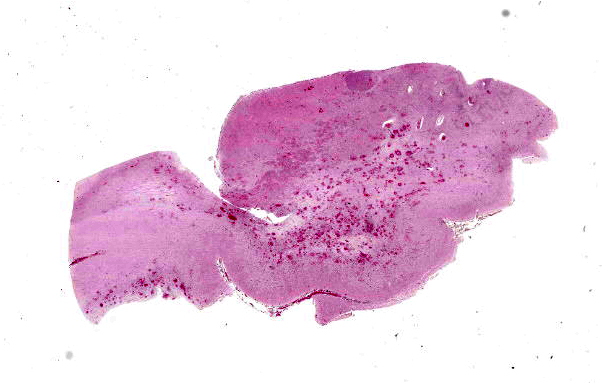

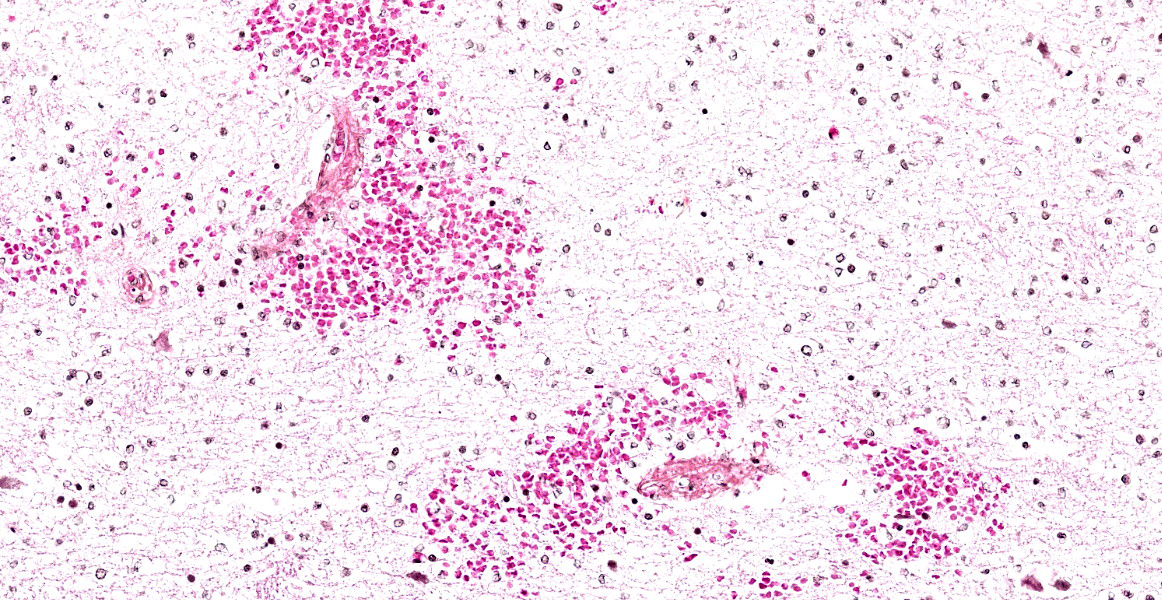

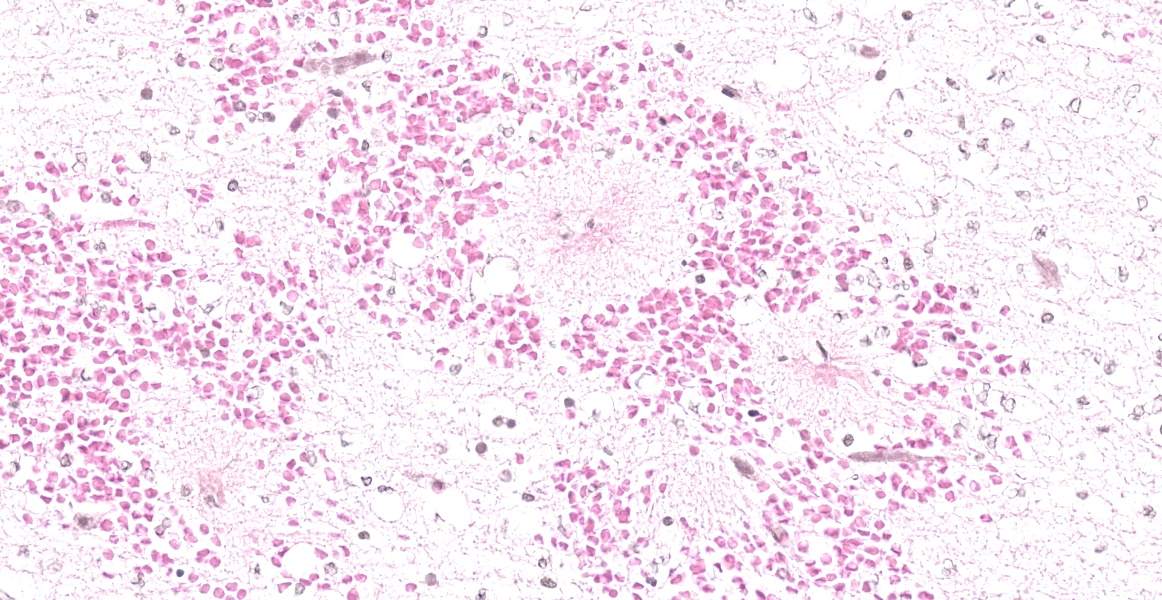

Microscopic Description:

Histological changes are limited to the cerebrum; they are multifocal, present in all lobes, but most severe in the right frontal lobe. There is marked and extensive vasogenic edema involving mainly the white matter, variably extending into the adjacent cerebral cortex, associated with vascular fibrinoid degeneration/necrosis and mostly perivascular hemorrhages. The wall of affected blood vessels is effaced by fibrinoid material, sometimes with pycnotic nuclei, and eryhrocytes and/or fibrin are present in the Virchow-Robin spaces. In affected areas, there are numerous reactive astrocytes and microgliocytes and, multifocally a few to several neutrophils. There are numerous microgliocytes/macrophages and occasional neutrophils in the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) and subarachnoidal spaces. Neuronal changes are interpreted as artefactual (“dark neurons”).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Marked and extensive vasogenic cerebral edema associated with vascular fibrinoid degeneration/necrosis and perivascular hemorrhages (mainly white matter)

Contributor’s Comment:

Phenethylamine is an organic compound, natural monoamine alkaloid, and trace amine, which acts as a central nervous system stimulant. It represents the core structure of numerous drugs with stimulant-like properties such as amphetamines and methamphetamines.8 It is also the major component of stimulant drugs used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) by improving brain levels of serotonin and norepinephrine.10 In the present case, the exact substance containing phenethylamine that was ingested by the dog could not be identified. The owners suspected that the dog had eaten an illegal substance, possibly from a neighbor’s gathering that took place the night before. To the best of their knowledge, the dog did not have access to other possible sources of phenethylamine-containing substances.

Very few reports have documented intoxication of dogs by amphetamines or by drugs prescribed for the management of AD/HD.2,4,9,11 The principal mechanisms of toxicity in amphetamine poisoning are the release of catecholamine with stimulation of the nervous system and a marked increase in the release of norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin. Clinical signs most commonly reported are cardiovascular signs such as hypertension and tachycardia and central nervous system signs such as hyperactivity, agitation and tremors. Hyperthermia is also often present. Lethargy, depression, and coma have been reported in the latter course of intoxication. Peak plasma concentrations of amphetamine occur 1-3 hours after ingestion.1 The median lethal dose (LD50) for orally administered amphetamine sulfate in dogs is 20 to 27 mg/kg.1 Full recovery can be achieved when a rapid diagnosis is made together with an aggressive intervention. In the present case, lethargy and depression were the principal clinical signs displayed. The very young age of the dog (4 months) and the presence of a large amount of phenethylamine as determined by GCMS analysis could have both contributed to the rapid deterioration of the animal leading to coma and death.

Histological lesions in the present case were present only in the brain and were centered around blood vessels (principally cerebral edema with a marked exudation of fibrin and perivascular hemorrhages). These changes are consistent with a significant increase in vascular permeability. In humans, it is generally assumed that death following a methamphetamine overdose results from heart attack or stroke. Central nervous system alterations are difficult to precisely determine in humans since polysubstance abuse is seen in the majority of cases.3 Arterial or venous infarcts and subarachnoid or parenchymal hemorrhages have been reported as neuropathological complications.5 A necrotizing vasculitis, predominantly of small blood vessels, but larger arteries and veins may be involved has also been observed in few cases.5

Recent studies using a rat model of acute methamphetamine intoxication showed the development of a temperature-dependent leakage of the blood-brain barrier and the development of vasogenic edema that could finally result in decompensation of vital functions and death. 6,7 More specifically, the authors found the leakage of albumin in the neuropil (reflecting alterations in vascular endothelium), an increased number of glial cells and the presence of several pyknotic neurons in rats that had received 9 mg/kg of methamphetamine.6,7 These changes were temperature dependent, being more severe in rats that were maintained under warm (29°C) compared to standard (23° C) ambient temperature. Histological changes in the brain of dogs following an intoxication by amphetamines have not been reported. However, the histological lesions observed in the present case are consistent with a severe alteration of the blood-brain barrier following intoxication with a phenethylamine-containing substance.

Contributing Institution:

Département de pathologie et microbiologie

Faculté de médecine vétérinaire

Université de Montréal

www.umontreal.ca

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Fibrinoid vascular degeneration and necrosis, acute, multifocal to coalescing, with, hemorrhage, edema, and gliosis.

JPC Comment:

Prior to reviewing the clinical history and gross necropsy findings of this case, the moderator and participants discussed possible differentials for fibrinoid vascular degeneration in the cerebrum of a dog, including infectious agents (i.e. endotoxemia, Rickettsia rickettsia, and Ehrlichia canis), accidental ingestion of illicit substances, and hypertension.

In a nine year retrospective study evaluating 241,261 cases of suspected poisoning events reported to the ASPCA’s Animal Poison Control Center in the United States, exposure to human medications accounted for 40% and 32% of canine and feline cases, respectively, and recreational or elicit medications accounted for 1.83% and 0.44% of exposures, respectively.12 Exposure to prescribed amphetamines and illicit methamphetamine comprised a small portion of these toxicities, accounting for 1.16% and 1.44% of total canine and feline exposures.12 Human pharmaceuticals more commonly referenced as a source of exposure included analgesics and medications treating CNS, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular disorders.12 These results indicate that amphetamine toxicity is an uncommon toxicosis in dogs and cats, but one that clinicians and pathologists should be cognisant of.12

Amphetamines are lipid-soluble drugs rapidly absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and which cross the blood-brain barrier.1 Clinical signs begin within 20 minutes of ingestion.1 Peak plasma concentration occurs within 3 hours, and, in dogs, the drug is cleared within 6 hours.1

Amphetamines continuously stimulate muscle activity causing energy depletion, calcium overload in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and constant muscle fasciculations, exacerbating energy demands.10 Rhabdomyolysis is a common consequence of amphetamine toxicosis in humans and is occasionally reported in dogs.1,10 Some cases may progress to myoglobinuria and acute kidney injury.10 Hyperthermia and respiratory failure can lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation, a potential cause of death in intoxicated dogs.1 Other reported cause of death include cerebral hemorrhage secondary to hypertension and heart failure.1 Metarubricytosis, hypersegmentation of neutrophil nuclei, and thrombocytopenia presumedly due to hyperthermia have been reported secondary to amphetamine toxicosis in a Boxer.13

References:

- Bischoff K. Toxicity of drugs of abuse. In: Gupta R, ed. Veterinary toxicology: basic and clinical principles. 3rd Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2007.

- Bischoff K, E. Beier 3rd and WC Edwards. Methamphetamine poisoning in three Oklahoma dogs. Vet Hum Toxicol 40: 19-20, 1998

- Büttner A. The neuropathology of drug abuse. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37(2):118-134.

- Diniz PP, Sousa MG, Gerardi Dg et al. Amphetamine poisoning in a dog : case report, literature review, and veterinary medical perspectives. Vet Hum Toxicol 2003:45:315-317

- Ellison D, Love S, Chimelli L, et al. A reference text of CNS pathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2013.

- Kiyatkin EA, Sharma HS. Acute methamphetamine intoxication: brain hyperthermia, blood-brain barrier and brain edema. Int Rev Neurobiol 2009;88:65-100.

- Kiyatkin EA, Sharma HS. Leakage of the blood-brain barrier followed by vasogenic edema as the ultimate cause of death induced by acute methamphetamine overdose. Int Rev Neurobiol 2019;146:189-207.

- Pei Y, Asif-Malik A, Canales AJ. Trace amines and the trace amine-associated receptor 1: pharmacology, neurochemistry and clinical implications. Neurosci. 2016;10: 1-17 (article 148).

- Pei Z, Zhang X. Methamphetamine intoxication in a dog: case report. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:139-145.

- Smith MR, Wurlod VA. Severe Rhabdomyolysis Associated with Acute Amphetamine Toxicosis in a Dog. Case Rep Vet Med. 2020;

- Stern LA, Schell M. Management of attention-deficit disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drug intoxication in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2018;48: 959-968.

- Swirski AL, Pearl DL, Berke O, O’Sullivan TL. Companion animal exposures to potentially poisonous reported to a national poison control center in the United States in 2005 through 2014. J Am Vet Med Ass. 2020; 257(5): 517-530.

- Wilcox A, Russell KE. Hematologic changes associated with Adderall toxicity in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2008; 37(2): 184-189.