Signalment:

Gross Description:

The kidneys are diffusely mottled maroon and pink and have slightly nodular surface. There is a small amount of clear watery fluid in the ventral lymph sacs and a large amount of similar fluid in the coelomic cavity. Coelomic fat bodies are large and slightly pink to tan.

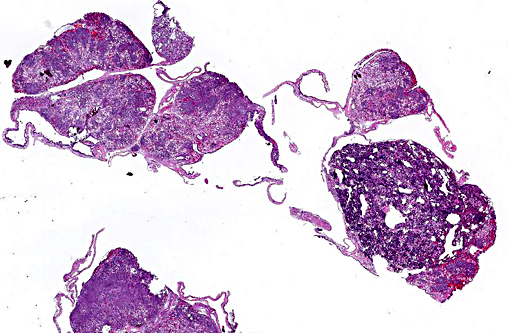

Histopathologic Description:

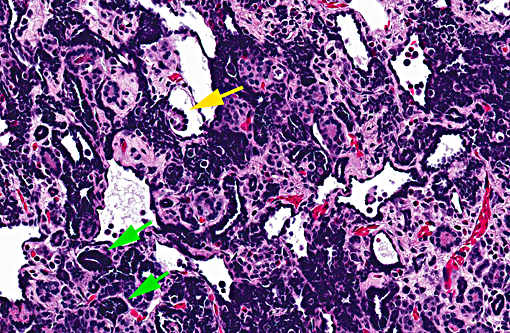

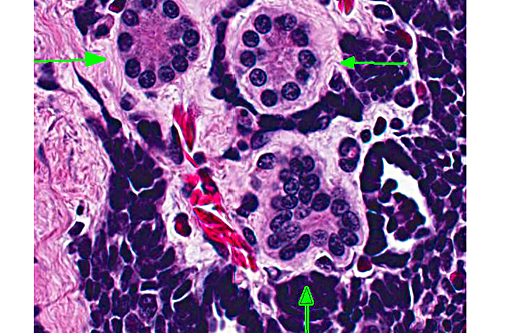

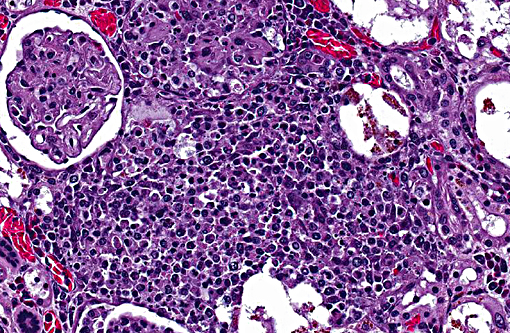

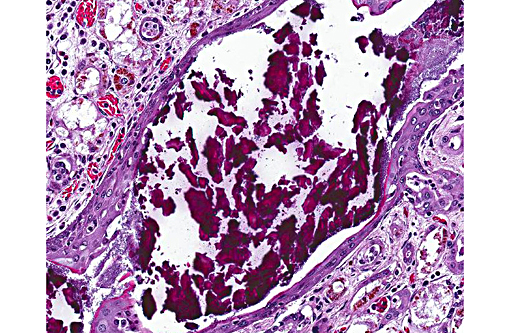

Kidney: There is a focal, unencapsulated, well-demarcated neoplasm composed of variably differentiated epithelial cells and blastemal cells set in a loose collagenous stroma. Blastemal cells have indistinct cell borders, scant to inapparent cytoplasm, and ovoid nuclei with hyperchromatic to finely stippled chromatin are present in dense clusters. Epithelial cells range from embryonal, with similar appearance to those above, forming ribbon-like strands and branching tubules, to more differentiated cuboidal to columnar cells forming mature, discrete tubules. These cells have distinct cell borders with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm that occasionally contains prominent granules. The nuclei are round to slightly ovoid, often basilar, with coarsely clumped chromatin. In some areas, tufts of cells protrude from primitive tubule walls into the lumen, resembling embryonic glomeruli. Mitotic figures are rare and only identified in blastemal populations. The stroma of this neoplasm is composed of loose aggregate of collagen interspersed with spindloid to wavy cells. The interstitium contains few granulocytes, lymphocytes and macrophages.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

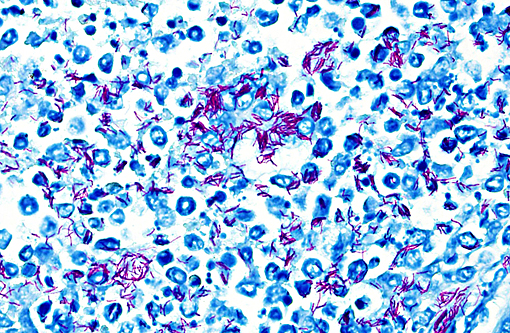

1. Kidneys and interrenal gland: Glomerulonephritis and adrenalitis, granulomatous, necrotizing, subacute, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with abundant intralesional acid-fast bacteria and renal architectural effacement

2. Kidney: Nephroblastoma

Lab Results:

Aerobic culture (skin wounds): Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aeromonas spp.

Anaerobic culture (skin wounds): Fusobacterium spp., Bacteriodes spp., unidentified Gram positive rods.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Mycobacteriosis in amphibians often presents as a disease of the integument, attributable to skin wounds and the organisms common presence in water. Multiple non-tuberculous Mycobacterium species have been reported to cause disease in amphibians, including M. marinum, M. chelonei, M. fortuitum, M. xenopi, M. abscessus, M. avium, and M. szulgai; M. marinum, M. xenopi and M. fortuitum are reported as the most common isolates.(6) Dissemination to multiple organs is a common feature of amphibian mycobacteriosis, and is grossly identified as pale nodules within the parenchyma or grey patches on mesothelial surfaces. Associated inflammation is typically described as granulomatous, although the nature of the infiltrate depends on the stage of infection and can range from a mixture of granulocytes and macrophages in more acute lesions to more typical granulomas with macrophages centrally and lymphocytes peripherally in chronic lesions.(1) In this individual, the most severe lesions were in the kidney and consisted of discrete, but otherwise disorganized granulomas, suggestive of a subacute time course. Renal severity may be directly related to the location of the skin wounds, as hindlimb lesions in amphibians have been reported to spread directly to the kidneys.(1)

In addition to disseminated inflammation throughout the kidneys, there was a large, focal, unilateral renal neoplasm. The morphologic appearance of this tumor was consistent with a nephroblastoma (e.g. Wilms tumor, embryonal nephroma). Classically, nephroblastomas consist of three embryonal cell populations. These include an epithelial component which forms irregular tubules and immature glomerular tufts, a mesenchymal component forming a loose stroma, and an undifferentiated blastemal component dispersed throughout the tumor.(4,5) Differentiation of the mesenchymal component into muscle, bone aand/or cartilage is common in some species, but has not been reported in amphibians. In this case, there were few glomerular structures and the tumor was pre-dominated by blastemal and epithetlial cells, and no differentiation of the mesenchymal amphibian nephroblastoma,(3) tubules in this case were variably differentiated, with some neoplastic tubular cells containing eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. In mammals, birds and reptiles, nephroblastomas arise from the metanephric blastema, either from neoplastic transformation during nephrogenesis, or from persistent nephrogenic rests.(5) In amphibians and fish, which throughout life, the tumor is thought to arise from mesonephric tissue. Rare in amphibians, nephroblastomas have been previously reported in an African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis), a fire-bellied newt (Cynops pyrrhogaster), a giant Japanese salamander (Andrias japonicus), and as an induced lesion in ribbed newts (Pleurodeles waltl).(2, 3) Nephroblastoma can be confirmed in humans and other mammals by immunohistochemical identification of Wilms tumor protein 1 within neoplastic cells. This has been attempted in amphibians in only one of the previously reported cases, and neither tumor cells nor internal controls were positive.(3) Immunohistochemistry was not pursued in this case.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Kidney, testis, and interrenal gland: Nephroblastoma.

2. Kidney: Nephritis, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with intra- and extracellular acid fast bacilli.

3. Collecting duct: Nephrolith.

Conference Comment:

In general mycobacteria can be classified into three groups: 1) Organisms that produce tubercles such as M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, 2) organisms that result in lepromatous inflammation such as M. leprae and 3) the atypical or non-tuberculous mycobacteria that may be opportunistic or primary pathogens; included in the third group are the mycobacterial organisms that infected the toad in this case. Many of the agents such as M. marinum, which is often the agent seen in amphibian infections, are zoonotic and can be important human pathogens in immunosuppressed and even non-immunosuppressed individuals. The organisms can be transmitted through direct contact with the animals or indirectly though the water.(7)

Internal organs commonly infected in amphibian mycobacteriosis include the liver, spleen, kidney as seen in this case, and intestines. Mycobacterial lesions may be misdiagnosed as lymphosarcoma in cases of amphibian mycobacteriosis but should be suspected in amphibians with granulomatous, lymphocytic or pyogranulomatous nodular inflammation in internal organs. Treatment is often ineffective and requires culling of affected individuals. Mycobacterial infections are not uncommon in captive amphibians and can infect a number of species. Infections are less common in reptiles but have been reported in snakes, lizards, turtles and crocodiles. Lesion locations in reptiles include the liver, lung, spleen, kidney, oral cavity, joints and subcutis. In snakes, lesions may be seen in the oral cavity and lungs; in lizards disease is more commonly reported to be disseminated; and in chelonians mycobacteriosis may include pulmonary, hepatic, plastron and skin lesions.(6)

References:

1. Green DE. Pathology of Amphibia. In: Wright KM, Whitaker BR, eds. Amphibian Medicine and Captive Husbandry. Malabar, FL, USA: Krieger Publishing Company; 2001:401-485.

2. Green DE, Harshbarger JC. Spontaneous neoplasia in amphibian. In: Wright KM, Whitaker BR, eds. Amphibian Medicine and Captive Husbandry. Malabar, FL, USA: Krieger Publishing Company; 2001:335-400.

3. Kawasumi T, Kudo T, UNE Y. Spontaneous nephroblastoma in a Japanese giant salamander (Andrias japonicus). J Vet Med Sci. 2012;74:673-675.

4. Maitra A. Diseases of Infancy and Childhood. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. Pathologic Basis of Disease, Eighth Edition. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:447-483.

5. Meuten DJ. Tumors of the Urinary System. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals, Fourth Edition. Ames, IA, USA: Blackwell Publishing; 2002:509-546.

6. Reavill DR, Schmidt RE. Mycobacterial lesions in fish, amphibians, reptiles, rodents, lagomorphs, and ferrets with reference to animal models. Vet Clin Exot Anim. 2012;15:25-40.

7. Bercovier H, Vincent V. Mycobacterial infections in domestic and wild animals due to Mycobacterium marinum, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. porcinum, M. farcinogenes, M. smegmatis, M. scrofulaceum, M. xenopi, M. kansasii, M. simiae and M. genavense. Rev sci tech Off Epiz. 2001;20(1):265-290.