Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 6, Case 1

Signalment:

Two year and nine month-old, male castrated, mixed breed, canineThree year-old, male intact, Golden retriever, canine

Eight year-old, male castrated, mixed breed, canine

Fifteen year-old, male castrated, Labrador, canine

History:

Gross Pathology: Segmental hemorrhagic necrosis of the bowl with perforation and peritonitisLaboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

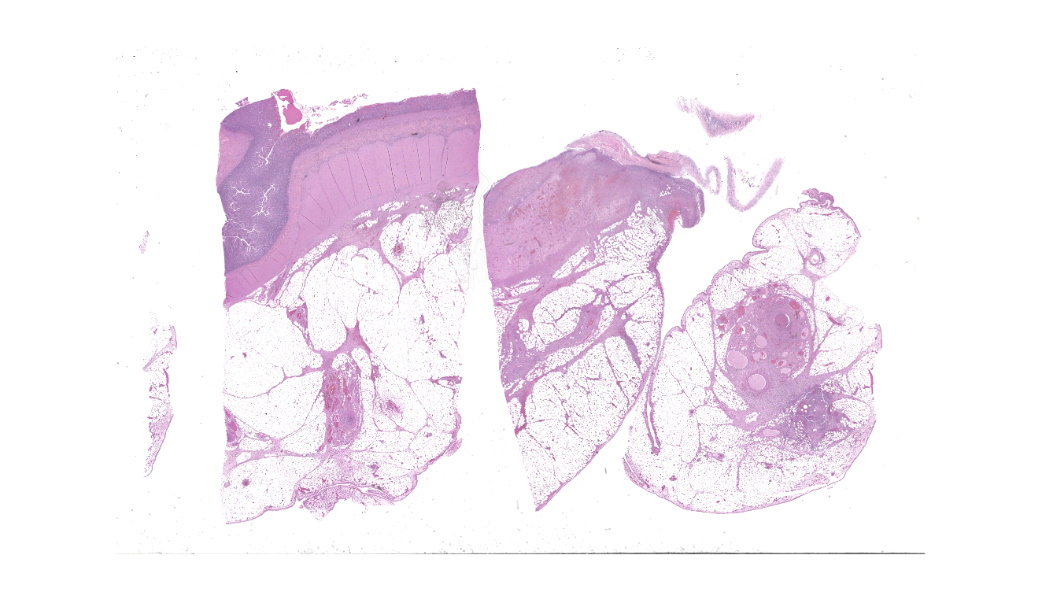

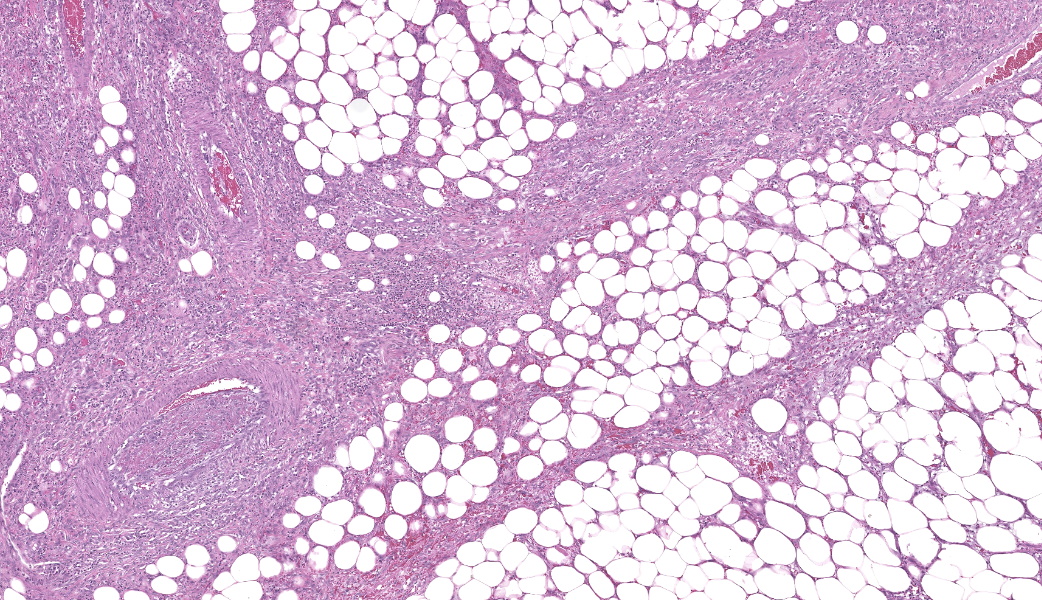

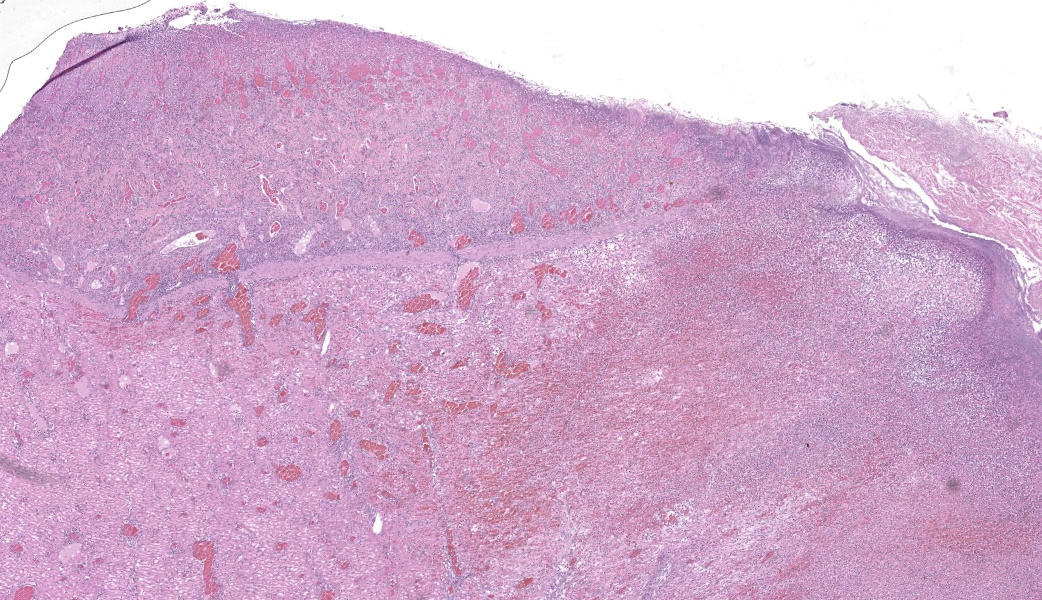

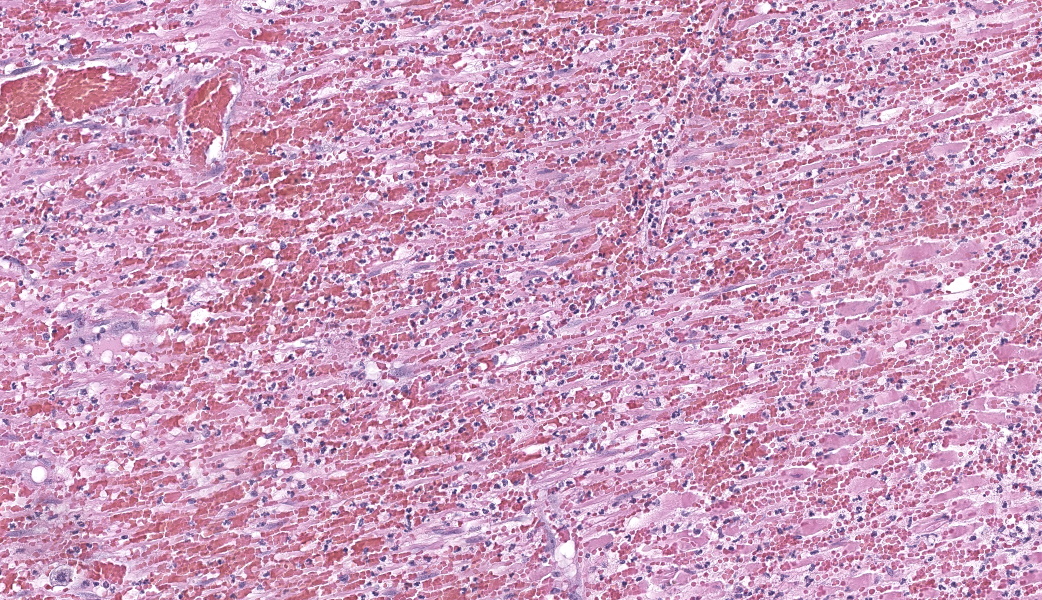

Findings are very similar in all cases that were submitted to the diagnostic laboratory.In all samples from the grossly discolored and swollen segment there was transmural necrosis of the intestine with extensive hemorrhage extending into the mesenteric fat. In the adjacent viable intestine there was eosinophilic infiltration of variable intensity. There was multifocal necrosis of mesenteric fat and, in some sections, diffuse eosinophilic infiltration. Large vessels were dilated and many contained thrombi.

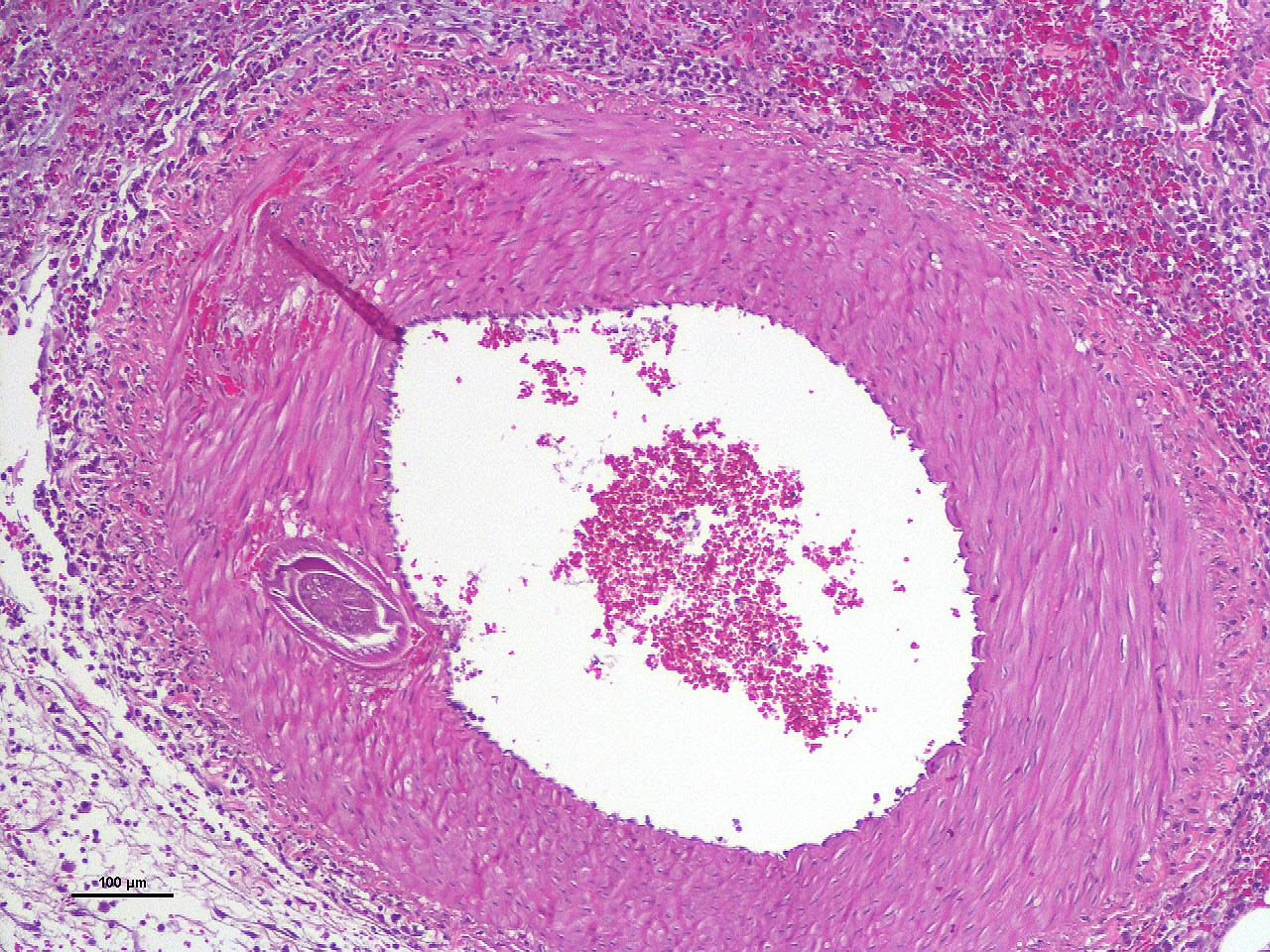

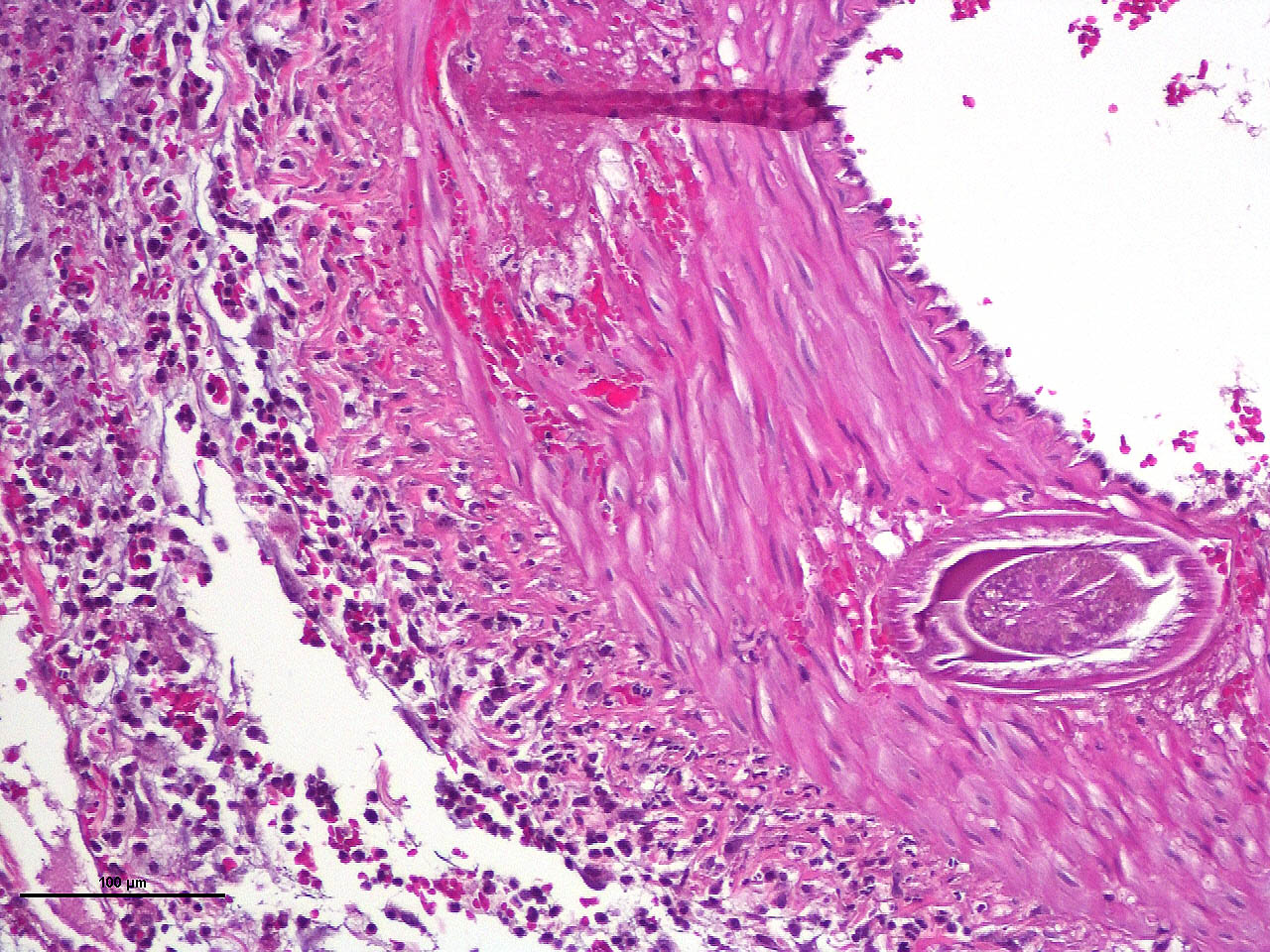

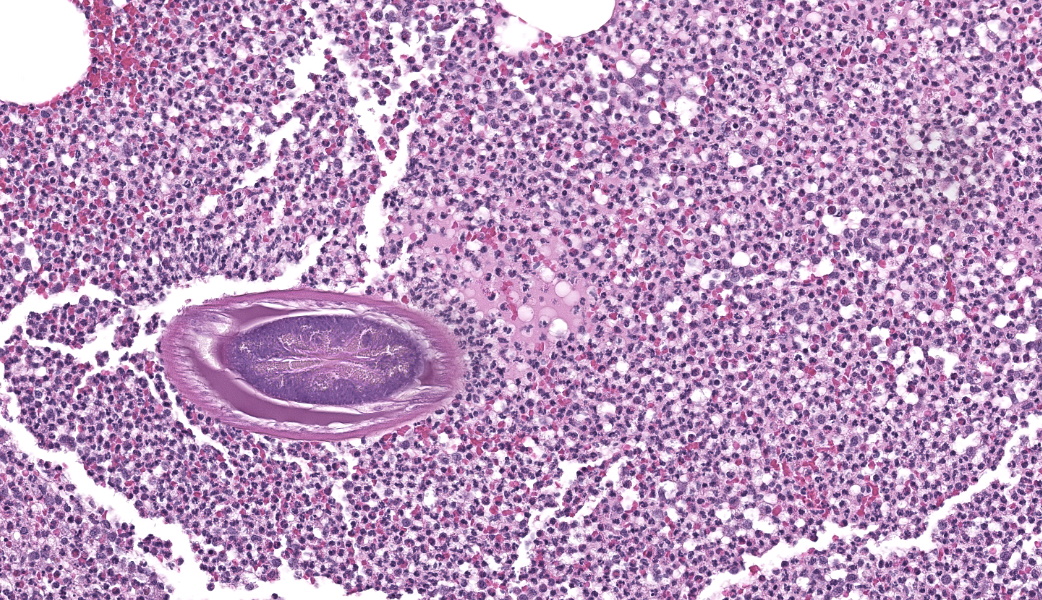

Within the media of medium to small sized arteries there were sections (not present in all slides due to the small size of the parasite – but see photomicrographs) of a nematode larva, approximately 100-200 µm in diameter with lateral allae and central digestive tract. These features are consistent with a spirurid of which Spirocerca is the most likely in our region. Foci of necrosis with hemorrhage were observed in the media of some arteries, where no larvae were identified.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Acute transmural necrotizing eosinophilic enteritis and eosinophilic peritonitis with arterial mesenteric thrombi and rare intralesional nematode larvae (spirurid)Contributor's Comment:

Several cases of this condition were diagnosed in the last few years in Israel, where incidence of Spirocerca infection is high.1,7 We have not observed breed or age predilection. The presenting history is usually that of intestinal infarction, with or without peritonitis. Clinical DDs are volvulus or intussusception.Heavy eosinophilic infiltration of mesenteric fat and thrombi are a common histologic finding in all samples in addition to acute transmural intestinal necrosis. In only a few of the samples intralesional larvae have been observed.

Some samples with similar history which were received in the past, before we became aware of this condition, were evaluated retrospectively. Although no parasites were found, we considered the presence of heavy eosinophilic infiltration and thrombi to be highly suggestive of aberrant larval migration of Spirocerca. Follow up information was available for some of these dogs. The vets described recurrent intestinal infarction and peritonitis with or without perforation.

Spirocerca lupi is a spirurid nematode that parasitizes the esophageal wall of dogs and other carnivores. It is most common in warm climates where beetles act as intermediate hosts.1,2,7 The normal site for the adult nematode is the distal region of the esophageal submucosa or the proximal stomach, where they are found in a cystic granulomatous lesion.2

Third stage larvae of Spirocerca are ingested with beetles and penetrate the gastric mucosa. They move along arteries to the aorta and migrate in its wall to the thoracic region where they are found several weeks after ingestion. They incite granulomatous inflammation in the aorta and stay there for 2-4 months. Later, the larvae migrate to the esophagus where they mature in the submucosa and perforate the epithelium.2,7

Larvae that follow aberrant migratory pathways may be found in granulomas in subcutaneous tissue, bladder, kidney, spinal cord and intrathoracic locations.2,3,9 To our knowledge, there are no descriptions of Spirocerca in mesenteric blood vessels.

Aortic lesions associated with Spirocerca include intimal and medial hemorrhage and necrosis with eosinophilic inflammation, thrombus formation and rarely rupture of the aortic wall.1,2,7

Contributing Institution:

The Weizmann Institute of Science http://www.weizmann.ac.il/JPC Diagnoses:

- Mesentery: Arteritis and periarteritis, necrotizing and eosinophilic, chronic, multifocal, severe, with arterial thrombi and rare larval spirurids.

- Small intestine: Enteritis and peritonitis, necrotizing and eosinophilic, chronic, regionally extensive, severe.

JPC Comment:

The JPC’s own MAJ Katie Scott moderated Conference 6 and took participants on a journey of cases from around the world; each one was from somewhere outside of the continental U.S., highlighting the truly global nature of the WSC and the importance of international contributions to pathology education. This first case provided an excellent opportunity to review of the pathogenesis and life cycle of Spirocerca lupi, both of which are well-covered in the contributor’s comment. Additionally, the lesions of spirocercosis that are considered pathognomonic in the dog were covered and include aortic scarring with aneurysms, thoracic spondylitis, and caudal esophageal nodules. Special attention was paid to the chronic arterial thrombi present in numerous arteries in this case, which are a classic part of the pathogenesis of this parasite due to its arterial migratory routes and chronic intimal irritation. Participants were also reminded of the importance of specifying what type of vessels (arteries, arterioles, veins, lymphatics, etc.) are affected when giving a description, as this can provide important clues towards pathogenesis of some diseases that may preferentially affect a specific vessel type.Spirocerca lupi is one of a handful of helminths that are classified as Group I carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) due to the well-documented malignant transformation of S. lupi esophageal nodules into esophageal fibrosarcomas or osteosarcomas in up to 25% of infected dogs.6 Less commonly, chondrosarcomas or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas can also be seen.6 Metastasis to multiple locations throughout the body, including the lungs, kidneys, stomach, spleen, heart, and tongue, occurs frequently.6,7 Significantly higher levels of interleukin-8 (IL-8) have been documented in dogs with malignant esophageal nodules.4 IL-8 is released by activated fibroblasts in pre-neoplastic nodules and is chemotactic for neutrophils. IL-8 is also involved in the tumor progression of human herpesvirus-4 (Epstein–Barr virus)-induced carcinomas.4

Other unwanted guests that no one invited to the party due to their classification as Group I carcinogens include Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrine, and Schistosoma haematobium. Clonorchis sinensis, a liver fluke transmitted via ingestion of undercooked fish hosting the parasitic metacercariae, can induce hepatocellular carcinomas or cholangiocarcinomas via mechanical damage to bile duct epithelial cells and suppression of biliary epithelial apoptosis via a wide range of excretory and secretory products (ESP).6Opisthorchis viverrine, another liver fluke ingested from raw fish, also induces cholangiocarcinoma through similar mechanisms to C. sinensis. Schistosoma haematobium, another trematode, causes squamous cell neoplasms within the urinary bladder and is the only human schistosome directly associated with cancer. S. japonicum and S. mansoni are also classified as carcinogens, but as Groups 2B and 3, respectively.6

Yet another parasite within veterinary species that is well-known to induce malignant neoplasms is Cysticercus fasciolaris, the larval form of the cestode Taenia taeniaformis. This larval tapeworm can induce the formation of fibrosarcomas in the liver of infected rats.5 There is a short list of additional parasites associated with the development of neoplasia, but the body of literature has not yet established a direct causal link between these neoplasms and the parasites themselves. These include: Trichosomoides crassicauda, the urinary bladder threadworm of rats that, although not directly carcinogenic in and of itself, is associated with the development of urothelial carcinomas via the creation of a chronically irritated environment within the urinary bladder that may be more receptive to the effects of external carcinogens; Heterakis gallinarum and H. isolonche, cecal nematodes of avian species, induce granulomatous nodule formation that can eventually progress to leiomyomas; and Trichuris muris, an intestinal-dwelling nematode of mice, can induce chronic cecal irritation that can develop into intestinal neoplasms.5,8 Keeping these tiny not-friends on a short list of carcinogenic or cancer-associated parasites is crucial to the pathologist’s differentials list when faced with cases where their consideration is warranted.

References:

- Aroch I et al. Spirocercosis in dogs in Israel: A retrospective case-control study (2004-2009). Vet Parasitol. 2005;211:234-40.

- Brown CC et al. Alimentary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 5th edition; Maxie MG ed., Academic Press, Inc. Vol 2, 2007 pp. 97-98.

- Du Plessis CJ et al. Aberrant extradural spinal migration of Spirocerca lupi: four dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48:275-8 (2007).

- Long X, Ye Y, Zhang L, Liu P, Yu W, Wei F, Ren X, Yu J. IL-8, a novel messenger to cross-link inflammation and tumor EMT via autocrine and paracrine pathways (Review). Int J Oncol. 2016;48(1):5-12

- Mahesh Kumar J, Reddy PL, Aparna V, Srinivas G, Nagarajan P, Venkatesan R, Sreekumar C, Sesikaran B. Strobilocercus fasciolaris infection with hepatic sarcoma and gastroenteropathy in a Wistar colony. Vet Parasitol. 2006;141(3-4):362-7.

- Porras-Silesky C, Mejías-Alpízar MJ, Mora J, Baneth G, Rojas A. Spirocerca lupi Proteomics and Its Role in Cancer Development: An Overview of Spirocercosis-Induced Sarcomas and Revision of Helminth-Induced Carcinomas. Pathogens. 2021;10(2):124.

- Sasani F et al. The evaluation of retrospective pathological lesions on spirocercosis (Spirocerca lupi) in dogs. J Parasit Dis. 2014;38:170–173.

- Serakides R, Michel AF, de Lima Santos R, and Silva SM. Proliferative and inflammatory changes in the urinary bladder of female rats naturally infected with Trichosomoides crassicauda: Report of 48 cases. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2001;53(2).

- Tudury EA et al. Spirocerca lupi-induced acute myelomalacia in the dog. A case report. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci. 1995;32:22.