CASE 1: F4/19 (4136413-00)

Signalment:

10-week-old female domestic pig, mixed breed, Hampshire/Yorkshire/Landrace, Sus scrofa domesticus

History:

Previously healthy pig that suddenly developed dyspnea and became lethargic. Its ears and snout were cyanotic. The pig was euthanized the same day as clinical signs appeared and submitted for necropsy.

The farm at which the pig was raised was a piglet producer with approximately 360 sows. Lately they had had several pigs showing similar kind of symptoms.

Gross Pathology:

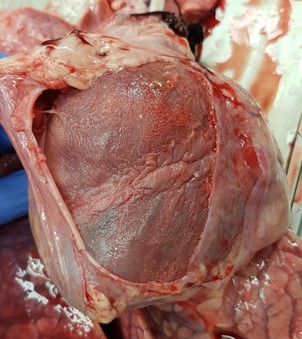

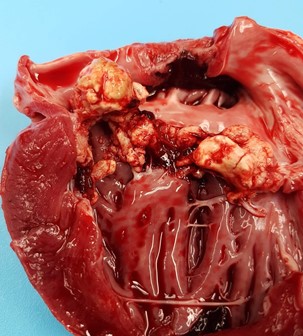

Bilaterally the pinna and the snout were cyanotic. Main findings were located to the thoracic cavity, which contained approx. 1 dl of clear yellow tinted fluid with gelatinous proteinaceous material. The visceral and parietal surfaces of the pericardium were diffusely covered by a thin layer of fibrinous exudate. The heart was moderately enlarged with a moderate hypertrophy of the left ventricular wall. The entire left atrioventricular valve was covered by multiple, raised, irregularly shaped, pale light yellow-gray, friable vegetations ranging from 1 mm in diameter to 2 x 2 x 1 cm in cross section.

In the renal cortices bilaterally, there were multifocal pale foci, approximately 2-10 mm in diameter.

Laboratory results:

Growth of Streptococcus suis in pure culture from sample taken from the left atrioventricular valve.

Microscopic description:

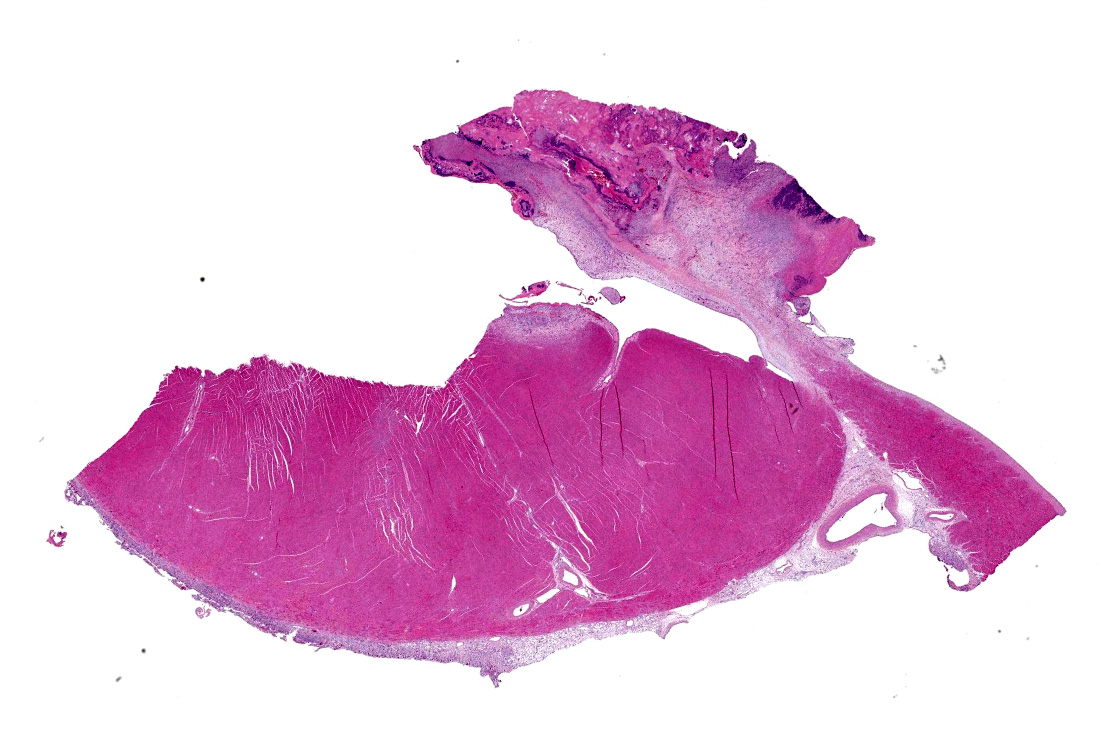

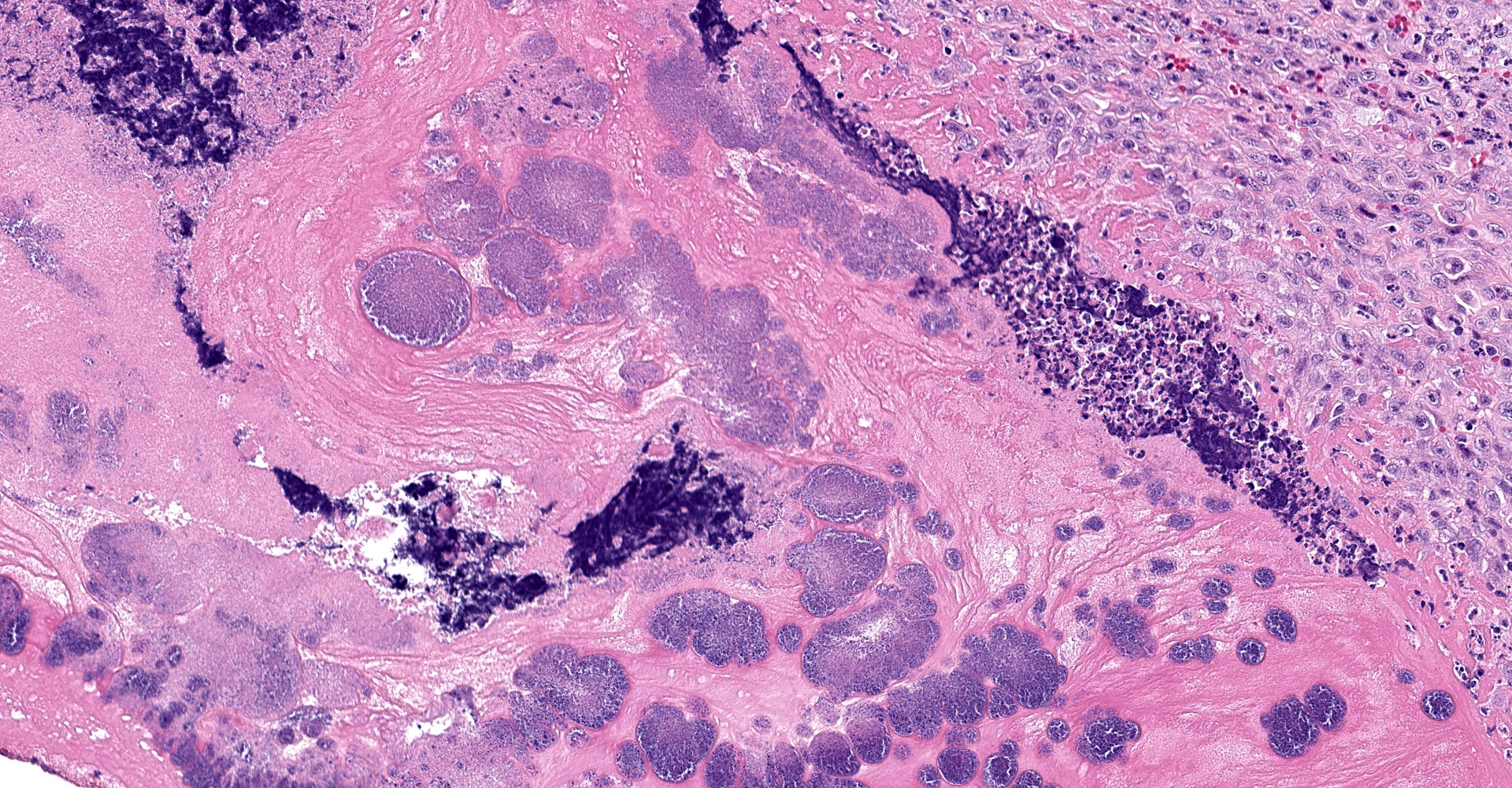

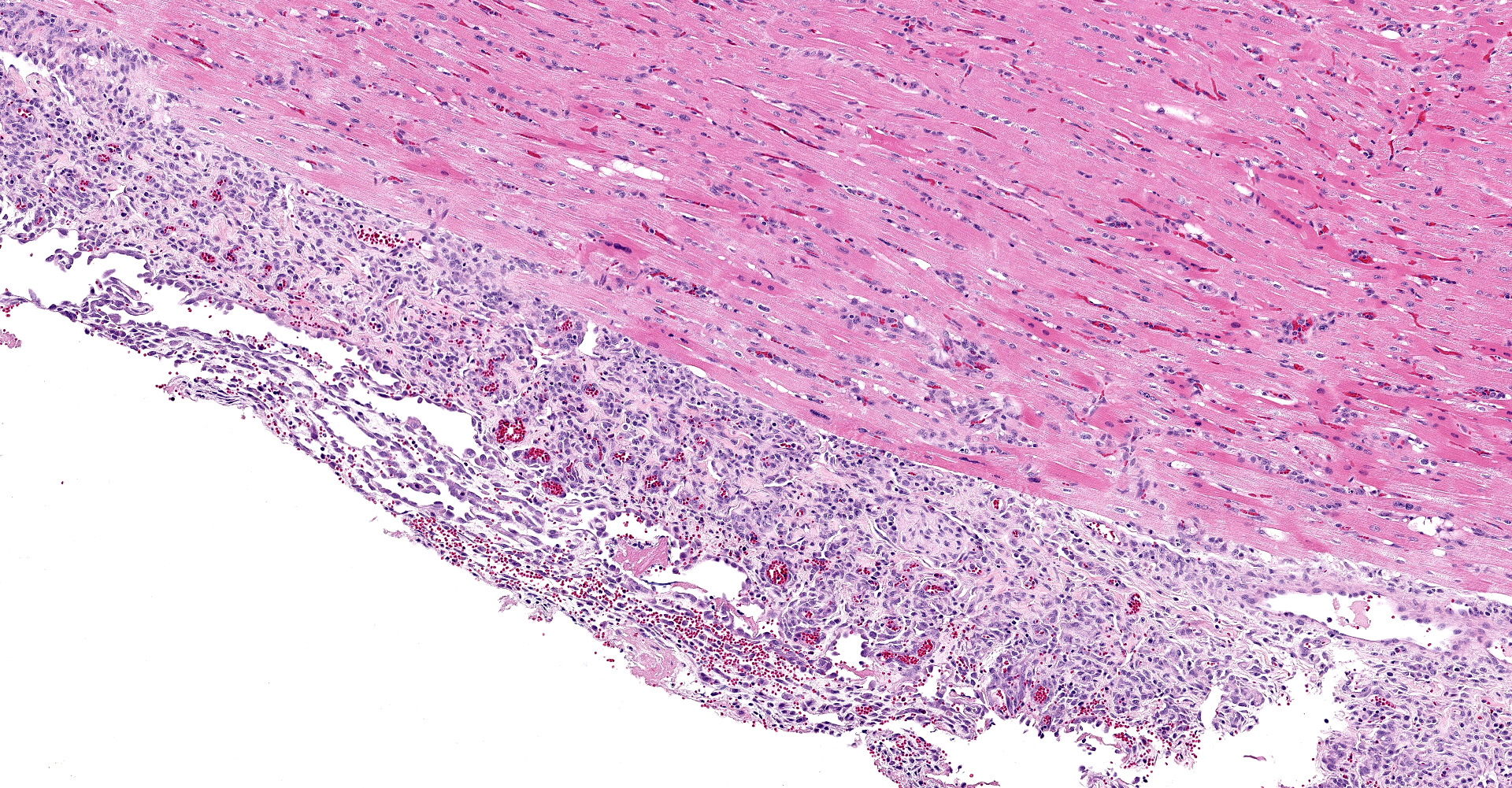

The atrioventricular valve is expanded and replaced by an excessive accumulation of pleomorphic and plump spindle-shaped cells (reactive fibroblasts), loose collagen strands and small vascular structures outlined by plump endothelial cells (angiogenesis) (granulation tissue), and in multiple areas, both on the valve surface as well as in the center, there are large deposits of brightly eosinophilic amorphous material (fibrin). In the deposited fibrin there are multiple separate round foci and larger coalescing areas of coccoid bacteria. Multifocal in the border between granulation tissue and fibrin there are moderate to large aggregates of degenerative and non-degenerative neutrophils. Scattered within the granulation tissue are mild to moderate infiltrates of mixed inflammatory cells, dominated by macrophages with lesser amounts of neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Focally, affecting the endocardial and subendocardial tissue of the opposing left ventricular wall there is a similar inflammatory lesion as described above with addition of a minor acute hemorrhage. In this region there is also mild infiltration of mixed inflammatory cells disrupting Purkinje fibers and separating cardiomyocytes.

In the myocardium there is an additional focal area with reactive fibroblasts, mild infiltration with mononuclear cells and cardiomyocytes with hypereosinophilic clumped sarcoplasm, some with small hypercondensed (pyknotic) nucleus (myocardial necrosis). The subepicardial tissue is markedly thickened by a similar inflammatory lesion dominated by granulation tissue with multifocal surface fibrin deposits.

In the ventricular wall of some sections there is an intravascular aggregate of hypereosinophilic amorphous material (fibrin), focally containing coccoid bacteria, attached to the endothelium (thrombus).

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Heart: Pancarditis, fibrinosuppurative, multifocal to coalescing, severe, chronic, with granulation tissue and intralesional coccoid bacteria.

Contributor's comment:

In swine bacterial endocarditis is a common lesion, and usually detected at postmortem inspection of slaughter pigs. Bacterial endocarditis in swine typically manifests as vegetations involving the cusps of the left atrioventricular valve.6,9 In acute bacterial endocarditis Streptococcus suis is the most commonly found bacteria.8 Apart from Streptococcus suis, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathie is an important etiologic agent, but the disease can also be caused by infection with other opportunistic bacteria such as Pasturella multocida, Trueperella pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as other Streptococcus spp.8,9

Worldwide, Streptococcus suis is an important swine pathogen, causing septicemia and acute death, meningitis, polyarthritis, polyserositis and valvular endocarditis, typically in 5?10-week-old pigs.4 The bacteria have zoonotic potential and in 2014 there were estimates of over 1600 confirmed human cases of Streptococcus suis reported in over 30 countries.3 Streptococcus suis can be found in clinically healthy pigs as a part of the normal bacterial flora in the upper respiratory tract. In diseased pigs Streptococcus suis isolates typically belong to serotypes 1-9, with serotype 2 being considered to be the most common and virulent subtype in Euroasian countries, and that subtype is also responsible for the majority of human cases.4

Bacterial valvular endocarditis arises in animals with a sustained or recurrent bacteremia. It is thought to occur either by adherence of blood borne bacteria to a sterile thrombus on a valve with a damaged endothelium, or by bacterial colonization beginning in the capillaries of the valve during septicemia.7,9,11

Emboli from valvular endocarditis can cause secondary lesions in other organs. Left sided lesions give rise to systemic infarcts, nephritis and myocarditis among several possible sequela, while emboli arising from a lesion on the right side most often leads to complications involving the lungs, such as infarcts, abscesses or pneumonia.11

Contributing Institution:

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; Department of Biomedical Science and Veterinary Public Health; Pathology Unit

JPC diagnosis:

Heart, left ventricle and AV valve: Valvular and mural endocarditis and epicarditis, fibrinosuppurative, focally extensive, severe, with granulation tissue and numerous colonies of cocci.

JPC comment:

Streptococcus suis is a capable bacterium, with a wide array of virulence factors that enable infections at various sites in pigs and humans. It expresses various adhesins, such as fibronectin-binding protein, enolases, a dipeptidyl-peptidase-4, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and others, which allow for efficient attachment to host cells or extracellular components like collagen, fibrinogen, or fibronectin. Though more likely in non-encapsulated strains, S. suis can form a biofilm when in the presence of fibrinogen. The expression of suilysin, a cytotoxic hemolysin, likely enables destruction of epithelial cells and allowing S. suis to progress past the epithelial barrier. From recent research, suilysin affects the proteins of tight junctions, and alters the distribution of occludin and zona occludens-1 in tracheal epithelial cells.2 The polysaccharide capsule is one of the most important virulence factors, as it inhibits phagocytosis my neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and monocytes, as well as allowing for intracellular survival. S. suis has the capacity to degrade chemokines such as CCL5 and IL-8, decreasing signaling for phagocytes. It also has the ability to interact with the complement system by binding Factor H, potentially decreasing or removing an important regulatory component that limits the pro-inflammatory response, which can be injurious to the host. Also, in the arsenal of virulence factors include several DNases, which help S. suis evade neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs).5

The extent to which S. suis alters the complement pathway is only recently becoming clear, with the recent identification of an IgM degrading enzyme, designated IdeSsuis. IgM is an approximately 1000 times more potent activator of the classical complement cascade than IgG, with IgM being the first class of antibodies produced in response to antigenic stimulation. By preventing early opsonization by IgM and activation of the complement cascade, the bacterium has opportunity to replicate and cause increased host tissue damage.10

Often, non-encapsulated S. suis isolates are obtained from the heart of pigs at slaughterhouses and are considered incidental findings. These bacteria are generally considered avirulent. Most of these strains have a mutation in the capsule gene (cps), and while the capsule does not form, the expressed adhesins are more easily able to attach to host cells of the heart. However, inoculation of mice with an acapsular isolate with subsequent culture and passage to new mice allowed S. suis to regain the ability to produce a capsule. The bacteria cultured and tested in vitro did not demonstrate this ability, suggesting the host microenvironment is critical for S. suis to repair and/or alter its virulence genes.1

There is mild slide variation, and the scanned slide has a focus of basophilic material, posited to be mineral. While not performed in this case, additional stains could have helped determine the composition of the material. Von Kossa stains stain mineral, but not specifically calcium. Alizarin red stain would be an appropriate stain to correctly identify calcium mineralizations, if available.

References:

- Auger JP, Meekhanon N, Okura M, et al. Streptococcus suis serotype 2 capsule in vivo. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2016;22(10):1793-1796.

- Bercier P, Gottschalk M, Grenier D. Streptococcus suis suilysin compromises the function of a porcine tracheal epithelial barrier model. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2020;139: 103913.

- Feng Y, Zhang H, Wu Z et al. Streptococcus suis infection. An emerging/reemerging challenge of bacterial infectious diseases? Virulence 5(4):477-497, 2014

- Gottschalk M, Segura M. Streptococcosis. Zimmerman JF, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, Zhang J, eds. In Diseases of Swine, 11th ed. Hoboken, USA: John Wiely & Sonc Inc; 2019: 934-950

- Haas B, Grenier D. Understanding the virulence of Streptococcus suis: A veterinary, medical, and economic challenge. Med Mal Infect. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2017.10.001

- Jensen HE, Gyllensten J, Hofman C et al. Histologic and bacteriologic findings in valvular endocarditis of slaughter-age pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest 22:921-927, 2010

- Järplid B, Brennius E, Nilsson NG. Observations of apparent early valvular endocarditis in swine. J Vet Diagn Invest 9:499-451, 1997

- Katsumi M, Kataoka Y, Takahasi T et al. Bacterial Isolation from Slaughtered Pigs Associated with Endocarditis, Especially the Isolation of Streptococcus suis. J Vet Med Sci 59(1):75-78, 1997

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of domestic animals. 6th ed. St Louis, USA: Elsevier; 2016; Vol 3:30-33.

- Rungelrath V, Weibe C, Schutze N, et al. IgM cleavage by Streptococcus suis reduces IgM bound to the bacterial surface and is a novel complement evasion mechanism. Virulence. 2018;9(1):1314-1337.

- Thiene G, Basso C. Pathology and pathogenesis of infective endocarditis in native heart valves. Cardiovasc Pathol 15:256-263, 2006