Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 9, Case 4

Signalment:

Six day-old piglet, male, cross-breed (Sus scrofa domestica)History:

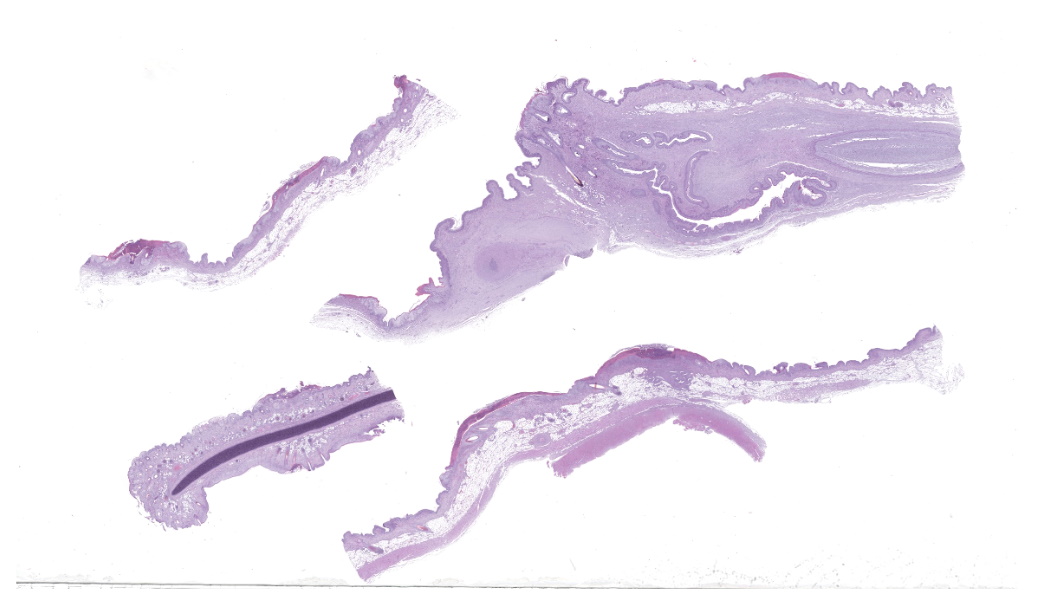

Gross Pathology: Six-day-old piglet of 1.16 kg weight with poor body condition and prominent bone protuberances. In a multifocal to generalized pattern throughout the skin and tongue, there were circular 0.1 to 0.5 cm in diameter lesions characterized by slightly prominent, firm, and well circumscribed aspect (papules and pustules); most of them were brownish in color with central umbilication and crusted. Significant lesions were not found in internal organs or in the subcutaneous tissue.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

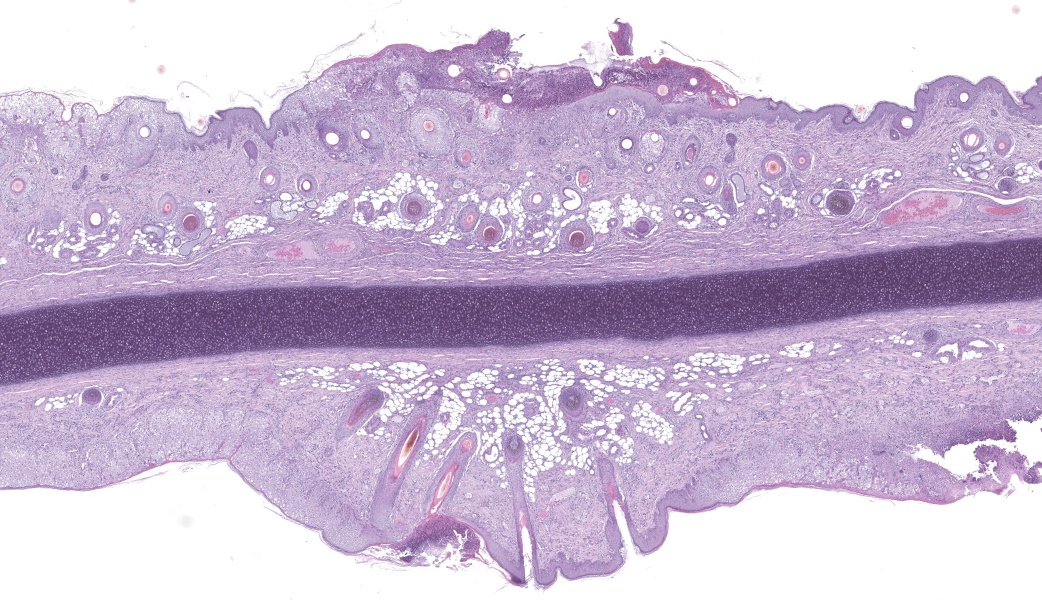

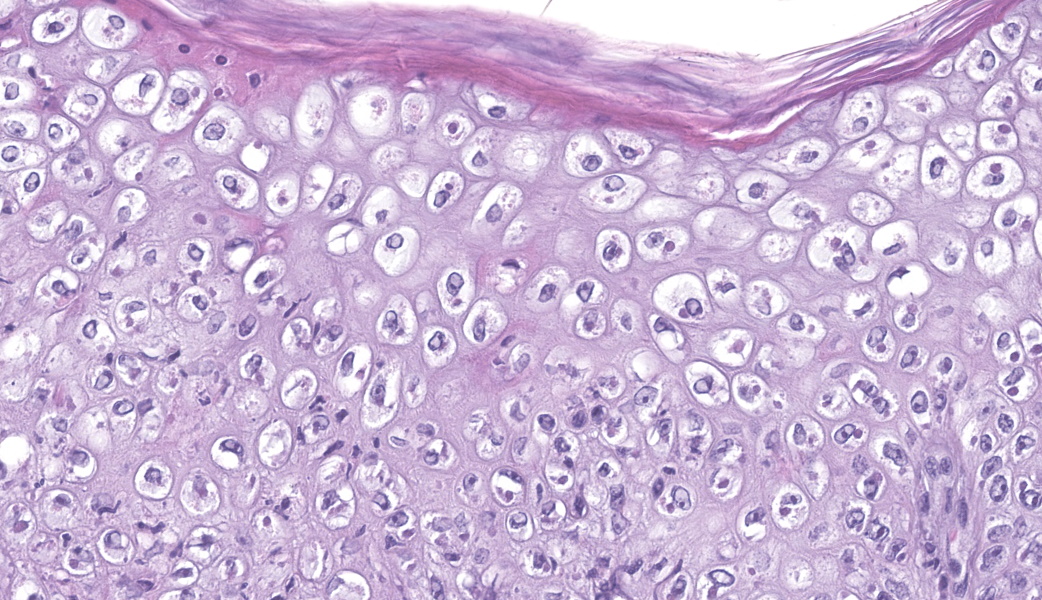

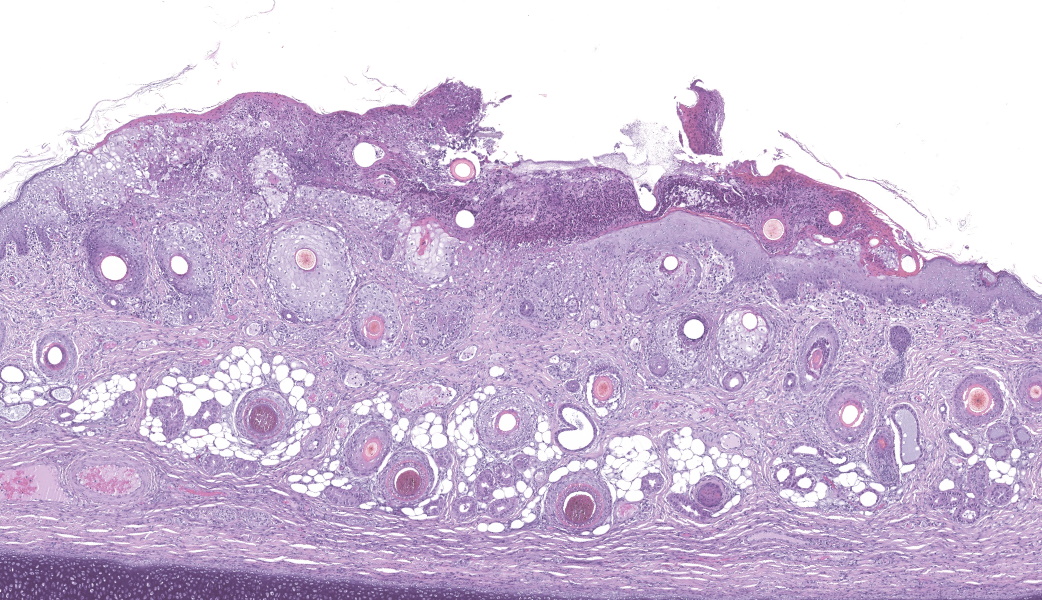

Haired skin (ear, prepuce, and inguinal area): affecting 20% of the evaluated section there is a proliferative and necrotizing process that mainly affects the epidermis. The epidermis and hair follicle epithelium show the following features: stratum corneum with diffuse mild compact hyperkeratotic orthokeratosis with multifocally serocellular crusts composed by cellular debris, degenerated keratin, degenerated neutrophils, and multiple superficial coccoid bacterial colonies (secondary contamination). Also, stratum spinosum shows multifocal marked thickening (acanthosis), and numerous keratinocytes display ballooning degeneration and intracytoplasmic perinuclear 2-5 ?m eosinophilic inclusion bodies. Multifocally, in the most affected areas, there is marked neutrophilic exocytosis, and numerous keratinocytes lost intercellular connections and undergo lytic necrosis. Superficial and mid dermis show perivascular to diffuse, moderate to severe inflammatory infiltrates composed by viable and degenerated neutrophils, macrophages, and lesser numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Significant lesions were not seen in the hypodermis.Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Morphologic diagnosis: Haired skin; severe, subacute, proliferative, necrotizing, and crusting dermatitis with intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusion bodies. Etiologic diagnosis: Poxviral dermatitis. Etiology: Swine poxvirus.Contributor's Comment:

The clinical case reflects typical clinical signs and lesions of congenital swine poxvirus infection. Swine pox (SwP) is a sporadic disease of pigs caused by swine pox virus (SwPV) belonging to the Poxviridae family. SwP is a skin disease of worldwide distribution, generally associated with poor sanitary status of herds, and can be vectored by pig lice (Haematopinus suis) and domestic flies (Musca domestica).4,8 The disease is pathologically characterized by the formation of pustular/papular skin lesions in different regions of the body, with more severe forms in young pigs (<3-4 months), including neonates with the condition (congenital SwP).6,7SwPV is the only member of the genus Suipoxvirus in the subfamily Chordopoxvirinae. As all poxviruses, it has a DNA genome that replicates in the host cell cytoplasm. SwPV has a linear double-stranded DNA molecule with 150 genes, of which 146 conserved genes encode proteins essential for survival in the host cell.1,7 SwPV replication in infected cells can generate two forms of virions: 1) mature virions (MV), which are the vast majority, and are released by budding or after cell lysis, and 2) extracellular enveloped virions (EEV), which leave the cell by exocytosis.7 The difference between the two forms is the stability in the ambient, being MVs very stable and EEVs relatively fragile.7

The clinical signs associated with SwPV infection are directly related to age and viral load. The most affected animals are relatively young (<3-4 months of age), and the condition has high morbidity at the herd level, although mortality is usually very low.4,7 In contrast, SwPV infection in adult animals is usually mild/subclinical and self-limiting. It has been suggested that congenital infections may result from infected and viremic sows during gestation, causing fetal membrane infection.6 The pathogenesis of congenital SwPV infection in pigs has not been completely elucidated; however, compartmentalization of placental membranes in swine probably explains why some fetuses are affected and others are not.4,6,7

The topography of the skin lesions is commonly found throughout the body but more evident on the flanks, ventral abdomen, legs, inguinal areas, and ears. The incubation period of SwPV infection ranges from 4 to 14 days and the lesions evolve from macules, papules, and vesicles to umbilicated lesions with purulent contents, followed by crusting. Congenitally affected piglets usually have cutaneous lesions at birth, being stillborn or dying within a few days. Lesser affected animals can survive and heal the cutaneous lesions.

The typical histological features of SwPV infection comprises hydropic degeneration of keratinocytes of the epidermal stratum spinosum and follicular epithelium during the papular phase. As a result, thickening of the epidermis due to mild spongiosis can be observed; however, epidermal hyperplasia caused by SwPV is usually less prominent than that caused by the other poxviruses.7 Other finding are eosinophilic inclusion bodies in the cytoplasm of infected cells.7 Regarding inflammation, the damage caused by virus replication on keratinocytes causes recruitment of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes, forming intraepithelial pustules, as well as in the superficial and mid-dermis.4,6,7

The presumptive diagnosis of SwP is based on the observation of typical macroscopic skin lesions and the presence of epidermal hyperplasia with ballooning degeneration of keratinocyes and inclusion bodies on histopathology. Differential diagnoses of SwPV infection are infectious diseases such as vesicular diseases (foot-and-mouth disease, vesicular exanthema of swine, vesicular stomatitis, swine vesicular disease and Seneca virus A infection), early stages of ringworm, localized streptococcal and staphylococcal epidermitis, and non-infectious diseases such as pityriasis rosea, allergic skin lesions, and sunburn.6,7

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Pathology Department Veterinary Faculty, Autonomous University of Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain. https://www.uab.cat/web/els-serveis/-servei-diagnostic-de-patologia[1]veterinaria1297063220061.htmlJPC Diagnoses:

Haired skin: Dermatitis, necrotizing and proliferative, subacute, multifocal, severe, with ballooning degeneration and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions.

JPC Comment:

This was a truly phenomenal case of congenital swinepox, complete with clear viral inclusions and all the classic histologic features of the disease. The JPC extends sincere gratitude to the contributor of this case for providing such an exceptional example of this entity for the Wednesday Slide Conference!One of the very first questions posed to conference participants was, “If poxvirus is a dsDNA virus, why are the inclusions cytoplasmic instead of intranuclear?” This is because poxviruses are unique among DNA viruses in that they possess all their own required machinery, including their own DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, to carry out replication and transcription independent of the host cell nucleus.9 Poxviruses can even go so far as to form their own membrane-bound "mini-nuclei" within the cytoplasm, derived from rough endoplasmic reticulum.9 These cytoplasmic sites contain all the components needed for viral DNA replication and protein synthesis. As such, poxviral inclusions will be seen in the cytoplasm of infected keratinocytes instead of in the nucleus.

The contributor lists some great differentials to consider for swinepox in pigs where the condition is not thought to be congenital. For congenital cutaneous conditions, however, only swinepox virus and parvovirus are reported to cause lesions in neonatal pigs.6 In conference, it was also mentioned that vaccinia virus, another poxvirus that was previously used for smallpox vaccination in humans, was once considered a cause of poxviral dermatitis in pigs due to its broader species tropism, but this is no longer seen due to the cessation of the use of vaccinia virus for smallpox vaccines. Congenital swinepox is thought to occur via intrauterine infection resulting in a low-level viremia within the sow that allows the virus to spread to the fetal membranes. 6 Swine placental membranes are compartmentalized, so while some fetuses are affected, others may not be. 6

The pathogenesis of poxviruses involves the inhibition of a cytosolic pathogen recognition receptor (PRR) known as protein kinase R (PKR), which is a crucial part of the host immune system that limits viral replication in an infected cell via phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α).3 PKR recognizes double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) produced during viral replication and helps control major signaling pathways involved in the immune response, such as the integrated stress response (ISR), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and the NF-κB pathway.2 During the poxviral replication process, long dsRNAs are generated as intermediates for translation of the viral genome. When a dsRNA fragment is longer than 33 base pairs (bp), two PKR molecules bind to the RNA and become dimerized, followed by autophosphorylation to become an active kinase.2 Once activated, PKR can then either undergo nuclear translocation to act on the above-listed transcription factors or it can phosphorylate cytoplasmic eIF2α, which is a competitive inhibitor of eIF2B, the factor that recycles eIF2 for subsequent rounds of translation.2,5 This inhibition globally halts new protein synthesis for both host and viral mRNA.5 Poxviruses produce a pair of proteins, known as E3 and K3, that antagonize PKR and enable viral activity within cells.3 Protein E3 binds dsDNA and inhibits PKR activation, while protein K3 acts as an eIF2α analog for PKR, limiting activation of eIF2α by making less PKR available for eIF2α binding.3

Conference discussion concluded with a review of other significant poxviruses in veterinary species, of which the most notable were cowpox, due to its wider species tropism and penchant to use rodents as reservoir hosts, monkeypox, due to its current relevance in the U.S., and Ectromelia virus in mice, also known as mousepox. To wrap everything up with a bow, participants reviewed what poxviral virions look like on electron microscopy, which Dr. Bradley, promptly tossing the stereotypical dumbbell reference out the window, affectionally refers to as “tater tots” or “squished tater tots.” Conference participants unanimously agreed that “tater tots” needs to catch on pronto.

References:

- Afonso CL, Delhon G, Tulman E R, Lu Z, Zsak A, Becerra VM, Zsak L, Kutish GF, & Rock DL. Genome of deerpox virus. Journal of Virology. 2005;79(2):966–977.

- Chung J, Lee Y, Yoon J, Kim Y. Deciphering the multifaceted role of double-stranded RNA sensor protein kinase R: pathophysiological function beyond the antiviral response. RNA Biol. 2025;22(1):1-14.

- Haller SL, Park C, Bruneau RC, Megawati D, Zhang C, Vipat S, Peng C, Senkevich TG, Brennan G, Tazi L, Rothenburg S. Host species-specific activity of the poxvirus PKR inhibitors E3 and K3 mediate host range function. J Virol. 2024;98(11):e0133124.

- Mech P, Bora DP, Neher S, Barman NN, Borah P, Tamuly S, Dutta LJ, & Das SK. Identification of swinepox virus from natural outbreaks in pig population of Assam. Virus disease. 2018;29(3):395–399.

- Taylor SS, Haste NM, Ghosh G. PKR and eIF2alpha: integration of kinase dimerization, activation, and substrate docking. Cell. 2005;122(6):823-5.

- Thibault S, Drolet R, Alain R, et al. Congenital swine pox: a sporadic skin disorder in nursing piglets. Swine Health and Production. 1998;6(6):276–278.

- Freitas TRP. Swinepox Virus. In Diseases of Swine, 11th edition. Edited by JJ Zimmerman, LA Karriker, A Ramirez, KJ Schwartz, GW Stevenson, and J Zhang. 2019; 709-714.

- Kagira, JM, Kanyari PN, Maingi N, Githigia SM, Ng'ang'a C, & Gachohi J. Relationship between the Prevalence of Ectoparasites and Associated Risk Factors in Free-Range Pigs in Kenya. ISRN Veterinary Science. 2013:650890.

- Schramm B, Locker JK. Cytoplasmic organization of POXvirus DNA replication. Traffic. 2005;6(10):839-46.