Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 7

October 18th, 2017

CASE II: 17-14227 (JPC 4102437).

Signalment: 11-year-old female spayed Siberian husky, Canis familiaris, canine.

History: Two months prior to surgery, the patient presented to its primary veterinarian for labored breathing after an altercation with another dog. Radiographs at that visit revealed a thoracic mass cranioventral to the heart. The patient was referred to the cardiology service for an echocardiogram which showed mild pericardial effusion and confirmed the presence of an extra-pericardial, thin-walled, fluid-filled structure cranial to the heart with no associated blood flow. A thoracic CT scan found a 5.9 cm x 4.9 cm x 4.2 cm oval, well-defined, thin-walled soft tissue attenuating mass in the cranial mediastinum with a tubular structure that communicated with the pericardial lumen. Cytology of the fluid within the mass revealed malignant cohesive cells suggestive of carcinoma, but mesothelioma could not be ruled out. The patient presented two months later for tachypnea at which visit moderate pericardial fluid with cardiac tamponade as well as mild pleural effusion was found on cardiac ultrasound. Clinical improvement was short lived (< 5 days) after pericardiocentesis. At that time, a subtotal pericardiectomy was elected to remove the cystic mass.

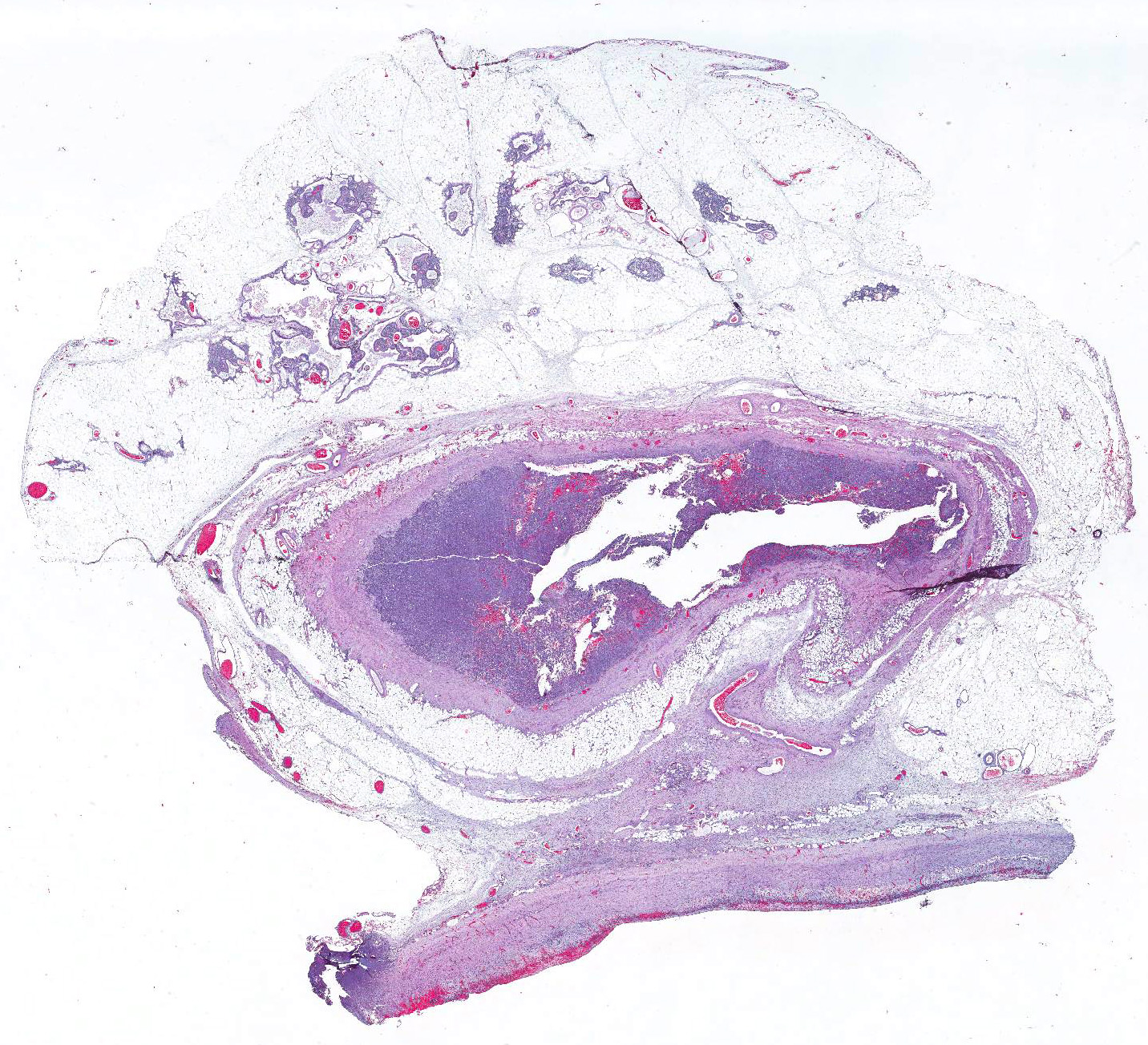

Gross Pathology: Intra-operative findings: The pericardial cystic mass was connected to the pericardium by a 1.5cm orifice at its craniodorsal aspect. On sectioning of the mass, multifocal nodules with an irregular, granular surface extend from the wall of the cystic mass. The affected and adjacent pericardium was mildly thickened.

Laboratory results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.): Cytology of fluid from the cystic mass was consistent with carcinoma with evidence of hemorrhage; cytomorphologic features suggest carcinoma (adenocarcinoma) or possible mesothelioma.

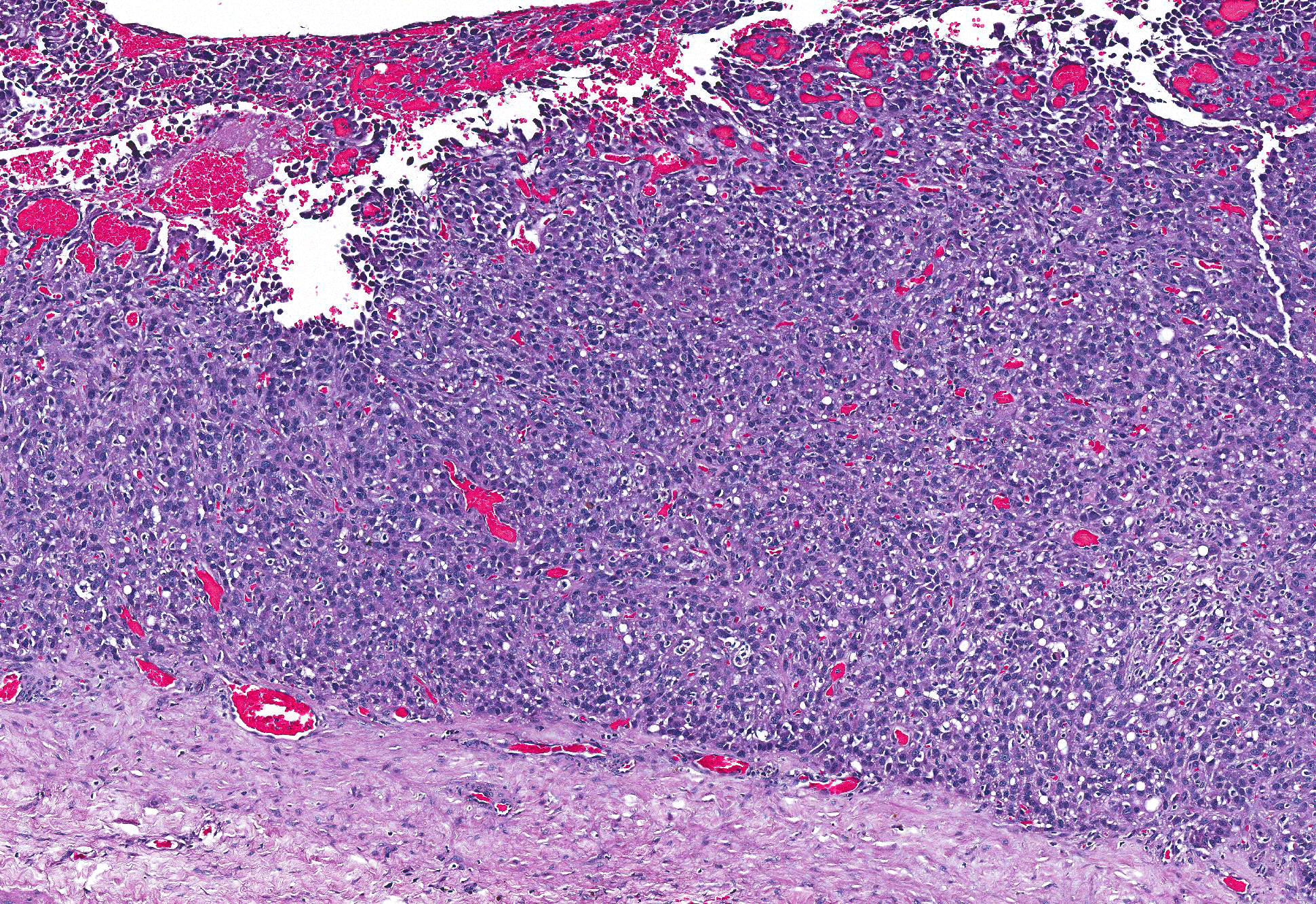

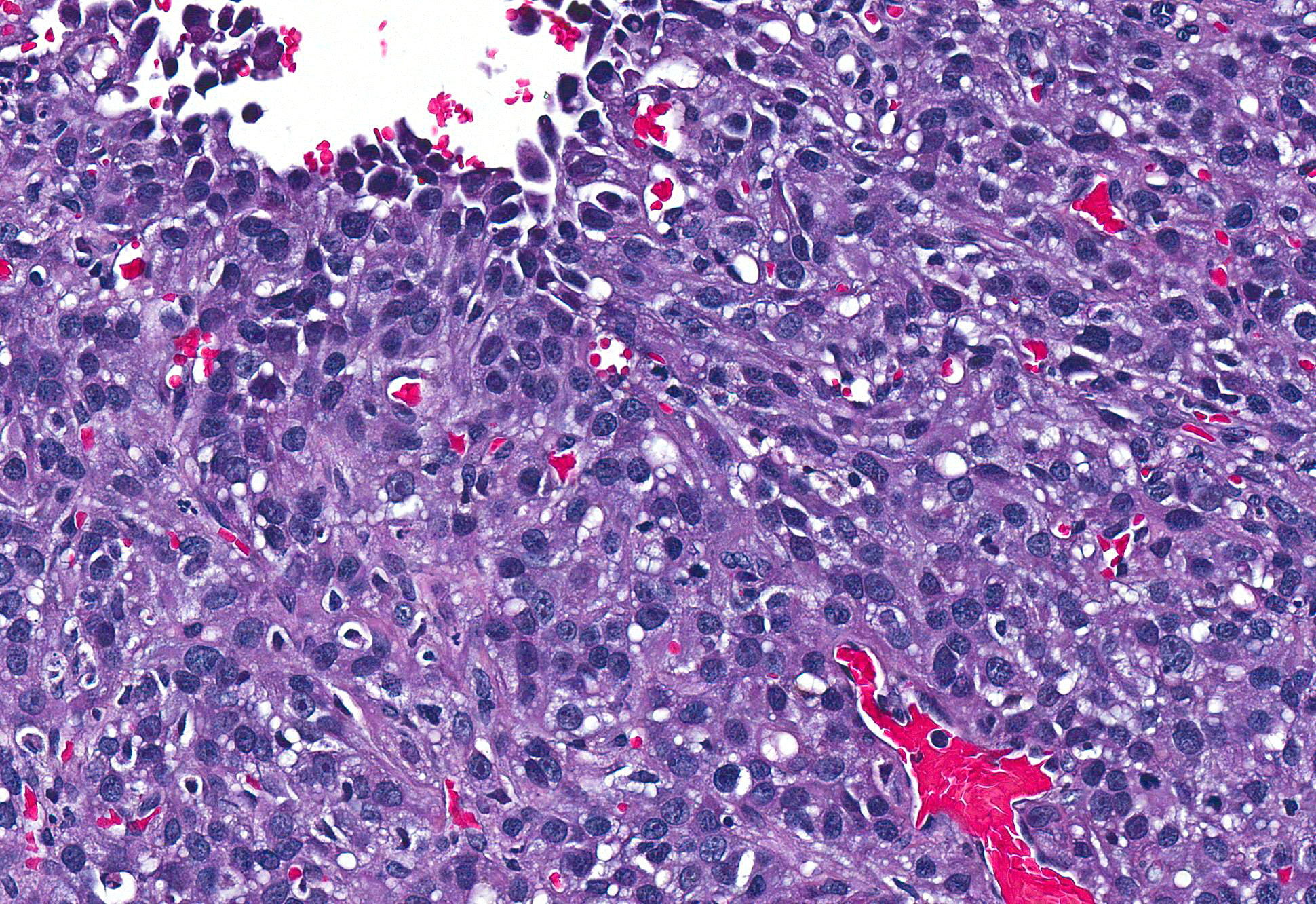

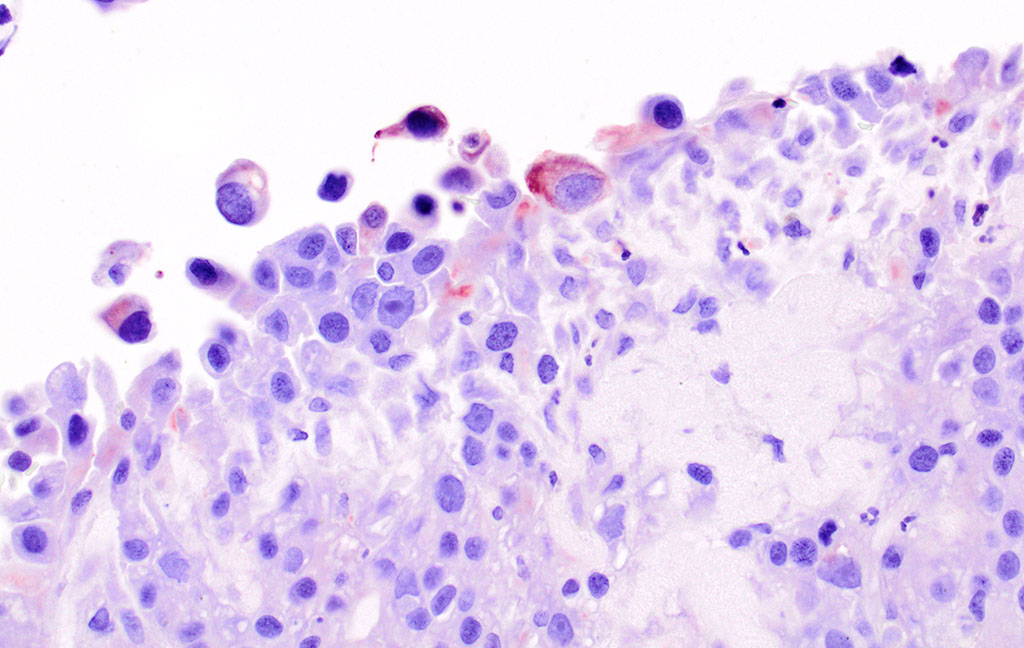

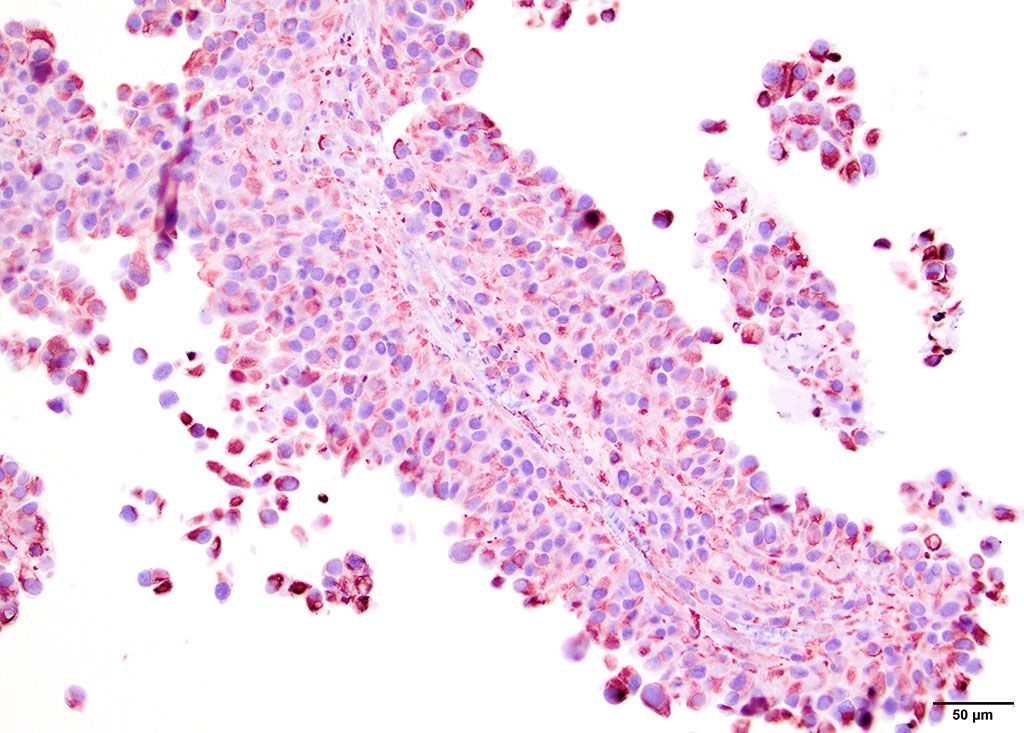

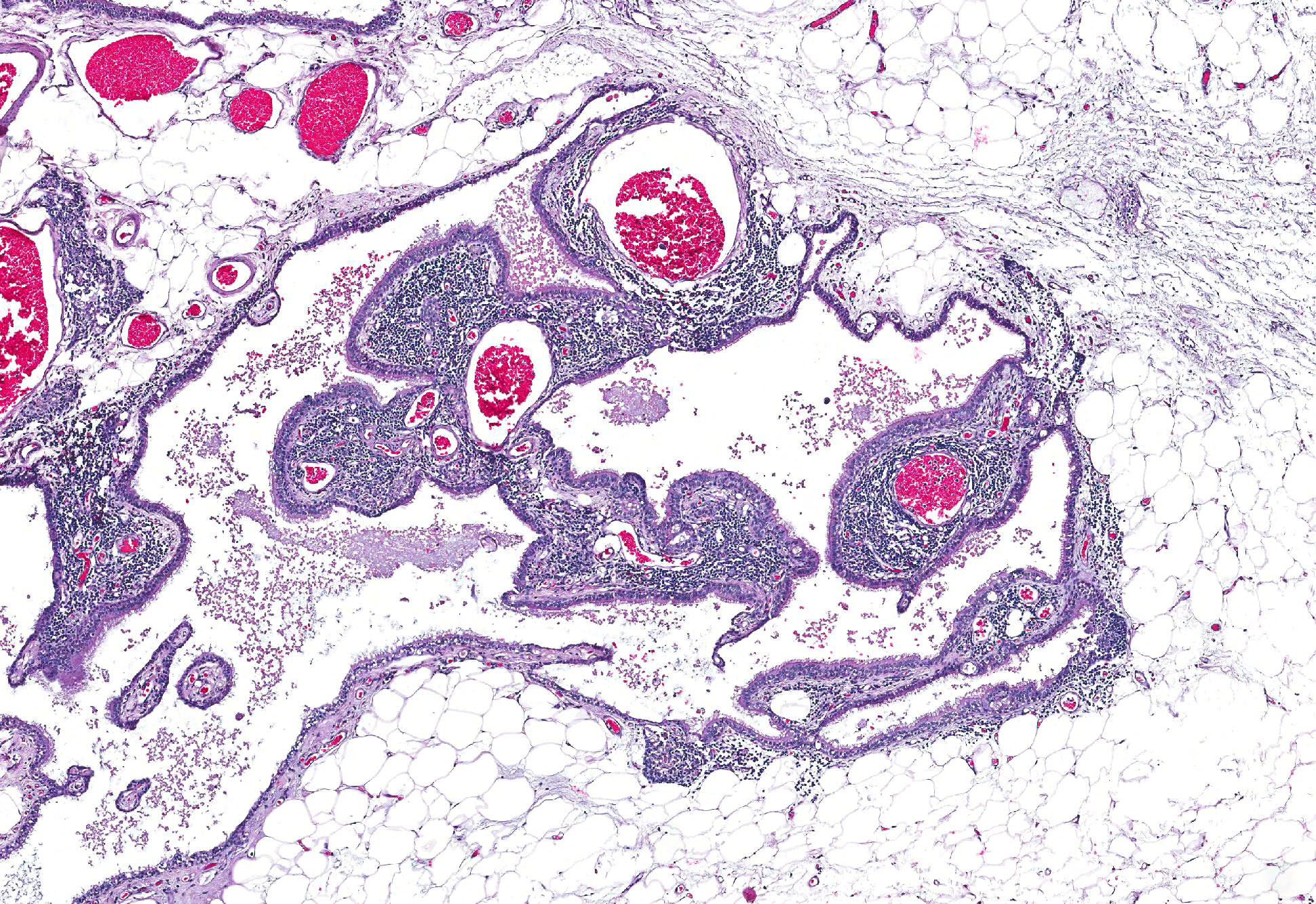

Microscopic Description: Pericardial mass: Focally expanding the pericardial adipose tissue is an encapsulated, well-vascularized mass with a large central cavitation. At the periphery, there are multifocal nodules of densely packed sheets of neoplastic polygonal cells with rare papillary formations supported by a small fibrovascular core. Neoplastic cells exhibit marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis as well as moderate nuclear pleomorphism. Nuclei contain lacy chromatin with distinct, sometimes multiple nucleoli. Cells contain a moderate amount of eosinophilic, variably vacuolated cytoplasm. There are 24 mitotic figures in 10 high power fields with frequent bizarre mitotic figures. Binucleation and karyomegaly are occasionally present. Intra-capsular (not represented on chosen slides) and lymphatic invasion are present. There is multifocal coagulative necrosis and mild hemorrhage. Within the surrounding adipose tissue there are multiple tubular structures lined by simple, ciliated cuboidal epithelium supported by a small amount of fibrous connective tissue which is associated with numerous lymphocytes and plasma cells. The lumens of these tubules contain amorphous, sometimes beaded, eosinophilic material mixed with foamy macrophages and varying number of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The pericardium is markedly expanded by highly cellular collagenous tissue with abundant neovascularization and hemorrhage mixed with mild lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation. Histiocytes often contain course golden-brown pigment (interpreted as hemosiderin).

By immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic cells of the pericardial mass exhibit weak diffuse cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for cytokeratin (wide spectrum, WSS) in approximately 5% of tumor cells (mostly cells located centrally and those that are dissociated). Over 80% of cells have moderate to intense diffuse cytoplasmic vimentin staining (staining is most intense centrally within the mass).

Contributors Morphologic Diagnoses:

1. Mesothelioma, solid variant, with capsular and lymphatic invasion

2. Persistent branchial pouch (embryologic remnants)

Contributors Comment: Mesothelioma is a rare neoplasm in domestic animal species, which typically arise from serosa of the pleura, peritoneum or tunica vaginalis, though pericardial mesotheliomas have been documented with relative frequency in the dog7-9,11,14. Based on their immunohistochemical profile, mesotheliomas are believed to arise from proliferating multipotent subserosal progenitor cells which are immunopositive for both vimentin and cytokeratin (AE1/AE3 in this study).12 Their resting counterparts are immunopositive for vimentin but not cytokeratin. Conversely, terminally-differentiated surface mesothelium is immunopositive for cytokeratin but not vimentin.

Several histological subtypes have been categorized: epithelial, spindle and mixed.11 Further classification of the epithelial subtype has been described by Harbison and Godleski in which there are: 1) papillary form supported by abundant fibrous stroma, 2) less organized papillary form with scant stroma and 3) anaplastic form which makes solid sheets.10 Based on these findings, we have subclassified this particular neoplasm as a solid or anaplastic variant. To our knowledge, histologic subtype has not been found to be prognostically significant.

In addition to being both cytokeratin- and vimentin-positive, mesothelial cells stain with Alcian blue due to their production of hyaluronic acid, a mucopolysaccarhide.15 Common ultrastructural features of mesotheliomas include the presence of long microvilli at their surface, desmosomes and tonofilaments.10

Biological behavior of pericardial mesotheliomas is similar to mesotheliomas that arise at other sites in that they spread via transplantation, local extension and regional metastasis, with distant metastases occurring rarely.10 The presence of clusters of atypical mesothelial cells in lymph nodes of patients with pericardial effusion should be interpreted with caution, as embolized mesothelial cells have been found in regional lymph nodes in dogs with non-neoplastic pericardial effusion.15,19 It is purported that the local inflammation results in widening of intercellular stomata within the mesothelium, through which desquamated reactive mesothelial cells can enter the subserosal stroma and subsequently enter regional lymph nodes by way of subserosal lymphatics.19

An underlying cause for the development of mesothelioma in dogs remains to be elucidated. Spontaneous mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis has been well-characterized in male Fisher 344/N rats.4 In humans, inhalation of asbestos and exposure to Simian virus 40 (SV40) have been linked to mesothelioma.6,10 With regard to pericardial mesothelioma in dogs, asbestos might be a potential contributing factor, particularly for those living in urban settings.10 A causal relationship between asbestos and mesothelioma has not been established, however, and many cases of canine mesothelioma do not have any known exposure to asbestos. In addition, there is a case series of golden retrievers who developed pericardial mesotheliomas after protracted histories of idiopathic hemorrhagic pericardial effusion, suggestive of a chronic inflammatory pathogenesis.11

Based on the unusual clinical description of this lesion, another one interpretation might be malignant transformation of a pericardial cyst. Sisson et al. describes intrapericardial cysts as unilocular or multilocular cysts lined by reactive mesothelium supported by a small amount of fibrous stroma.17

Another differential for mediastinal neoplasia is ectopic thyroid carcinoma. Investigation into intrapericardial neoplasia in dogs found a single case of ectopic thyroid carcinoma as well as a single case of mesothelioma.8 Development of a papillary carcinoma from ectopic thyroid tissue within a branchial cyst has been documented in humans.13 Branchial pouches are embryologic structures that develop into various parts of the head and neck, including medullary C-cells of the thyroid gland.1 Medullary and follicular thyroid carcinomas have been found to be both cytokeratin and vimentin positive using immunohistochemistry.4,5,16 Expression of vimentin in carcinomas is believed to facilitate in tumor progression, namely the phenomenon of epithelial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT). Immunohistochemistry for thyroglobulin and calcitonin was not performed on this mass.

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Pericardium: Mesothelioma, Siberian husky (Canis familiaris), canine.

2. Pericardial fat: Branchial cysts, multiple.

Conference Comment: Mesotheliomas have been reported arising from the pleura, pericardium, and peritoneum, as well as the mesothelial lining of the visceral vaginal tunic (an invagination of the peritoneum) of the testis.2, 14, 19 Of the four locations, mesotheliomas of the peritoneum are most common in domestic animals. Affected animals typically present for peritoneal fluid (ascites), which is characterized cytologically by reactive epithelial-like or mesenchymal-like cells. Cytologic distinction between reactive and neoplastic mesothelial cells is notoriously difficult.

As mentioned by the contributor above there are three recognized histologic subtypes of mesothelioma: epithelioid, spindloid (sarcomatous), and mixed. As with cytology, histologic differentiation between reactive mesothelium and neoplasia is difficult and is dependent on four factors: (1) invasion of the underlying tissue, (2) the presence of neoplastic mesothelial cells in draining lymph nodes or distant organs, and (3) multiple masses within a body cavity. In addition, mesothelial neoplasia appears much thicker and irregularly arranged, whereas reactive mesothelium generally appears as a single layer of regularly arranged cells. Cellular morphology is generally not helpful because both reactive and neoplastic mesothelial cells can appear either well-differentiated or anaplastic. While many specific immunohistochemical (IHC) stains, including epithelial membrane antigen, desmin, glucose transporter protein-1, p53, and Ki67 have proven diagnostically unreliable, mesothelial cells are somewhat unique in that they exhibit dual expression of vimentin and cytokeratin. Thus the combination of histologic pattern and IHC features are necessary for diagnosis of mesothelioma.14 Testicular mesotheliomas are quite rare in most domestic species but are described in dogs, bulls, and rats (Fisher 344 strain).3 Once diagnosed, a presumed primary mesothelioma of the testis must be differentiated from a metastatic mesothelioma that started in one of the other primary locations.2

Conference participants discussed the difficult tissue identification in this case, but most noted that the presence of branchial pouch cysts was beneficial. Branchial pouch cysts are congenital and though rare, are usually found in brachycephalic dog breeds. These cysts are often found in the cranial mediastinum (as in this case), close to thymic tissues, and are lined by a single layer of cuboidal epithelial cells.7

Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Oregon State University

College of Veterinary Medicine

http://vetmed.oregonstate.edu/diagnostic

References:

1. Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: A pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:6976.

2. Agnew DW, MacLachlan NJ. Tumors of the genital systems. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:713.

3. Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH. Rat. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rabbits and Rodents. 4th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016:169.

4. Blackshear PE, Pandiri AR, Ton TT, Clayton NP, Shockley KR, Peddada SD, Gerrish KE, Sills RC, Hoenerhoff MJ. Spontaneous mesotheliomas in F344/N rats are characterized by dysregulation of cellular growth and immune function pathways. Toxicol Pathol. 2014;42(5): 863-876.

5. Calangiu MC, Simionescu CE, Stepan AE, Cernea D, Zavoi RE, Margaritescu C. The expression of CK19, vimentin and E-cadherin in differentiated thyroid carcinomas. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55(3): 919-925.

6. Carbone M, Pass HI, Miele L, Bocchetta M. New developments about the association of SV40 with human mesothelioma. Oncogene. 2003;22: 5173-5180.

7. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:502.

8. Fathi A. The role of immunohistochemical markers in diagnosis and prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Egypt J Path. 2013;33: 1317.

9. Girard C, Helie P, Odin M. Intrapericardial neoplasia in dogs. J Vet Diag Invest. 1999;11: 73-78.

10. Harbison ML, Godleski JJ. Malignant mesothelioma in urban dogs. Vet Pathol. 1983; 20: 531-540.

11. Machida N, Tanaka R, Takemura N, Fujii Y, Ueno A, Mitsumori K. Development of pericardial mesothelioma in golden retrievers with a long-term history of idiopathic haemorrhagic pericardial effusion. J Comp Path. 2004;131: 166-175.

12. McDonough SP, MacLachlan NJ, Tobias AH. Canine pericardial mesotheliomas. Vet Pathol. 1992;29: 256-260.

13. Mehmood RK, Basha SI, Ghareeb E. A case of papillary carcinoma arising in ectopic thyroid tissue within a branchial cyst with neck node metastasis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2006;85(10): 675-676.

14. Munday JS, Lohr CV, Kiupel M. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:592-595.

15. Peters M, Tenhunfeld J, Stephan I, Hewicker-Trautwein M. Embolized mesothelial cells within mediastinal lymph nodes of three dogs with idiopathic haemorrhagic pericardial effusion. J Comp Path. 2003;128: 107-112.

16. Pineyro P, Vieson MD, Romas-Vara JA, Moon-Larson M, Saunders G. Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings of primary and mestastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma in a young dog. J Vet Sci. 2014;15(3): 449-453.

17. Sisson D, Thomas WP, Reed J, Atkins CE, Gelberg HB. Intrapericardial cysts in the dog. J Vet Int Med. 1993; 7(6): 364-369.

18. Stepien RL, Whitley NT, Dubielzig RR. Idiopathic or mesothelioma-related pericardial effusion: clinical findings and survival in 17 dogs studied retrospectively. J Sm Anim Pract. 2000;41: 342-347.

19. Wilson DW. Tumors of the respiratory tract. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:495.