Signalment:

Gross Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Streptomyces are of the family Streptomycetaceae, within the order Actinomycetales. Other bacteria within this order are Nocardia, Mycobacteria, and Actinomyces. Streptomyces are aerobic (unlike Actinomyces) and non acidfast organisms (unlike Nocardia and Mycobacteria) comprising several hundred species. Most are found in the soil and most produce pigments. Many antibiotics, such as the aminoglycosides, tetracyclines and macrolides, are derived from these species. The bacteria are regarded as pathogenic in humans but rarely pathogenic for animals (11), and are a common laboratory contaminant. The genus, however, is clearly pathogenic, as indicated by various reports in the human (9,10) and veterinary (4,7,8,12) literature. Invasive Streptomyces infections of humans are uncommon and have been reviewed recently.(3)

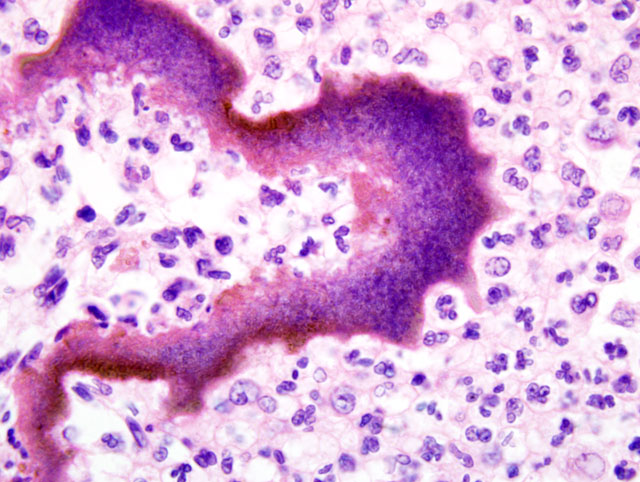

The isolation of this organism on two separate occasions, each time from two different sites plated onto different plates, makes contamination most unlikely. The bacteriology samples collected at necropsy were taken through shaved and ethanol scrubbed skin with sterile instruments to minimize contamination. Additionally, the presence of filamentous bacteria on the histology section clearly demonstrates a genuine intralesional organism. The original source of the infection is not clear in this case, although at this site a perforating and contaminated traumatic injury is a possible inciting cause. These organisms are associated with lesions that are reported to have a low cure rate, often requiring protracted antibiotic treatment.(10) The case reported here indicates that the isolation of Streptomyces from veterinary cases should not necessarily be considered a contamination.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference attendees discussed the differential diagnosis for the presence of colonies of filamentous bacteria, and the contributor provided a very good rubric for refining the differential diagnosis based on atmospheric oxygen requirements and the presence or absence of acid-fast staining. Importantly, most Nocardia sp. only stain acid-fast positive with a modified acid-fast stain (e.g. Fite-Faraco method), which may be useful in differentiating Nocardia sp. from opportunistic Mycobacteria sp., which are strongly positive with routine acid-fast stain.(5) However, not all species of Nocardia are acid-fast positive; in such cases, culture is necessary for differentiation from Actinomyces sp.(5) Other notable members of order Actinomycetales include Dermatophilus congolensis and Streptobacillus moniliformis.(2) Most members of the order are Gram positive; however, Mycobacteria sp. possess a complex cell wall that precludes Gram staining, while Nocardia sp. are only weakly Gram positive.(11)

Compared with Actinomyces sp. and Nocardia sp., Streptomyces sp. and Actinomadura sp. are infrequent causes of disease.(5) Clinically, the lesions caused by these four actinomycetes are indistinguishable, with the classic lesion being an actinomycotic mycetoma.(5) By definition, a mycetoma is a destructive lesion of the skin, subcutis, fascia, and sometimes bone characterized by the triad of tumefaction, draining tracts, and tissue grains (i.e. sulphur granules) of various colors (e.g. white, black, yellow, red, or brown) corresponding to the etiologic agent.(1) Actinomycetic and eumycotic mycetomas are caused by the aforementioned actinomycetes and opportunistic fungi, respectively.(6) Nocardia sp. produces tissue grains less frequently than does Actinomyces sp.(5,6) Scedosporium apiospermum (Pseudoallesheria boydii) and Acremonium hyalinum cause white-grain eumycotic mycetomas, while Curvularia geniculata, Madurella grisea, and Phaecococcus sp. cause black-grain eumycotic mycetomas.(5,6)

Pseudomycetomas are characterized by the same triad of clinical signs as mycetomas, but lack a cement substance unique to true mycetomas.(6) Dermatophytic pseudomycetomas are caused by dermatophytic fungi, most classically in Persian cats.(6) The reader is referred to WSC 2008-2009, Conference 9, Case III for an example of dermatophytic pseudomycetoma. Bacterial pseudomycetoma results when non-branching bacteria (e.g. Staphylococcus sp., Streptococcus sp., Pseudomonas sp., or Proteus sp.) cause the Splendore-Hoeppli reaction in tissue, resulting in nodules composed of pyogranulomatous inflammation with or without fistulous tracts.(6)

References:

2. Biberstein EL, Hirsh DC: Filamentous bacteria: Actinomyces, Nocardia, Dermatophilus, and Streptobacillus. In: Veterinary Microbiology, eds. Hirsh DC, MacLachlan NJ, Walker RL, 2nd ed., pp. 215-222. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2004

3. Carey J, Motyl M, Perlman DG: Catheter-related bacteremia due to Streptomyces in a patient receiving holistic infusions. Emer Infect Dis 7(6):1043-1045, 2001

4. Elzein S, Hamid ME, Quintana E, Mahjoub A, Goodfellow M: Streptomyces sp., a cause of fistulous withers in donkeys. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 109(10):442-443, 2002

5. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM: Skin and appendages. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 686-702. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

6. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK: Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis, 2nd ed., pp. 272-309. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA, 2005

7. Lewis GE, Filder JW, Crumrine MH: Mycetoma in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 161(5):500-503, 1972

8. Moore CP, Heller N, Majors LJ, Whtley RD, Burgess EC, Weber J: Prevalence of ocular microorganisms in hospitalized and stabled horses. Am J Vet Res 49(6):773-777, 1989

9. Mossad SB, Tomford JW, Stewart R, Railiff NB, Hall GS: Case report of Streptomyces endocarditis of a prosthetic aortic valve. J Clin Microbiol 33(12):3335-3337, 1995

10. Moss WJ, Sager JA, Dick JD, Ruff A: Streptomyces bikiniensis bacteriemia. Emerg Infect Dis 9(2):273-274, 2003

11. Quinn PS, Carter ME, Markey BK, Carter GR: The Actinomycetes. In: Clinical Veterinary Microbiology,. pp. 44-145. Wolfe Medical Publications Ltd., London, England, 1995

12. Reinke SI, lhrke PJ, Reinke JD, Stannard AA, Jang SS, Gillette DM, Hallock KW: Actinomycotic mycetoma in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 9(4):446-449, 1986