Signalment:

Gross Description:

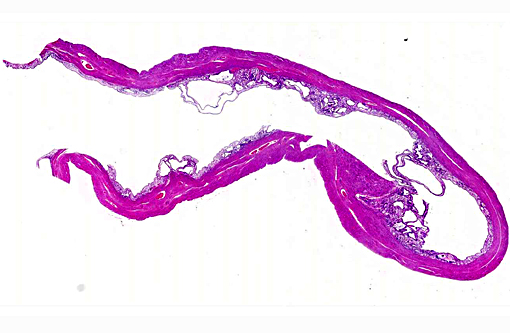

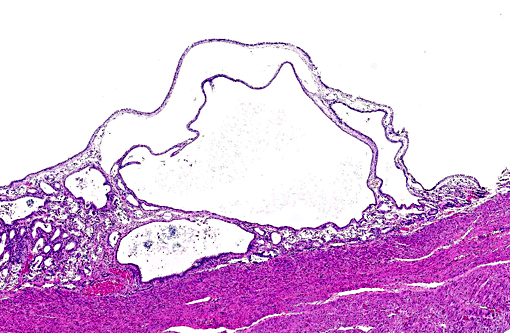

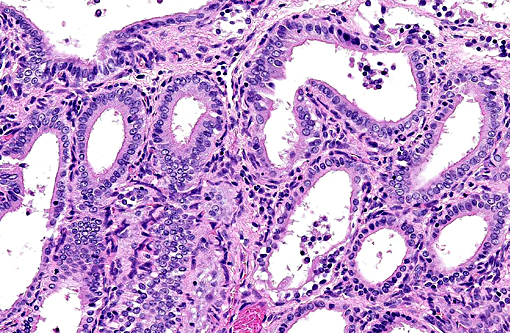

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Some species develop endometrial hyperplasia as a result of excessive and prolonged estrogenic stimulation. Estrogen contributes to the pathogenesis of endometrial hyperplasia by priming the endometrium, via estrogen receptors, to induce the synthesis of intracellular receptors for progesterone.(11) Progesterone, from ovarian corpora lutea (CL), then induces the proliferation and secretion of the endometrium.(6) In addition to the normal estrous cycle, estrogen sources may be endogenous, as with granulosa cell tumors, or exogenous, as with phytoestrogens. (11) Exogenous sources of progesterone can be found in melengestrol acetate (MGA), megestrol acetate, and medroxyprogesterone.(7)

Chronically hyperplastic endometrial glands lead to the gross accumulation of mucoid fluid. Mucometra and hydrometra are considered by some to be variations of the same condition, their difference lying in hydration of the mucin secreted by the endometrium. In addition to the accumulation of fluid concurrent with endometrial hyperplasia, it may also result from the obstruction of a segment of the uterus, cervix, or vagina. If muco/hydrometra persists, the pressure caused by the accumulating fluid results in the attenuation/atrophy of the endometrium and thinning of the uterine wall.(11)

In addition to domesticated animals, cystic endometrial hyperplasia has also been described in raccoons,(3,4) Asian and African elephants,(1) African hunting dogs (Lycaon pictus),(6) a chinchilla,(2) and multiple zoo canid species.(7) With the exception of one primiparous individual, all elephants with CEH (15 total) were nulliparous. Asian elephants had a significantly greater risk of developing CEH while the risk for both Asian and African elephants increased with age.(1) The three African hunting dogs were multiparous; two had CLs and two had ovarian granulosa cell tumors.(6) The chinchilla was nulliparous and had a history of blood being found sporadically in its cage.(2) Zoo canids that had been treated with MGA as a contraceptive were significantly more likely to develop CEH than non-treated canids.(7)

Of the four female raccoons used in the study, three developed endometrial hyperplasia; the uterus of the fourth was not examined. None of these raccoons had received any exogenous hormone therapy nor were any ovarian cysts/tumors or uterine, cervical, or vaginal obstructions identified. Finally, all of the raccoons were nulliparous.(4) The likely pathogenesis of cystic endometrial hyperplasia and resultant mucometra in this case may therefore be similar to that of domestic carnivores (i.e. driven by prolonged and/or repeated estrogen priming followed by progesterone stimulation).

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Uterus: Multiple endometrial cysts.

2. Uterus, muscular tunic: Adenomyosis, multifocal.

Conference Comment:

There are two patterns of cystic endometrial hyperplasia described in the bitch: generalized CEH and pseudoplacentational endometrial hyperplasia (PEH), also referred to as localized endometrial hyperplasia of pseudopregnancy. Both may result in accumulation of secretions within the uterus, but in PEH there will also be cellular debris present from necrosis of the superficial endometrium, which may be confused with pyometra. (9) Additionally, in PEH the proliferation is highly organized and histologically similar to placentation sites seen in pregnancy.(10) In contrast to CEH, noncystic endometrial hyperplasia is generally only recognized microscopically and characterized by irregular proliferation and arrangement of uterine glands. The stroma is generally edematous, the mucosal epithelium hypertrophied, and adenomyosis may be present.(9) Adenomyosis refers to endometrial tissue located within the muscular layers of the uterus. It often appears like normal uterine glands which may be associated with secretory material, or the glandular epithelium may be atrophied leaving only connective tissue and resulting in a cyst like structure in the myometrium.(10)

In the cow CEH is associated with granulosa cell tumors, ovarian follicular cysts a well as exposure to exogenous sources of estrogen.(9, 11) In the mare and camelids it is considered very uncommon and not associated with granulosa cell tumors.(9) CEH has also been observed as a common lesion in miniature pigs, which are often kept as pets and therefore live longer than domestic pigs. In the sow CEH has also been associated with the mycotoxin zearalenone. (5) CEH has also been described in sheep associated with ingestion of estrogen containing plants as well as in goats without association with ingestion of estrogenic plants.(8)

References:

1. Agnew DW, Munson L, Ramsay EC. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia in elephants. Vet Pathol. 2004; 41:179-183.

2. Granson HJ, Carr AP, Parker D, Davies JL. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia and chronic endometritis in a chinchilla. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011; 239: 233-236.

3. Hamir AN, Klein L. Polycystic kidney disease in a raccoon (Procyon lotor). J Wildl Dis. 1996; 32: 674-677.

4. Hamir AN, Kunkle RA, Miller JM, Cutlip RC, Richt JA, Kehrli ME, Jr., Williams ES. Age-related lesions in laboratory-confined raccoons (Procyon lotor) inoculated with the agent of chronic wasting disease of mule deer. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007; 19:680-686.

5. Ilha MRS, Newman SJ, van Amstel S, et al. Uterine lesions in 32 female miniature pet pigs. Vet Pathol. 2010; 47(6):1071-1075.

6. Jankowski G, Adkesson MJ, Langan JN, Haskins S, Landolfi J. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra in three captive African hunting dogs (Lycaon pictus). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2012;43:95-100.

7. Moresco A, Munson L, Gardner IA. Naturally occurring and melengestrol acetate-associated reproductive tract lesions in zoo canids. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:1117-1128.

8. Radi ZA. Endometritis and cystic endometrial hyperplasia in a goat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005; 17:393-395.

9. Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. In: Maxie GM, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:382-383.

10. Schlafer DH, Gifford AT. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, pseudo-placentational endometrial hyperplasia, and other cystic conditions of the canine and feline uterus. Theriogenology. 2008;70(3):349-358.

11. Schlafer DH, Miller RB: Female genital system. In: Maxie GM, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2007:429-564.