WSC 2022-2023

Conference 25

Case I:

Signalment:

A 2-year-old, male, mixed breed dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

This dog was presented to the clinic with one-week history of firm and multicentric swelling of the face and muzzle, acute vision loss, generalized lymphadenomegaly, fever, and asymmetric testicular swelling. The dog was neutered, and the testicles were submitted for histopathology with a presumptive diagnosis of neoplasia. After neutering, the dog was treated with steroids and doxycycline, facial swelling and lymphadenomegaly decreased after treatment. Once therapy was discontinued, facial swelling and lymphadenomegaly waxed and waned for approximately two months. Three months after neutering, the dog developed multiple nodules over the thigh region and stertorous respiration was noticed on physical exam. Skin nodules were submitted for histopathology (slides not included in this WSC submission).

Gross Pathology:

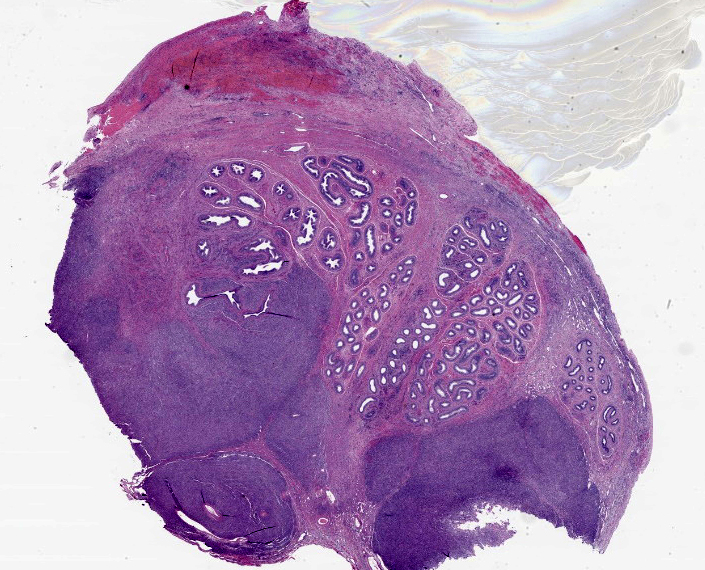

Both testicles (3.5 and 4.5 cm in greatest dimension) were received in 10% buffered formalin for histopathology. Diffusely and bilaterally, the epididymis was markedly enlarged by multiple, expansile, pale tan, firm masses. Similar masses expanded the testicular parenchyma, and elevated and effaced the visceral vaginal tunic. White bar = 1 cm.

Laboratory Results:

Clinical Pathology

Thrombocytopenia (53×103/μl) and leukopenia (1.9×103/μl) were observed. Cytologic examination of FNA material from the submandibular lymph nodes and swollen skin of the muzzle revealed histiocytic inflammation.

Serology

Serum samples were submitted to different laboratories to test for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichiosis, brucellosis, Lyme disease, bartonellosis, and leishmaniasis. All serologic tests came back negative.

Microbiology

Fungal and aerobic bacterial cultures of fresh samples of skin (nodules from thigh region) and popliteal lymph node failed to detect microorganisms.

Microscopic Description:

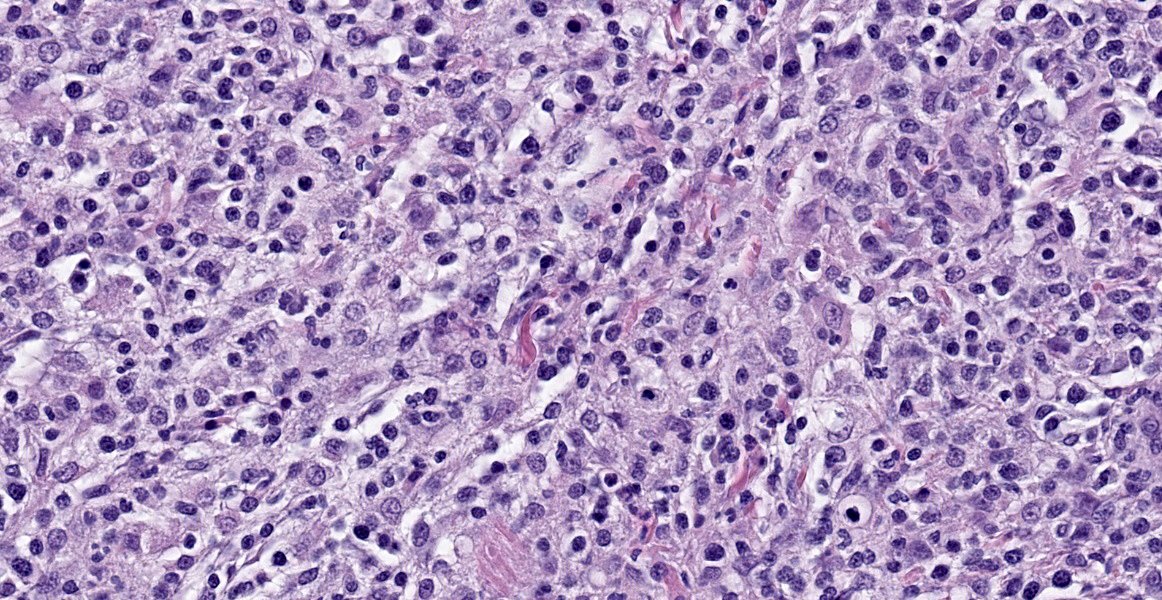

Testicle: Broad, coalescing, areas of angiocentric and interstitial inflammation obliterate the testicular parenchyma and visceral vaginal tunica, and obscure and efface approximately 40% of the epididymal ducts. Inflammatory cells are composed of numerous epithelioid macrophages and lesser numbers of degenerate neutrophils, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Macrophages are often arranged in concentric collections (granulomas) that, in some areas, encompass aggregates of degenerate neutrophils admixed with necrotic cellular debris (pyogranulomas). In addition, multiple macrophages contain a large, 4 to 7 μm, cytoplasmic, clear vacuole. Macrophages often display mitotic figures and cytological atypia, including pleomorphic nucleus and anisokaryosis. There are low numbers of binucleate and multinucleate cells among inflammatory leukocytes. A few areas of lytic necrosis are scattered among inflammatory foci. The lumen of seminiferous tubules and epididymal ducts lacks spermatids and spermatozoa.

The following special stains (not submitted) failed to highlight microorganisms in replicate and appropriately controlled sections: GMS, PAS, Brown & Hopps, Giemsa, Steiner’s, acid fast, and Gimenez.

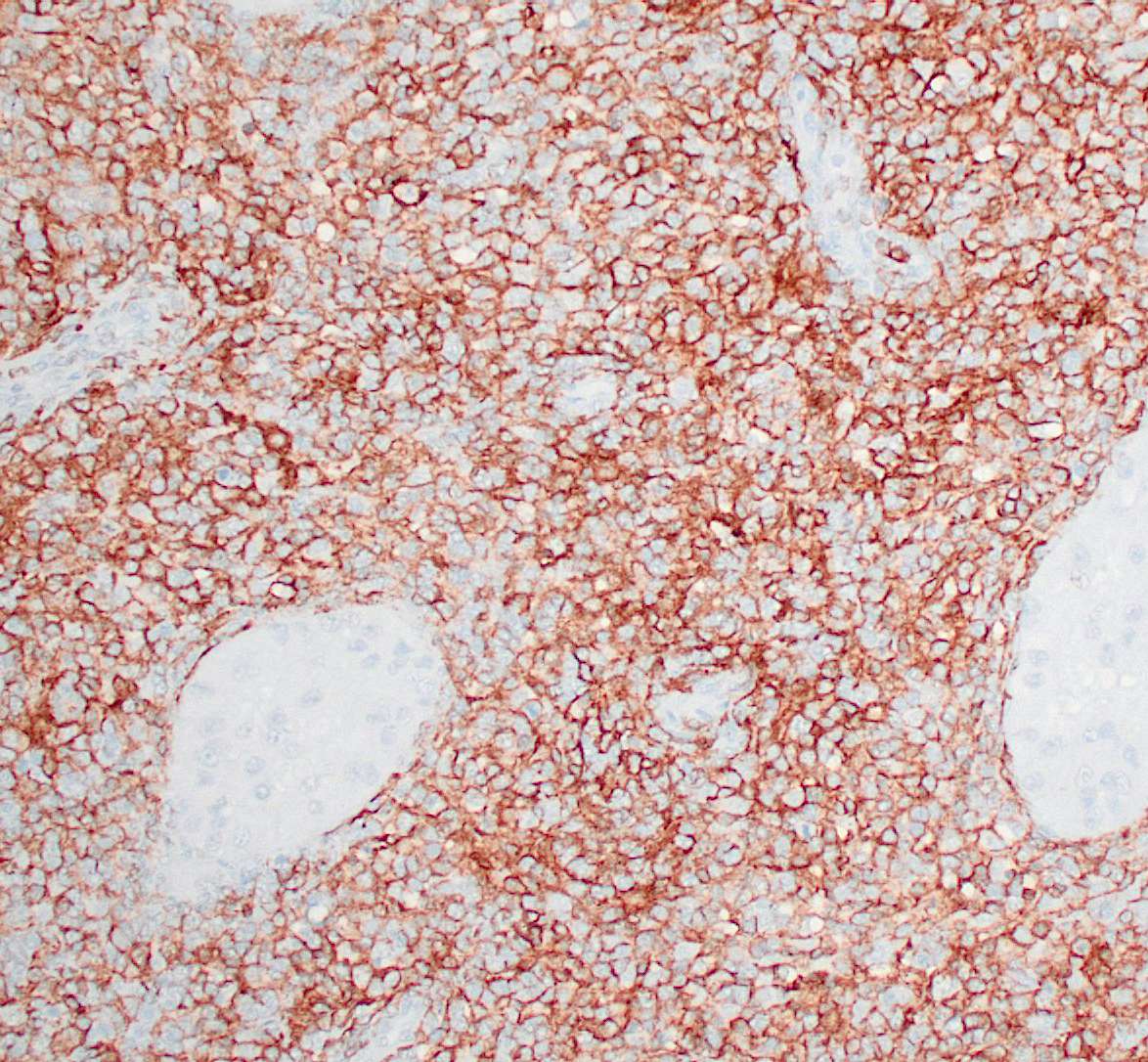

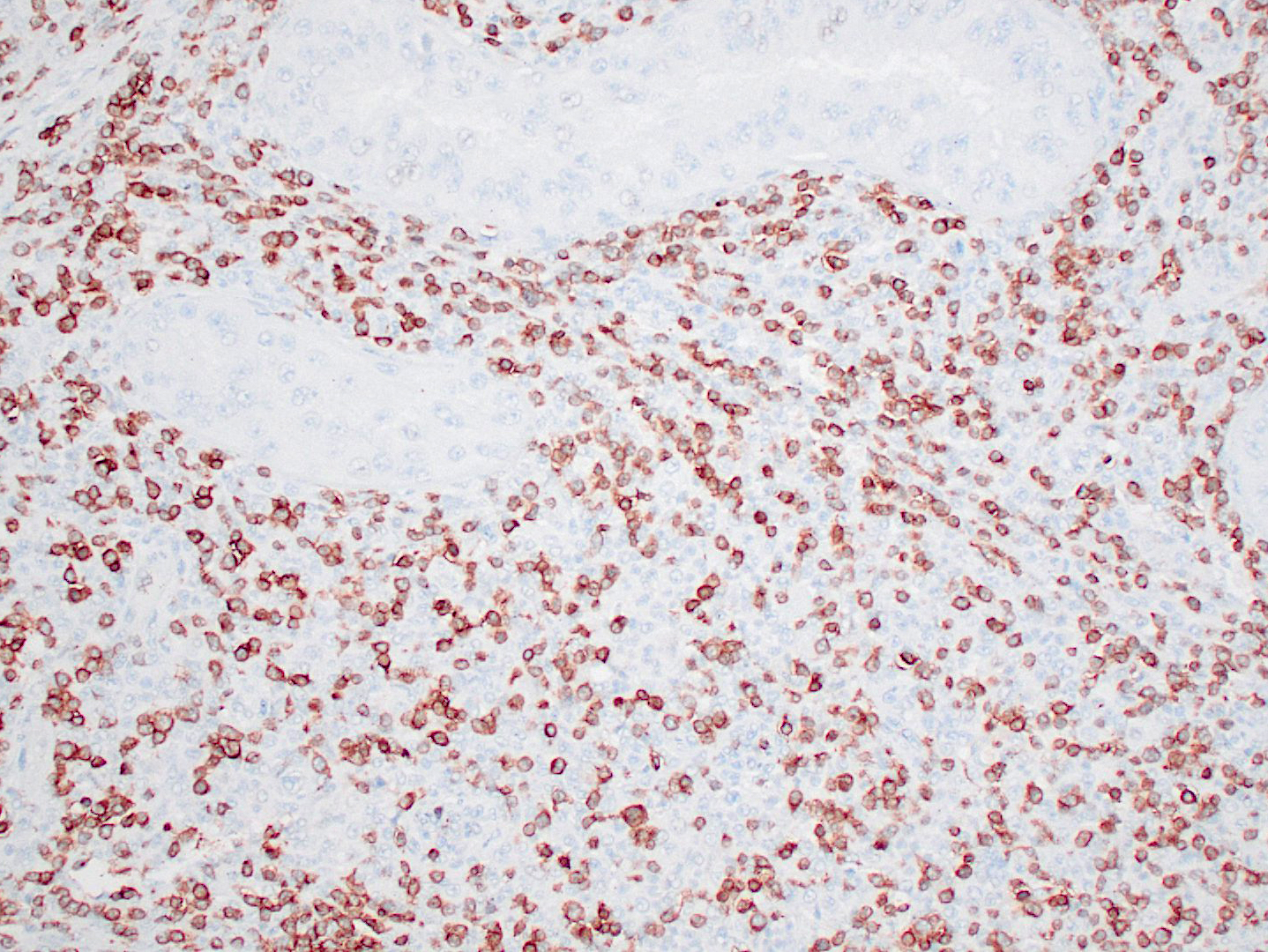

Haired skin (thigh nodules) and popliteal lymph node (not submitted): The dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and lymph node parenchyma were effaced by coalescing areas of inflammation with similar microscopic features as those described above in the testicles. Immunohistochemical staining for CD1a, CD4, and CD11c of frozen skin sections (thigh nodules) was performed. Dermal infiltrates of round cells were positive for CD11c and CD4. The immunoreactivity for CD1a was reported as ambiguous.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Testicle: Epididymitis and orchitis, angiocentric and interstitial, granulomatous, pyogranulomatous, and lymphoplasmacytic, severe, multifocal with histiocytic atypia and testicular atrophy

Haired skin (thigh nodule, not submitted): Dermatitis and panniculitis, angiocentric to interstitial, granulomatous, pyogranulomatous, and lymphoplasmacytic, moderate to severe, diffuse with histiocytic atypia

Popliteal lymph node (not submitted): Lymphadenitis, pyogranulomatous, severe, diffuse with histiocytic atypia

Contributor’s Comment:

The dog in the present case had granulomatous and pyogranulomatous inflammation with histiocytic atypia in the skin, draining lymph nodes, and testes. Based on the immunohistochemical results from skin nodules and negative results from ancillary tests, the final diagnosis was systemic reactive histiocytosis. The initial presentation of this case was strongly suggestive of infectious disease and infection by either Leishmania sp or Brucella sp was suspected. Multiple infectious diseases were ruled out with a combination of special stains, bacteriology, and serology. No immunohistochemistry for dendritic cell markers was done on sections of testis (i.e., they were received in formalin), but immunohistochemistry of frozen haired skin samples was considered sufficient for the diagnosis of systemic reactive histiocytosis.

Reactive histiocytosis is a proliferative disorder of interstitial dendritic cells that has been well characterized in dogs,3 and is uncommonly reported in other veterinary species.1 In dogs, reactive histiocytosis has two clinical manifestations: cutaneous and systemic. While cutaneous reactive histiocytosis is confined to skin and draining lymph nodes, systemic reactive histiocytosis involves extracutaneous sites such as nasal and ocular mucosa, and internal organs. Involvement of the testicles, however, is less common than other extracutaneous sites. In the present case, intraocular and pulmonary involvement was suspected due to acute vision loss and stertorous respiration.4 Systemic reactive histiocytosis was first described in the Bernese Mountain dog, but has now been reported in multiple dog breeds. The diagnosis of reactive histiocytosis is based on immunohistochemistry for dendritic cell markers. Histiocytes in both cutaneous and systemic reactive histiocytoses express markers of dendritic cells (CD1a, CD11c/CD18, CD90, and MHC class II) and a marker of dendritic cell activation (CD4).3 In addition, macrophages lack expression of E-cadherin. It is important to bear in mind that most of these markers are assessable in frozen tissue sections only (CD90, MHC class II, and E-cadherin are the exceptions).

After the diagnosis of systemic reactive histiocytosis was made, the dog of the present case has been on an anti-inflammatory dose of steroids and, according to the practitioner, the dog has shown great improvement.

Contributing Institution:

Wyoming State Diagnostic Laboratory

JPC Diagnosis:

Epididymis: Epididymitis, lymphohistiocytic, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate.

JPC Comment:

This case illustrates the challenge of diagnosing proliferative histiocytic diseases in dogs, which often require immunohistochemical staining for a definitive diagnosis.

Proliferative histiocytic diseases in dogs are typically of dendritic cell origin.5 Dendritic cells arise from CD34+ precursors in the bone marrow and differentiate into interstitial dendritic cells or epidermal dendritic cells (Langerhans cells). Proliferative diseases of interstitial dendritic cells include cutaneous and systemic reactive histiocytoses and histiocytic sarcoma. The main proliferative diseases of canine Langerhans cells are cutaneous histiocytoma and cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Since these diseases all originate from dendritic cells (excepting the hemophagocytic form of histiocytic sarcoma), they express common dendritic cell markers: CD1a, CD11c, CD18, and MHCII.3,5 Dendritic cells, which are professional antigen presenting cells, use CD1a and MHCII for antigen presentation for T cells. CD11c and CD18 are components of the beta-2 integrin heterodimer CD11c/18, one of the adhesion molecules expressed by leukocytes.3

A few additional immunohistochemical stains can assist in differentiating the diseases under the dendritic cell umbrella. Langerhans cells express E-cadherin, which they use to bind homotypically to the epithelium, so canine cutaneous histiocytoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis are both expected to have E-cadherin immunoreactivity. Canine cutaneous and systemic reactive histiocytosis are diseases of activated interstitial dendritic cells and thus express CD4, a marker for activation. They also express CD90 (Thy-1), which is not expressed by Langerhans cells.3

In this section, the main histologic differentials are histiocytic sarcoma, histiocytic inflammation (i.e from dimorphic fungus), and systemic reactive histiocytosis. The relatively bland cellular population lacks atypia and bizarre nuclei, making histiocytic sarcoma less likely. Differentiating between primary inflammation and reactive histiocytosis is not possible based solely on this H&E section, so conference participants decided to morph lymphohistiocytic epididymitis. The clinical history, CD4 immunoreactivity of cutaneous lesions noted by the contributor, and lack of infectious agents on special stains, microbiologic, and serologic testing, however, are consistent with the diagnosis of systemic reactive histiocytosis.

In the multifocal cutaneous lesions of reactive histiocytosis, another differential to consider is canine cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis, which is histologically similar to a histiocytoma but multifocal in distribution. These can generally be differentiated on H&E sections by their growth patterns: they are “top heavy” lesions, with the base of the tumor smaller than the top and tend to track adnexal structures.2 Reactive histiocytosis lesions are generally bottom-heavy, extend into the subcutis, and are oriented along vasculatures.2

This week’s moderator, Dr. Rachel Neto from Auburn University, explained that even though Langerhans cells live within the epithelium, they are thought to arise from precursors within the dermis, and cellular proliferations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis and cutaneous histiocytoma occur in the superficial dermis. She also explained that Langerhans cells are dependent on epidermal growth factors, and the closer they are to the epidermis, the stronger their expression of E-cadherin.

References:

- Helie P, Kiupel M, Drolet R: Congenital cutaneous histiocytosis in a piglet. Vet Pathol. 2014:51(4):812-815.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd. 2016:728-730.

- Moore PF. A review of histiocytic diseases of dogs and cats. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:167-184.

- Pumphrey SA, Pizzirani S, Pirie CG, Sato AF, Buckley FI: Reactive histiocytosis of the orbit and posterior segment in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol. 2013:16(3):229-233.

- Valli VEO, Kiupel M, Bienzle D. Histiocytic proliferative diseases. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd. 2016:247-250.