WSC 2023-2024, Conference 23, Case 1

Signalment:

1.5 year-old neutered male domestic shorthair cat (Felis catus).

History:

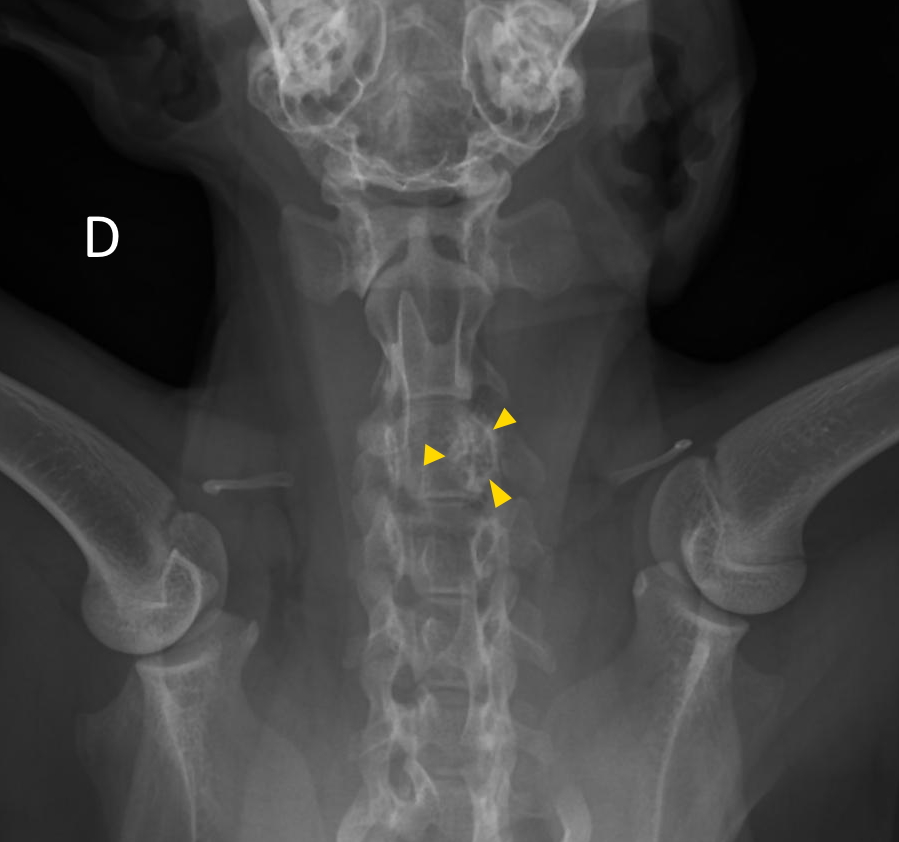

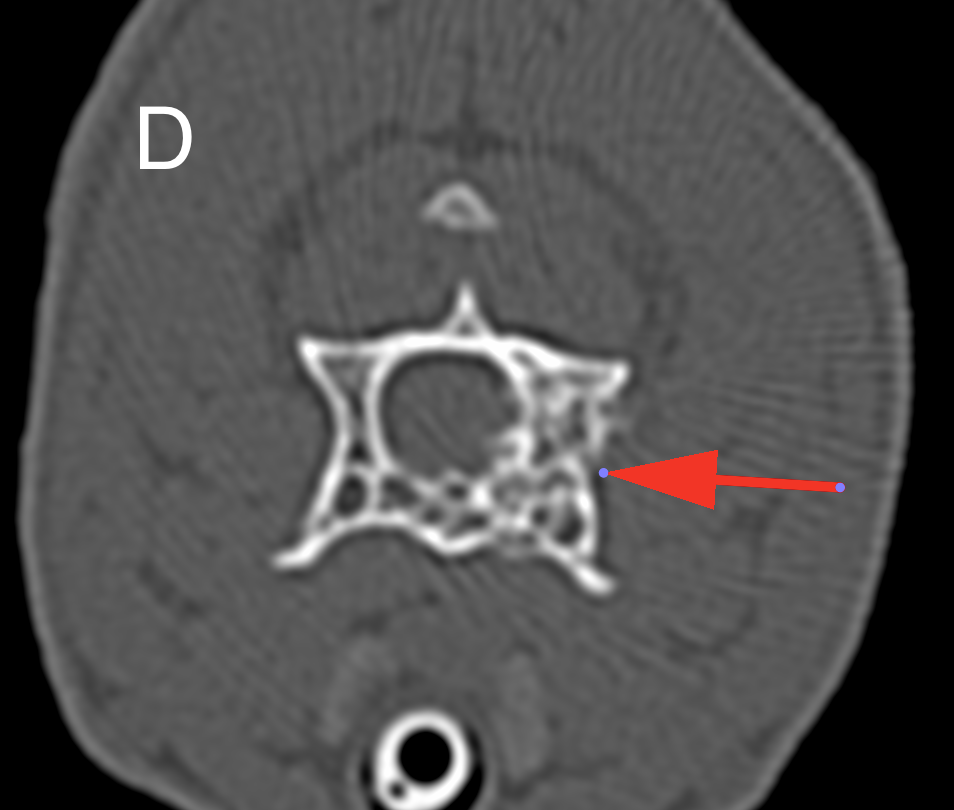

The cat presented for signs of pain evolving over the last month. Palpation during the clinical examination localized the pain to the cervical vertebral spine. Cervical radiographs revealed a moth-eaten lesion involving the left part of C3. A CT scan identified a monostotic osteoproliferative lesion centered on the left pedicle of C3 and causing stenosis of the spinal canal. A benign primitive bone neoplasia was suspected. Decompressive hemilaminectomy was performed one month later. Post-operative CT scan showed residual compressive bone material at the surgical site. The animal’s condition rapidly declined after surgery (stage IV cranial cervical myelopathy). Unfortunately, the cat became comatose and was maintained under artificial ventilation for a few hours before owners elected euthanasia.

Gross Pathology:

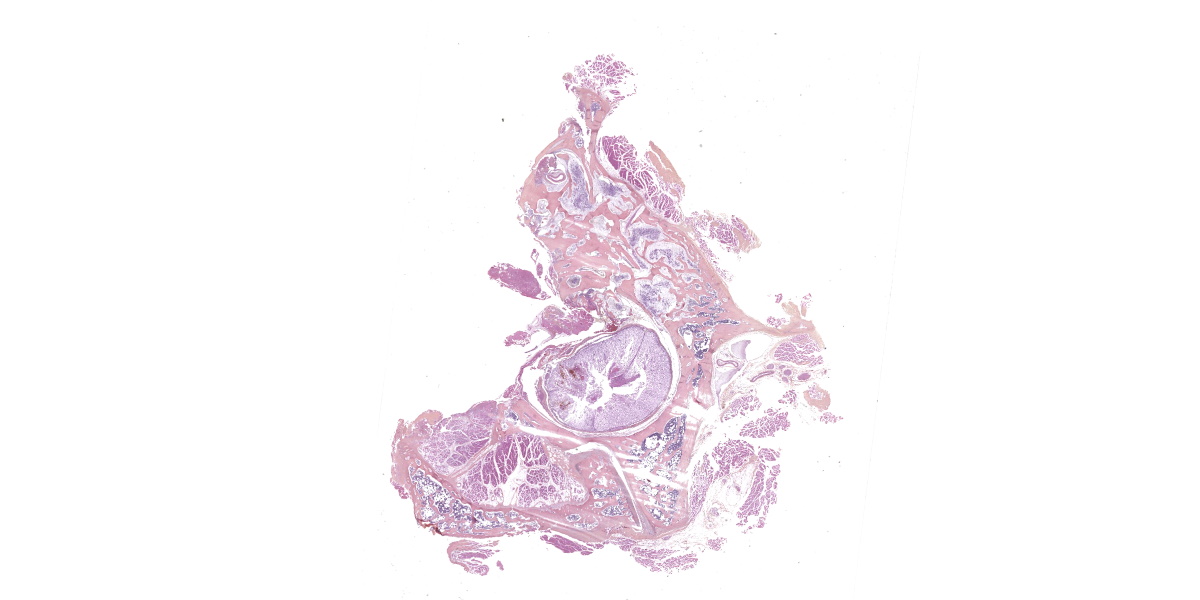

The left lamina of C3 was fractured and an entire fragment of bone was missing due to the hemilaminectomy procedure. The left pedicle of C3 showed a focal and poorly demarcated 1-1.5 cm osteoproliferative lesion with irregularly branching bone trabeculae giving a spongy appearance. The spinal cord was dorsally displaced in the vertebral canal and a central focus of hemorrhagic myelomalacia was identified. The other organs were grossly unremarkable.

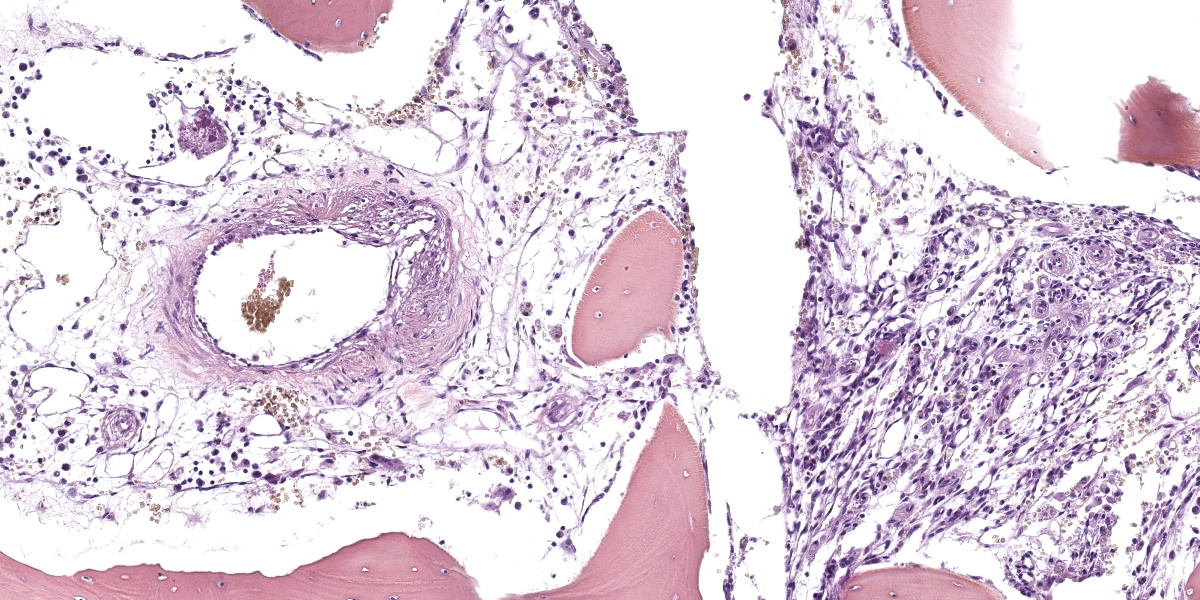

Microscopic Description:

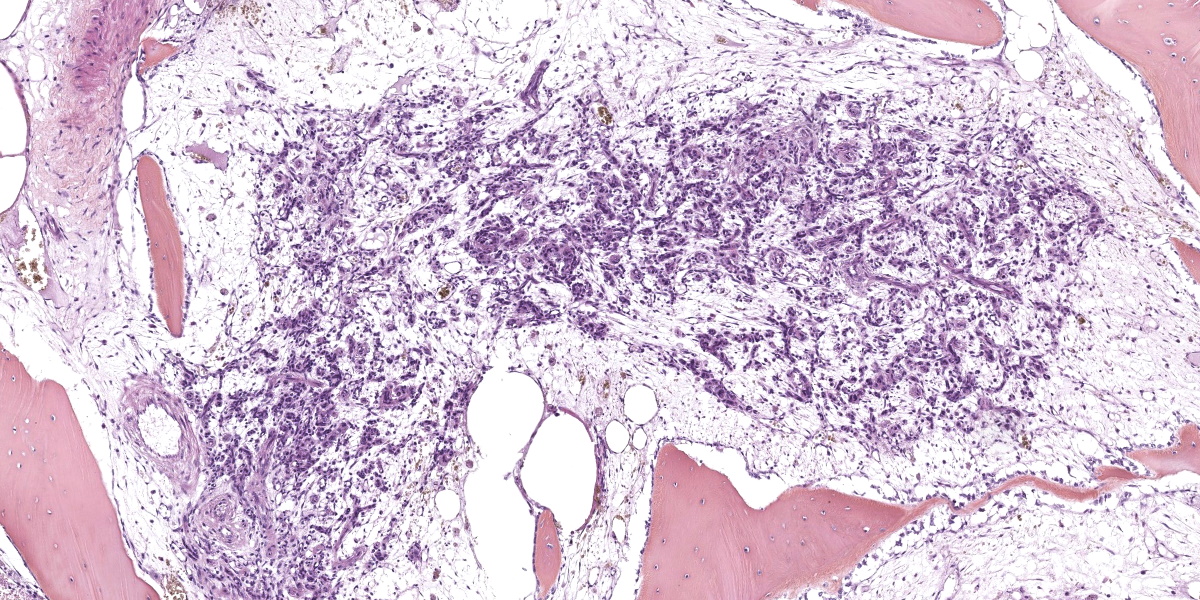

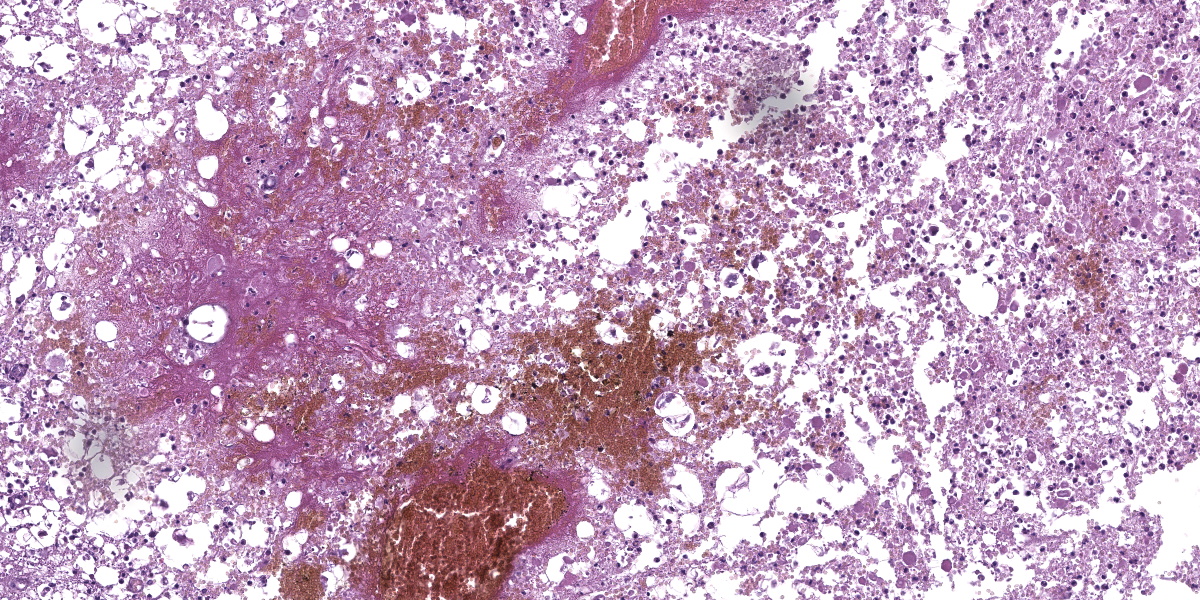

Arising from the left pedicle of the C3 vertebra and protruding into the spinal canal and replacing the bone marrow is proliferative fibrovascular tissue that is poorly demarcated, moderately cellular and infiltrative. The tissue is composed of capillary and arteriole-type vessels, and less often venule-like vessels, that irregular branch and grow within a loose, edematous and myxoid stroma. These vessels are lined by squamous and bland endothelial cells surrounded by pericytes (capillary-like vessels) or by a layer of smooth muscle cells (arteriole-like vessels). Atypias are minimal and no mitoses are observed. Some vessels are associated with small acute hemorrhages, fibrin exudation, or microthrombi. The surrounding trabecular bone shows bone remodeling characterized by irregular and scalloped outlines lined by plump osteoblasts and osteoclastic activity within Howship’s lacunae.

The cervical spinal cord shows a dorso-lateral rotation around its longitudinal axis. Multiple foci of acute hemorrhagic necrosis/myelomalacia are seen within the grey and white matter, most likely secondary to the surgery. Some perivascular cuffs of neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes are identified nearby. Multifocally in the white matter, myelin sheaths are irregularly dilated and sometimes contain vacuolated macrophages indicative of Wallerian-like degeneration. Some axons are also severely dilated and form spheroids. These changes are most likely secondary to the spinal cord compression.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Cervical vertebra C3 (left pedicle): Vertebral angiomatosis (vascular vertebral malformation/hamartoma)

- Cervical spinal cord: Myelomalacia, multifocal, acute, marked, with hemorrhages, axonal degeneration and spheroids.

Contributor’s Comment:

Feline vertebral angiomatosis was first described in 1987 by Wells and Weisbrode in a case series of three cats. In this paper, the lesions were restricted to the thoracic vertebrae and diagnosed as an intraosseous vascular malformation.16

This entity is characterized by a focal proliferation of non-neoplastic blood vessels, hence the more recent denomination of vertebral angiomatosis.4,5,7,10,11,13-16 Similar histological lesions are recognized in human medicine with other names including skeletal angiomatosis, vertebral hemangioma, lymphangiomatosis, and hamartoma.7,16 This condition is not recognized as a true neoplasm because the vascular walls are well differentiated and are composed of multiple cell types, including pericytes, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts.7,10

This condition is rare but is well described in the literature with 12 documented cases.4,5,7,10,11,13-16 Affected cats are typically young and less than 2 years old except for a 3.5 years old cat.4,5,7,10,11,13-16 No sex or breed predisposition have been reported. Animals present with a history, usually over 1 month, of chronic pain, lethargy, reluctance to walk, or progressive paraparesis.4,5,7,10,11,13-16 Most lesions are localized to the thoracic vertebrae but lumbar lesions have been described.4,5,7,10,11,14-16 They tend to originate from the vertebral arch, pedicle, or body and seem to spare the spinous process.7 Occasionally, they can involve multiple vertebrae, but no associated systemic vascular lesion has been observed.5,13 It is considered benign but can be locally aggressive.4,7,10,15 Our case is original because it is the first report to our knowledge of cervical involvement. The clinical signs are likely caused by the spinal cord compression resulting from the expansion of angiomatosis into the spinal canal.

The diagnosis is first approached by imaging, mostly post-myelographic CT scan or MRI, in order to localize the lesion and evaluate the associated spinal cord compression. 4,5,7,10,11,13-16 The differential diagnoses include vertebral new bone formation due to an old trauma, disc extrusion, bone abscess, granuloma, ancient hematoma or migrating foreign body.15 Neoplasia is less likely considering the young age of the affected animals, but lymphoma (especially in FeLV positive cats) or osteosarcoma should be considered.7,15

The therapeutic approach is always surgical with a dual goal: 1) removing the spinal cord compression and 2) making biopsies for histopathological diagnosis.4,5,7,10,11,13-16 Cytologic imprints can be done during the surgery but are of poor diagnostical value.13,15 Adjuvant radiotherapy can be considered because of the potentially locally aggressive nature of the lesion and also because of the difficulty of complete resection in this area.7,11 Outcomes are variable. Some animals receiving surgery with or without radiotherapy are reported as free of disease over the following months or years.5,7,10 However, the surgery is not without risk, and relapse is also reported.4,15

The pathogenesis of feline vertebral angiomatosis is still unclear. Because of the occurrence in young cats and the absence of an associated inflammatory or infectious process, developmental anomaly is currently considered most likely.7,10,11,16

Histopathological features are consistent among all cases and are characterized by a proliferation of rather well-differentiated capillaries, arterioles, and occasionally venules, into a loose and myxoid connective tissue with invasion of the spinal canal and the bone marrow, as well as bone remodeling and new bone formation.4,5,7,10,11,13-16

Other type of angiomatosis have been reported in the cat, affecting the skin,cerebrum, meninges, and lungs.1-3,8,9

Contributing Institution:

Unité d’Histologie et d’Anatomie pathologique

BioPôle Alfort, Département des Sciences Biologiques et Pharmaceutiques

Ecole Nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort (EnvA)

https://www.vet-alfort.fr/

JPC Diagnoses:

1. Vertebra, pedicle and body, hemi-laminectomy site: Angiomatosis, focally extensive, marked, with reactive osteolysis and osteoproliferation (bone modeling).

2. Cervical spinal cord, gray and white matter: Myelomalacia, diffuse, severe, with hemorrhage and axonal degeneration.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent overview of this enigmatic condition that, until recently, had only been reported in young cats. Earlier this year, however, vertebral angiomatosis was reported in a three year old female intact Cavalier King Charles Spaniel who presented for ataxia and paraparesis.6 CT revealed osteolysis of the vertebral body and pedicles of T5 with compressive extradural material within the spinal canal.The dog was treated surgically with a dorsal hemilaminectomy and histopathologic samples collected intraoperatively were consistent with vertebral angiomatosis.6

Vertebral angiomatosis is one member of a cohort of non-neoplastic vascular malformations beset by confusing terminology, overlapping histologic features, and uncertain pathogeneses. Angiomatosis (also known as hemangiomatosis) has two microscopic patterns: either a mixture of blood vessel types, some of which can be cavernous, or a predominance of capillaries. Lobules of mature adipose tissue characteristically accompany the vascular elements.12

In addition to the vertebral angiomatosis so nicely discussed by the contributor, angiomatosis has been identified within the skin and subcutis of cats and dogs and in the skin of cattle. Calves have a reported generalized pattern of angiomatosis in which the heart, lungs, kidneys, and an assortment of other organs are involved.12 There is a single case report of cerebral angiomatosis in a young cat presenting with generalized seizures, the clinical manifestation of bilateral nests of differentiated capillaries within the cerebral gray matter.12

Human and veterinary medicine is rich with various other hamartomatous vascular conditions, including meningoangiomatosis, angioma, and arteriovenous malformations, the parsing of which requires equal measures of stamina and will. An excellent 2021 comparative review of proliferative vascular disorders in the central nervous system is a helpful reference for those attempting to understand the nuances of these difficult diagnoses.12

Our moderator this week was Dr. Julie Engiles, Professor of Pathology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Engiles began discussion of this case with a review of vertebral anatomy and by noting the important structures, such as the vertebral artery, that can be used as orientation landmarks on this challenging slide. Dr. Engiles also stressed the importance of a collaborative approach among pathologists, radiologists, and clinicians in cases like this, where locating and appropriately sampling the lesion would be difficult without the insight provided by other members of the medical team. In this case, the lesions presented radiographically with an aggressive, moth-eaten appearance which provides helpful context for the relatively bland histologic appearance of the proliferative cells.

Immunohistochemically, the vascular markers Factor VIII and ERG helped to visualize the disorganized proliferation of vascular elements, while smooth muscle actin highlighted the smooth muscle in the proliferating vessel walls. Dr. Engiles noted that the proliferation of multiple cell types, including endothelial smooth muscle myocytes, and pericytes, supports the nonneoplastic classification of this entity, as neoplasia is typically characterized by the aberrant proliferation of a single cell type. The moderator noted that this lesion is sometimes called a hamartoma, which seems to connote an indolent, static process at odds with the typically proliferative and infiltrative behavior of these lesions. For this reason, the moderator prefers the more dynamic term angiomatosis.

Conference participants discussed the abundant ancillary changes in section, such as the polyphasic atrophy, degeneration, and regeneration present in the surrounding skeletal muscle. The history of hemilaminectomy at the site complicated analysis of these changes, making it difficult to determine which changes were due to surgical manipulation and which were caused by the pressure of the expansile vertebral angiomatosis.

Participants felt that the bone changes caused by the vertebral angiomatosis were significant and should be mentioned in the morphologic diagnosis. Participants also felt the morphologic diagnosis should acknowledge the hemilaminectomy that is an obvious feature of the section. Both were ultimately included in the morphologic diagnosis for this fascinating entity.

References:

- Baron CP, Puntel FC, Fukushima FB, da Cunha O. Progressive cutaneous angiomatosis in the metatarsal region of a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2020;256(2):226?229.

- Bulman-Felming J, Gibson T, Kruth S. Invasive cutaneous angiomatosis and thrombocytopenia in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;234(3):381?384.

- Corbett M, Kopec B, Kent M, Rissi DR. Encephalic meningioangiomatosis in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022;34(5): 889?893.

- Belluzzi E, Caraty J, Vincken G, Esmens MC, Bongartz A. Vertebral angiomatosis recurrence in a 14?month?old Maine Coon cat. Vet Rec Case Rep. 2018;6(4):11-13.

- Frizzi M, Ottolini N, Spigolon C, Bertolini G. Feline vertebral angiomatosis: two cases. J Feline Med Surg Open Rep. 2017;3(2): 205511691774412.

- Gagliardo T, Pagano TB, Lo Piparo S, et al. Vertebral angiomatosis in a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2024;60(1):36-39.

- Hans E, Dudley R, Watson A, et al. Long-term outcome following surgical and radiation treatment of vertebral angiomatosis in a cat. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253 (12):1604-1609.

- Jenkins T, Jennings R. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a Persian cat. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2017;29(6): 900?903.

- Kipar A, Hetzel U, Armien A, Baumgartner W. Bilateral focal cerebral angiomatosis associated with nervous signs in a cat. Vet Pathol. 2001;38(3):350?353.

- Kloc PA, Scrivani PV, Barr SC, et al. Vertebral angiomatosis in a cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2001;42(1):42?45.

- Leonardi H, Poirier V, Iverson M, Samarani F. Successful long-term outcome with radiation and prednisolone following a postoperative feline vertebral angiomatosis relapse. JFMS Open Rep. 2023;9(1): 205511692311550.

- Marr J, Miranda IC, Millder AD, Summers BA. A review of proliferative vascular disorders of the central nervous system of animals. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(5):864-880.

- Meléndez-Lazo A, Ros C, de la Fuente C, Anor S, Fernandez-Flores F, Pastor F. What is your diagnosis? Vertebral mass in a cat. Vet Clin Pathol. 2017;46(1):185? 186.

- Ricco C, Bouvy B, Gomes E, Cauzinille L. Lumbar vertebral angiomatosis in a cat: a clinical case. Revue Med Vet. 2015;166 (11): 332?335.

- Schur D, Rademacher N, Vasanjee S, McLaughlin L, Gaschen L. Spinal cord compression in a cat due to vertebral angiomatosis. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12(2): 179?182.

- Wells M, Weisbrode S. Vascular Malformations in the Thoracic Vertebrae of Three Cats. Vet Pathol. 1987;24(4): 360?361.