CASE II: A20-12826 (JPC 4166557)

Signalment:

64-week-old female, Shaver White Leghorn, (Gallus gallus domesticus) chicken

History:

Weekly mortality rate increased from 0.42% to 0.50%

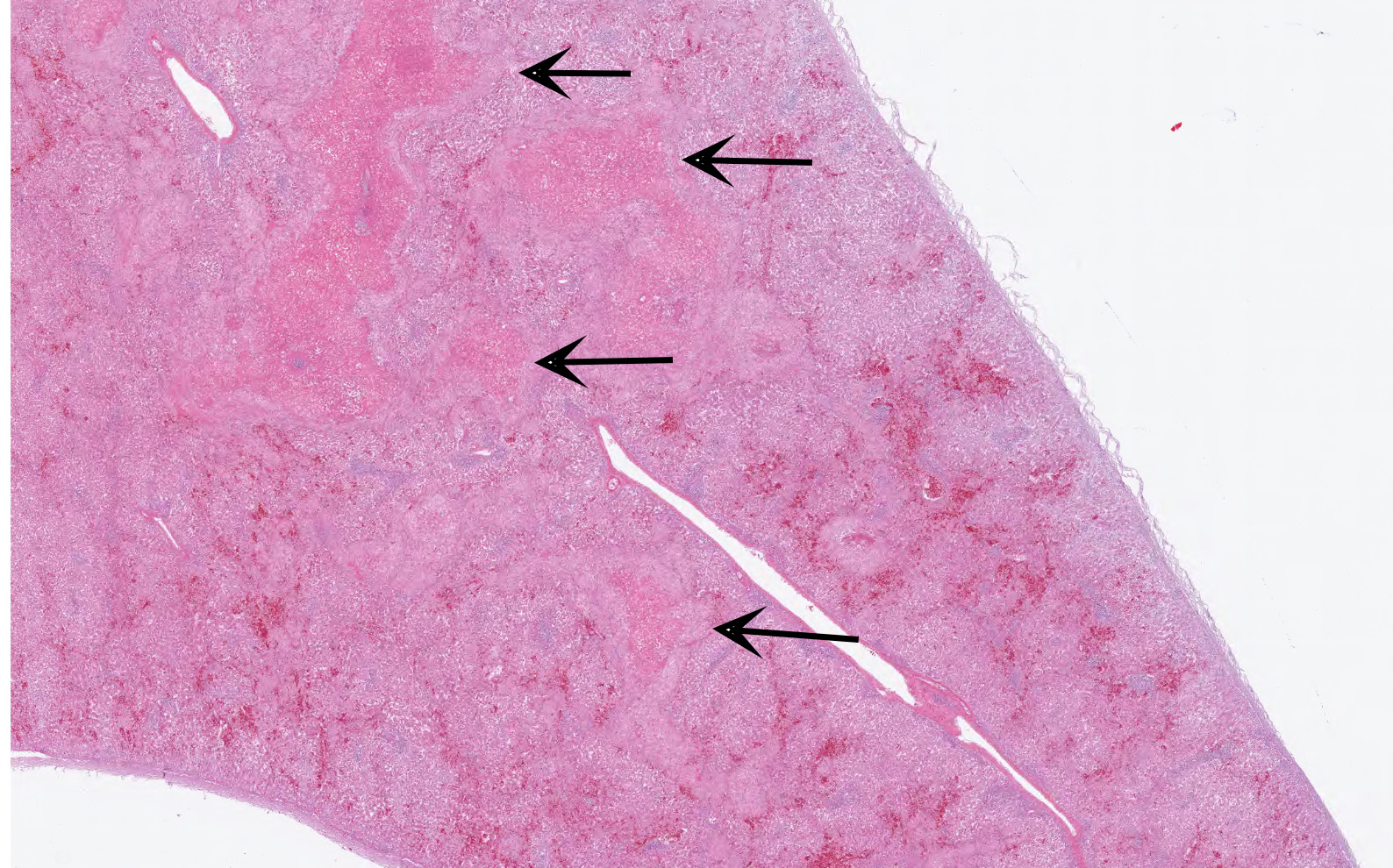

Gross Pathology:

The coelomic cavity contained 50 mL serosanguineous fluid with variably sized blood clots. The liver was enlarged, friable, and mottled pale to dark red with yellow foci. Hepatic fractures were associated with hemorrhage into adjacent parenchyma and subcapsular or capsular blood clots. The spleen was diffusely enlarged and friable.

Laboratory Results:

The liver was positive for avian hepatitis E virus nucleic acid by PCR. No pathogenic bacteria were isolated from culture of liver or spleen. Rare Spirurida spp. were detected in cecal content by fecal flotation.

Microscopic Description:

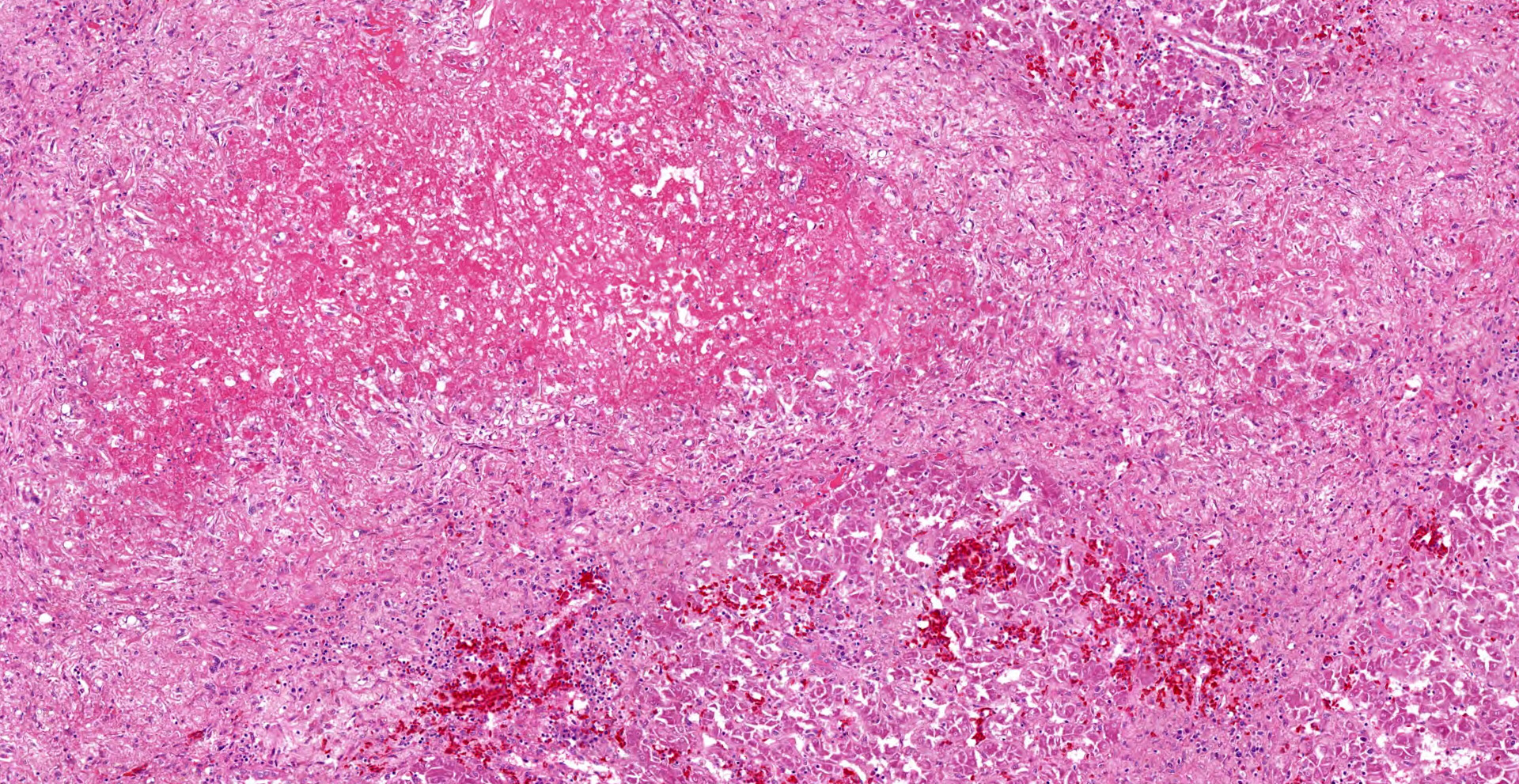

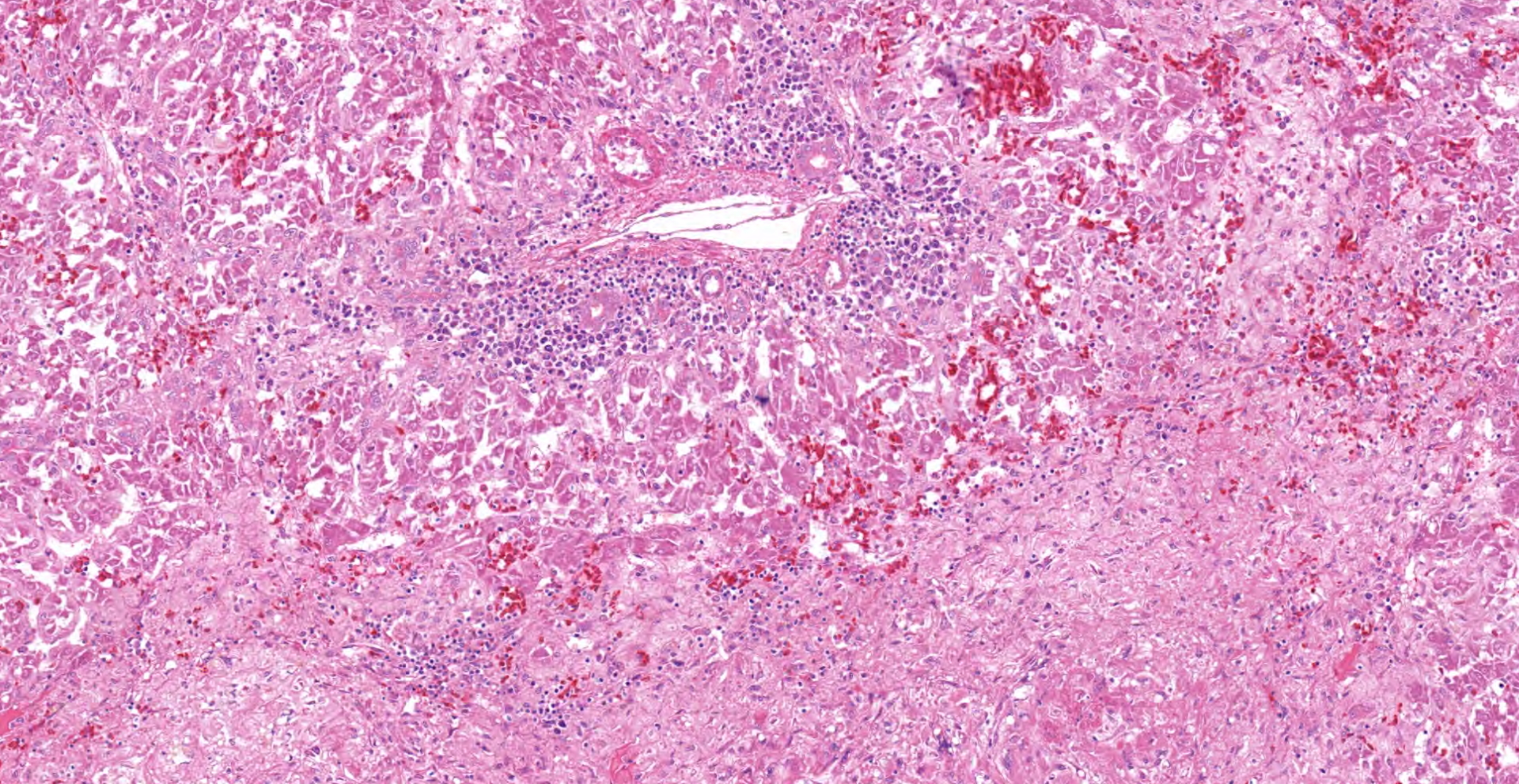

In the section of liver, coalescing foci and tracts of lytic necrosis are associated with variable hemorrhage and influx of leukocytes. Necrotic tissue is bordered by edematous fibrous stroma and diffusely infiltrated by lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages with patchy accumulation of homogeneous eosinophilic material. Some portal venules have fibrinoid change with variable infiltration by mononuclear leukocytes. Viable hepatic lobules are disorganized with disrupted plates and individualization of hepatocytes. Spaces of Disse are widened by plasma or fibrin. Portal tracts are infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells. The hepatic capsule is edematous with fibroplasia and hypertrophied mesothelial cells.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Multifocal necrotizing and hemorrhagic hepatitis

Contributor's Comment:

Avian hepatitis E virus (HEV) is considered the major cause of hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome (HS) in chickens, which was first described in Canada in 1991 and subsequently in the US.1,3 The conditions known as big liver and spleen disease (BLS) in Australia (reported in 1980) and hepatic rupture hemorrhage syndrome (HRHS) in China are attributed to variants of the same virus.5 The virus, isolated from US cases in 2001, commonly results in subclinical infection, but can also cause slight increases in mortality from 30-72 weeks of age in broiler-breeders and layers as well as decreased egg production.6 Oral inoculation of 60-week-old specific-pathogen-free chickens with avian HEV resulted in infection and lesions of HS in about one-fourth of the infected chickens.3

Gross lesions typically include splenomegaly?though not as consistently as in BLS?along with a large, pale, and friable liver that has multifocal hemorrhages, subcapsular hematomas, and blood clots adherent to the hepatic capsule.2,3 Histologically, coalescing foci of hemorrhagic necrosis are associated with lymphocytic hepatitis. Inflammation is most severe around portal venules, described as a lymphocytic periphlebitis; variable number of plasma cells, macrophages, and heterophils accompany the lymphocytes. Segmental lymphocytic portal phlebitis is accompanied by accumulation of homogeneous eosinophilic material that resembles amyloid, but generally is not congophilic.2,3

Diagnosis is based on typical history (slight increase in mortality in broiler-breeders or layers), lesions, and?because it is difficult to isolate from cell culture?identification of the virus by avian HEV-specific nested RT-PCR.5 Transmission is mainly by the fecal-oral route, thus more common in cage-free than in caged chickens.4 Biosecurity and prevention of fecal-oral transmission is recommended for control because no commercial vaccine is available.5 Co-infections, e.g., with avian leucosis virus or Marek's disease virus, are common in clinical cases.5,6

Avian hepatitis E virus has four major genotypes and is classified in the Orthohepevirus B genus along with mammalian hepatitis E viruses.5 However, although interspecies transmission occurs between chickens and other birds (turkeys experimentally and wild birds), avian hepatitis E viral transmission to pigs, rhesus monkeys, or humans has not been documented, so it is generally not considered to have a public health risk.5

Contributing Institution:

Purdue University

Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory: http://www.addl.purdue.edu/

Department of Comparative Pathobiology: https://vet.purdue.edu/cpb/

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, random, multifocal to coalescing, chronic, severe, with lymphocytic cholangiohepatitis.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise summary of Avian hepatitis E virus (HEV), the etiologic agent of big liver and spleen disease, hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome, and hepatic rupture hemorrhage syndrome in chickens.

Avian HEV is a non-enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus composed of an approximately 6.6 kb genome with three open reading frames (ORFs) and non-coding regions at the 5' and 3' ends. The assembly and release of viral particles is mediated by a non-structural polyprotein encoded by ORF1, which is composed of methyltransferase, papain-like protease, viral helicase, and RNA dependent RNA polymerase. ORF2 encodes the capsid proteins, which serve as the major antigentic epitopes associated with immune responses and play multiple roles in both viral replication and pathogenesis. ORF3 encodes a phosphoprotein that associates with the host cell's cytoskeleton.8

As noted by the contributor, broiler breeder hens and layers between 30-72 weeks of age are most commonly affected by avian HEV. The disease is typically subclinical with a mortality rate of only 0.3-1.0% in affected flocks. However, these subclinical infections likely contribute toward avian HEV's widespread distribution since the virus is readily shed by infected animals into the environment, resulting in contamination of feed, drinking water, and bedding.7,8 Following ingestion, the virus undergoes primary replication within the gastrointestinal tract, with detectable virus within 5 days post infection (dpi) in the colon and cecum under experimental conditions, as well as within the ileum (7dpi), duodenum and jejunum (20dpi), and cecal tonsils (35dpi). Based on mammalian HEV infections, the virus then travels to the liver as a secondary site of replication where it is subsequently released into bile produced by infected hepatocytes. The contaminated bile is then expressed as part of the normal digestive process and eventually excreted into the environment.7

Despite HEV's low mortality rate and typically subclinical infections, it is a disease of economic significance. For example, in Australia nearly 50% of flocks are affected, resulting in an annual loss of eight eggs per hen in affected flocks, leading to the loss of 2.8 million Australian dollars per year. Within the United States, one survey of 1276 chickens from 76 flocks in five states found 71% of flocks to be seropositive. In addition, the study found seropositivity increased based on age, with only 17% of chickens less than 18 weeks of age were seropositive, while the 36% of adult chickens had circulating avian HEV antibodies.7

Although the host range of Avian HEV is limited to chickens under field conditions, experimental infection has successfully been demonstrated in turkeys (Melagris gallopavo), which not only seroconvert but also develop viremia and shed the virus in feces. Attempts to experimentally infect both mice and rhesus macaques have been unsuccessful.7

References:

1. Aziz T, Barnes HJ. Avian hepatitis-e-virus infection in chickens ? Part 1. Poultry World. 2012;9. https://www.poultryworld.net/Broilers/Health/2012/9/Avian-hepatitis-E-virus-infection-in-chickens--Part-1-WP010890W/

2. Aziz T, Barnes HJ. Avian hepatitis-e-virus infection in chickens ? Part 2. Poultry World. 2013;1. https://www.poultryworld.net/Health/Articles/2013/1/Avian-hepatitis-E-virus-infection-in-chickens---Part-2-1137296W/

3. Billam P, Huang FF, Sun ZF, et al. Systematic pathogenesis and replication of avian hepatitis E virus in specific-pathogen-free adult chickens [published correction appears in J Virol. 2006 Jul;80(13):6721]. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3429-3437.

4. Liu B, Sun Y, Chen Y, et al. Effect of housing arrangement on fecal-oral transmission of avian hepatitis e virus in chicken flocks. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13:282.

5. Sun P, Lin S, He S, Zhou EM, Zhao Q. Avian Hepatitis E Virus: With the Trend of Genotypes and Host Expansion. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1696.

6. Sun Y, Lu Q, Zhang J, et al. Co-infection with avian hepatitis e virus and avian leucosis virus subgroup J as the cause of an outbreak of hepatitis and liver hemorrhagic syndromes in a brown layer chicken flock in China. Poultry Sci. 2020;99:1287-1296.

7. Yugo DM, Hauck R, Shivaprasad HL, Meng XJ. Hepatitis Virus Infections in Poultry. Avian Dis. 2016;60(3):576-588.

8. Zhang Y, Zhao H, Chi Z, et al. Isolation, identification and genome analysis of an avian hepatitis E virus from white-feathered broilers in China. Poult Sci. 2022;101(3):101633.