Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 15

16 January 2019

CASE IV: AFIP 16 (JPC 4102152).

Signalment: 3-year-old, neutered male, mixed breed dog.

History: A 3-year-old mixed breed, neutered male dog had a 6-month history of glossitis with firm raised plaques affecting the proximal third of the tongue. The animal initially responded to prednisone and antibiotic therapy, but improvement stagnated, and two surgical debridements were needed to remove plant material and accelerate the healing process. On follow-up consultation, the dog presented a 95% improvement with only a small focal residual lesion still present.

Gross Pathology: A 3-year-old male dog presented with lesions on the tongue. The rostral third of the tongue had multifocal to coalescing raised, firm and irregular plaques, painful to the touch.

Laboratory results: N/A

Microscopic Description:

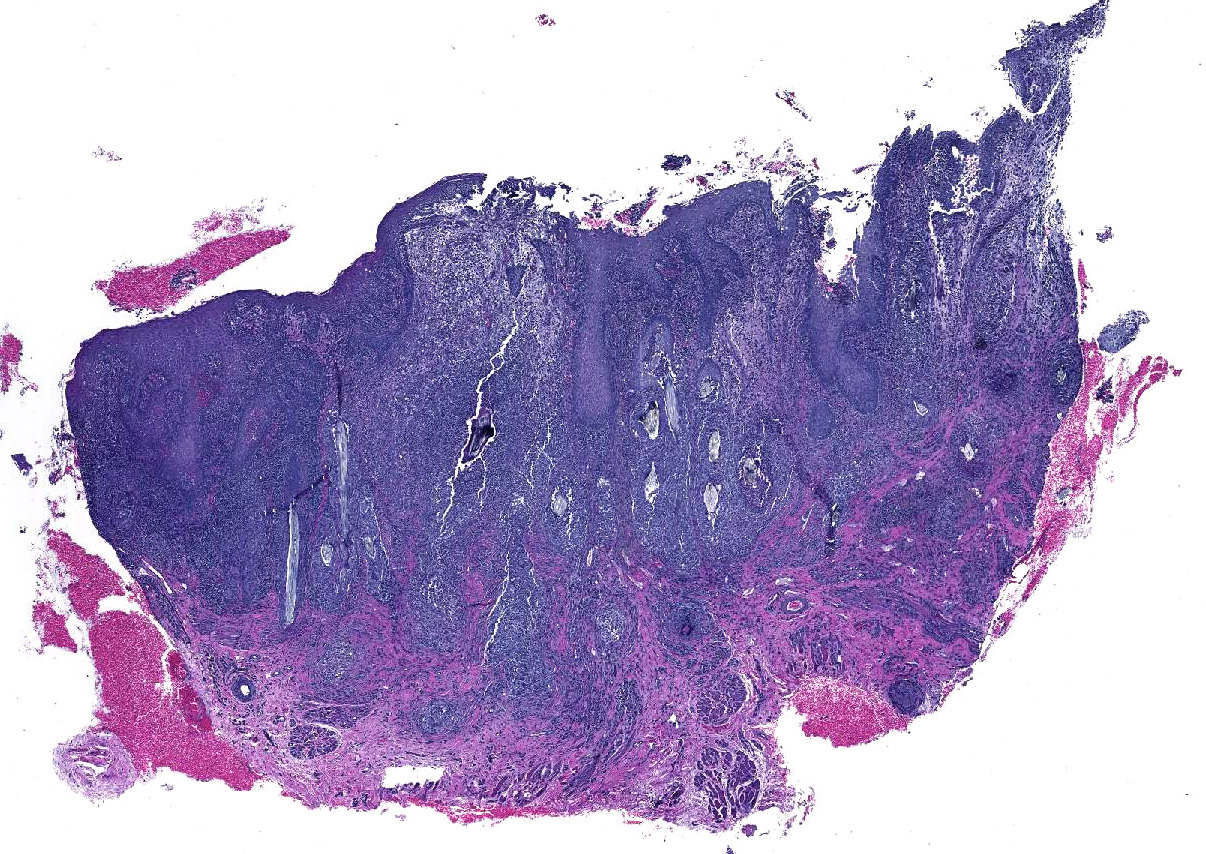

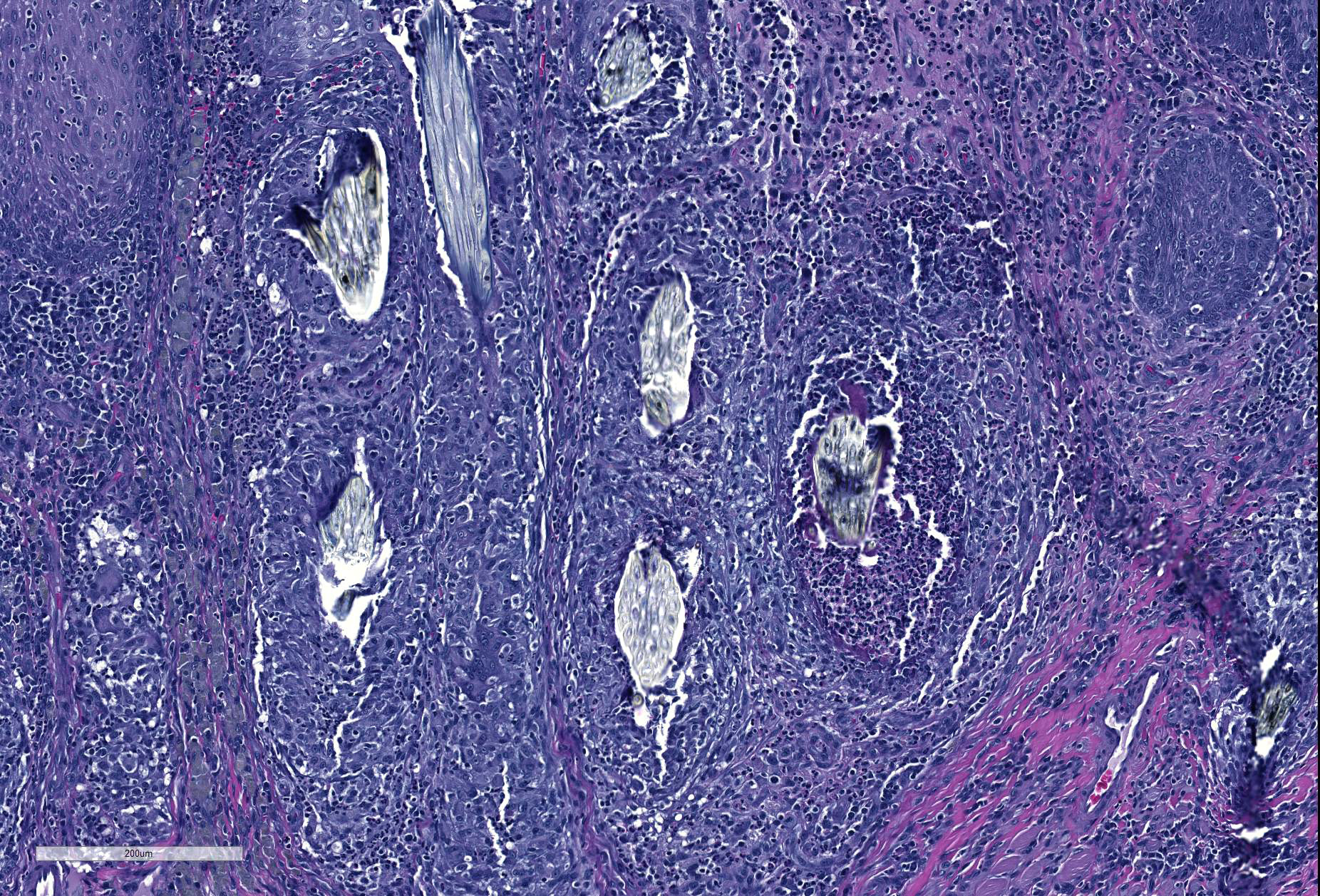

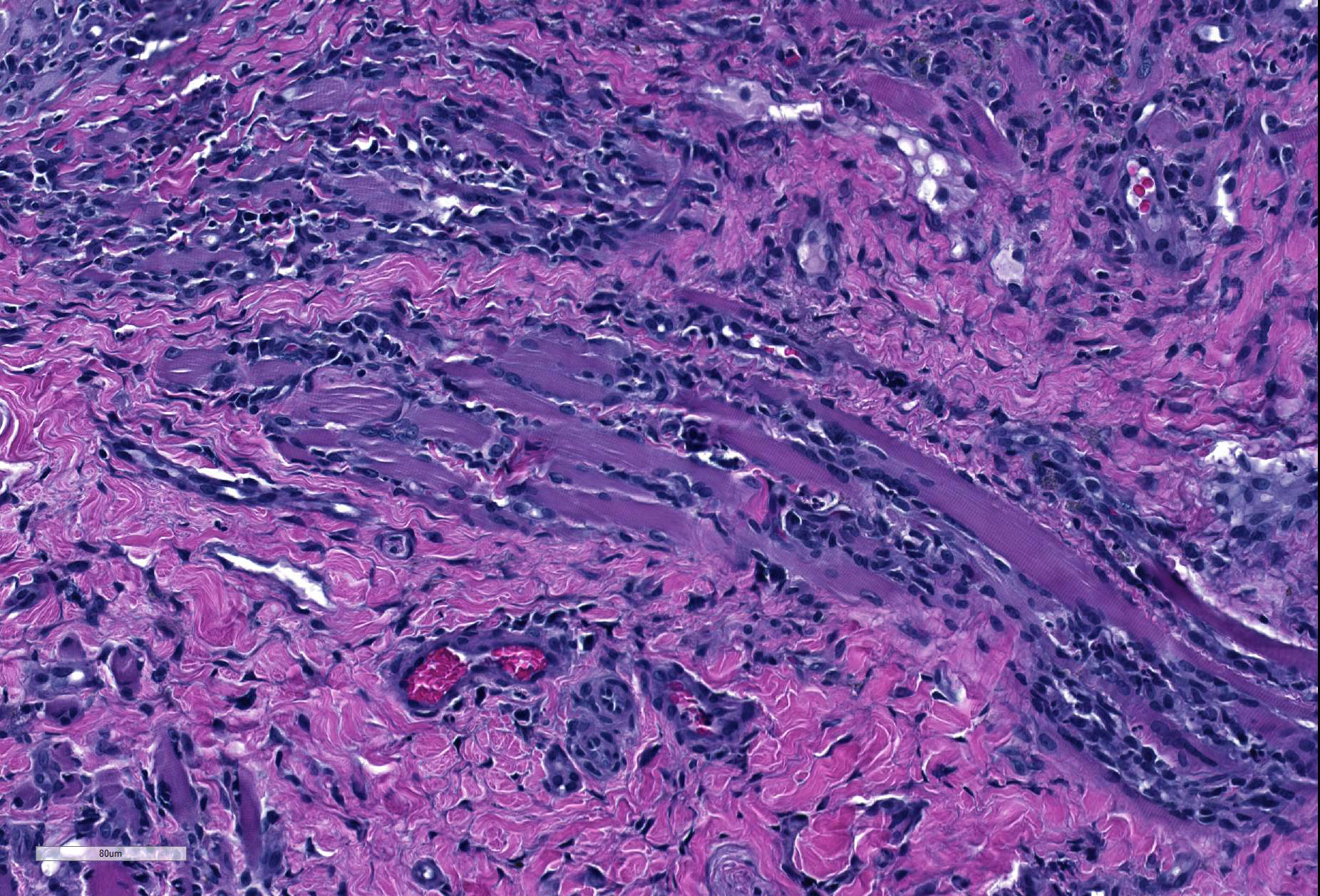

Tissue sections of mucous membrane consistent with tongue. Expanding and elevating the submucosa, and infiltrating deeper layers of muscular bundles are severe, multifocal to coalescing, nodular infiltrates of epithelioid macrophages, degenerate neutrophils, and eosinophils surrounding fragments of embedded plant material. Many of the plant fragments have visible spiny projections. The submucosa is multifocally severely edematous with dilated lymphatics and scattered areas of hemorrhage. The surface epithelium is irregularly thickened with scattered intra-corneal pustules, areas of ulceration and is occasionally covered by a 5 to 10 layers of a thick serocellular crust.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Tongue: Severe, multifocal to coalescing, chronic, pyogranulomatous and eosinophilic ulcerative glossitis associated with foreign plant material.

Contributor’s Comment: Lingual lesions are relatively infrequent in dogs; they mostly consist of neoplasms and glossitis associated with trauma or infections. This case is an example of the latter, a severe granulomatous inflammation associated with foreign plant material. The extension of the lesion combined with spiny projections of the plant is highly suggestive of burdock glossitis (“burr-tongue”)1. Arctium lappa L., also known as greater burdock, was introduced to the United States and can be currently found throughout the country, except for a few Southeastern and Southwestern states.5

Burdock blooms during the summer (July and August). As a result, there is an increase in the incidence of “burr glossitis” particularly in long haired dogs; plant structures tend to accumulate and stick to the coat around the mouth.The flower has a pappus with numerous exposed bristles with sharp hooks that firmly stick to clothes and animal coats.1

Although Arctium sp. are the predominant etiology for this type of lesion, other plants such as cactus glochids and Setaria sp. have also been associated with burr-tongue in multiple species.4 Different structures of the plant such as burrs, fibers or quills can perforate the tongue and lodge itself in deeper layers of connective or muscular tissue, eliciting an inflammatory response. Oral lesions most often occur on the tip and edges of the tongue, anterior parts of the upper lip and gum, and may also affect the philtrum.

Clinical signs vary according to the severity of inflammation and the number of lodged bristles, but they include salivation, anorexia, drooling with mild oral discomfort, halitosis, sensitive mouth, and polydipsia.4

Differential diagnosis in these cases include the ingestion of caustic chemicals leading to ulcerative lesions, and ulcerated oral neoplasms such as squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma, and granular cell tumor.

Contributing Institution:

Oregon State University Diagnostic Laboratory

http://vetmed.oregonstate.edu/diagnostic

JPC Diagnosis: Tongue: Glossitis, pyogranulomatous and ulcerative, multifocal to coalescing, chronic, with granulation tissue, and abundant plant material.

JPC Comment: The veterinary literature actually contains few reports of plant-induced stomatitis, and the human literature apparently contains none at all (at least based on a Pubmed search.)

“Burr tongue” is a condition which is apparently well-known to practitioners in areas in which Arctium sp. grows widely, and is likely a concomitant lesion in animals presented for other complaints.4 Clinical signs of careful and slow eating and drinking may not be noticed by the owner. Volcanic ulcers with necrotic centers on the tip and edges of the tongue may require deep curetting or excision to remove the plant scales and the granulation tissue that they are embedded in, and this procedure may need to be repeated several times.4

Setaria sp., another common genus of plants referred to as “foxtails” or “bristlegrass”, is well known for causing ulcerative stomatitis in horses when unwittingly incorporated into forage hay. Veterinarians may be consulted for “outbreaks” of stomatitis that may mimic vesicular diseases of the horse, such as vesicular stomatitis, but careful history often reveals the introduction of a new hay source.5 Setaria stomatitis results in varying degrees of gingivitis, ranging from mild periodontal swelling to marked ulceration, as well as that of labial mucosa in contact with the affected gingiva. Similar, but more severe lesions throughout the oral cavity have also been identified in horse and experimentally in cattle fed a Satu variant of triticale hay in Australia.2 Affected animals became totally anorexic and displayed submandibular edema due to the severity of ulcerative lesions throughout the pharynx. A single case report of migrating awns from barley clusters was reported to cause lingual arteritis, meningoencephalitis, and uveitis in a two-year-old heifer.

Histologically, the lesions of this and other plant awns, such as glochids from prickly pear cacti and foxtail awns from Setaria sp. have been reported to be identical both with regard to the characteristic chronic and pyogranulomatous inflammation as well as the appearance of the plant material itself. While the barbs on the bristles of these plants may be oriented either anteriorly or posteriorly, this bit of identifying information is generally useful only in examining the plants themselves under a dissecting microscope and not in examining tissue histologically.

References:

- Georgi, M. E., Harper, P., Hyypio, P. A., Pritchard, D. K., & Scherline, E. D. Pappus bristles: the cause of burdock stomatitis in dogs.The Cornell veterinarian, 1982;72(1), 43-48.

- McCosker, JE, Keenan DM. Ulcerative stomatitis in horses and cattle caused by triticale hay. Austr Vet J 1983; 60:259.

- Sorden SD, Radostits OM. Lingual arteritis, multifocal meningoencephalitis and uvieitis induced by barley spikelet clustes in a two-year-old heifer. Can Vet J 1996; 37:227-229.

- Thivierge, G., 1973. Granular stomatitis in dogs due to Burdock.The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 14(4), p.96.

- Turnquist, SE, Ostlund EN, Kreegar JM, Turk JR. Foxtail-induced ulcerative stomatitis outbreak in a Missouri stable. J Vet Diagn Invest 2001: 13-238-240.

- United States Department of Agriculture: (USDA) http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ARLA3