Signalment:

Gross Description:

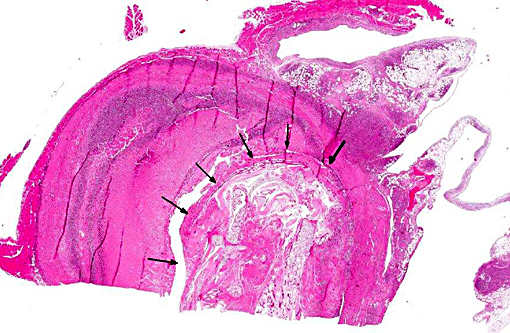

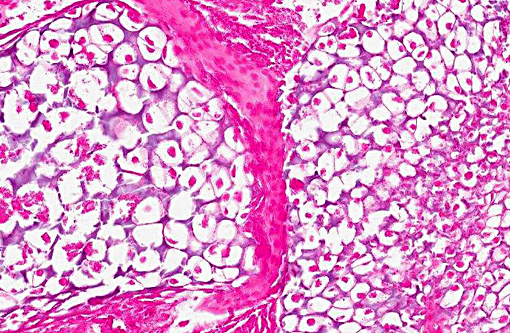

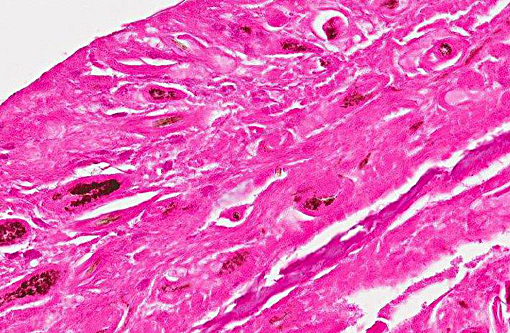

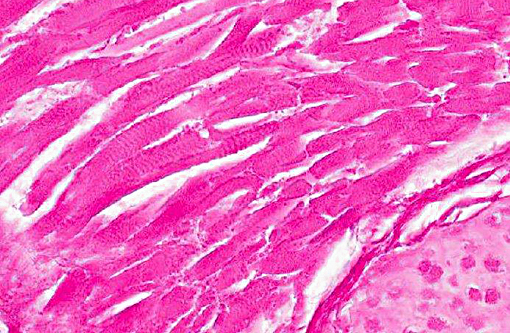

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Abdominal cavity, Serositis, severe, pyogranulomatous, chronic with necrotic skin, musculature, cartilage and bone; findings consistent with abdominal pregnancy.

Myositis, pancreatitis, steatitis, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, lymphoplasmacytic, chronic.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

A distinction is made between primary and secondary ectopic pregnancy. In cases of primary ectopic pregnancy the zygote directly adheres to maternal tissue other than the uterus. Primary ectopic pregnancies in humans can be categorized into three subgroups.(1)

Ovarian pregnancy (graviditas avarice): In these cases, the embryo develops in direct contact with the ovary. Only human cases have been reported so far.Â

Tube pregnancy (graviditas tub aria): It is the most frequently occurring primary ectopic pregnancy in humans that is often associated with severe intraabdominal hemorrhages. No cases have been reported in animals other than non-human primates.

Abdominal pregnancy (graviditas abdominal is): A true primary abdominal pregnancy has not been described in animals. One reason might be the fact that due to gastrointestinal movements in animals, the implantation of the zygote is inhibited. In contrast, due to the upright body position in humans, the zygote has a better chance to connect with extra-uterine maternal tissue caused by the relatively small pelvic cavity and the lesser influence of gastrointestinal movements in this area.Â

In secondary abdominal pregnancy the embryo or fetus starts to develop within the uterus. Subsequently, it is dislocated to the abdominal cavity and attached to extra-uterine maternal tissue with connection to maternal blood vessels. Secondary abdominal pregnancies are reported in all domestic animals with a declining frequency: cattle, rabbit, sheep, dog, pig, cat, goat and horse.(1,2,5) In mice, abdominal pregnancy has also been induced experimentally with living fetuses placed into the abdominal cavity.(4)

Secondary abdominal pregnancy is often caused by trauma or spontaneous uterine rupture. This process is called internal birth (parts interns). In most cases, when the abdominal pregnancy is recognized the cause of the uterine rupture cannot be identified anymore. Spontaneous uterine ruptures are often a consequence of uterine torsions or other pathological uterine conditions. Directly after dislocation of the embryo or fetus into the abdominal cavity the uterus contracts and uterine contractions stop immediately. The fate of the abdominal embryo or fetus depends on the ability to connect to maternal tissue and to ensure the connection to maternal blood vessels to guarantee nutritional supply. In cases with intact amniotic membranes the probability for an embryonic or fetal survival increases.(1,2,5)

In the maternal abdominal cavity, the embryo or fetus is initially recognized as a foreign body and within hours a circumscribed, serofibrinous inflammation starts which develops to an adhesive peritoneal reaction without involvement of infectious agents. Often a capsule is formed. In cases with neoplacentation, the placental fragments lose their species-specific properties and transform into irregularly formed islets of diffuse placental connections. Neoplacentations can occur in various abdominal organs. Neoplacentations within the mesentery or the great omentum normally do not cause clinical signs of the mother. Neoplacentations in other organs may be associated with severe clinical signs of the mother due to disturbances of normal organ function.Â

During the whole duration of abdominal pregnancy the embryo or fetus can die due to nutritional failure. If this happens the embryo or fetus will undergo mummification or maceration and may induce a reactive inflammatory reaction. This may lead to abscess formation and fistulation through the abdominal wall or inflammatory involvement of several abdominal organs.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Another important question pertaining to this case is regarding the age of the fetus. Many deliberated as to its gestational age, and subsequently, how long prior to necropsy it had died. Ectopic pregnancies occur most commonly in the fallopian tube in people, and fetal development occurs as usual until, in some instances, its size outgrows the tissues ability to expand. This may cause a rupture 6-8 weeks into gestation of a fallopian tube pregnancy.(3) With an average gestation of just 20 days in mice, the history of mating 14 days prior to necropsy indicates this fetus may have been close to term. Whether the majority of this development occurred within the uterus prior to a rupture or largely took place while attached to the abdominal wall as observed in these slides remains a point of speculation.Â

References:

1. Corpa JM. Ectopic pregnancy in animals and humans. Reproduction. 2006;131:631-640.Â

2. De Kruif. Von den Fr+�-+chten ausgehende St+�-�rungen der Gravidit+�-�t. In: Richter J, G+�-�tze R eds. Tiergeburtshilfe. 4th ed. Berlin, Germany: Parey; 1993:146-147.

3. Ellenson LH, Pirog EC. The female genital tract. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:1036.

4. Hreshchyshyn MM, Hreshchyshyn RO. Experimentally induced abdominal pregnancy in mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;89:829-832.

5. Weisbroth SH, Scher S. Spontaneous multiple abdominal pregnancies in a multiparous NCS mouse. Lab Anim Care. 1969;19:528-530.