WSC 2022-2023

Conference 13

Case 4

Signalment:

3-year-old, intact male, Syria Hamster, Mesocricetus auratus, Mesocricetus

History:

It was reported by the owner that the patient had been progressively ailing over a three-month period and that a small mass had been present on his right eye for at least 6 months. On October 14th, 2020, he was found to be cold, trembling, and weak for several hours, but aware of his surroundings. The slight trembling of his hind limbs continued to the next day. Later, the abdominal organs became progressively enlarged and visible through his skin. Four months later the patient became lethargic and began open mouth breathing. The left eye became proptosed and unable to be closed. Patient progressed to teeth grinding and lateral recumbency, with closed mouth, but labored breathing. Patient was euthanized shortly after.

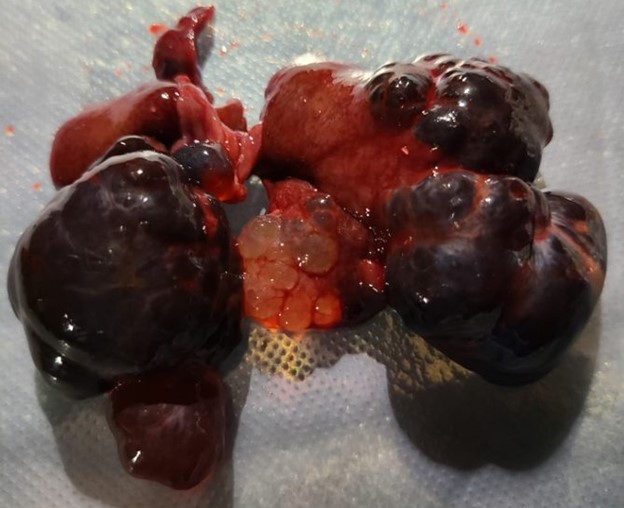

Gross Pathology:

The left lateral, left medial, and right medial liver lobes are fully to partially effaced by soft, multilobular masses that measure 1cm x 3cm x 1.5cm to 2cm x2cm x1cm. The masses are black to red, soft, fluid filled.

Laboratory Results:

No findings reported.

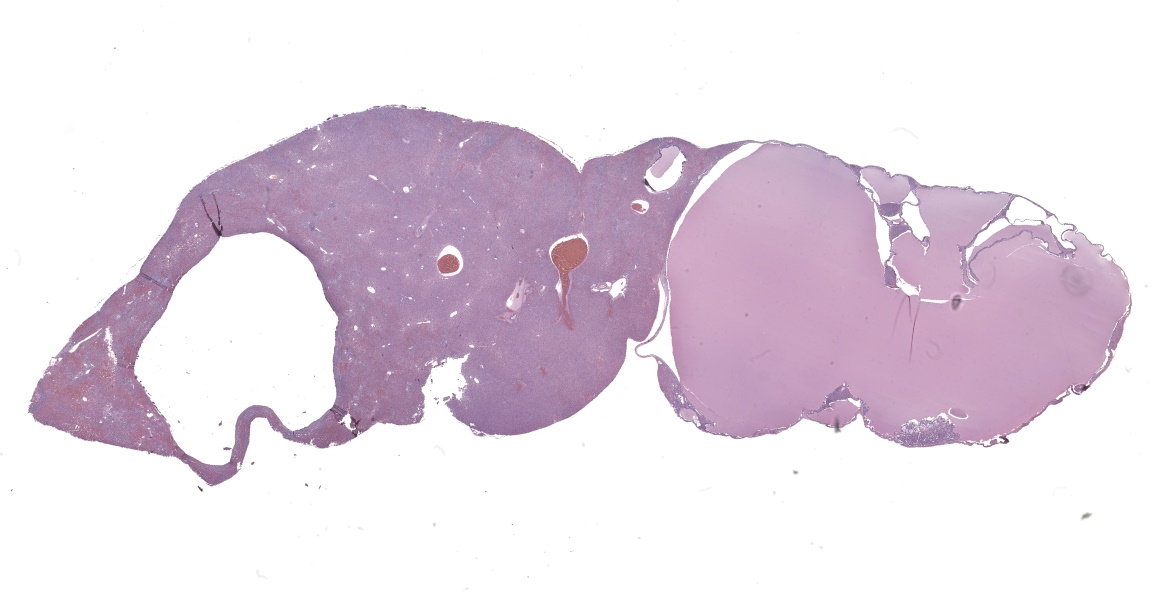

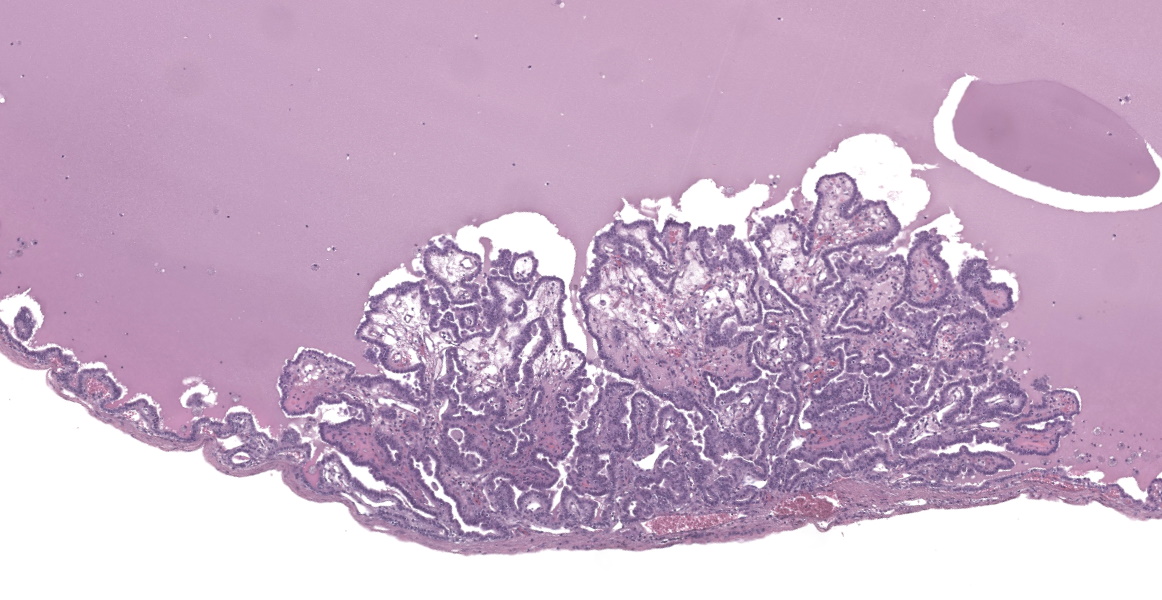

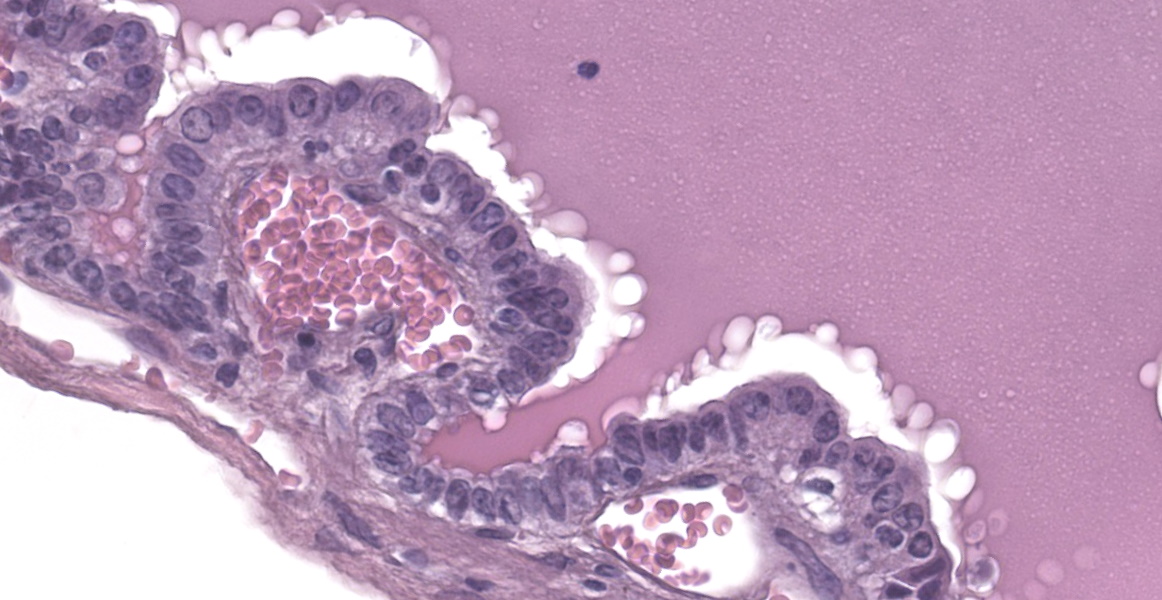

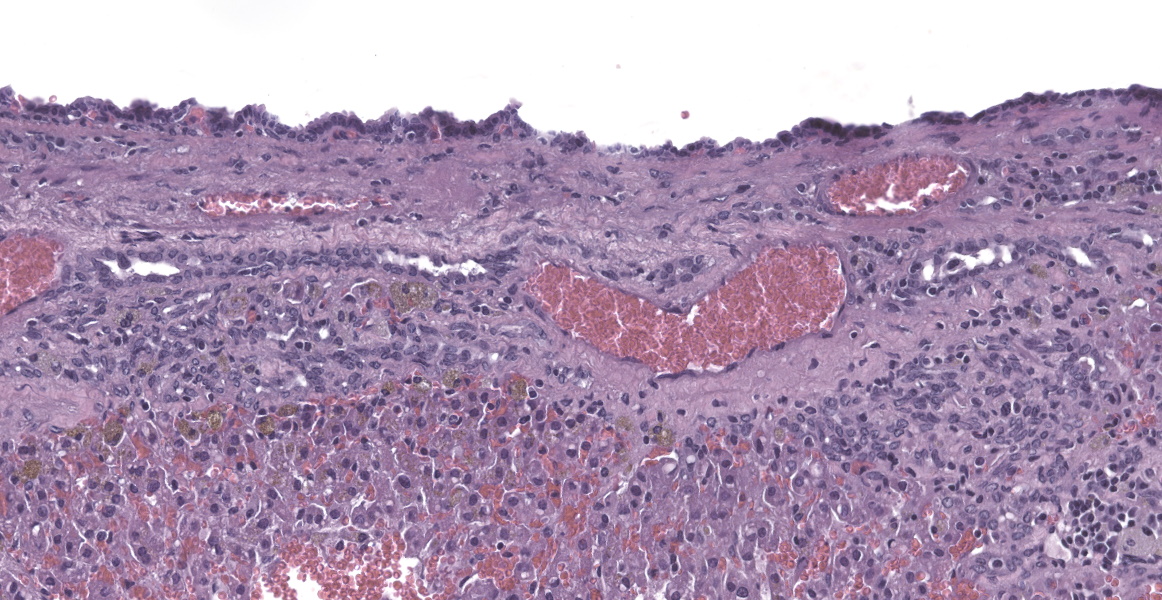

Microscopic Description:

Liver: In multifocal areas the hepatic parenchyma is replaced by large cystic structures lined primarily by a single layer of cuboidal epithelial cells; occasionally there are up to three layers of cells. The lining cells occasionally form variably sized papillae that project into the lumen of the cysts. The lumen of the cystic structures contains an amphophilic, homogenous, vesiculated fluid substance. Portal regions frequently are infiltrated with mild to moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Most portal regions have mild to marked bile duct hyperplasia. In areas of severe bile duct hyperplasia, the surrounding hepatocellular parenchyma contains multifocal areas of hemorrhage with distortion of hepatic cord architecture and individual hepatocyte necrosis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Multifocal hepatic cysts (polycystic liver disease)

Multifocal moderate to marked bile duct hyperplasia and lymphoplasmacytic periportal hepatitis with multifocal hemorrhage and individual cell necrosis

Contributor’s Comment:

This Syrian hamster had many of the common findings in aged hamsters including severe glomerulonephropathy, an atrial thrombus, and marked hepatic disease.14 Although hepatic cysts are very common in older hamsters, they are thought to be the result of disconnected biliary structures present during hepatic development.3 Ductal structures become disconnected from the biliary tree through loss or defects in genes signaling.5 Affected animals remain asymptomatic until cyst growth initiates in adulthood.

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is very well characterized in humans and is subdivided into three distinct entities.3 The diseases are categorized by both the genetic mechanism and the gross and histological appearance of the lesions. The first is Von Meyenburg complexes (VMC) also called biliary hamartoma or hepatic cystic hamartoma.9 These lesions have characteristic small, nonhereditary nodular cystic lesions which histologically appear as discrete fibrotic areas with small, irregular bile ducts. The second is isolated polycystic liver disease (autosomal dominant PLD) with presence of innumerable hepatic cysts and autosomal dominant heredity. The final category of PLD is polycystic kidney disease (PKD) where cysts are present in both the kidneys and liver.19

Polycystic liver disease in hamsters is characterized by multiple hepatic cysts that eventually lead to the replacement of normal liver parenchyma.10,13 The etiology of PLD in hamsters has not been completely elucidated but much research has been done to understand PLD in isolation and PLD in association with polycystic kidney disease (PKD) in humans. Non PKD associated PLD is the result of mutations in several genes including LRP5, PRKCSH, and SEC63 which are in charge of making the proteins sec-63 and hepatocystin.16 These gene are also responsible for fluid transportation and epithelial cell growth. In polycystic liver disease associated with PKD, renal complications such as renal failure are more common.16 PKD1 and PKD 2 are the genes are responsible for making polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 and mutation leads to dysregulation of fluid secretion and abnormal growth, ultimately leading to cyst formation.4

Hepatic cysts associated with PLD must be differentiated from cysts that might be seen in association with hepatic neoplasms in which cysts may develop such as cholangiocarcinoma or cystadenoma. Syrian hamsters, in general, have a low prevalence of spontaneous tumors of the liver.8 Kondo et al examination of 15 Syrian hamsters found a single hepatic hemangioma.8 The epithelial cell papillary projections, hepatic degeneration, necrosis, and leukocyte infiltration seen in this case is not typically seen in PLD but are common findings in neoplastic disease of the liver.16 True cysts are usually multiple and lined by a single layer of epithelium, whereas tumors can be single or multiple, uni or bilateral, and may have a complex arboriform pattern. The lack of cellular pleomorphism, stromal invasion, and mitotic figures suggest a non-malignant process. Cysts and cyst-like structures that develop from parasites, abscesses, or hematomas must also be differentiated from PLD.1,15

Contributing Institution:

Tuskegee University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology, https://www.tuskegee.edu/programs-courses/colleges-schools/cvm

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Biliary cysts, multiple, with bridging ductular reaction and focal intraductal biliary papillary hyperplasia.

JPC Comment:

In hamsters, this relatively common incidental lesion observed in older animals may be accompanied by cysts in the epididymis, seminal vesicles, pancreas, and endometrium.15 Infrequently, there may be clinically detectable hepatomegaly and ascites with straw colored fluid. The surrounding hepatic parenchyma typically shows pressure atrophy, necrosis, and congestion with possible hemorrhage.18 Adjacent hepatocytes may demonstrate vacuolar change and there may be biliary ductular reaction within periportal regions.18

Conference participants discussed the presence of focal papillary projections into the cyst lumen, and considered the possibility that ductal plate anomalies may evolve into a neoplastic process (biliary cystadenoma), or a neoplasm may spontaneously occur in the same tissue. Dr. Cullen explained that because the genetic mechanism for polycystic liver disease has not been elucidated in this species, the specific pathogenesis creating papillary projections cannot be distinguished. Participants decided that the inflammation in the section is a secondary reactive hepatitis and elected not to include it in the morphologic diagnosis.

Polycystic liver has been documented in many species, including dogs, cats, pigs, mice, several deer species, chamois, llamas, alpacas, and various fish species.6,7,12,18,20 Spontaneous polycystic liver has recently been documented in seven K14-LacZ transgenic mice; cysts were lined with cuboidal epithelium that was occasionally ciliated.12 Affected males also had seminiferous tubular degeneration and a spermatogenesis, while two of the three females had ovarian cysts; affected mice appeared to be infertile.12

In veterinary medicine, cystic liver lesions may also be a component of adult or juvenile polycystic diseases.2 Adult polycystic kidney disease, which has a higher prevalence in bull terriers and Persian cats, is a slowly progressive disease which may include cysts in other organs, such as the liver.2 In humans, the disease is linked to autosomal dominant mutations in PKD1 and 2, and in dogs and cats, it has been linked to PKD1.2,17 The mutation causes modification of the polycystin-1 protein in the primary cilia, which forms the centriole during mitosis, serves as a mechanoreceptor, and plays a role in fluid transport. Ciliary dysfunction appears to decrease fluid absorption during cyst development.17 This disease may feature cysts in the liver and pancreas as well as hepatic fibrosis.2 An autosomal recessive form of polycystic kidney disease in humans has been associated with a mutation causing dysfunction of fibrocystin, another component of the cilia.2 This has been documented in West Highland white and Cairn terriers and some breeds of sheep and may also feature cysts in the liver.2

References:

- Brown, Cynthia, and Thomas M. Donnelly. “Disease Problems of Small Rodents.” Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents. 2012: 354–372.

- Cianciolo RE, Mohr FC. Urinary System. In: Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. Elsevier: 2016; 395-396.

- Cnossen, W.R., Drenth, J.P. Polycystic liver disease: an overview of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis.2014; 9, 69.

- Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. Elsevier: 2016; 265-266.

- Drenth JP, Chrispijn M, Bergmann C: Congenital fibrocystic liver diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010; 24:573–584.

- Foster A, Duff P, Boufana B, Acaster E, Schock A. Adult polycystic liver disease in alpacas. Vet Rec. 2013; 172(25):666-667.

- Glaswischnig W, Bago Z. Polycystic Liver Disease in Senile Chamois. J Wildl Disease. 2010; 46(2):669-672.

- Kondo H, Onuma M, Shibuya H, Sato T. Spontaneous Tumors in Domestic Hamsters. Veterinary Pathology. 2008; 45(5):674-680.

- Lev-Toaff AS, Bach AM, Wechsler RJ, Hilpert PM, GatalicaZ, RubinR: The radiologic and pathologic spectrum of biliary hamartomas. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1995; 165(2): 309-313

- Lewis J. Pathology of Fibropolycystic Liver Diseases. Clinical Liver Disease. 2021; 238-243

- Longergan GJ, Rice RR, Suarez ES. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2000; 20:837-855.

- Lovaglio J, Artwohl JE, Ward CJ, Diekwisch GH, Ito Y, Fortman JD. Case Study: Polycystic Livers in a Transgenic Mouse Line. Comp Med. 2014; 64(2):115-120.

- Miao Jinxin, Chard Louisa S., Wang Zhimin, Wang Yaohe Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study on Infectious Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019; 10:2329--3224

- Miedel, Emily L, Hankenson FC. “Biology and Diseases of Hamsters.” Laboratory Animal Medicine. 2015: 209–245.

- Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. Iowa State University Press, 2016: 191–196.

- Perugorria MJ, Masyuk TV, Marin JJ, et al. Polycystic liver diseases: Advanced insights into the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 11:750-761.

- Schirrer L, Marin-Garcia PJ, Llobat L. Feline Polycystic Kidney Disease: An Update. Vet Sci. 2021; 8(11): 269-279.

- Somvanshi R, Iyer PKR, Biswas JC, Koul GL. Polycystic Liver Disease in Golden Hamsters. J Comp Path. 1987; 97:615-618.

- Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007; 369:1287–1301.

- Watanabe TTN, Chaigneau FRC, Adaska JM, Doncel-Diaz B, Uzal FA. Polycystic liver in two adult llamas. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019; 31(2): 280-283.