CASE III: 18-7537 (JPC 4135935)

Signalment:

3 year old spayed female, Boxer cross dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

The dog lost the ability to bark twelve months prior to being referred to the Western College of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Medical Centre for further investigation of a previously identified laryngeal or tracheal mass. On physical examination the dog was BAR but a marked abdominal component was observed with inspiration. The dog was eating and drinking normally without any episodes of vomiting or regurgitation. The dog had experienced respiratory dyspnea with excitement and episodes of tonic-clonic seizures during these episodes. Survey cervical radiographs revealed a poorly circumscribed, large, homogenous soft tissue opacity that deviated the larynx and trachea ventrolaterally and to the right. During anesthetic induction for advanced imaging studies (CT and MRI) two large masses could be observed, one tonsillar and one laryngeal. The caliber of the trachea was narrowed and required the placement of a small endotracheal tube. Due to respiratory complications the advanced imaging studies could not be completed. The owner elected euthanasia when informed of the advanced nature of the mass and the need for a temporary or permanent tracheostomy tube. The owner consented to incisional biopsy of the laryngeal mass following euthanasia. Imprint cytology was performed and the biopsy was submitted for histopathologic examination. A complete post mortem examination was declined.

Gross Pathology:

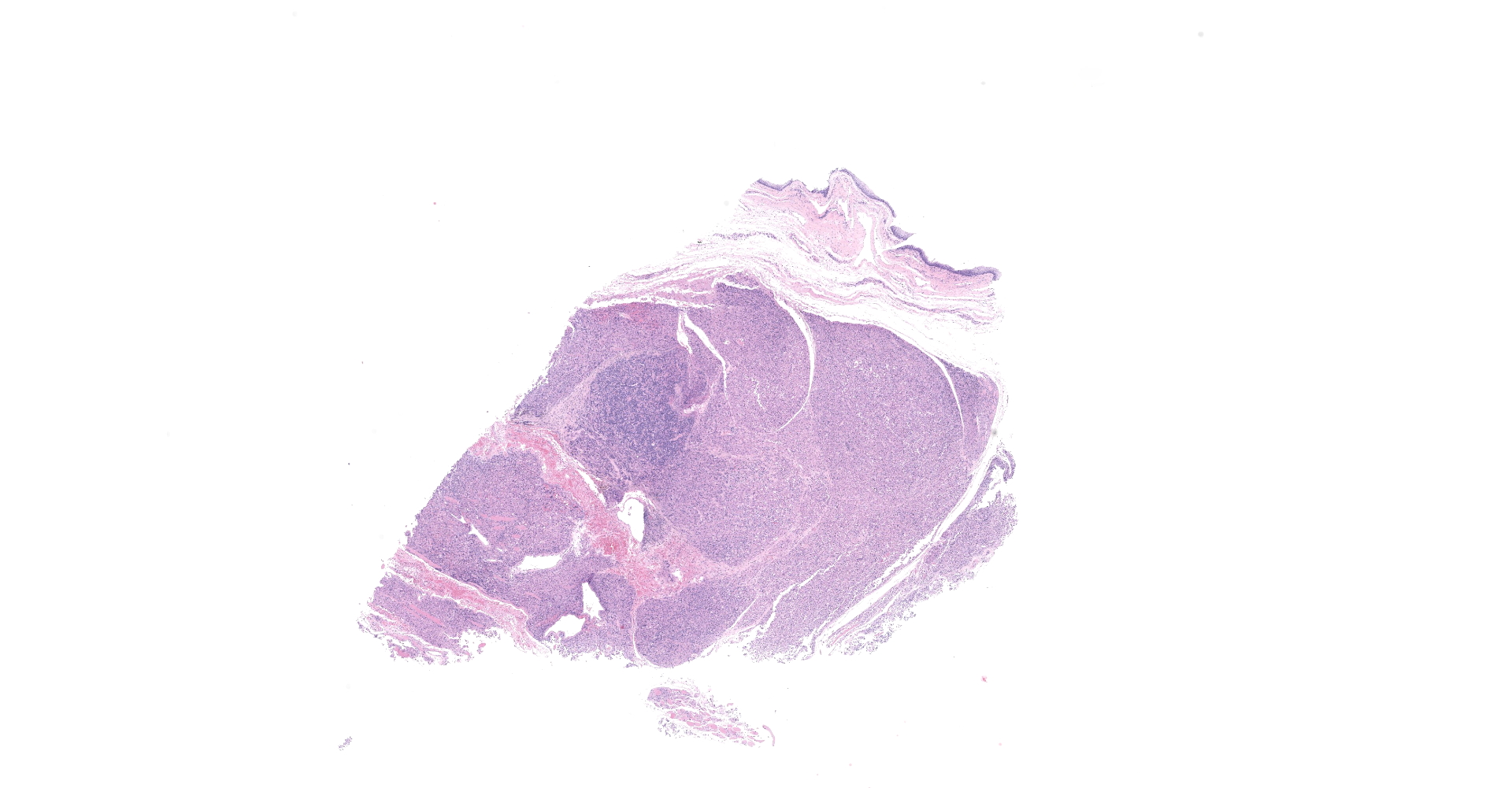

Received a 0.7 x 0.5 cm brown, soft to firm mass. Four sections were submitted for routine processing.

Laboratory results:

No laboratory findings reported.

Microscopic Description:

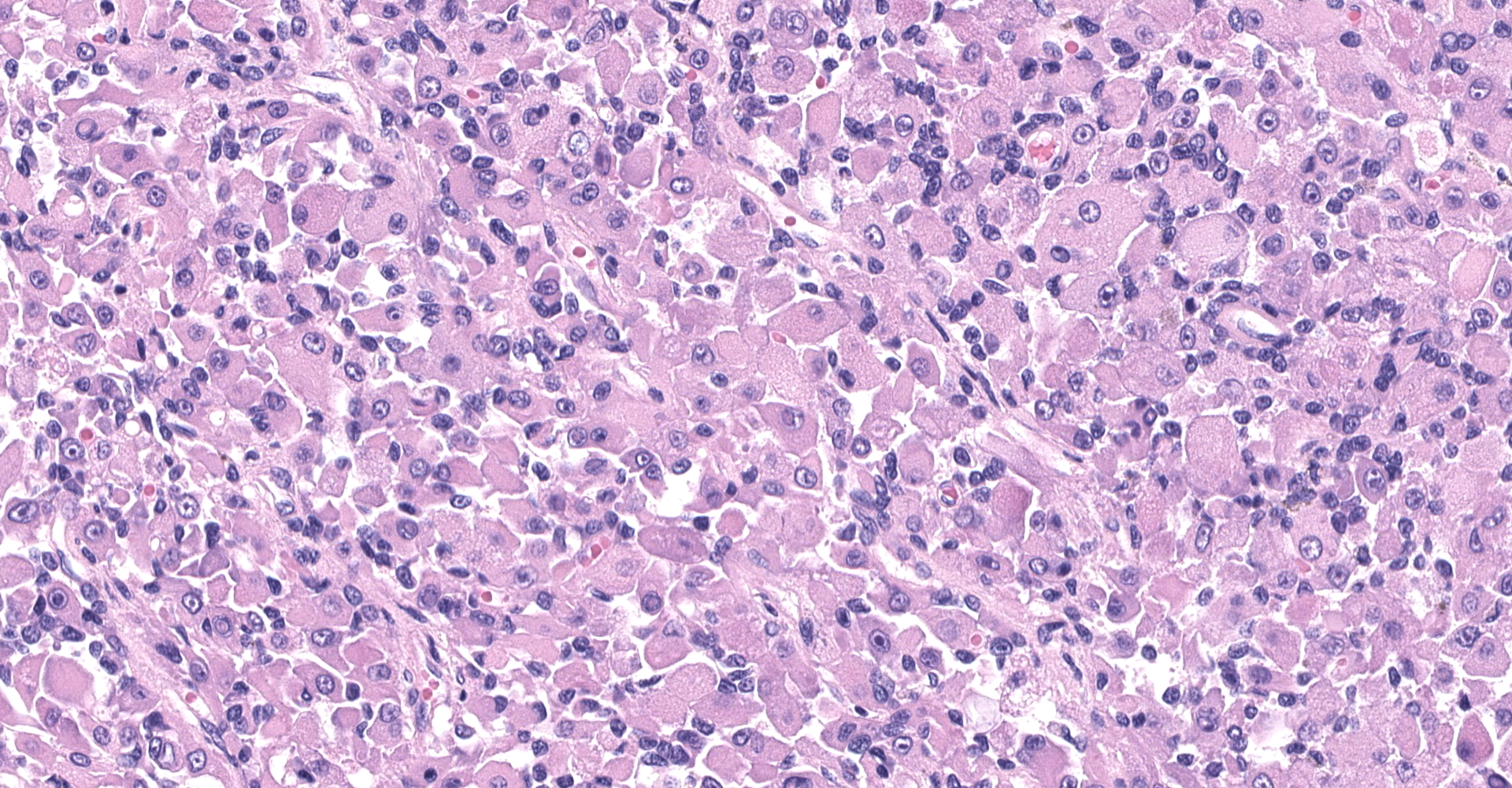

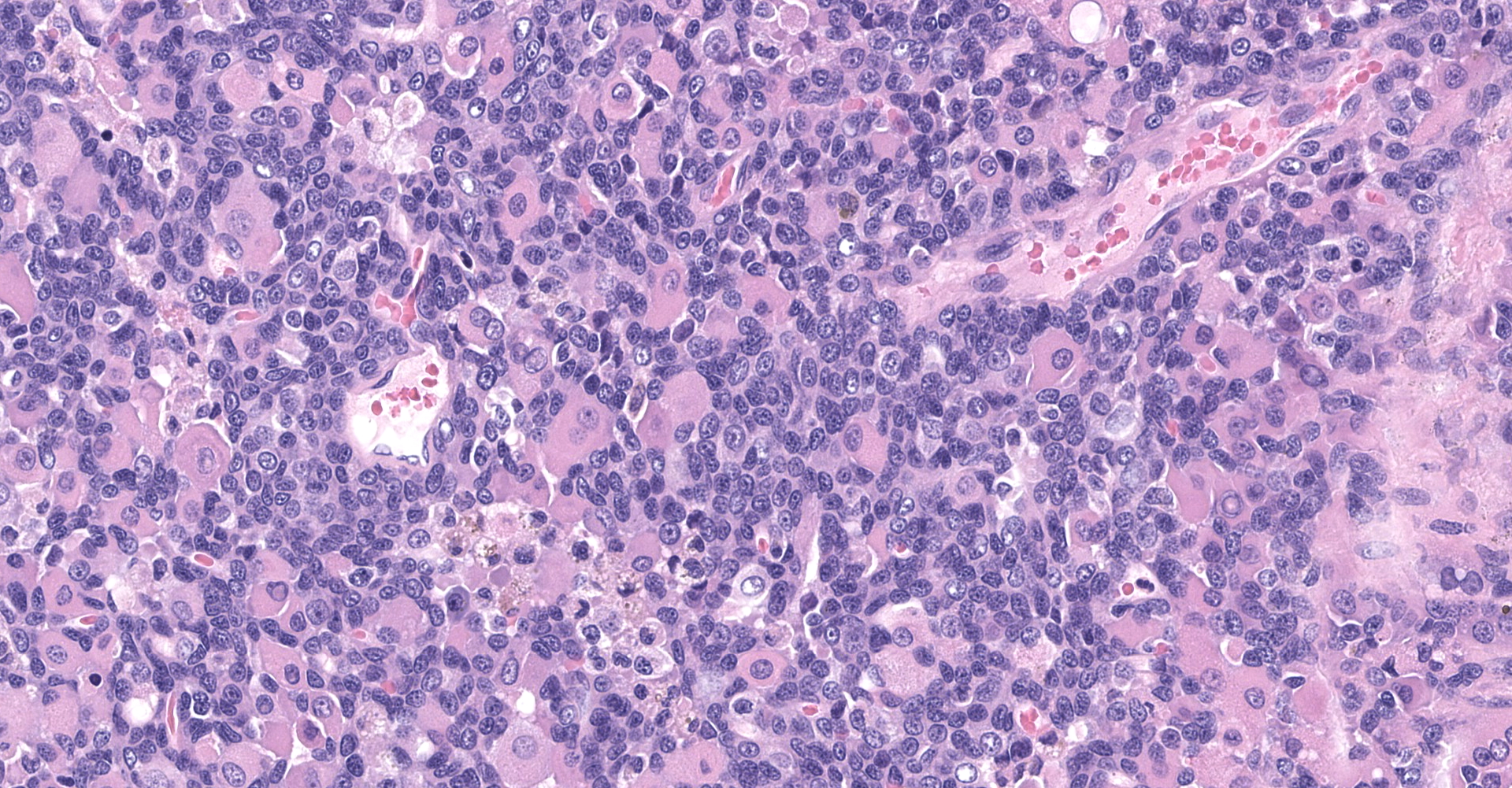

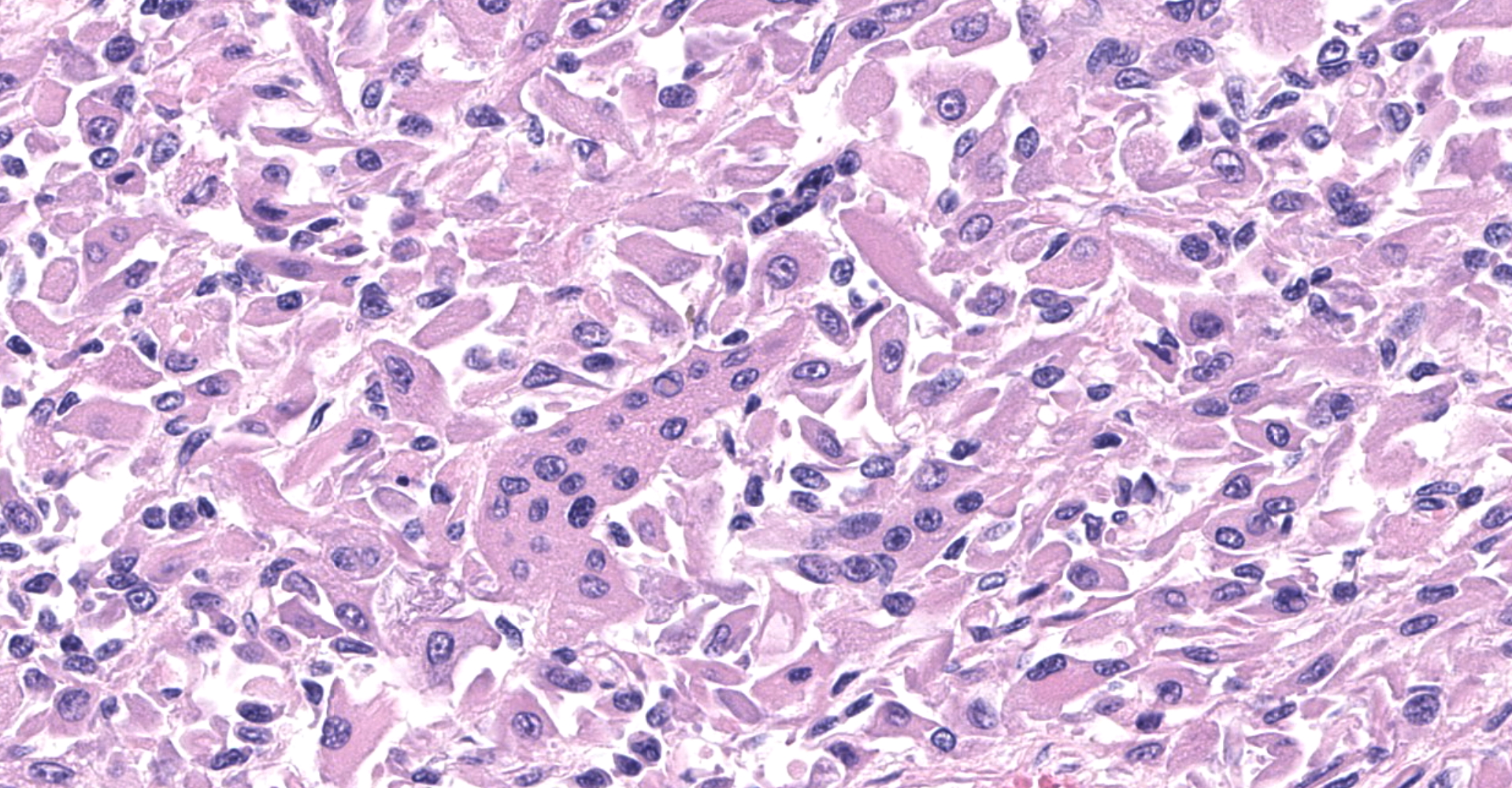

The sections are partially covered by oral mucosa and in the submucosa there are lobules that are separated by thick bands of fibrovascular connective tissue stroma. Lobules comprise sheets of round to polyhedral to elongate cells with distinct to indistinct cell borders and a low to moderate nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. The nucleus is centric, round with a coarsely stippled chromatin pattern and single, small round nucleolus. The cytoplasm is moderate to high, bright pink and appears smooth to finely granular. Pink intranuclear inclusion bodies are frequent. Anisokaryosis and anisocytosis are moderate. Multinucleate forms (up to 6 nuclei) are seen. Mitoses are rare (2 in 10 random 40x objective fields). Some of the elongate forms appear to have fine cytoplasmic cross striations and in some the nuclei are almost linearly arrayed (strap cells). There are also focal aggregates of smaller round cells with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and hyperchromatic nuclei. The tumor cells are present in the stroma supporting bundles of skeletal muscle myocytes. There are foci of hemorrhage in the mass. Hemosiderophages are scattered throughout the arrangements of tumor cells.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Tumor of skeletal muscle origin ? laryngeal rhabdomyosarcoma most likely.

Contributor's Comment:

The histologic findings in the biopsy from the laryngeal mass coupled with the clinical findings, and immunohistochemical stains are most consistent with a laryngeal rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS). RMSs are malignant neoplasms of striated muscle, which originate from muscle progenitor mesenchymal cells or from myocytes undergoing neoplastic transformation.1,2 The majority of RMSs in dogs have occurred in tissues that do not normally contain striated muscle, such as the pharynx, gingiva, urethra, trachea, larynx and the jawbone.1 In veterinary medicine RMSs can be classified into subtypes based on histologic characteristics: embryonal, alveolar, botryoid (aka: botryoid embryonal) and pleomorphic RMS. The clinical relevance of this tumor subtyping has not been established in veterinary medicine.1 The variation in phenotype, age of onset and cellular morphology makes the diagnosis and classification of RMS difficult. The diagnostic features of skeletal muscle differentiation are not always evident on light microscopic examination and immunohistochemistry and ultrastructural examination are often needed to confirm the diagnosis.1

Canine laryngeal rhabdomyoma-sarcoma is considered a rare, distinct clinical entity in dogs, being locally invasive but rarely metastatic.1,6 Complete excision is often difficult due to local invasion and recurrence of these tumors often lead to euthanasia. Although most are histologically benign, they may cause death or result in euthanasia due to laryngeal obstruction ? as in this case. Affected dogs typically present with dysphonia, aphonia, stridor and dyspnea. Due to the limited number of cases age, sex and site predilection have not been recognized.

Canine laryngeal rhabdomyoma and rhabdomyosarcoma have been diagnosed as laryngeal oncocytoma in the past. Laryngeal rhabdomyomas-sarcomas can be distinguished from laryngeal oncocytomas by positive staining by myoglobin and desmin or by the ultrastructural presence of myofibers in addition to intracytoplasmic glycogen (PAS+ and diastase-sensitive) and numerous mitochondria.1,2

The use of immunohistochemical stains for desmin, α-actins, myogenin and MyoD1 and ultrastructural identification of sarcomeric structures can be used to determine if relatively undifferentiated tumors could be RMS.

Contributing Institution:

Prairie Diagnostic Services (PDS) and Department of Veterinary Pathology

Western College of Veterinary Medicine

52 Campus Drive, University of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5B4, Canada

www.pdsinc.ca www.usask.ca/wcvm/vetpath

JPC Diagnosis:

Larynx: Rhabdomyoma.

JPC Comment:

In humans, rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common soft tissue tumor of adults and children. Unfortunately histologic features that clearly distinguish between rhabdomyoma and rhabdomyosarcoma have not been well documented in veterinary literature.3 As previously noted by the contributor, the World Health Organization Classification categorizes human RMS as embryonal (includes the botryoid subtype), alveolar, pleomorphic, or spindle/cell sclerosing. The prognosis varies according to category and subtype, with botryoid subtypes being associated with a more favorable outcome in comparison to the poor prognosis associated with alveolar RMS. Although the same classification scheme is applied to canine RMS, the prognostic significance of category and subtype are undetermined.5

Diagnosis of RMS based solely on histologic evaluation can present a challenge, as RMS cells can vary widely in morphology, presenting as round, or well-differentiated or undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. As noted by the contributor, immunohistochemical stains for MyoD1 and myogenin are commonly used in human medicine to distinguish RMS from other mesenchymal or embryonic tumors, which is in contrast to less specific markers typically used in veterinary pathology, including muscle-specific actin, desmin, and vimentin to diagnose RMS, which can potentially result in inaccurate diagnosis.5

Myogenin and MyoD1 are both transcriptional regulatory proteins that stimulate early stages of myogenesis.4, 5 Both proteins are present in fetal skeletal muscle cells and regenerating muscle cells, demonstrating nuclear immunoreactivity; normal adult skeletal muscle is negative. Given these transcriptional regulatory proteins are expressed early in skeletal muscle differentiation, expression of MyoD1 and myogenin has been demonstrated to be the greatest in less differentiated rhabdomyosarcomas in humans.5

A recently published study evaluating the immunohistochemical reactivity of canine RMS found myogenin and MyoD1 to be useful for diagnosing RMS in conjunction with histopathologic characteristics and desmin immunoreactivity. Of the 13 cases diagnosed as RMS in the study, 100% were MyoD1 positive and five were positive for myogenin.5

Although cost prohibitive, transmission electron microscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of RMS. Key features include poorly developed cytoplasmic myofilament tangles associated with numerous polyribosomes and short electron-dense bands or plaques.5

In this case, approximately 10% and 5% of neoplastic cells demonstrate strong nuclear immunoreactivity for MyoD1 and myogenin, respectively. There is diffuse, weak to moderate cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for muscle specific actin, whereas 30% of neoplastic cells have weak to strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for desmin. Neoplastic cells are diffusely negative for smooth muscle actin and AE1/AE3 (pancytokeratin), inconsistent for leiomyosarcoma and oncocytoma, respectively. These findings, combined with the histomorphologic features, are consistent with a skeletal muscle neoplasm.

There was spirited discussion amongst conference participants in regard to the diagnosis of canine laryngeal rhabdomyoma versus rhabdomyosarcoma in this case. Unfortunately histologic features that clearly distinguish between the two have not been well documented. Features that should raise the possibility of malignant biological behavior include a high percentage of undifferentiated cells, invasive growth, and a high mitotic count.3 The majority of participants preferred the diagnosis of rhabdomyoma based on lack of invasiveness at the near margin (although the lateral and deep margins could not be assessed) and low mitotic count. However, a significant minority preferred the diagnosis of "skeletal muscle neoplasm" due to significant overlap of histomorphologic features shared between the two entities.

References:

1. Caserto BG. A comprehensive review of canine and human rhabdomyosarcoma with emphasis on classification and pathogenesis. Vet Pathol, 2013; 55(5):806-826.

2. Madewell B, Lund J, Munn R, and Pino M. Canine laryngeal rhabdomyosarcoma; an immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Jpn J Vet Sci, 1988, 50(5):1079-1084.

3. Roccabianca P, Schulman FY, Avallone G, Foster RA, Scruggs JL, Dittmer K, Kiupel M. Syncytial striated muscle tumors. In: Kiupel M, ed. Surgical Pathology of Tumors of Domestic Animals Volume 3: Tumors of Soft Tissue. 3rd ed. Gurnee, IL: Davis-Thompson Foundation; 2020:220-231.

4. Thompson LDR. Immunohistochemistry of head and neck lesions. In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. 5th ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:283-288.

5. Tuohy JL, Byer BJ, Royer S, et al. Evaluation of Myogenin and MyoD1 as Immunohistochemical Markers of Canine Rhabdomyosarcoma. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(3):516-526.

6. Yamate J, Murai F, Izawa T, Akiyoshi H, Shimizu J, Ohashi F and Kuwamura M. A rhabdomyosarcoma arising in the larynx of a dog. J Toxicol. Pathol, 2001, 24:179-182.