Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 8

October 25th, 2017

CASE I: 11111437 (JPC 4019838).

Signalment: 10-year-old, gelding, Thoroughbred, Equus caballus, equine.

History: Horse presented to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital with a two month history of anorexia, weight loss and multiple oral ulcers. He was treated by the referring veterinarian with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs and immune stimulants (dosages and types not provided by owner). On ultrasound, multiple pulmonary masses were noted distributed throughout all lung fields. Differential diagnoses included infection vs. neoplasia. Owner opted for euthanasia over further diagnostics and treatment. Patient was euthanized and submitted for necropsy.

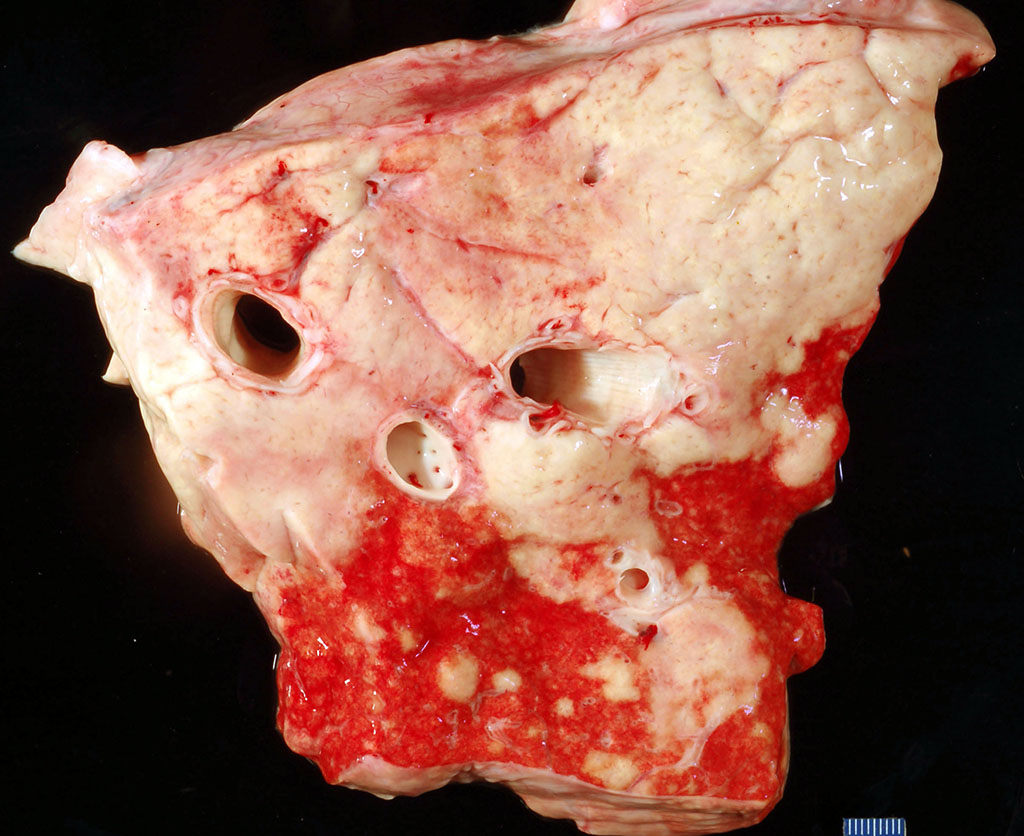

Gross Pathology: The lungs are firm throughout, with prominent pleural vessels on the pleura and sub-pleura. Approximately 80% of the lung tissue is tan-to-white and matte; these regions are large and irregular. The remaining 20% of the lung tissue has multifocal, coalescing lesions, ranging from 1-5mm in diameter, also tan-to-white and matte. Yellow-brown purulent material is occasionally present in the bronchi on the left side. Bronchial lymph nodes are diffusely, severely enlarged and on cut surface are homogeneous and tan.

Laboratory results: None performed.

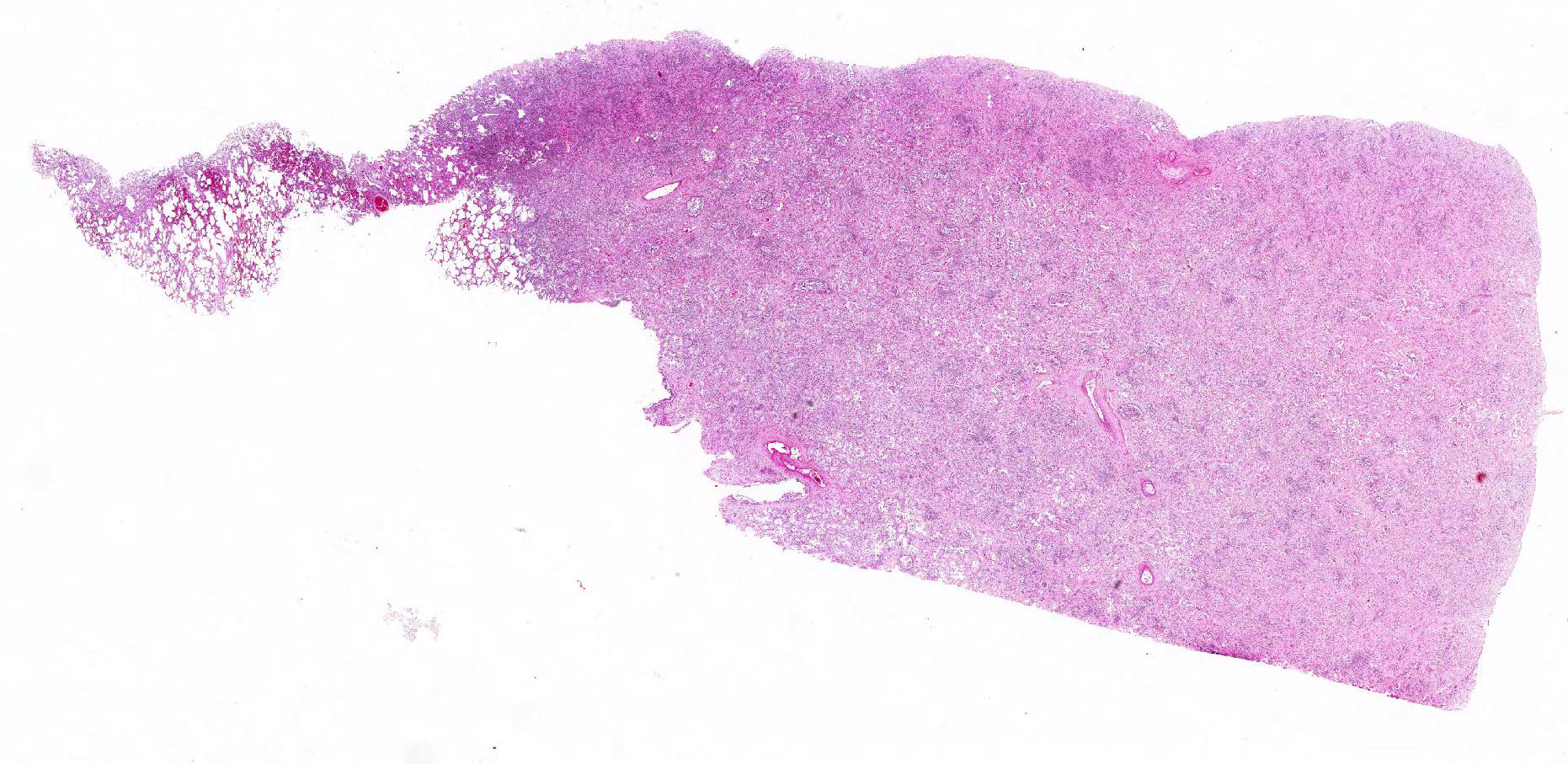

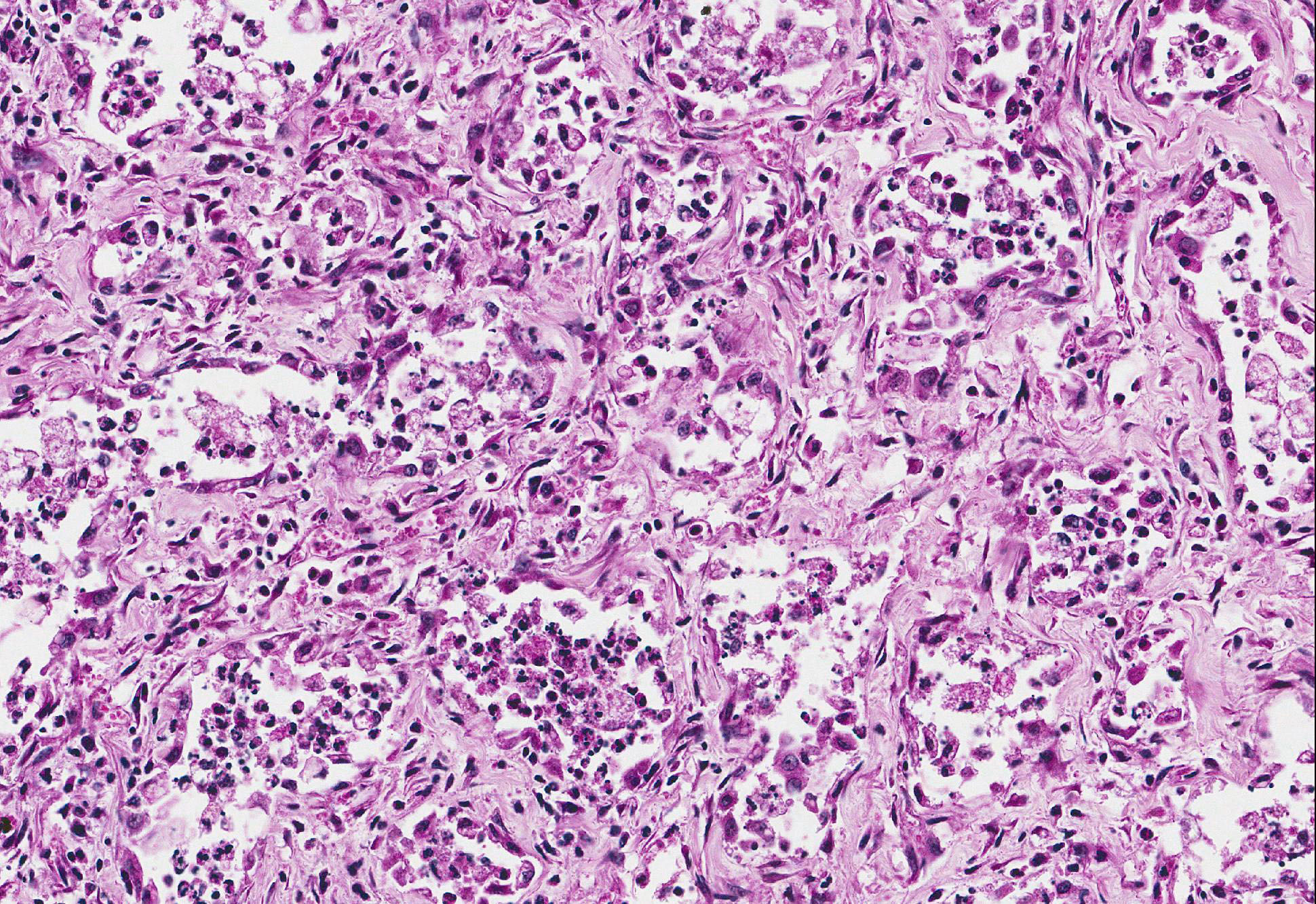

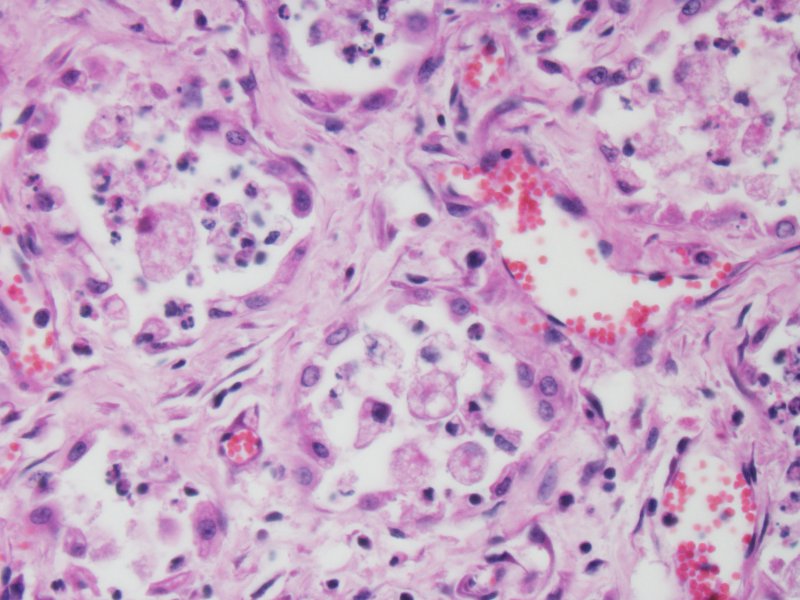

Microscopic Description: Lung: Within severely affected areas of the lung, alveolar septa are widely expanded due to dense mature fibrous connective tissue. There is moderate to marked pneumocyte hyperplasia that partially to completely line alveoli, and most lumens contain foamy macrophages interspersed with cell debris and other inflammatory cells including neutrophils, both viable and degenerate. Bronchiolar epithelium is hyperplastic and lumens contain debris, neutrophils, mucus, and foamy macrophages. Multifocally, within more normal areas, foamy macrophages are present within alveoli and bronchioles. Interalveolar septa are often mildly expanded due to fibrous connective tissue. Hemosiderin-laden macrophages are numerous within alveolar lumens and within septal walls.

The normal architecture of the bronchial lymph node is effaced by thick bands of fibrous connective tissue throughout the node. The cortex and medulla are not distinct, sinusoids are small and cellular, and lymphocytes throughout are mainly small lymphocytes. There is moderate extension of lymphocytes through the capsule.

The spleen (sections not provided) exhibits marked hemosiderosis of the red pulp. In white pulp, the lymphocytes are widely separated. Small lymphocytes predominate and are interspersed with a few large mononuclear cells that contain moderate cytoplasm and large round to oval, dense nuclei. Within some of these cells, there is chromatin margination and equivocal, centrally-located, viral-type inclusion body.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Multinodular, interstitial pneumonia with marked interstitial fibrosis.

Contributors Comment: The lung lesions are consistent with the equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis (EMPF) syndrome described by Williams et al. in the United States.5 The syndrome has also been observed within horses in the UK.4 This unique disease has been associated with infection by equine herpesvirus-5 (EHV-5).

Clinically, horses with multinodular pulmonary fibrosis syndrome have a mean age of 13-14 years and there is no sex or breed predilection.5 The patients present with a variable display of tachypnea, tachycardia, respiratory difficulty, cough, and anorexia and weight loss.5 Clinical pathology often shows a leukocytosis secondary to a mature neutrophilia and elevations of the acute phase inflammatory protein fibrinogen (hyperfibrinogenemia). Lymphopenia, characteristic of acute viral infection, is found in some EMPF horses.5

Grossly, there are two morphological forms of the disease.3 Most common are large, individual to coalescing nodules of fibrosis that typically leave little to no normal lung left. A less common gross presentation are individual, disseminated nodules of fibrosis separated by normal lung tissue; this presentation can be confused with a metastatic, neoplastic process, which was a clinical differential in the current case. The current case exhibited more of the common gross lesion characterized by near effacement of the lung by coalescing masses of fibrosis.

Histologically, there is marked interstitial fibrosis that can either retain the open alveolar architecture or efface it by less well organized bundles of fibrous connective tissue deposition. Retained airways are often filled with inflammatory cells. Bronchial lymph node lesions recognized by Williams et al.5 included reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. In the current case, the lymph node was partially effaced by broad sweeping bands of fibrous connective tissue that obscured the corticomedullary junction and otherwise lacked the reactive hyperplasia of the original report.

EMPF has been associated with EHV-5 infection. Intranuclear viral inclusions consistent with herpesvirus are seen primarily within macrophages located in the lesions.3 In the present case, definitive inclusion bodies were not seen in any organ; however, equivocal inclusion bodies were seen within macrophages of the spleen. The spleen otherwise had no significant microscopic lesions. Although the pathogenesis of EMPF and relationship with EHV-5 has not yet been elucidated, murine models of pulmonary fibrosis may shed some clues. When pulmonary fibrosis is induced in mice infected with MHV68 (gammaherpesvirus) virally infected mice exhibit exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis over non-infected controls.6 This observation is accompanied by increased in the production of CCL-2 and CCL-12, chemokines important for fibroblast recruitment.

JPC Diagnosis: Lung: Fibrosis, interstitial, focally extensive, severe with marked type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia and rare intranuclear intrahistiocytic viral inclusions with marked intra-alveolar inflammation, Thoroughbred (Equus caballus), equine.

Conference Comment: Conference participants discussed the extensive alveolar remodeling and the possibility that the cuboidal cells lining the airspaces were not type II pneumocytes but another cell type altogether. It was decided that type II pneumocyte hyperplasia was the most accurate option for the morphologic diagnosis because type II pneumocytes are the progenitor cells within the lung parenchyma. These cells repair damaged alveolar epithelium by covering the surface, repopulating the epithelium, secreting new basement membrane, and eventually differentiating into type I pneumocytes.1

The conference moderator (who discovered this entity) referred to a study by Marenzoni, et al. that identified Equine herpesvirus 5 (EHV-5) using bronchoalveolar lavage and biopsy specimens antemortem and then during the postmortem examination were able to use quantitative real-time PCR on several tissues to identify the EHV-5 DNA load in those tissues. They concluded that the viral load was greatest in areas of fibrosis of lung and that higher viral burden resulted in more severe lesions.2

In this case, although the contributor only identified inclusions in the spleen (not submitted), the moderator and conference attendees were able to identify several convincing intranuclear viral inclusion bodies within swollen alveolar macrophages.

One remarkable aspect of this disease is the lack of temporal heterogeneity of the lesions. There is no progression in maturity of the lesions and they all appear to have begun at the same time. The conference moderator did not have an explanation for this finding and indicated it is an interesting aspect for future investigation.

Department of Veterinary Pathobiology

Center for Veterinary Health Sciences

Oklahoma State University

Rm 250 McElroy Hall

Stillwater OK 74078 USA

References:

1. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol. 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 409, 509.

2. Marenzoni ML, Passamonti F, Lepri E, Cercone M, et al. Quantification of Equid herpesvirus 5 DNA in clinical and necropsy specimens collected from a horse with equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011; 23(4):802-806.

3. McMillan TR, Moore BB, Weinberg JB, Vannella KM, et al. Exacerbation of established pulmonary fibrosis in a murine model by gammaherpesvirus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008; 177:771-780.

4. Soare T, Leeming G, Morgan R, Papoula-Pereira R, et al. Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis in horses in the UK. Vet Rec. 2011; 169: 313-315.

5. Williams KJ, Maes R, Del Piero F, Lim A, et al. Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis: a newly recognized herpesvirus-associated fibrotic lung disease. Vet Pathol. 2007; 44: 849-862.

6. Wong DM, Belgrave RL, Williams KJ, Del Piero F, et al. Multinodular pulmonary fibrosis in five horses. J Vet Med Assoc. 2008; 232: 898-905.